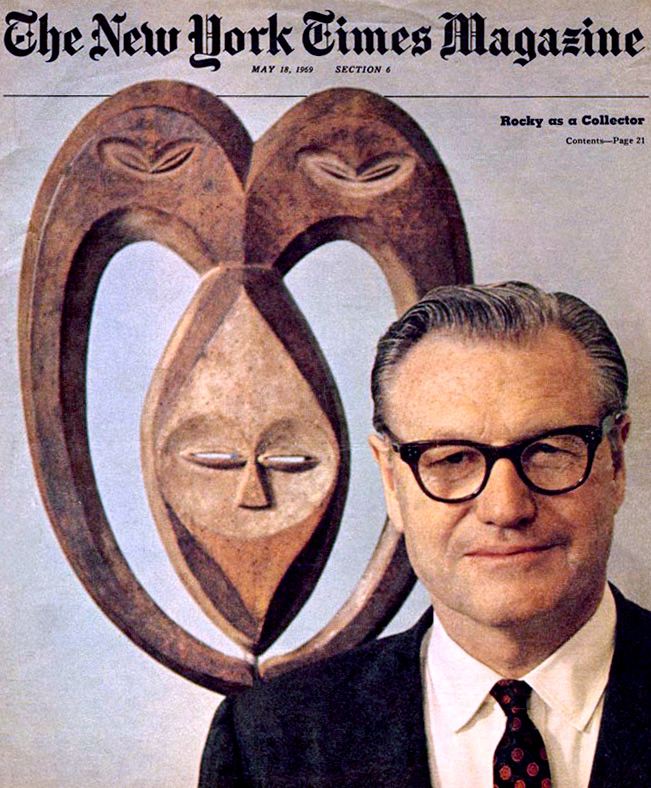

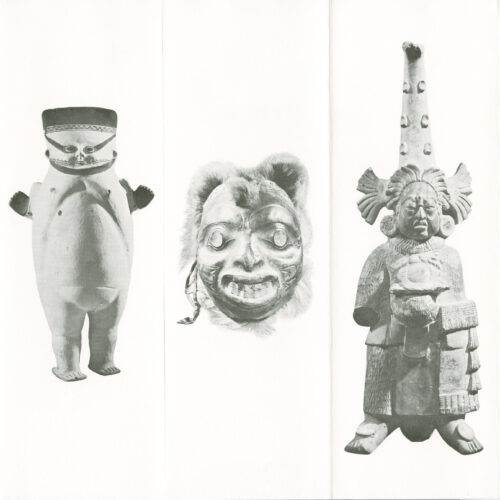

During the 1950s and 60s, Nelson Rockefeller made it a personal mission to uplift the reputation of indigenous art in the eyes of the fine art establishment. His 1954 founding of the Museum of Primitive Art in New York City—which housed much of his large personal collection—contributed to the legitimization of indigenous art for institutions and collectors alike.

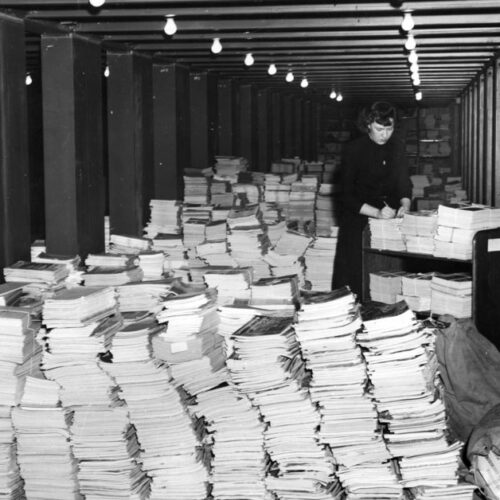

However, the museum’s success grew during a time of scrutiny on the antiquities market and an increased concern about ownership and cultural heritage.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, antiquity thefts were rampant in Central and South America, and often resulted in violence. Looters broke ancient monuments into myriad pieces, hoping to reap maximum profit through the sale of each individual fragment. In a letter to The Metropolitan Museum’s director, British Mayanist Ian Graham warned:

The looting situation here is worse, by far, than ever…at the third site [I visited] looters were actually at work…and shot my companion dead when we arrived…you’ve all got to do something damned soon or there will be nothing left for future archaeological work, and no intact monuments left.

Ian Graham to Thomas Hoving, March 23, 1971.Museums – Metropolitan Museum of Art – Primitive Art, Department of, 1969-1971; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

In a hot—and relatively unregulated—international art market, collectors as well as museums were frequent buyers of stolen goods. Furthermore, they were sometimes unaware of their newest acquisition’s troubled past. Rockefeller’s Museum of Primitive Art soon found itself in a sticky legal and diplomatic situation over a prized acquisition from Central America.

“A Smuggled Guatemalan Piece”

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) strongly argued that anyone in possession of stolen goods immediately return them to the country of origin.

In a 1970 Wall Street Journal article on stolen archaeological masterworks, William M. Carley documented one especially prominent return. By 1970, Nelson Rockefeller had discovered “a smuggled Guatemalan piece in his collection.” Carley noted that the Governor “says he plans to give it back.”William M. Carley, “Stolen Treasure: Archeological Objects Smuggled at Brisk Rate as Their Prices Soar,” The Wall Street Journal, June 2, 1970.

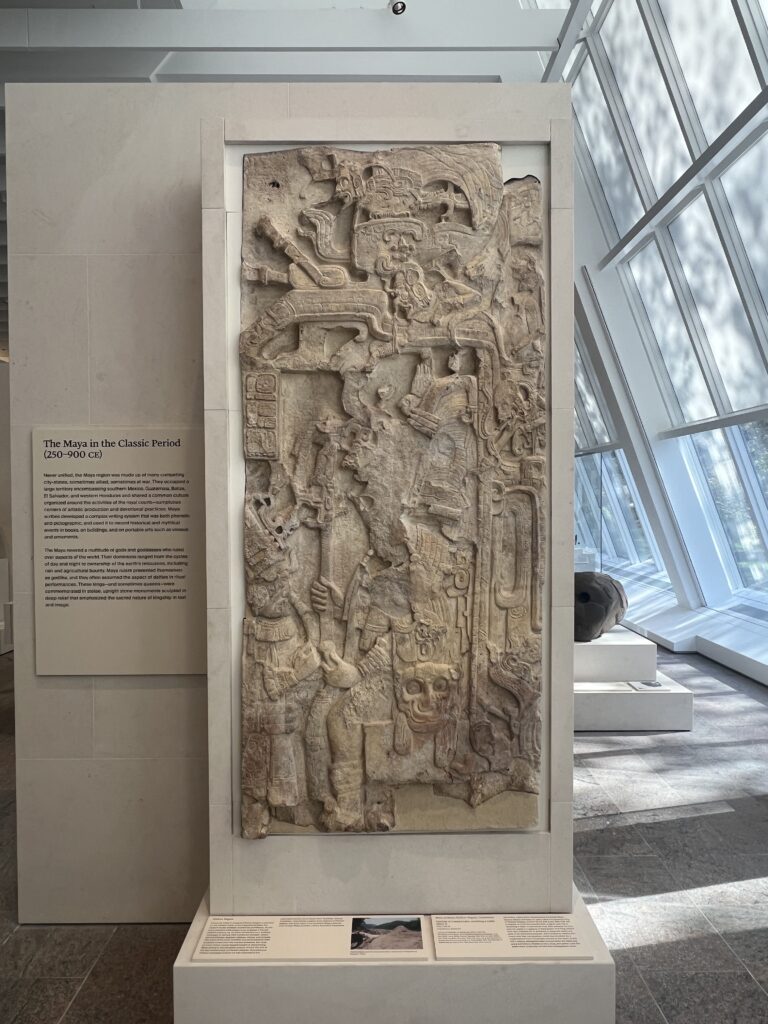

The piece in question was known as Stela 5, a stone slab delicately carved by Mayan royal sculptors during the 8th century. The stela had been taken from its original site in Piedras Negras in northwest Guatemala in the early 1960s.

The repatriation of this piece to the Guatemalan government was, however, no small matter. This high-profile controversy came at a contentious time between the United States and Latin America at the height of the Cold War. Furthermore, legalities around the antiquities trade were muddy and being renegotiated as formerly colonized regions fought for the return of their cultural heritage. This story illustrates how the public’s perception of a prominent philanthropist can sometimes create an opportunity for meaningful cultural diplomacy.

The Plundering of Latin American Historic Sites

The story of Nelson Rockefeller’s allegedly smuggled Mayan stela emerged during an era of great change for the Global South. Newly independent states strove to rebuild and regain their cultural legacy by reclaiming artifacts that had been taken as trophies of empire. Furthermore, they aimed to more forcefully protect the artifacts still within their borders from theft.

Meanwhile, the antiquities market boomed, and Mayan stelae were favored targets for looters. This was due to a combination of factors; stelae were found in remote parts of the jungle, and the region lacked state resources to keep them fully protected.

Unlike archaeologists, who carefully and legally excavated and documented historic finds, looters used a variety of methods to break the massive structures into more manageable pieces. This destroyed their historic context for the sake of a good price on the market. Archaeologists and scholars decried this carnage:

In the last ten years, there has been an incalculable increase in the number of monuments systematically stolen, mutilated, and illicitly exported from Guatemala and Mexico in order to feed the international art market. Not since the sixteenth century has Latin America been so ruthlessly plundered.

Clemency Coggins, “Illicit Traffic of Pre-Columbian Antiquities.” Art Journal, vol. 29, no. 1, 1969, pp. 94–114.

Nelson Rockefeller and Stela 5

In 1963, Nelson acquired Stela 5 from the New York dealer Everett Rassiga, Inc., from whom he also purchased several other Mesoamerican pieces. The stela’s provenance—its record of ownership since its discovery—had a few large gaps.

Rassiga purchased the stela fragment from Dr. Josue Sainz of Mexico City, who himself had purchased the fragment from Dr. Efrain Dominguez. At the time of sale, Dominguez reported his belief that the fragment “had been out of Guatemala for more than 35 years.”Robert Goldwater to John C. Eddison, May 26, 1966. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

The stela fragment entered Nelson’s collection at the Museum of Primitive Art (MPA), the institution he had founded in 1954. At the time, many curators believed that non-Western art belonged in museums of natural history rather than art museums. The Museum of Primitive Art was, in its own way, bucking the established order.

The Guatemalan Government Uncovers the Location of Stela 5

Stela 5’s new home in an American museum soon attracted the attention of the Guatemalan government.

On May 11, 1966, the Guatemalan Embassy contacted the US State Department. It claimed that the stela in the Museum of Primitive Art had been removed “without permission from the Guatemalan authorities.”

The Guatemalan Embassy didn’t accuse the MPA of being involved in the stela’s theft, nor did it dispute the Museum’s title to it. Instead, the Embassy requested the “voluntary return of the stela.” It argued that “no institution that calls itself a museum can accept for its collection works that have been obtained by looting or theft.”G. Raymond Empson III to Nelson A. Rockefeller, March 8, 1967. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

Regrettably, the antiquities market had operated for years with little regulation. The legalities regarding the ownership of historic artifacts—especially especially those of colonized regions—had remained in a gray area. This new era of decolonization demanded increased accountability from those collectors, dealers, and institutions who had previously overlooked an artifact’s incomplete provenance.

The Museum’s Legal Argument to Retain Stela 5

In the absence of clear evidence that Stela 5 had been stolen, the museum’s approach relied on the legality of its purchase.

Correspondence among MPA staff, Rockefeller, and legal advisors reveals that their inclination was not to return the purportedly stolen object. Instead, they felt that they should assert the fair title held by Rockefeller and the museum.Robert Goldwater to Thomas F. Killoran, March 22, 1967. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

Moreover, the museum feared returning the stela would set a precedent that could impact other museum collections. A Rockefeller family lawyer wrote:

With respect to the policy considerations, representatives of other New York museums have unanimously advised against the return, believing that such voluntary action would foster a raft of similar claims relating to objects in collections throughout the country.

G. Raymond Epson III to Governor Nelson Rockefeller, March 8, 1967Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

Possibly aware of the dangerous diplomatic waters that would be entered with an outright refusal to return a potentially stolen artifact, Rockefeller offered an alternative.

He suggested that the museum “Sell [Stela 5] for the price we paid for it.” While the museum would not relinquish title voluntarily, it could at least provide the Guatemalan government with an opportunity to redress the original, fraudulent purchase and return Stela 5 to Guatemala. In the process, Rockefeller would be compensated for what would amount to a $70,000 loss (roughly $690,000 in 2025).G. Raymond Empson III to Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller, March 8, 1967. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

…no institution that calls itself a museum can accept for its collection works that have been obtained by looting or theft.

Letter from Guatemalan Embassy, 1967

The RAC records are silent on the Guatemalan government’s response to Rockefeller’s offer. But soon, Stela 5 would be thrust more prominently into the spotlight.

The Met Gets Involved

In 1969, Rockefeller donated the Museum of Primitive Art’s collection to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. As a term of gift, he contributed to the construction of a new wing and established The Met’s first “Department of Primitive Art.”

Simultaneously, Rockefeller also donated a large portion of his modern and contemporary art collection to the Museum of Modern Art.

These large gifts soon became front page news. Consequently, the question of Rockefeller’s possession of an allegedly stolen artifact became more urgent.

An Appeal to Diplomacy

In 1969, Rockefeller met lawyer William D. Rogers at an event for the Center for Inter-American Relations. Rogers was the chair of an American Society of International Law panel devoted to studying the trafficking of international art.

In a letter to the Governor marked “Personal and Confidential,” Rogers argued that it would be politically expedient for Rockefeller to make a show of returning Stela 5 to Guatemala—without requiring repayment in advance. Rogers deftly appealed to Rockefeller’s sense of duty to both art preservation and diplomacy, referring to two instances of flooding that had recently put cultural artifacts in other areas of the world in peril:

Great international cooperative efforts were marshaled to preserve the Aswan Dam monuments and to repair the damage of the Florentine floods. In my judgement, the crisis now facing the Mayan material is no less serious from the standpoint of world culture.

William D. Rogers to Nelson Rockefeller, December 6, 1969.William D. Rogers to Nelson A. Rockefeller, December 6, 1969. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

Such a gesture by a sitting governor would, according to Rogers, “be received with great enthusiasm not only in Guatemala but throughout Latin America,” and would help the US to maintain friendly international relations.William D. Rogers to Nelson A. Rockefeller, December 6, 1969. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

Nelson Rockefeller’s Ties to Latin America

The diplomatic stakes for such a transaction were high for Nelson Rockefeller, who had a longstanding involvement with and interest in Latin America. For one, Rockefeller had been a trustee of Creole Petroleum, the Venezuelan subsidiary of Standard Oil, from 1935-1940.

In 1941, Rockefeller was appointed Coordinator of the Office for Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The OIAA’s activities included a media effort to counter the spread of fascist propaganda in Latin America during World War II. Additionally, it supported initiatives in agriculture and industry intended to foster development and economic growth in the region.

Following the dissolution of the OIAA in 1946, Nelson established the first of two other philanthropic ventures in Latin America. First: the not-for profit American International Association for Economic and Social Development (AIA), followed in 1947 by the for-profit International Basic Economy Corporation (IBEC).

Using different methods, each encouraged economic development and agricultural sustainability throughout Latin America.

Rockefeller also purchased several large tracts of farmland in Venezuela throughout the 1950s. He built a house on a property of more than 6,000 acres, which he named Monte Sacro.

As a prominent art collector, Nelson Rockefeller’s professional engagement with Latin America developed alongside his interest in its cultural contributions. He formed close relationships with the Latin American avant-garde of the time, including Frida Kahlo, Miguel Covarrubias, and Diego Rivera. In part through these relationships, Rockefeller became a proponent of Modern Latin American and pre-Columbian art.

By 1969, when his conversations with William Rogers took place, the AIA had closed down and IBEC worked mostly outside the region. But Rockefeller’s decades as a public servant, philanthropist, businessman, art collector, and landowner in Latin America were a part of his identity and his public persona.

Rogers thought that the significant positive feelings about Rockefeller in Latin America would guarantee the Guatemalan government’s agreement to the peaceful relinquishment of Stela 5’s title. Moreover, Rogers noted that Guatemala could likely be swayed to let Stela 5 remain on view at The Met in perpetuity “in tribute to your efforts to increase understanding of pre-Columbian art here.” William D. Rogers to Nelson A. Rockefeller, December 6, 1969.Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center.

President Nixon sends Rockefeller to Latin America

In truth, however, by the late 1960s, Rockefeller’s reputation in Latin America was more fragile than Rogers was aware of.

Since World War II, the United States had adopted a paternalistic approach toward Latin America. The US chose to prioritize the reconstruction of Europe and the containment of communism in Asia. Latin America’s concerns were frequently moved to the back-burner of foreign policy, fostering deep resentment.

That changed, however, when Fidel Castro’s communist revolution in Cuba brought the Soviet threat much closer to home. In response, the US began intervening in leftist movements across Latin America, going so far as to back anti-democratic—and often violent—autocrats.

In May 1969, in response to rising anti-US sentiment throughout the Latin American public, President Richard Nixon sent Governor Nelson Rockefeller on a goodwill tour as envoy and head of the Presidential Mission to Latin America.

Rockefeller’s presence had been specifically requested by Galo Plaza, secretary-general of the Organization of American States. He believed that Latin Americans would “respond more favorably to a personal emissary, someone like Nelson Rockefeller, a friend and advocate of Latin interests for thirty years.”Richard Norton Smith, On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller (New York: Random House, 2014), 543-544.

Rockefeller billed the mission as a “listening tour.” The plan to meet with leaders of twenty-three Latin American countries instead proved to be a complete disaster.

A Reputation Tarnished

Rockefeller was met with violent protests at several stops. Student demonstrators in both Honduras and Colombia were killed by national security forces.“Rockefeller Trip Sets Off A Clash; Honduran Student Killed by Police Gunfire in Protest — Governor Sees President,” The New York Times, May 15, 1969. Protesters set fire to the United States-Ecuadorian cultural center library. A “No Welcome” sign and thirteen supermarket firebombs anticipated Rockefeller’s visit to Argentina. These were just some of the demonstrations of resistance to his mission.

As a result, several stops on the “listening tour” were cancelled and Rockefeller returned to the US early.Richard Norton Smith, On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller (New York: Random House, 2014), 549-553.

Thus, at the time of his conversation with Rogers, then, Nelson Rockefeller’s public image in Latin America was not at all what it once had been.

On the one hand, Rockefeller’s direct involvement with Latin America for many years shaped his reputation with government officials as a prominent and influential American advocate for the region.

But, on the other hand, the Latin American public judged Rockefeller’s role as another destructive example of American domination.

In considering Rogers’ suggestion to return Stela 5 to Guatemala, Rockefeller may have been looking to recast public perception of his relationship to Latin America — smoothing over the tensions that had erupted on his diplomatic visit and restoring some of the “good faith” between himself and the people of Latin America.

Stela 5 is returned, legally speaking

By March 1970, Nelson Rockefeller not only had ramped up his approach to the return of Stela 5, but deliberately cast its return as a gesture of cultural diplomacy.

Writing to Guatemalan President Julio Cesar Mendéz Montenegro, Rockefeller stated that he was “now at liberty to give to your country the portion of the Mayan Stela which I purchased in New York a number of years ago.” Rockefeller requested that Guatemala “will agree with the Metropolitan Museum to loan it to them for an extended period so that it may there be enjoyed and admired.”

Nelson concluded his letter with the hope that

…perhaps this unfortunate occurrence can be turned into a positive gain for both our countries by entering into a period of closer cultural cooperation and exchange.

Nelson A. Rockefeller to Julio Cesar Méndez Montenegro, March 16, 1970Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

President Montenegro quickly responded. He agreed to keep Stela 5 on view at The Met as requested, and praised Nelson as “among the true friends of my country.”Julio Cesar Méndez Montenegro to Nelson A. Rockefeller, translated by “FPB,” May 5, 1970. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Collection – Guatemalan Mayan Stela, 1966-1970; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center.

An annotation from Nelson to his assistant, Louise, on President Montenegro’s letter vaguely hints at the public relations value he saw in press coverage of the 1970 “gift” of the looted Stela 5 back to Guatemala:

…I would think that now we could release story if requested. Also letter to Met. Then all to Pres. [sic]

Note from Nelson added to letter from Julio Cesar Méndez Montenegro to Nelson A. Rockefeller, May 5, 1970.

Certainly Nelson Rockefeller hoped that his “return” of Stela 5 held the potential to positively influence Latin American relations with the US. The technical return of the artifact as well as the quick agreement of the Guatelmalan president to keep it on view in the US might signal that this act was a one of friendship and generosity, and serve as a balm to a Latin American public suspicious of America’s, as well as Rockefeller’s, motivations in the region.

Stela 5 Today

Today, Stela 5 remains on view in The Met, credited as a loan from the Guatemalan government. While Nelson Rockefeller himself is not directly mentioned in the object description, Stela 5’s history as a looted artifact and The Met’s agreement with Guatemala is stated plainly:

With one piece of this monument in New York and the other at the site of Piedras Negras in Guatemala, Stela 5 exemplifies the legacy of a fraught and complicated history of looted objects and the need to work collaboratively to illuminate achievements of artists of the ancient world.

Portrait of a seated ruler receiving a noble (Stela 5), The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Stela 5’s role as part of a strategic diplomatic exchange connected to Nelson Rockefeller’s history of philanthropic activity in Latin America remains a little-known but integral chapter in its art historical narrative.

Related

“Opening Up New Worlds”: Nelson Rockefeller’s Quest to Redefine “Primitive” Art

Nelson Rockefeller’s personal collection of indigenous art – and the museum he founded to share it – would eventually become a vital addition to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “encyclopedic” collection.

Further Reading

- Stig Arild Pettersen, “Berent Friele: Nelson Rockefeller’s Shadow Diplomat in Latin America,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2025.

- Rafaela Silva Rabelo, “Latin American Education and the Good Neighbor Policy: Exploring the Projects of the Office of Inter-American Affairs,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2024.

- Vitor Loureiro Sion, “Nelson Rockefeller’s Report and Richard Nixon’s Foreign Policy towards Latin America,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2023.

- Elizabeth Barrs, “Creative Capitalism: Nelson Rockefeller’s Development Vision for Latin America and the World,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2023.

- Kathleen Berrin, “Nelson A. Rockefeller: U.S. Art Museums and Diplomacy Before, During, and After World War II,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2016.

- Ernesto Capello, “Writing the Gringo Patrón: Popular Responses to Nelson Rockefeller’s 1969 Presidential Mission to Latin America,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2009.