Self-infection for “Viable Eggs”

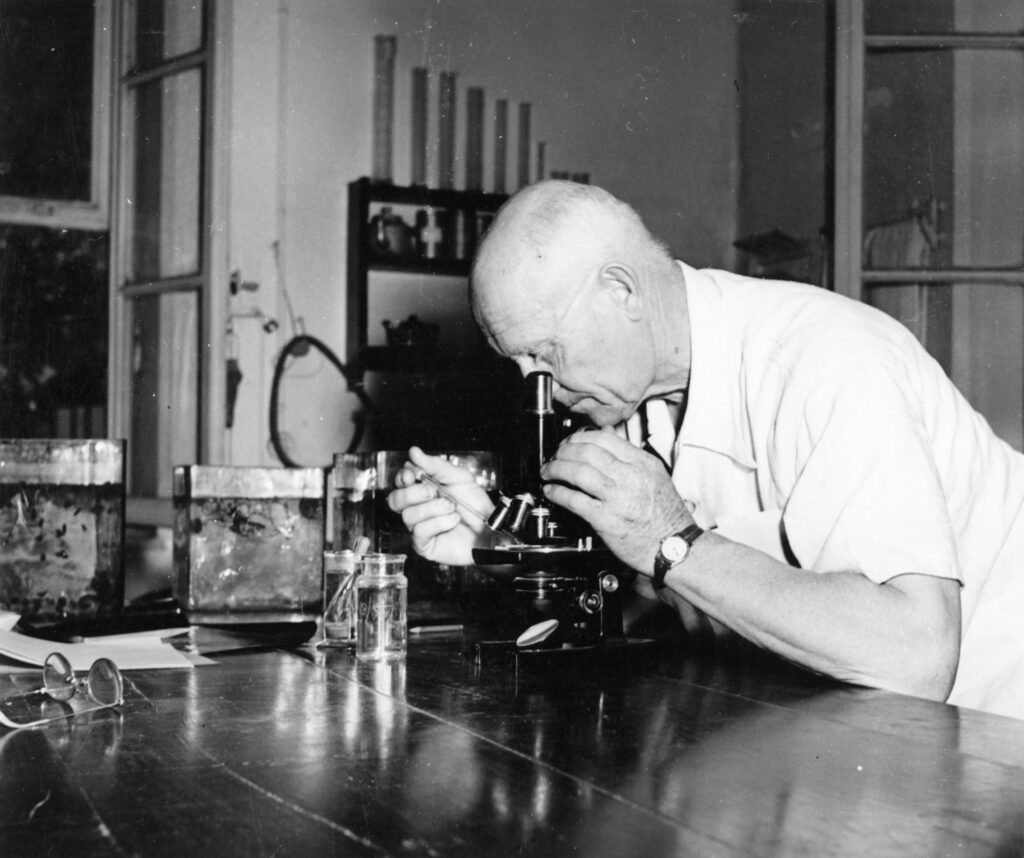

On May 11, 1944, Dr. Claude Barlow composed a letter to his colleague, Dr. W.H. Wright, chief of the Zoology Laboratory at the National Institute of Health in Washington, DC. Barlow was writing from his post at the Ministry of Public Health in Cairo, Egypt, where he had been working since 1929 as part of the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Division. He was one of the world’s leading experts on schistosomiasis, a disease that spreads through unsafe water containing snails that host parasitic worms. While Barlow had been working to combat this disease for over a decade, his research had recently taken a new, much more personal turn. He wrote to Wright:

I am infected myself. There was so much uncertainty about infected animals that I undertook to infect myself…. I wished to be sure to get the viable eggs to you. So there it is.

Claude H. Barlow, May 11, 19441942-1945; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

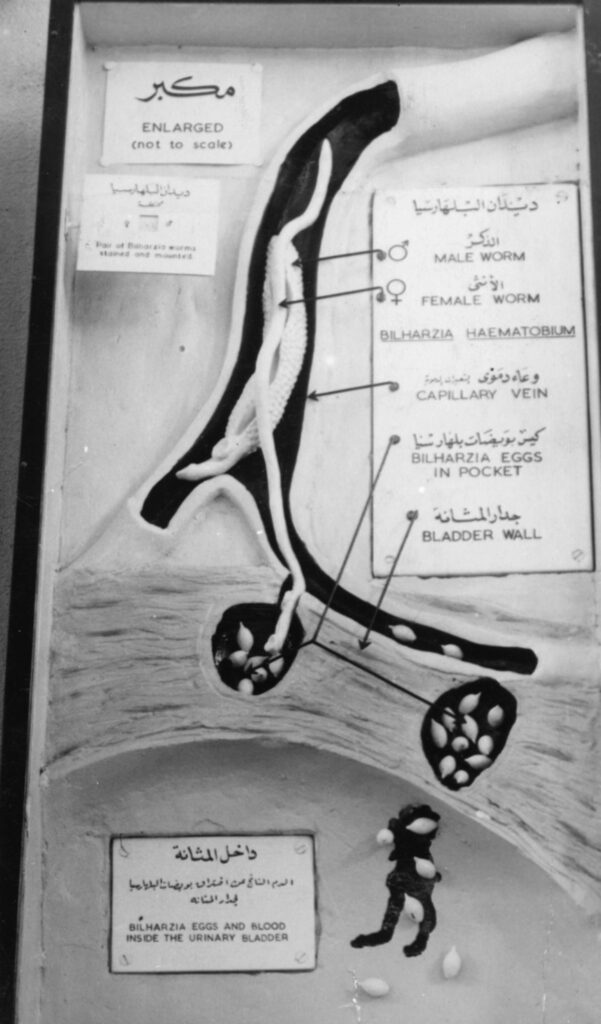

For months, Barlow had been working to transport viable samples of the parasitic worm from Egypt— where the disease was endemic— to the United States, where it remained virtually unknown. As the Second World War continued, some American soldiers stationed in North Africa became infected with schistosomiasis through contact with local water sources inhabited by the snails that serve as the main vector for the disease. Upon the soldiers’ return home, public health experts feared that the parasite could spread first to species of snails native to North America, and then on to other animal and human populations.

Crucially, in 1944 “there was no safe, simple therapy to eradicate the schistosomiasis-causing” parasite from the human body.Judith Sondheimer, “Claude Barlow: A History of Self-Experimentation,” Comparative Parasitology 90, no. 2 (2023):83. The best cure was prevention. Accordingly, it was vital for researchers in the United States to obtain samples of the parasite to determine if North American snails would be vulnerable to it.

Worm-Hosting Snails and the Search for a Human Model

The situation was delicate, as the samples would only be viable for study if they developed under certain environmental conditions. Snails host an immature form of the parasite, but several attempts to ship infected snails from Egypt to the United States were unsuccessful, as they could not survive the lengthy overseas journey. Infected mammals, including humans, could host the mature form of the parasite and would present a much more reliable and stable source of samples.

At first, it seemed as though there was an easy solution – one of Dr. Barlow’s Egyptian lab assistants was already infected and was willing to travel to the United States to aid in research. However, within the constraints of the wartime environment, officials at the National Institute of Health in the United States were unable to obtain the necessary approval from the US Immigration and Naturalization Service for the assistant’s travel.

The scientists also considered sending an infected nonhuman mammal, such as a baboon, from Egypt to the United States to provide a steady source of worm samples. However, researchers were uncertain if the parasite behaved the same way in baboons as it did in humans. Research on this species was still in its early stages, and Barlow and his colleagues feared that samples obtained from a nonhuman source would not allow them to accurately study the true risks posed to humans.

“Too Severe a Sacrifice”

It was, as Barlow said in his May 11th letter, this “uncertainty about infected animals” that ultimately inspired the scientist to take the drastic step of infecting himself. Wright, who seemed to anticipate his colleague’s intentions, had written earlier to discourage Barlow from putting his own health in jeopardy, stating: “This would seem to me to be too severe a sacrifice to ask of any one.”1942-1945; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center. By the time Barlow received that letter, it was too late – and he soon began experiencing the early signs of a schistosomiasis infection.

The risk Barlow had undertaken was not a small one. In 2025, the Centers for Disease Control defines schistosomiasis as the “second most dangerous parasitic disease after malaria.” It is one of several so-called neglected tropical diseases, affecting “more than 200 million people worldwide.”“About Neglected Tropical Diseases,” Neglected Tropical Diseases, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 6, 2024. The acute form of the disease can cause flu-like symptoms, such as fever, chills, and muscle aches, while a chronic infection can lead to stomach pain, blood in urine or stool, and organ damage. The infection poses a greater risk to children, who may also suffer from anemia and malnutrition as a result.

“A Torture of Fever”

Barlow, who was sixty-seven years old at the time of his schistosomiasis infection, experienced many of these symptoms over the course of the next several months. His experience was intensified as he continually declined treatment and presented himself as a subject for experimentation, both on his own and in cooperation with colleagues after his return to the United States in July 1944. In December of that year, Barlow underwent several biopsies of infected tissue, during which he refused the use of local anesthetic “for fear of disturbing the worms.”Self-Infection, 1944; Claude H. Barlow papers; Notes and Research Data – Series 3; Rockefeller Archive Center, page 17.

For about one month afterwards, Barlow experienced an acute illness which he later described as a “torture of fever, pain, tenesmus and constant urination.”Self-Infection, 1944; Claude H. Barlow papers; Notes and Research Data – Series 3; Rockefeller Archive Center, page 26. He theorized that his symptoms were caused by the parasites moving en masse to colonize different areas of his body following the biopsies. Throughout, Barlow took a clinical view of his experience, regularly recording his vital signs and meticulously examining his own bodily fluids for evidence of the parasite in its different life stages. In a later reflection on his illness, Barlow described it as “a most interesting phenomenon but one fraught with danger and distress to me.”Self-Infection, 1944; Claude H. Barlow papers; Notes and Research Data – Series 3; Rockefeller Archive Center, page 21.

Barlow was not exaggerating. A 1946 report, completed after his recovery from the schistosomiasis infection, stated that

As time went on Dr. Barlow’s condition grew more and more grave and by Christmas time 1944 he nearly died but he would not take treatment because he said, he had not finished with the work he set out to accomplish.

Horace W. Stunkard and Claude Barlow, 19461946; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

Clearly, Barlow’s choice to undertake self-infection – and to live with that infection for nearly a year – was extreme. What led him to this decision?

The Quest for Scientific Understanding of Schistosomiasis

Firstly, the scientific need for research on schistosomiasis was truly pressing by the waning years of World War II. In a personal account of his experiment, Dr. Barlow noted that, despite considering other options,

The danger of the spread of this most serious disease to the United States… seemed to me to be sufficient reason for making a thorough survey of the snails of North America to discover a possible snail vector. […] For such a survey a continuous, human source of schistosome eggs would be necessary.

Claude Barlow, 1944Self-Infection, 1944; Claude H. Barlow papers; Notes and Research Data – Series 3; Rockefeller Archive Center, page 2.

Having seen firsthand the devastating effects of widespread schistosomiasis infections among the population in Egypt, Barlow decided that the easiest and best solution was to serve as that human source himself:

It was because of the importance and urgency of the snail survey and of the firm conviction that no conclusive results could be arrived at unless the survey were conducted in the environment and that the source of eggs must be human, that I decided, after seriously considering all that such a step involved, to infect myself with S. haematobium. It seemed difficult, if not impossible, to find anyone else who would be willing to carry so dangerous an infestation for a period long enough to test out the snails of North America for possible vectors.

Claude Barlow, 1944Self-Infection, 1944; Claude H. Barlow papers; Notes and Research Data – Series 3; Rockefeller Archive Center, pages 7-8.

Claude Barlow’s Long History of Self-Infection and Self-Experimentation

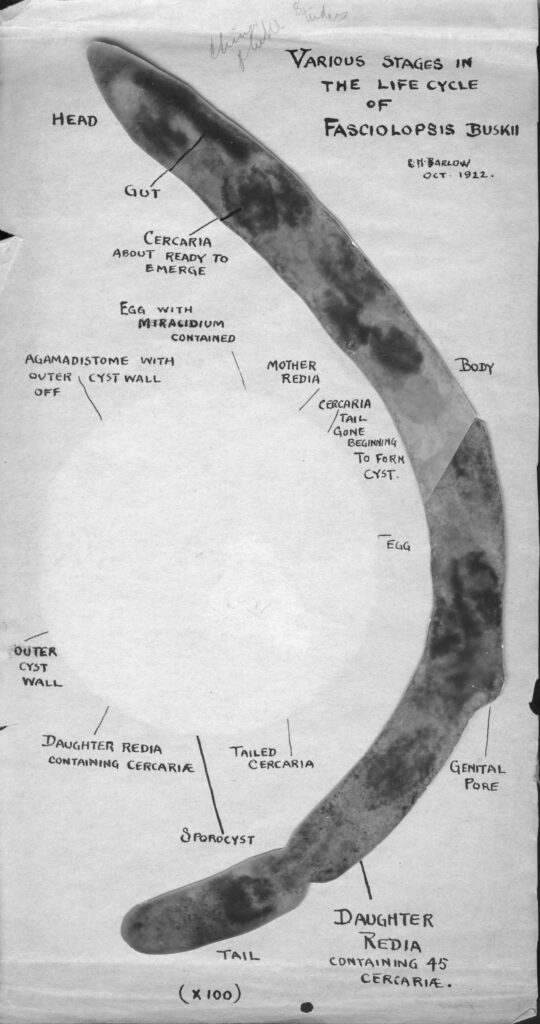

It turns out, the schistosomiasis infection of 1944 was not the Dr. Barlow’s first experience with self-experimentation.1947-1949; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center. While working at a mission hospital in Shaoxing, China in the 1920s, Barlow had conducted research on Fasciolopsis buski, a different type of parasitic worm also spread via snails in freshwater supplies. Like schistosomiasis in Egypt, fasciolopsiasis was endemic in the Yangtze River Delta region of China, causing serious illness and death in many of those affected.

Between 1920 and 1923, Barlow ingested the Fasciolopsis buski parasite multiple times, in one instance transporting “adult trematodes to the United States so he could have a continuous supply of ova for study during an 18 month sabbatical.”Judith Sondheimer, “Claude Barlow: A History of Self-Experimentation,” Comparative Parasitology 90, no. 2 (2023):83. Having used this technique successfully once, it seems Barlow opted to employ it again two decades later. Despite repeated parasite ingestions in the 1920s, he came down with active fasciolopsiasis only once. In his published study on the parasite, he cited the importance of “Having unlimited material at my command” in drawing conclusions about its biology.Barlow, Claude H. “Life Cycle of Fasciolopsis buski (Human) In China.” Chinese Medical Journal 37, no. 6 (June 1923): 466.

A Personal Passion to Understand Schistosomiasis

Aside from his desire to further scientific research, something else drove Barlow to now pursue a second, potentially more serious, self-infection experiment. For him, the fight against schistosomiasis had become a deeply personal one. He cared passionately about his work, having devoted the bulk of his professional career to studying how the disease spreads and how to prevent it from doing so. He had made significant personal sacrifices as well, choosing to live an ocean away from his family in America and turning down several offers of promotions and salary increases in order to keep on with the job that he saw as his calling.

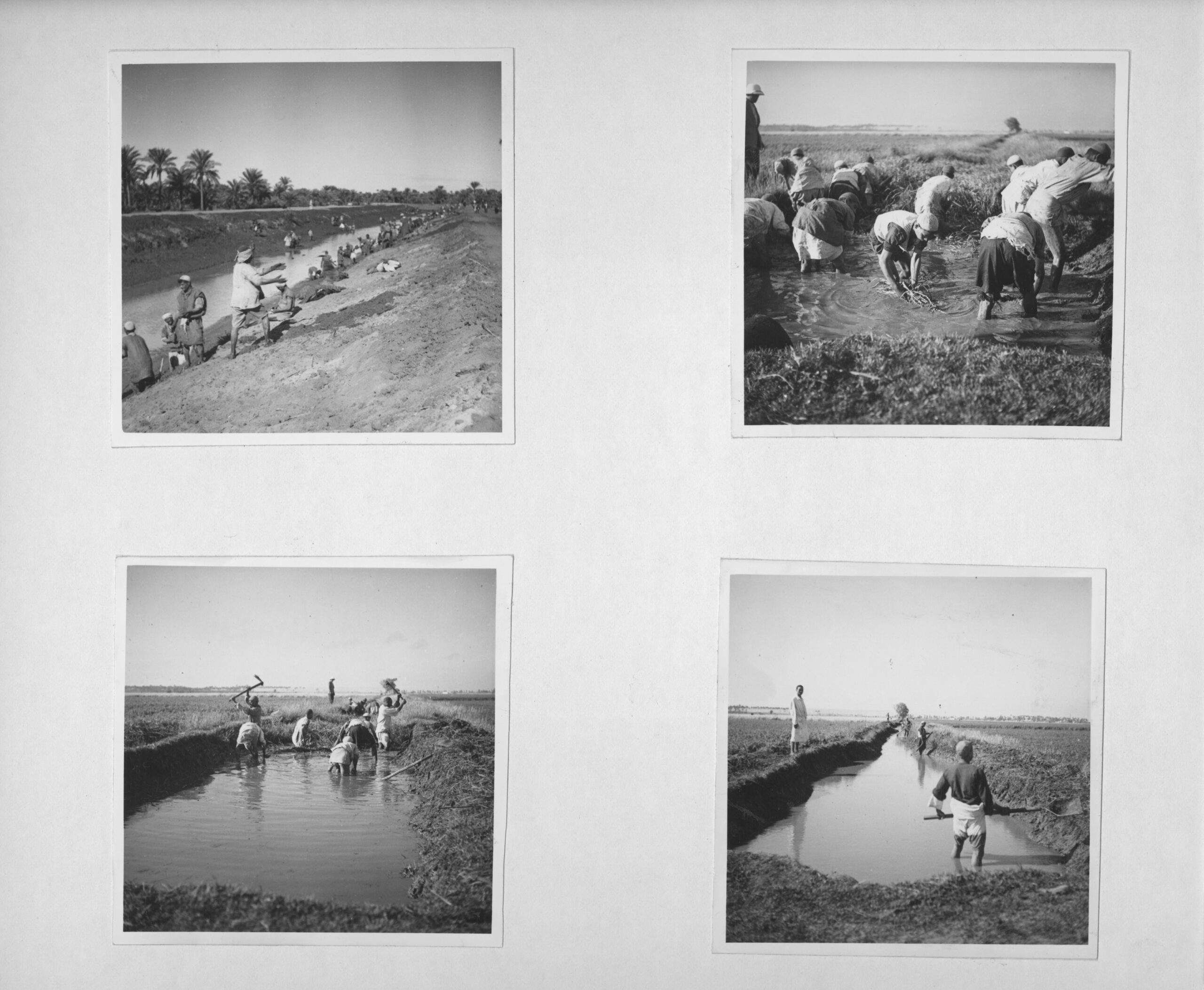

Barlow saw himself as uniquely placed to eradicate schistosomiasis in Egypt. This is because he knew that snails were the crucial vector of the parasite, and he had devised a method to remove them from the water supplies where transmission took place. If only he could put his method into practice, Barlow believed, he could help millions of people. But this was a job bigger than one person. Barlow could not do it by himself; he needed help.

Unfortunately, during his time working in the Egyptian government’s Snail Destruction Section, Barlow encountered conflict and repeated disagreements with colleagues. Despite and indeed because of his passion for the subject, Barlow found it difficult to work with others, even if they shared a common goal. In his drive to accomplish the work of eliminating schistosomiasis at all costs, at times Barlow sacrificed his professional relationships. Prioritizing what he saw as incredibly urgent, serious work, Barlow recognized that he did so at the expense of courtesy. He readily admitted that his words could be harsh, stating in an undated speech to his colleagues,

If I hurt anybody’s feelings I am sorry…. I am more concerned for the welfare of the Section that I am with my own feelings or the feelings of anyone in the Section.

Claude Barlow, undated speechPersonal, undated; Claude H. Barlow papers; Notes and Research Data – Series 3; Rockefeller Archive Center.

While Dr. Barlow struggled to remain patient, upon reflection he did express humility and an awareness of his own shortcomings. He went on to explain:

I have no wish to hurt anybody’s feelings but I do have a desire to help everybody and anybody I can…. My judgment is not always the best, I do not claim to be all wise, all good, all powerful, all knowing…. I do not aspire to position or power, I only want to see Egypt rid of her plague of [schistosomiasis].

Claude Barlow, undated speechPersonal, undated; Claude H. Barlow papers; Notes and Research Data – Series 3; Rockefeller Archive Center.

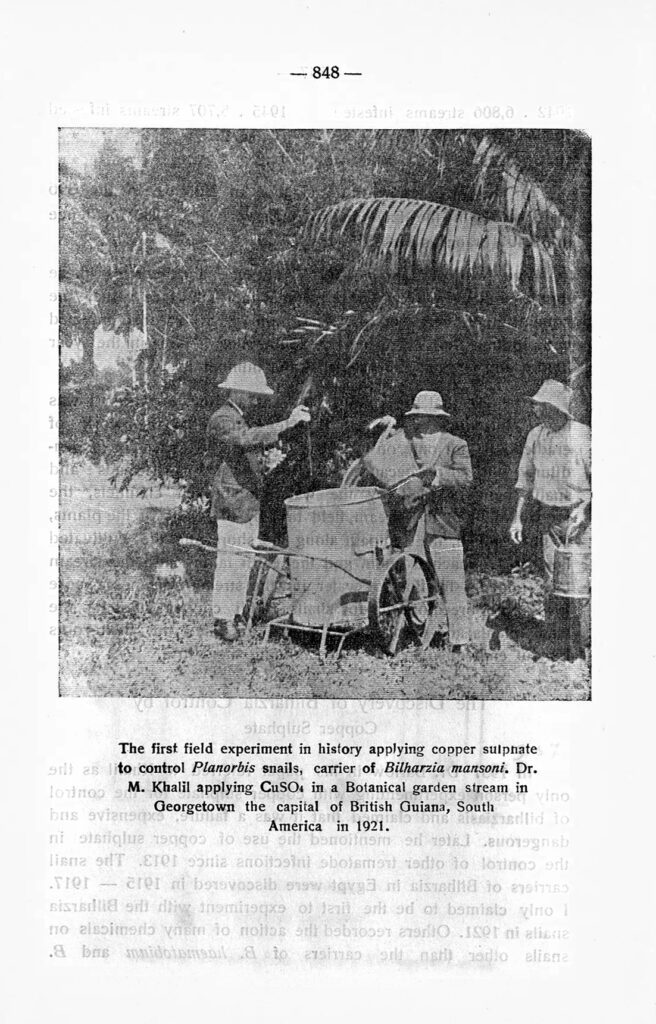

Dr. Mohammed Khalil Bey

Despite Barlow’s good intentions, one conflict in particular rose above all others – his troubled relationship with Dr. Muhammad ‘Abd al‐Khaliq Khalil (referred to in Barlow’s papers as Dr. Mohammed Khalil Bey). Khalil, an Egyptian scientist also working in the endemic disease sector since the late 1920s, strongly disapproved of Barlow’s scientific methods and questioned his motivations as a Western, American doctor imposing his own judgment and expertise on the people of Egypt. Clearly, the relationship between the two men was strained – Barlow’s papers contain copies of the passive-aggressive correspondence between them, as well as evidence of both openly criticizing one another in private and published texts.

This enmity was professional and personal, and no doubt heightened by how deeply each man cared about his scientific mission. For Barlow, it was difficult to move past what he saw as Khalil’s endless criticisms and personal jabs, and he meticulously documented any inconsistencies or errors in Khalil’s writing. For example, a 1941 letter from Khalil to Barlow is annotated with marginalia in Barlow’s handwriting: “No approval was given by the Undersecretary of State and he was quite annoyed at being so quoted.”1940; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

While the two men disagreed on many points, both recognized that the key to stopping the spread of schistosomiasis in Egypt lay with eradicating the vector snails from the canals and other fresh water sources where they could transmit the parasite to people. The main point of contention was how this process of “canal clearance” should be carried out. Put simply, Khalil favored the use of copper sulphate as a pesticide, while Barlow maintained that a combined approach of manual clearance, involving water drainage and removal of vegetation, and pesticide application was needed to fully eliminate the threat.

The scientists argued for years as to the best approach, conducting small-scale experiments in isolated areas to test their theories. Barlow criticized Khalil’s methods, alleging that he did not document his work properly and was not strict enough in designating experimental and control groups. Khalil fired back, claiming that Barlow’s proposed system would needlessly cost the Egyptian government more money and questioning his qualifications as an outsider who did not fully understand local culture and customs.

The progress of the Snail Destruction Section in coming up with a plan of action was painfully slow. Barlow felt himself blocked at every turn – as schistosomiasis continued to sicken and kill members of the local population, obstacles including scientific arguments, bureaucratic constraints, and the Second World War stood in the way. Despite his best efforts, the project he cared so much about had effectively ground to a halt. By 1943, when he received a letter from Dr. Wright at the United States Public Health service, Barlow was bordering on desperate.

A Dramatic Decision

Barlow was out of patience. He was sure that it was possible to stop schistosomiasis in Egypt, but there were so many factors standing in his way – especially Khalil. Without cooperation from his colleagues, it was impossible for Barlow to achieve his goal. Frustrated beyond belief, he decided that if he could not independently eliminate schistosomiasis in Egypt, the next best thing that he could do was stop the disease from spreading in the United States. If he could successfully complete a study of North American snails, he could make sure they either did not carry the disease or that they could be stopped from carrying it. All he needed to do was get the eggs to the United States.

As the prospects of his success in eliminating schistosomiasis in Egypt waned, Barlow grew almost obsessively dedicated to his new objective. The Public Health Service had originally requested only his “cooperation in obtaining… species of snails infected with S. haematobium,” in order to conduct their own study on the snails of North America.W. H. Wright, Letter to Barlow, September 11, 1943; 1942-1945; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center. When this proved impossible, Barlow took it upon himself to provide a human source of the samples as well as to envision an entire framework for the study, which he hoped and planned to carry out himself. Frustrated by his inability to singlehandedly cure the disease in Egypt, it seems Barlow was willing to personally do whatever it took to prevent it in the United States.

He did not give up this hope easily. On December 28, 1944, seven months into his infection and suffering acutely from alarming and unexpected symptoms, Barlow wrote in his diary that his colleagues “Dr. Segard and Dr. Meleney advised curing the disease but I refused because I still had hope that I would be asked to do an environmental survey of the snails of the U.S. and I could not jeopardize it all by losing the only human source of eggs in America.”Self-Infection, 1944; Claude H. Barlow papers; Notes and Research Data – Series 3; Rockefeller Archive Center, page 33.

By April 1945, Barlow had received final confirmation that his study would not go forward. On behalf of the Public Health Service, Wright wrote to express “regret that it was not possible for you to put your ideas into practice regarding experimental work on the transmission of schistosomiasis. We appreciate very much the part you have played in supplying infected material to various research workers in this country.”W. H. Wright, Letter to Barlow, April 4, 1945; 1942-1945; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Aftermath

No doubt with some reluctance, Barlow began a course of treatment on April 13, continuing to thoroughly document his symptoms over the next several months as the infection slowly subsided. It was a long and difficult road to recovery, but over a year later, on April 24, 1946, Barlow was finally able to inform a colleague: “There are no more eggs and I think that the case is closed except for such permanent damage as my tissues have received.”Barlow, Letter to H.W. Stunkard, April 24, 1946; 1946; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

In the same letter, he expressed hope that his scientific reports about his experience could contribute to research into treatments for the disease – a far cry from his original lofty goal of a comprehensive study of the snails of North America.

The effects of the infection were long-lasting. A 1946 report described him as “a much broken man physically,” stating that “he is suffering from ulceration of the bladder, cirrhosis of the liver, sterility, painful urination, and other chronic afflictions.”1946; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center. His situation was not entirely without recompense, as Barlow’s experience did further scientific knowledge about schistosomiasis – though not on the scale that he had hoped. In a letter sent from the Army Medical Center’s Division of Parasitology, Major George Hunter III thanked Barlow for the “splendid contribution” of samples of “S. haematobium eggs preserved in formalin…. I can assure you that many medical schools will be indebted to you for your kind cooperation.”George W. Hunter III, Major, Sanitary Corps, Division of Parasitology, Army Medical Center, Letter to Barlow, March 22, 1945; 1942-1945; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

Despite his harrowing experience, Claude Barlow returned to Egypt in 1945 to continue his work with the Snail Destruction Section. In early 1946, he wrote that “The schistosome work progresses slowly but we do move forward. There are areas wherein we have eradicated snails entirely and many others where we have reduced them to a point of real control.”Barlow, Letter to Dr. Strode, February 26, 1946; 1946; Claude H. Barlow papers; Correspondence – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

Dr. Barlow’s feud with Dr. Khalil Bey was reignited and indeed worsened as the men continued to disagree about nearly everything, including the best way to combat schistosomiasis. This conflict between them would unfortunately never be resolved, and the scientific mission to which they both devoted themselves is ongoing to this day.

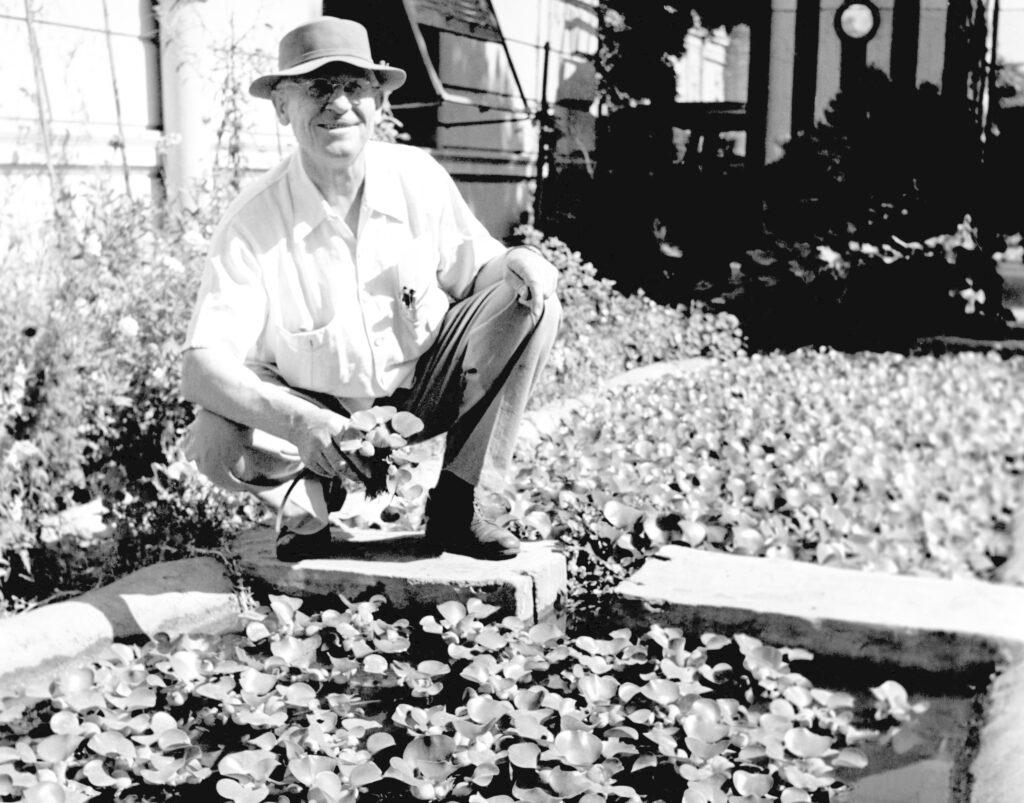

Barlow eventually left Egypt for good in 1951, at the age of 75. After completing a study on the snails of South Africa, he returned to his home in New Jersey and enjoyed a long retirement surrounded by his family.

The author would like to thank R.C. Miessler at Gettysburg College and Ed Bishop at the Wellcome Collection for research assistance.

Photo Gallery: Claude Barlow’s Schistosomiasis Research

Related RAC Research Reports

- Taylor, Stephen. “Claude Barlow and the International Health Division’s Campaign to Eradicate Bilharzia (Schistosomiasis) in Egypt, 1929-1940.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports (2019).