Big Philanthropy and Social Justice

How does organized philanthropy respond to grassroots social action? Does a social movement change direction when big funders step in? What is the appropriate role for private foundations to play in social and political change?

Power imbalances are inherent to philanthropy. Imbalances in financial resources are obvious, but there are also imbalances in knowledge, networks, prestige, political access, narrative control, and more.

These questions and issues are as old as American foundations themselves, and as relevant today as they were decades ago. One historical episode is a particularly instructive entry into these issues: a cluster of grants the Ford Foundation made between the years 1965 and 1970.I first presented this research at the 45th annual meeting of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action in Washington, DC, in November 2016. The theme of the panel, organized by Gregory Witkowski, was “Foundations and the Civil Rights Movement: Support, Moderation or Control?” Co-panelists were Eric John Abrahamson and Maribel Morey.

Supporting “Constructive” Action

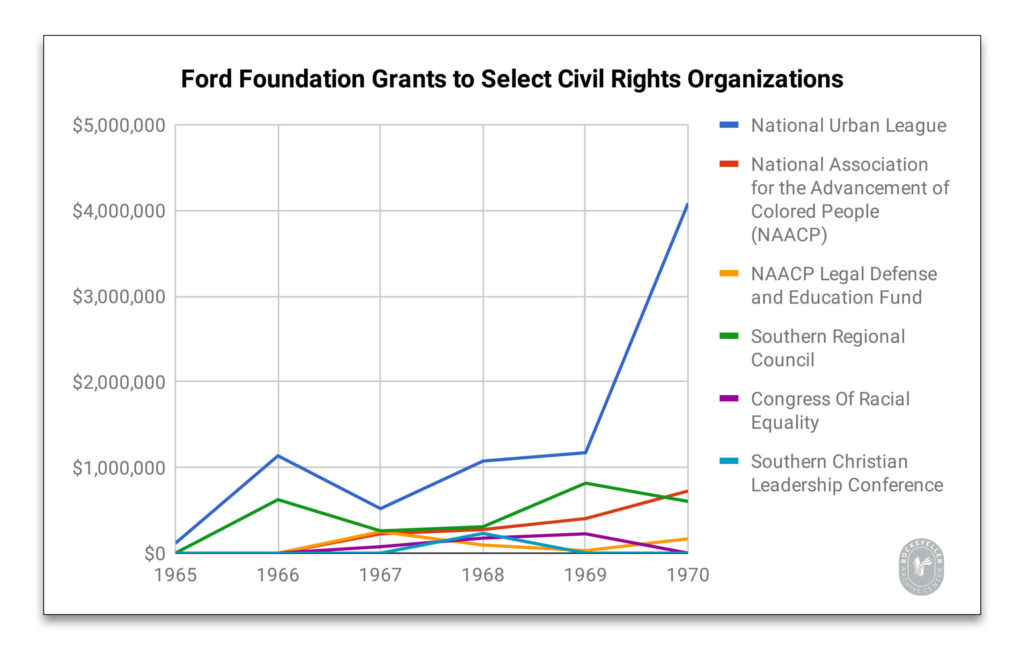

The Ford Foundation grant funding data from the late 1960s shows a preference for supporting established organizations working in the fields of education and the law. The recipients of the largest grants were the National Urban League and the NAACP. To use the words of one Ford Foundation program officer, their philanthropic approach at the time was to favor “rational” and “constructive” programs over “the man in the street.”

Although a foundation as large as Ford could — and in fact did — fund several approaches and dozens of civil rights groups at the same time, by far the largest grants went to just those two organizations.

Moderation and Movement Capture

In many ways, what happened when the Ford Foundation began funding civil rights groups in the late 1960s embodies a phenomenon scholar Megan Ming Francis calls “movement capture.”Megan Ming Francis, “The Price of Civil Rights: Black Lives, White Funding, and Movement Capture.” Law & Society Review, Volume 53, Number 1 (2019), 275-309.In her study of the NAACP and the Garland Fund in the 1920s-1940s, Francis shows how philanthropic funding shifted the NAACP’s focus from lynching to educational reform.

Writing about the Ford Foundation’s work on urban community action, school decentralization, and the arts in the 1960s and 1970s, scholar Karen Ferguson argues that “the critical national project for the American liberal establishment was to domesticate black power and its challenge to liberalism.”Karen Ferguson, Top Down. The Ford Foundation, Black Power, and the Reinvention of Racial Liberalism. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

For a variety of reasons, the Ford Foundation in the 1960s similarly favored activities in education and research. Ford shied away from direct social action. Eventually and for a variety of reasons, Ford would throw its millions to support legal strategies, shifting to litigation and the enforcement of laws already on the books.

A Vast Philanthropic Fortune

In today’s crowded philanthropic landscape, it is often easy to forget what American foundations looked like at midcentury. In the postwar years, the Ford Foundation emerged as largest philanthropic fortune the world had ever seen. Its assets were four times those of its closest rival, the Rockefeller Foundation.

By the mid-1950s, Ford had become the world’s first billion-dollar foundation. With so many eyes on the foundation, its activities made headlines. At times, Ford’s actions prompted public scrutiny, with critics on the left accusing it of wielding anti-democratic power. Critics on the right suspected Ford’s international programs of being anti-American.For an overview of the Ford Foundation at midcentury, see Francis X. Sutton, “The Ford Foundation: The Early Years.” Daedalus, Vol. 116, No. 1, Philanthropy, Patronage, Politics. (Winter, 1987), pp.41-91. On Ford’s early international programs, see Ford Foundation records, International Division, Asia and Pacific, Program Area One Files, 1951-1973, and South and Southeast Asia, Karachi and Islamabad, Pakistan, Field Office Files, 1951-1981, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Post-War Elites

Most of Ford’s work in the 1950s reflected the post-World War II liberalism in which its leaders were steeped. In fact, it was the dominant worldview many American elites shared at that time. The foundation’s leaders subscribed to the belief that science, information, and education could solve all problems, that peace would be achieved through new international organizations and cooperation, and that the world’s peoples were more interconnected than ever before. They believed in experts and expertise, locating such expertise within the realm of academic scholars, high-level political officials, and powerful business leaders.

It is worth remembering that these elite ranks were by and large filled with white, American men.

A Focus on Education

In the 1950s, Ford, like its peers the Rockefeller Foundation and Carnegie Corporation, poured vast amounts of dollars into educational institutions. Famously, a December 1955 push to liquidate Ford’s stock assets and support US private higher education came to be known as “The $500 million weekend.” New academic centers were built. Chaired professorships were created. Impactful philanthropy often meant building or overhauling a field.

But who pays the piper…

Of course, this didn’t always feel impactful from the grantee side. Frustrated by Ford’s attempt to remake the field of legal education, for example, law professor Philip Mechem in 1958 addressed the Association of American Law Schools, of which he was president, saying:

It is obvious that whoever pays the piper is going to call the tune. When you hold a carrot in front of a donkey’s nose, who is choosing the destination? […] [T]here is a real and present danger that, since the power to pay means power to control, little by little that power is bound to be exercised.

Professor Phillip Mechem, University of Pennsylvania Law School, 1958. Paul Tillett,” Law School Training for Public Responsibility,” July 1958. Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Report #003432, p.4, RAC.

What does this have to do with the civil rights movement of a few years later?

Professor Mechem’s concern illustrates a suspicion that perpetually accompanies philanthropic giving: money, even for charitable purposes, means control. A decade later, as Ford began to take interest in race and civil rights organizations, what would this power dynamic look like?

Ford’s Shift to Support African Americans

Between 1965 and 1970, Ford Foundation grants relating to African-Americans increased from 2.5% of total domestic programmatic outlays to a staggering 40%. This dramatic shift in grant funding coincided with new leadership at the top, but there was also a growing push among Ford’s program staff to support racial justice grantees more overtly.

Surveying the Field of Potential Racial Justice Grantees

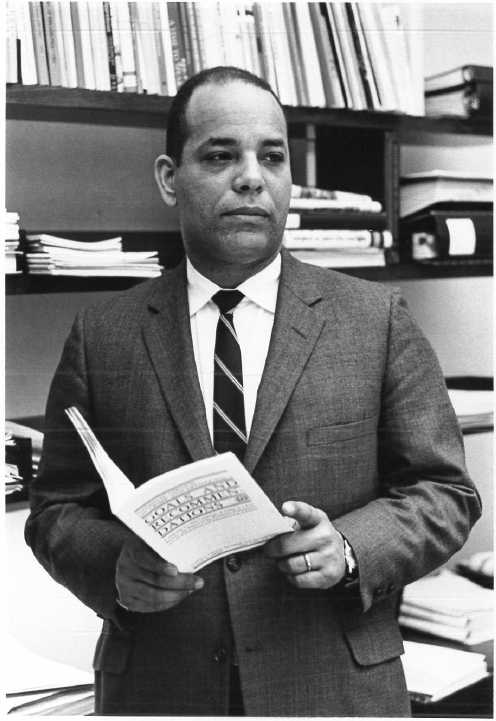

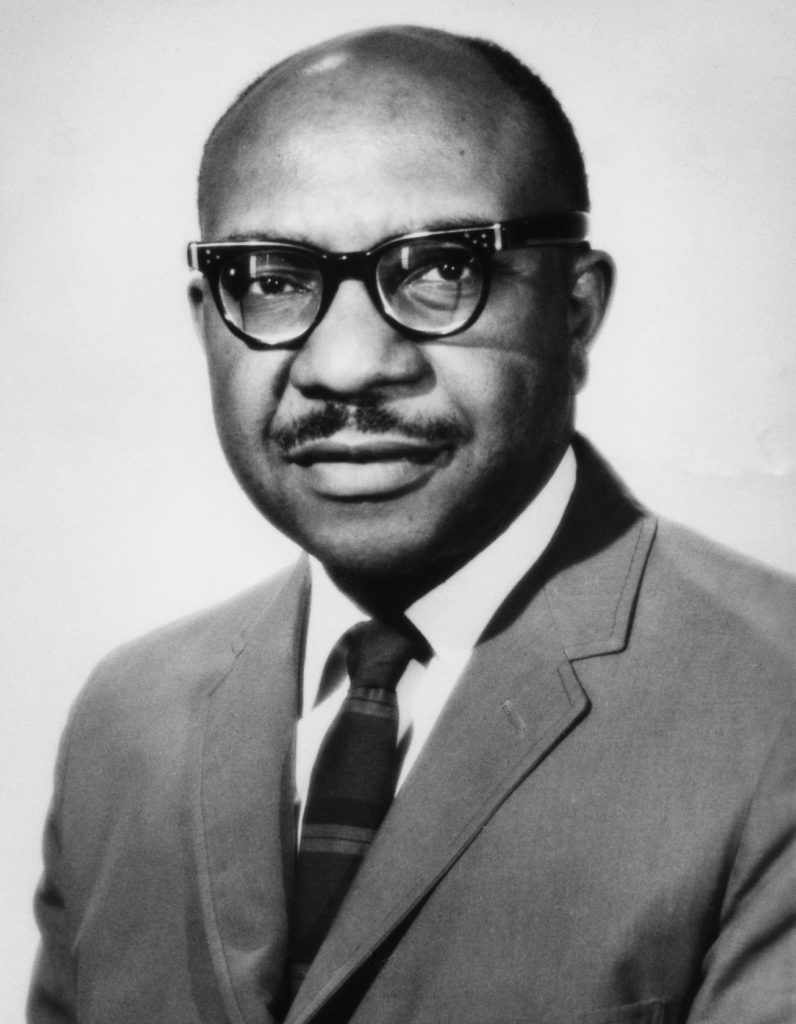

One such Ford program officer was Christopher Edley, a Harvard-educated lawyer who had served on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights until 1963, when he joined Ford. He was the foundation’s first African-American program officer. In 1965, with the Civil Rights Act newly on the books, Edley argued that the Ford Foundation had in fact done little to address the country’s racial issues head-on, and that Ford should be doing more to support the implementation of the Act.

Edley began with a hallmark of philanthropic programmatic planning: he surveyed the field of organizations working in this area — identifying potential grantees.

In fact, some of these organizations were technically already Ford grantees: the well-established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had received a small amount of direct Ford funding beginning in 1952, and the Southern Regional Council in 1953.“NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund,” Ford Foundation Records, Grants, Grant #05200070, Rockefeller Archive Center; “Southern Regional Council,” Ford Foundation records, Grants, Grant #05300021, Rockefeller Archive Center. However, most of Ford’s major support for tackling racial issues was carried out only indirectly, through offshoot funds the foundation had created in the early 1950s. The Ford-established Fund for the Advancement of Education, for example, supported extensive research on school segregation.“Ford Foundation records, Fund for the Advancement of Education (TFAE) files,” Rockefeller Archive Center.

What About Radical Civil Rights Organizations?

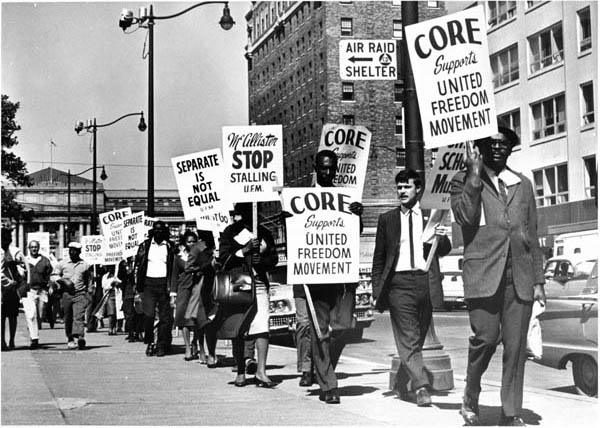

By the time Edley conducted his field survey, more action-oriented civil rights groups were making headlines, notably Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Edley paid visits to them all, but from his position as a Ford Foundation program officer, his overall assessment of building a funding relationship with these more grassroots groups was grim:

None has the capability of providing astute, progressive, continuing, and reasonable comprehensive leadership to the movement.

Christopher Edley, Ford Foundation Program Officer, 1965

Perhaps Edley had studied his audience: Ford Foundation president Henry Heald was known to be conservative when it came to racial issues. In fact, Ford staff at the time got the message — implicitly or explicitly — that the issue of race was strictly taboo.Several Ford staff members of this period mention the race taboo. See, for example, “Paul Ylvisaker,” Oral History, 1972-1979. Ford Foundation records, Oral History Project, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Surprisingly given his risk-averse leadership, Henry Heald approved initial explorations into civil rights grantmaking, after Edley powerfully argued the case.Dick Magat, who headed up Ford’s Office of Reports at the time, remembered the debate between Christopher Edley and Ford President Henry Heald, who was against staunchly against funding civil rights and worried about being caught off guard. Conversation with the author, April 7, 2016, New York City. Edley secured some modest support for the well-established NAACP.

Philanthropy Must “Pick and Choose”

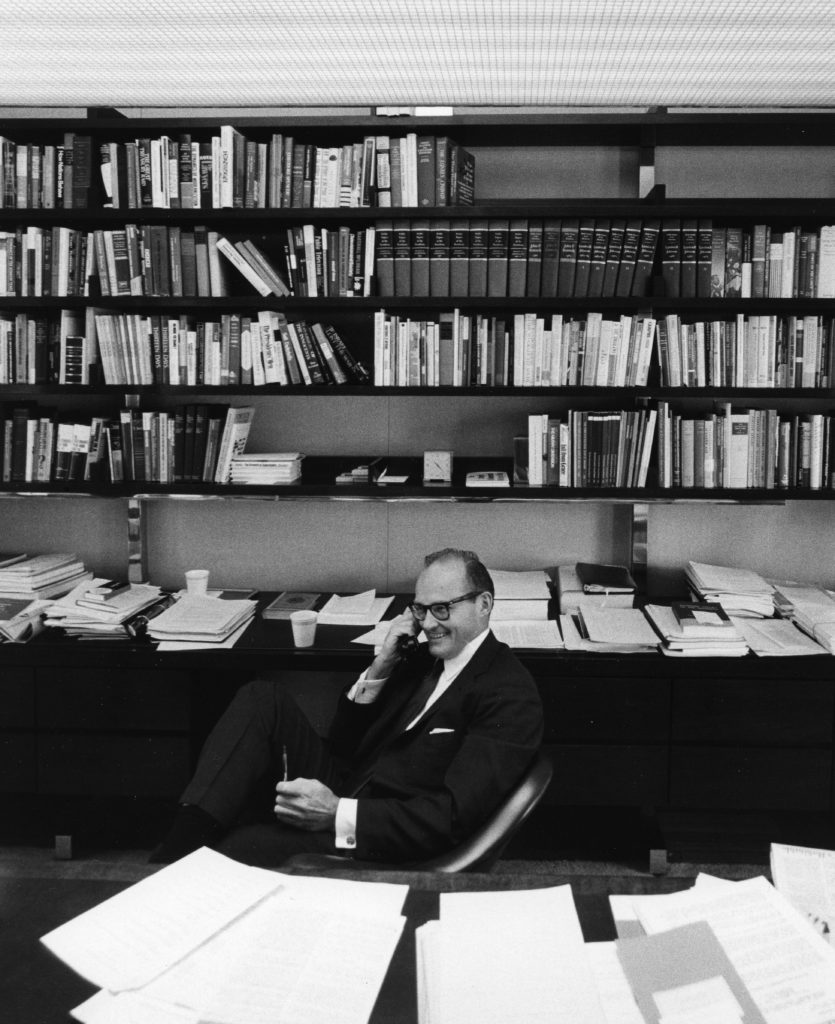

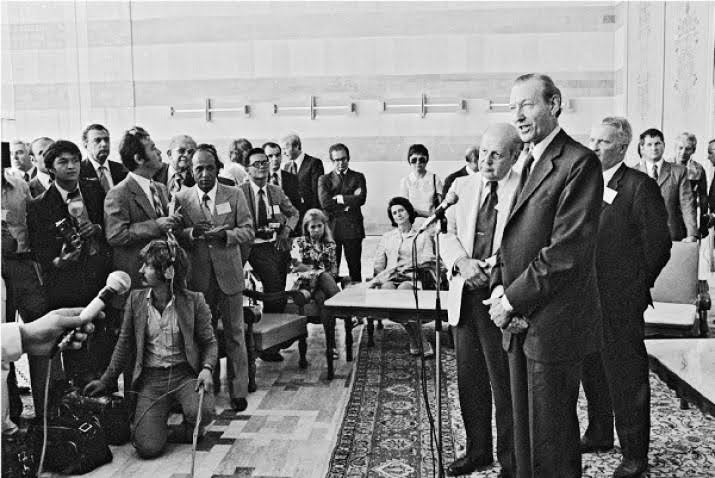

The following year, Ford had a new president fresh from the highest ranks of government: former national security adviser McGeorge Bundy. In August 1966, in a speech delivered at the National Urban League in Philadelphia, Bundy announced his organization’s shift to address civil rights.

We believe that full equality for all American Negroes is now the most urgent domestic concern of this country.

McGeorge Bundy, August 2, 1966.“Address by McGeorge Bundy, President, the Ford Foundation, Annual Banquet, National Urban League, Inc., Philadelphia” Ford Foundation Records, Catalogued Reports, Report 002908, 1966, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In the speech, Bundy acknowledged that the role philanthropy — and the Ford Foundation in particular — would play would be minor compared to the demands of the movement.

The greater share of the burden of effort falls now, and must fall in the future, upon Government at all levels, and upon the business concerns whose role it is to provide new opportunities for all Americans. However good our intentions, those of us who have a philanthropic responsibility will be forced to pick and choose on a tightly selective basis. This is a familiar problem within the Ford Foundation, and we do not shrink from it.

McGeorge Bundy, August 2, 1966.“Address by McGeorge Bundy, President, the Ford Foundation, Annual Banquet, National Urban League, Inc., Philadelphia” Ford Foundation Records, Catalogued Reports, Report 002908, 1966, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Over the next years, Ford’s millions would go on to fund new diversity fellowships, institutional support for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), diverse arts organizations, African American Studies departments at universities, and more.Noliwe M. Rooks, White Money, Black Power. The Surprising History of African American Studies and the Crisis of Race in Higher Education. Beacon Press (2006).

Choosing Moderate Grantees

The venue for Bundy’s August 1966 speech, the National Urban League was symbolic, and an indication of the “picking and choosing” his foundation would be carrying out.

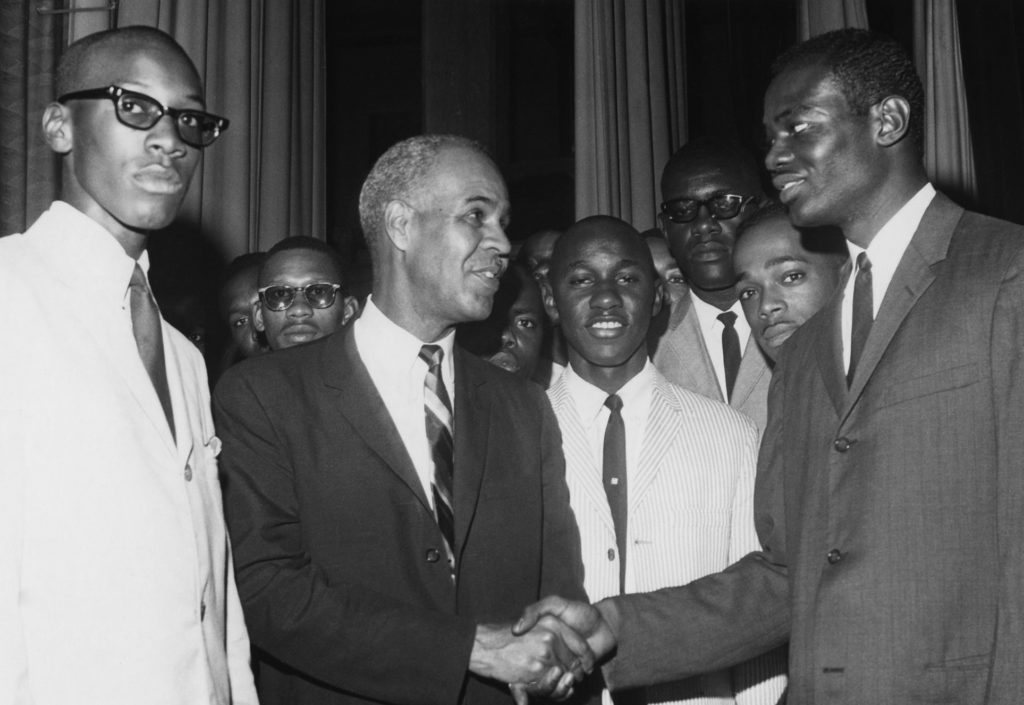

The National Urban League had been founded in 1910 and by the 1960s was considered (by civil rights supporters) “moderate” on the spectrum of civil rights organizations. At that time, the Urban League worked primarily towards African-American economic advancement through education, job training, and housing — a far cry from the protest action and Black Power ideology espoused by newly emerging groups.

Although relatively new to the Ford Foundation, the National Urban League was in fact a longtime partner and grantee of several philanthropic funds, including the General Education Board, the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Taconic Foundation, and others.Archival records related to philanthropic support for the National Urban League can be found in General Education Board Records, Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Records, Rockefeller Brothers Fund Records, Projects (Grants), and the Taconic Foundation Records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In 1966 alone, $600,000 from Ford enabled the Urban League to acquire a new headquarters building. Another $1.5 million from Ford supported demonstration projects “to improve the availability of housing opportunities for nonwhite families.” Another grant supported the Urban League’s family planning education program.“National Urban League, Inc.” Grant #06600139, $600,000; Grant #06600153, $1,500,000; Grant #06600141, $375,000; Ford Foundation records, Grants L-N, Rockefeller Archive Center. A highly professionalized organization (like the Ford Foundation itself), the National Urban League was the civil rights group to receive by far the most Ford funding in the period 1965-1970.

Similarly, the NAACP seemed a safe bet in the eyes of Ford Foundation staff, especially given their track record of successfully arguing the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case.Success may be an overstatement, given that full school desegregation was only incrementally implemented and ultimately abandoned at the federal level. In 1966, Ford awarded the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (NAACP LDF) with $1 million to create “a national office for the rights of the indigent” — a legal aid program. In 1969, another Ford grant of $1.15 million provided general support for the LDF.”NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.” Grant #06700080, $1,000,000; Grant #06900591, $1,150,000; Ford Foundation records, Grants L-N, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Incremental Progress Along a Middle Road

For a foundation seeking to leverage its resources, investing in organizations with a half-century of experience is not at all surprising. In fact, this practice is in line with what Ford and other large foundations had been doing in all fields of endeavor. Furthermore, it’s worth remembering that the Ford Foundation as an institution had not directly or overtly supported anti-racist efforts until 1966. The race “taboo” was well-established and so, perhaps, the mere willingness of the foundation to acknowledge that the US had a race problem may have been a sign of progress.

What Ford staff felt they were able to do in response, however, may not have been as effective. As race riots peaked in 1967, and Black Power emerged with a new set of demands, uncomfortable Ford staff members sought to prop up the moderating forces within the movement to temper the extremes.See Ferguson, Top Down. There is also a discussion of this in an analysis of Ford’s 1970s shift to policing. See Sam Collings-Wells, “From Black Power to Broken Windows: Liberal Philanthropy and the Carceral State.” Journal of Urban History. September 18, 2020.

Civil Rights Radicals vs. Moderates

This funding impulse is what Herbert Haines, in his 1988 study of moderate and radical social action groups, calls radical flank effects.Herbert H. Haines, Black Radicals and the Civil Rights Mainstream, 1954-1970. University of Tennessee Press, 1988. This idea asserts that in a social movement, the existence of radical groups will either undermine or reinforce the position and objectives of the more moderate factions. Haines cites a quote from Malcolm X :

I want Dr. King to know that I didn’t come to Selma to make his job difficult. I really did come thinking that I could make it easier. If white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they’ll be more willing to hear Dr. King.

Malcolm X, 1965Quoted in Herbert Haines, Black Radicals and the Civil Rights Mainstream, 1954-1970. University of Tennessee Press, 1995.

In the case of African-American civil rights groups, Haines documents how media coverage of increasingly militant action led to an overall increase in financial support (from all donor sources), and that support was especially targeted to moderate groups.

This was as true for large-scale philanthropy as it was for individual donors: the groups garnering the most foundation support were the most long-standing ones. Ford Foundation staff admitted that these organizations were considered “old hat” but the long-standing reputation, infrastructure, and networks made them logical nodes of foundation activity.

Moderates are Too Radical for Racists

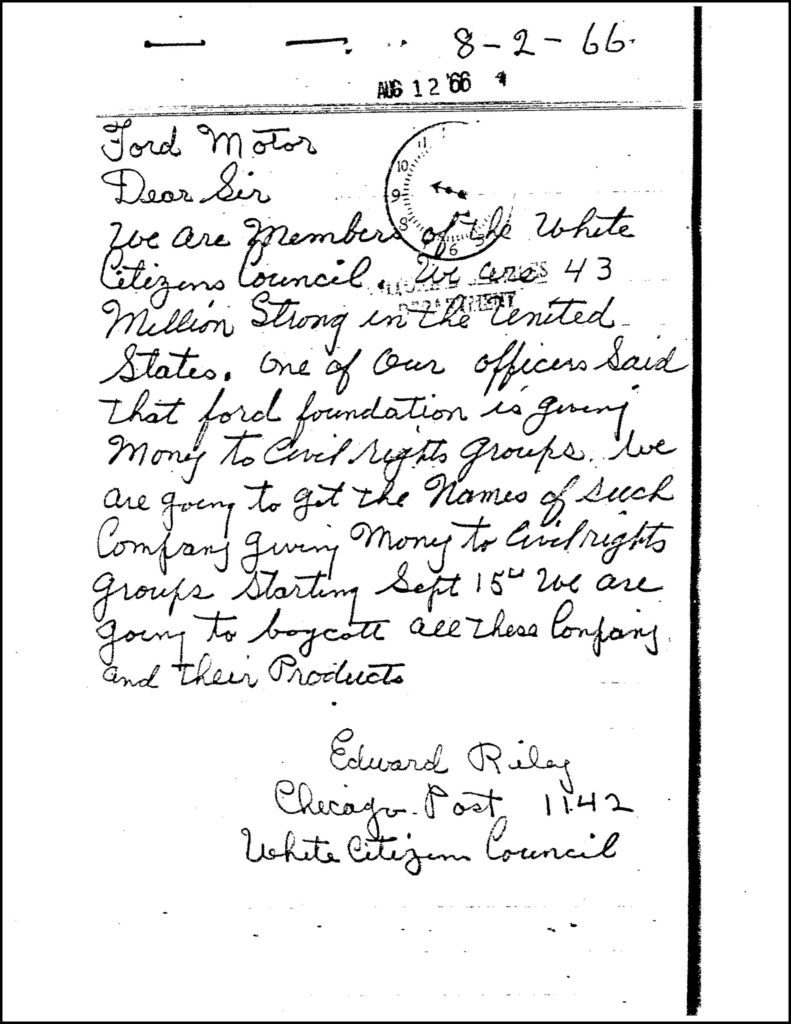

As Ford entered the field, even modestly and moderately, controversy ensued. Many white supremacists called for a boycott of Ford automobiles — conflating the independent foundation with the Motor Company. Hate mail poured in, and Ford automobile dealers were outraged.See, for example, a collection of letters forwarded to the Ford Foundation and preserved in the Ford Foundation records, “Ford Motor Co., Complaints about FF Activities, 1966-1967” Office of the President, Office Files of McGeorge Bundy, Rockefeller Archive Center.

If Ford’s funding impulses in the 1960s seemed cautious, Ford staff and leadership would soon learn what even moderate action could lead to. By 1969, it landed Ford Foundation president McGeorge Bundy on the floor of the US House of Representatives.

“Constructive Action”: Moderating Radical Groups

Although the National Urban League received the most Ford dollars of all civil rights groups in the late 1960s, the foundation also made some modest attempts to redirect the power and enthusiasm of loosely-organized “militant” groups. Ford’s “Social Development” program staff members hoped to encourage those groups to hone more professional practices and to build wider networks. A 1967 Social Development strategy paper was explicit about this:

Staff attention has been turned to the more militant civil rights organizations, specifically the Congress Of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Our interest in both is in seeing whether we may be of help to them in fashioning rational, goal-oriented programs of constructive action.

Ford Foundation Report, “Equal Opportunities for Minority Groups,” 1967“Information Paper: Equal Opportunities for Minority Groups,” 1967. Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Report #002835, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The sentiment here echoed that of the 1965 Edley report, which positioned the Ford Foundation as a possible moderating influence, to “reduce the dominant role of the man in the street.”

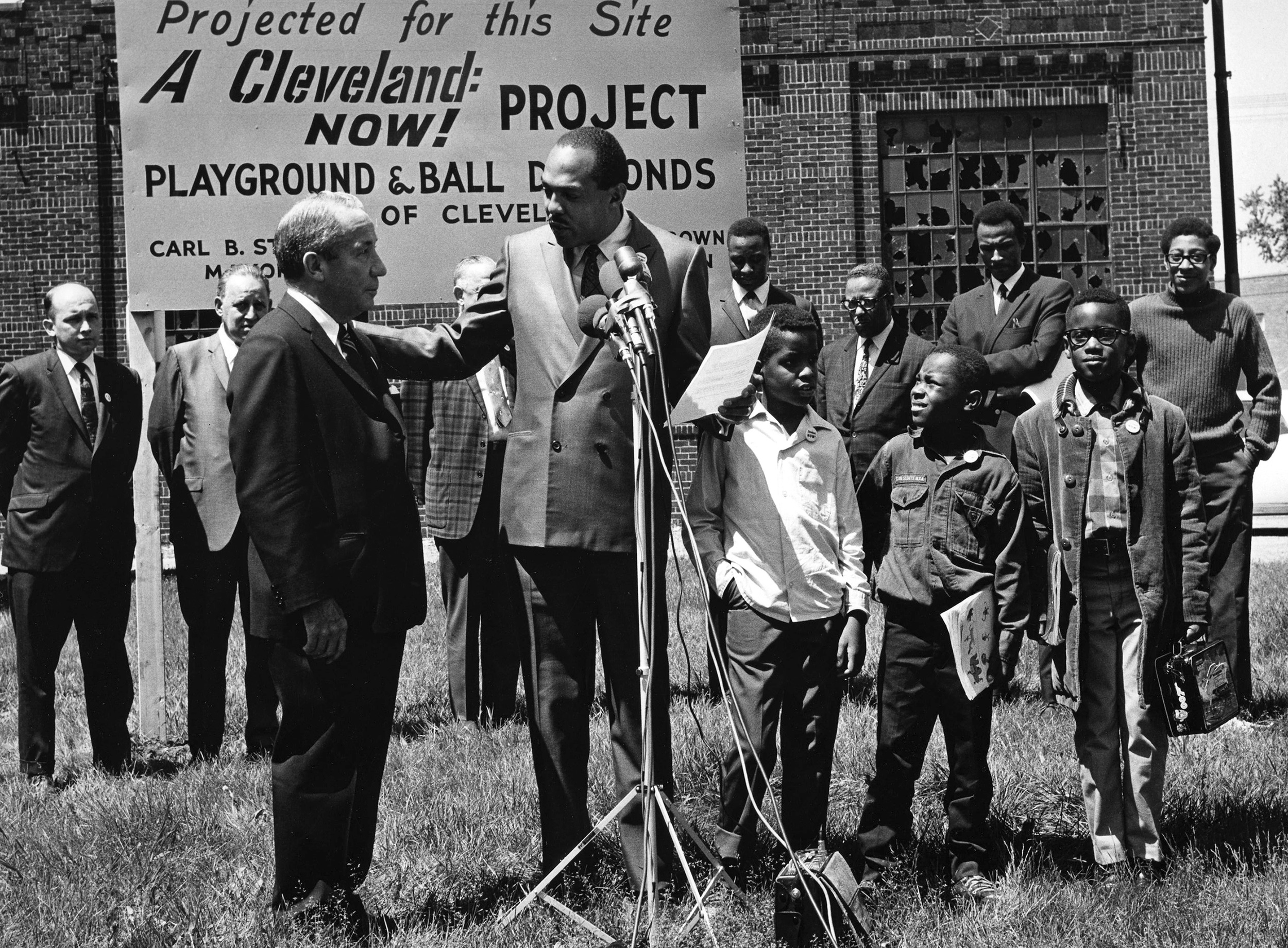

A Misstep? Ford’s Grant to Cleveland CORE

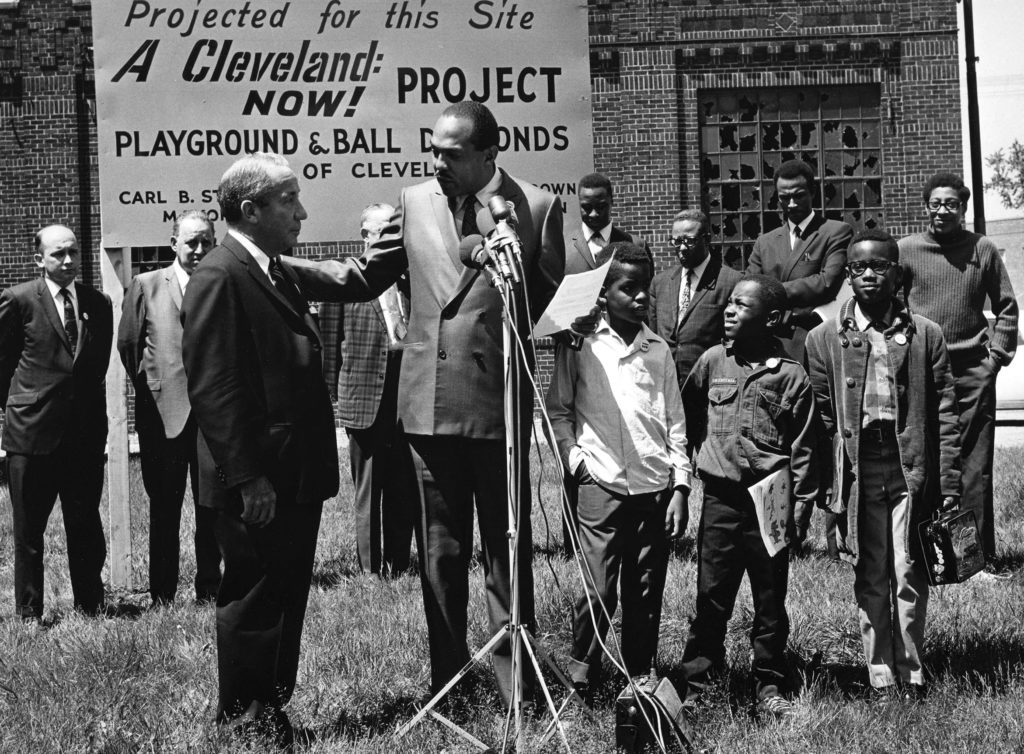

In this spirit, in 1967, Ford staff granted $475,000 to the Cleveland Chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality.“CORE Special Purpose Fund” Grant #06700446, $475,000, Ford Foundation records, Grants C-D, RAC. Their goal was to effect social change through education and democratic practice. One of the grant activities was a voter registration drive. That activity would propel Ford into a maelstrom of public outrage and, in 1969, onto the floor of the US House of Representatives.In fact, the Ford/CORE project was minor compared to the multi-year Voter Education Project, funded largely by the Taconic and Field Foundations, with additional support from the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Brothers Fund, among others. See Evan Faulkenbury, Poll Power. The Voter Education Project and the Movement for the Ballot in the American South. University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

One harbinger of criticism to come was that the registration project was not city-wide, but rather focused on Cleveland’s African American neighborhoods. These disenfranchised areas needed the most help, but given the context of Cleveland’s violent racial divisions, the grant’s focus on the city’s Black population was fodder for a backlash. Furthermore, CORE’s highly-publicized decision to remove the word “multiracial” from its mission made white liberals uneasy.

On July 14, 1967, the Ford grant made the front page of The New York Times.

The prescient Times article acknowledged that the grant “seemed destined to set off resentment” and posited that a voter registration drive “might increase votes for Carl B. Stokes,” the African American candidate vying for the mayoral seat.Douglas Robinson, “Ford Grant to Aid CORE in Cleveland.” New York Times, Friday July 14, 1967, p.1.

Mere months later, Stokes won the election and became the country’s first elected African American mayor.

A racist backlash hurled the Ford Foundation once again into a national debate about philanthropy’s role in politics and social movements. The accusation was that Ford’s intervention, via CORE, had in fact swayed the election in favor of the African American candidate.

Stokes’ victory also played into the accusation—promoted primarily in the southern states—that the New York-based Ford Foundation was fomenting urban unrest. Ironically, the Ford Foundation was trying to encourage more radical groups to take “constructive action,” to temper them through legal, democratic methods. But to conservatives, any association was too radical.

This reaction is indicative of a changing political context, a growing conservative backlash against social protest and seeking “law and order.” When Richard Nixon won the American presidency and took office in January 1969, he encouraged scrutiny of “liberal” foundations. Less than a month after his inauguration, Congress opened hearings to investigate foundations. To be sure, Representative Wright Patman had been looking into the role of tax-exempt organizations since 1961. Furthermore, the Cox and Reece investigations of the 1950s were still in recent memory. So a spotlight on foundations was not entirely out of the blue.Thomas A. Troyer, “The 1969 Private Foundation Law: Historical Perspective on its Origins and Underpinnings.” Exempt Organization Tax Review. January 2000. But Nixon’s victory and the 1969 congressional hearings moved the issue to center stage.

When Bundy took the stand, the CORE grant was a primary subject of interrogation. But he was prepared: Ford Vice President Mitchell Sviridoff had compiled background for nineteen Ford grants that “had some controversy associated with them.” The CORE grant was listed fourth. The SCLC grant, discussed below, was third.“Notebook, 1969, prepared in response to the Mills Committee (United States House Committee on Ways and Means) Investigation,” Report #012742. Ford Foundation records, catalogued reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In his 1972 oral history, Ford Foundation president Bundy claimed to have been persuaded that CORE was “a responsible and careful group.” But he argued that they were simply not sophisticated enough to take into account the political implications of their actions.

Funding Leadership Training

Also in 1968, Ford staff members made an attempt to pacify “the man in the street” by engaging with Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The group was holding a Minister’s Leadership Training Program in 1968, while word was also spreading that the SCLC might be planning a second March on Washington.

The week-long, Ford-funded conference for 150 African-American ministers was held in Miami that February. Civil rights leader and Presbyterian minister Bryant George — one of Ford’s seven Social Development program officers — was sent to observe and assess the program. He also kept an ear open to anything he might learn about plans for a second march.

In his written assessment to the Ford Foundation, George wrote that there was “too much rhetoric,” “extraordinarily poor planning,” and “no apparent continual evaluation.” These were all criticisms rooted in assumptions about proper, bureaucratic organizational behavior. Furthermore, he found that the tone of the older participants was too out of touch to speak to the “completely in-rebellion 16-30 year age group.” Of the meeting, he said “There was no real organization, and one was pleasantly surprised when anything happened as scheduled or indeed that there was a schedule.”Bryant George, “Martin Luther King, SCLC’s Ministers Leadership Training Program in Miami, February 1968, with specific reference to the ‘Poor people’s march on Washington for jobs and income,” Report #007991, 1968, Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports; and “Southern Christian Leadership Foundation,” Grant #06700580, $230,000, Ford Foundation records, Grants S-Thel, Rockefeller Archive Center.

there was no real organization…

Bryant George, Ford Foundation program officer, 1968

No Funding for a March on Washington

In his evaluation, Bryant George wrote a separate memo to address issues surrounding a “Poor People’s March on Washington for Jobs and Income” being planned for August of that year. In three pages, he takes great pains to insist that the march was not on the agenda for the Ford-supported Miami meeting. He specifically asked Dr. King and several other SCLC leaders about “their goals and purposes,” each of them insisting that the march was not on that list.Bryant George, “Martin Luther King, SCLC’s Ministers Leadership Training Program in Miami, February 1968, with specific reference to the ‘Poor people’s march on Washington for jobs and income,” Report #007991, 1968, Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Reading between the lines, it seems that George was responding to Ford leadership anxiety about being involved with “radical” protest action. The grant record supports this: the leadership training program was the first and only program grant Ford made to the SCLC. More radical groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee never received Ford Foundation dollars at all.

The Ford grants to CORE and the SCLC were small in the overall scope of that Foundation’s civil rights funding, especially when compared to the support for the National Urban League. But their political and public relations consequences convinced Ford staff members that trying to “moderate” such groups wasn’t fruitful. In each case, they were the only grant Ford made to the organization.

Choosing Movement Strategies

Given these experiences and the changing political context, by 1970, Ford Foundation National Affairs staff concerned with race and racism chose to focus efforts on civil rights litigation and public interest law. They also developed new ways to support minority enterprise and economic development using investment capital.

In making this shift, Ford staff members hoped that direct, protest action would be less necessary — and the movement goals more lasting. These are the strategies that Ford would follow in its domestic racial justice programming for the following two decades.

The public interest law firm emerged in the United States in the late 1960s and would quickly go beyond African-American rights groups to include other ethnic groups, women, consumers, and the environment. To be sure, Ford and other foundations had been funding public defender programs and legal education for decades, but the massive influx of resources to build free-standing public interest law institutions happened in a concerted, programmatic effort beginning in 1967.

By 1976, Ford had devoted nearly $31 million — approximately $130 million in 2016 dollars — to create and reinforce independent public interest institutions. Ford’s funding pattern to the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law from 1965-1970 is telling in this regard. The Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, the Native American Rights Fund, the Women’s Law Fund, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Environmental Defense Fund, and others have a massive Ford Foundation check in their birth story. Why? An internal evaluation paper from 1976 basically says that it’s about getting more bang for your buck:

The litigation dollar, with its focus on test cases involving large groups, tends to buy more than the community development dollar, which has to be spent on a wide variety of costly programs, such as housing and economic development.

Ford Foundation Evaluation Report, 1976

Nevertheless, those costly housing and economic development programs would be picked up by a new grantee type, the community development corporation (CDC) and a new funding mechanism, the Program-Related Investment (PRI). In the short space of this article, I can’t go into the details, but I will note that the PRI has a co-evolutionary origin story involving the Ford and Taconic Foundations in 1968. In a nutshell, the PRI is a mechanism for using part of a foundation’s capital — rather than endowment earnings — to make investments and loan guarantees to organizations regardless of whether or not they have 501(c)(3) status. In the late 1960s and 1970s, Ford used PRI’s to fund minority business development, nonprofit housing initiatives, and other projects.

New Grantee Relationships

In all of this, Ford Foundation staff in the late 1960s were developing new relationships with a new kind of grantee — going beyond the more established partners of the 1950s. The Foundation ultimately changed its own programmatic and funding strategies in the process. In an effort to follow the traditional philanthropy practice of tackling the “root causes” of a problem, Ford leaders and staff identified legal hurdles and limited economic access as the root causes of racial tension. The Foundation’s funding reinforced the Civil Rights Movement to those ends.

Others might rightly identify white attitudes or the economic system itself as the cause for racial inequalities. At the Ford Foundation of the late 1960s, an ethnically diverse but elite team of men (and precious few women) hoped that working with well-run and well-connected organizations would amplify the impact of Ford funding and lead to long-lasting effects — even when grassroots participants envisioned quite different ways to achieve their goals.

Further Reading

- Emma Schroeder, ““Food-Space-Energy Problems”: The Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the New Alchemy Institute, and the Emergence of Ecological Design in the 1970s.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2021.

- Nelson Flores, “Ford Foundation Support for Bilingual Education in the Civil Rights Era.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Kristoffer Smemo, “A New Dealized Grand Old Party: Labor, Civil Rights, and the Remaking of American Liberalism, 1935-1973.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Kira Lussier, “Personalities at Work: Psychological Testing and the Work Ethic in America, 1940-1980.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.

- Brian Purnell, “Unmaking the Ghetto: Community Development in Bedford-Styvesant during the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2013.

- Maribel Morey, “The Making of an American Dilemma: The Philanthropists and Social Scientists of the Civil Rights Movement.”Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2010.

- Timothy Thurber, “African American Civil Rights and the Republican Party.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2002.