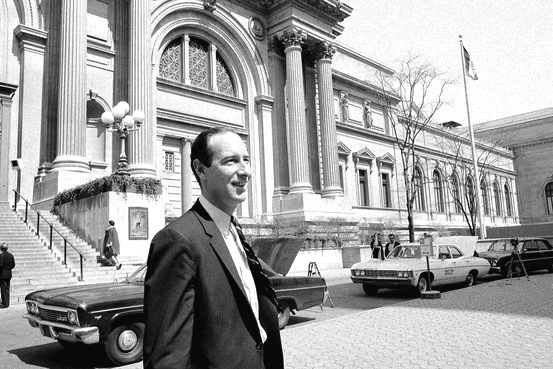

In May 1969, Nelson Rockefeller donated to The Metropolitan Museum of Art the vast collection of indigenous pieces housed at the Museum of Primitive Art since 1954. At the dinner announcing the gift to the public, Met director Thomas Hoving declared:

In my mind, it is a great and extraordinary moment for this institution. In a sense, we have come fully of age. In a very deep sense, we have filled out the encyclopedia of man’s creative achievement.

Thomas Hoving, May 9th 1969Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – General, 1956-1972; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers, Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

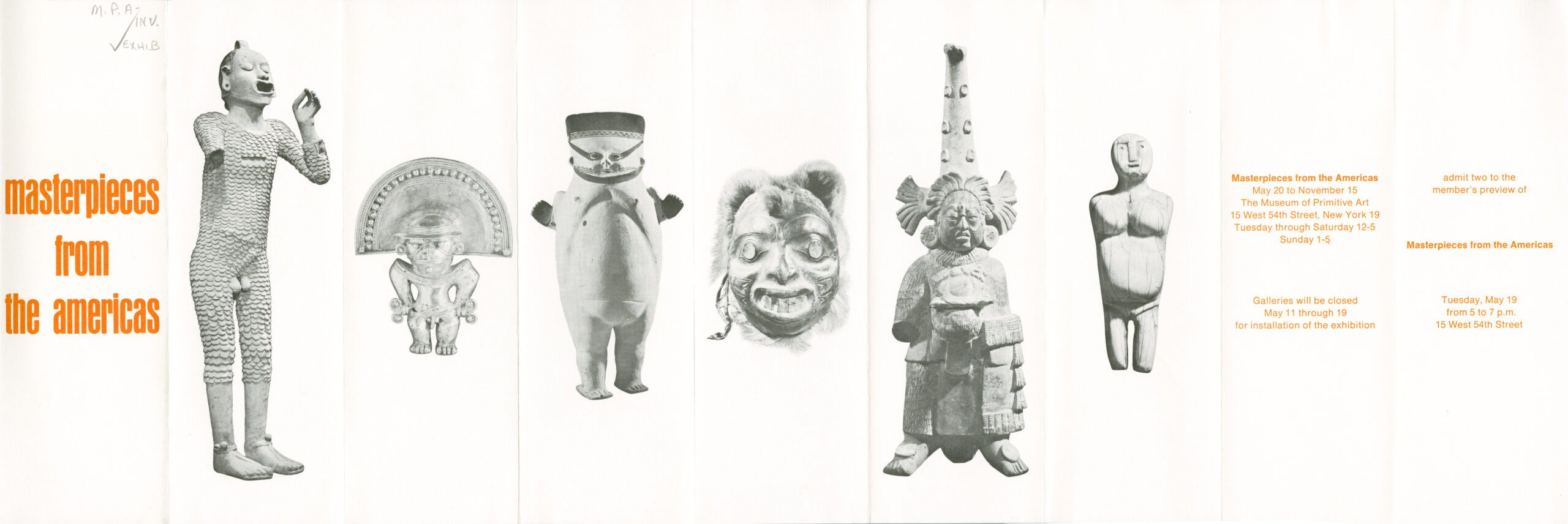

Fifty-six years later, in May 2025, The Metropolitan Museum of Art reopened its Michael C. Rockefeller Wing after a four-year, $70 million renovation. Named in memory of Nelson Rockefeller’s late son, the wing now displays roughly 1,800-pieces of indigenous art, representing works from Africa, Oceania and pre-Columbian Central and South America.

But Western elites had only recently considered these works “art.” Decades of collecting, advocacy, and the 1954 founding of the Museum of Primitive Art in New York City would eventually legitimize and integrate indigenous art into the world of elite Western art museums. What had changed?

Like many stories about museums, the story of this collection of indigenous art isn’t solely about the pieces shown in galleries. It is a story of an enthusiastic collector with deep pockets, the New York art establishment, clashing personalities, and the artists themselves.

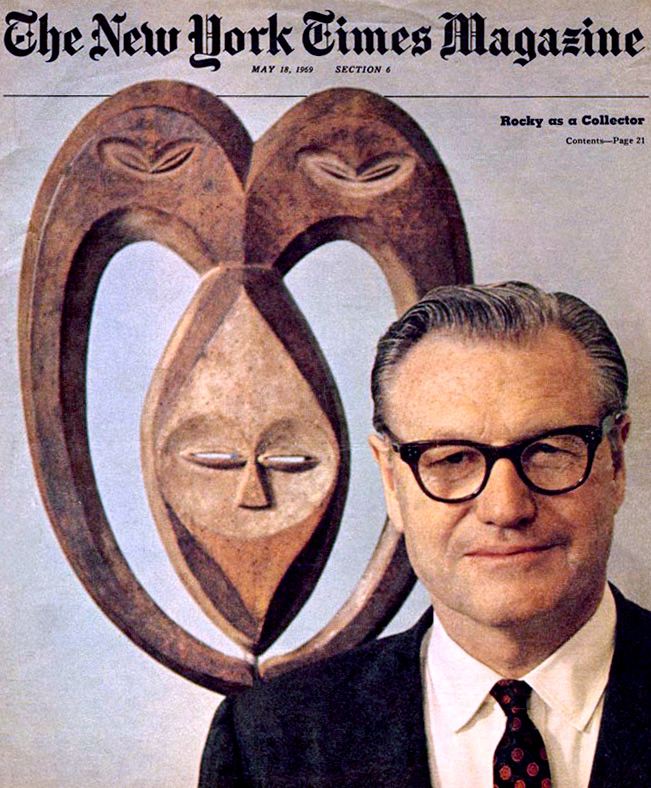

Nelson Rockefeller, an “Inveterate Collector”

It had been a longstanding aspiration for Nelson Rockefeller to give his non-Western art collection to as respected an institution as The Met. He had long been a self-proclaimed “inveterate collector” of modern and indigenous art.At the time of this publication, the more commonly-used term for this art is “non-Western.”

Yet, for much of The Met’s history — even after Rockefeller became a trustee — the museum did not present indigenous art with the same appreciation it did the European “masters” or ancient Egyptian “treasures.” Academics deemed indigenous works “primitive,” suggesting that the people creating them were trapped in the Stone Age past.

The art establishment looked down on so-called primitive art. Indigenous art was relegated to natural history museums, to further the study of anthropology or ethnography. Even contemporary works—in the chronological sense— were placed in galleries sandwiched between dinosaur fossils and taxidermy tigers.

There was, however, a growing population of antiquities collectors at midcentury who appreciated non-Western art for its aesthetic qualities—composition, expression, form, and craftsmanship. As Nelson Rockefeller put it in 1969:

It was the strength and immediacy of this art, created by people of cultures remote from our own, that first attracted me. You become aware of the unlimited imagination, quality and simplicity inherent in primitive objects. The force of the individual artist can be felt directly.

Nelson Rockefeller, Acoustiguide for 1969 Met exhibition. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – General, 1956-1972; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Rockefeller Archive Center

Two decades before his indigenous art collection finally made its way to The Met, Nelson Rockefeller had attempted to fill what he saw as a gap in the museum’s “encyclopedic” art collection. He had lobbied for The Met to support major archaeological expeditions in Latin America to identify indigenous works of art, but was rebuffed by museum leadership, who seemed content to uphold the standard that non-Western artifacts were not “art.”

And so, with an with an ever-growing niche collection of indigenous artwork, Nelson Rockefeller resolved to open his own museum. It would the first of its kind in the United States; dedicated to exhibiting non-Western art from around the world. However, the objective of the museum would not be to underline the “strangeness” of these lands or to exhibit the works in ethnographic dioramas. Instead, they would be presented as masterpieces worthy of artistic celebration and critique.

The force of the individual artist can be felt directly.

Nelson Rockefeller, 1969

Nelson Rockefeller and the Founding of the Museum of Primitive Art

Nelson Rockefeller was the son of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, who herself had co-founded the Museum of Modern Art. In a sense, Nelson was very much Abby’s protégé in arts philanthropy. He had the knowledge, the connections, the artworks, the space, and the funds to found a museum of his own. With the help of several colleagues, the Museum of Primitive Art opened February 21, 1957 in a remodeled townhouse across the street from the MoMA.

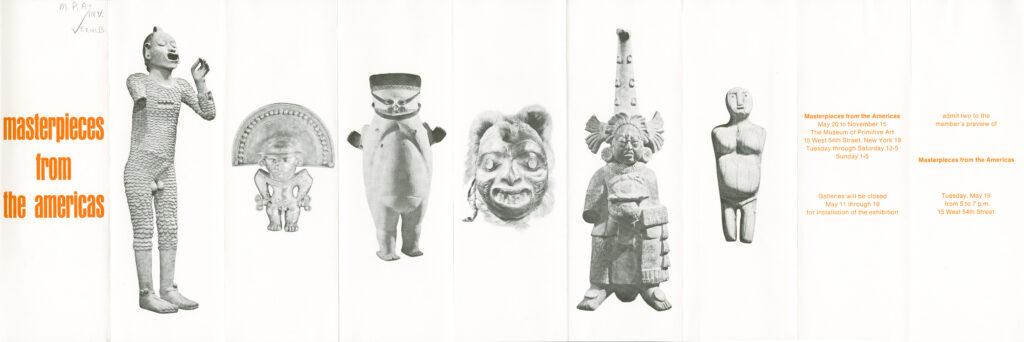

For a thirty-five-cent ticket, Rockefeller’s five hundred pieces of non-Western artwork were available for public viewing for the first time. Within the first year, the collection nearly doubled. During that time, the museum and its founder succeeded in acquiring several of the finest examples from Latin America, Oceania, and Africa.

It was the strength and immediacy of this art, created by people of cultures remote from our own, that first attracted me.

Nelson Rockefeller, 1969

In the Museum of Primitive Art’s first exhibition catalog, Nelson Rockefeller wrote:

We do not wish to establish primitive art as a separate kind or category, but rather to integrate it, with all its amazing variety, into what is already known of the arts of man.

During its brief existence, the Museum of Primitive Art helped to legitimize indigenous art for the first time in the United States. It held exhibitions of several private collectors and loaned out works to other museums around the world. The museum raised non-Western art’s profile worldwide, its value for collectors, and contributed significantly to its scholarship and conservation.

In a congratulatory letter to Nelson after its opening, MoMA’s Director of Exhibitions stated:

I believe you have done a tremendous thing for art in the twentieth century by opening your Museum of Primitive Art. By presenting worthily in New York the great art in this field which you have so discriminatingly assembled, you have pushed American cultural prestige one notch higher.

Monroe Wheeler to Nelson Rockefeller, February 20th 1957Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Letters of Appreciation, 1957-1971; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

It would take twenty years before The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s leadership eventually came around.

Nelson Rockefeller: Arts Advocate

Nelson Rockefeller was a major advocate of modern art. When MoMA opened in 1939, he served as that museum’s first president and brought international attention to artists such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. But Nelson had also fallen in love with non-Western sculpture, textiles, and crafts during his numerous travels around the world. His collection began with a simple wooden bowl he purchased on a trip to Hawaii in 1930. Later that year, he picked up a small sculpture of a female figure in Bali.

During a three-month tour of Latin America in 1933, in his role as a director of Creole Petroleum (a Venezuelan subsidiary of Standard Oil), Rockefeller visited Mayan ruins and explored collections of pre-Columbian art.

I found myself captivated by the power and exquisite refinement of these works. It was a most exciting and exhilarating experience, opening up new worlds—worlds little known and little appreciated at that time outside of Latin America and anthropological circles.

Nelson Rockefeller, 1978. Masterpieces of Primitive Art: The Nelson A. Rockefeller Collection. Douglas Newton, 1978

On a trip to Lima in 1937, Rockefeller tapped his network to advocate for the protection of several Peruvian mummies. Their preservation had been defunded by President Oscar Benavides. After an appeal from the beleaguered archaeologist-turned-politician Julio C. Tello, Rockefeller paid a call on the president. He argued that the mummies were international archaeological treasures and offered to fund their preservation. In the process, he added two mummies to his personal collection, which he eventually donated to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) for preservation.

Nelson’s First Proposal to The Metropolitan Museum

Rockefeller was inspired by the art and history of the ancient Americas. He had read about joint archaeological digs between the British Museum and Iraqi archaeologists, and proposed The Met and the AMNH could do something similar. In collaboration with local archaeologists, they could further conserve these objects and improve relations between the US and Latin America. As a reward, they would expand both museums’ existing collections of pre-Columbian art.

Rockefeller’s proposal was met with enthusiasm by the AMNH, but by disinterest by The Met’s director Herbert Winlock. The Met’s pre-Columbian collection was minimal at best, and Winlock was content to have the whole of it shipped across Central Park to live with the dinosaur fossils. Moreover, Winlock was a successful (and territorial) Egyptologist who feared that funding would be reallocated for a collection he felt would fit better with the study of natural history than the arts.

Unsurprisingly, a collaboration between The Met and the AMNH in this field did not came to fruition. Rockefeller later recalled,

The old boy told me to forget all that “native” stuff and spend my time and money on “good things” like Greek art.

Nelson Rockefeller, 1969Making the Mummies Dance: Inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Thomas Hoving, Simon and Schuster, 1993.

In fact, Rockefeller did not take Winlock’s advice; his collection only grew larger. His role as Coordinator for the Office of Inter-American Affairs under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt allowed him to continue to acquire even more pieces. As there was still no indigenous art museum in the United States, it seemed the perfect time to found one.

Primitivism’s Influence on Modern Art

It is well-known that modern artists were heavily influenced by African art in particular,as it offered permission to color outside the lines of the French Académie.Murrell, Denise. “African Influences in Modern Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–2008. Rockefeller’s own personal collection was dominated by both modern and non-Western art.

This embrace of “primitivism” by classically-trained artists helped to usher in an age of abstraction in Western art. By mid century, “primitivism” as a technique in modern art was well-recognized, even celebrated. Grandma Moses (1860-1961), Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985), Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) were admired precisely for their rejection of rules or their lack of classical training.

But this particular definition of “primitivism” didn’t apply to those who created the works in Rockefeller’s collection. If anything, it was appropriated from the very artists he wanted to celebrate. Highly skilled and and well-trained indigenous craftspeople were well-regarded in their communities. Yet their work was categorized as “primitive” and invalidated in the West.

Social Darwinism and the Prejudice Against Non-Western Art

Since early colonial times, Europeans brought back the art of native peoples as empires expanded and extracted the natural resources of Latin America, Africa, and the Pacific Islands. Trophies of these “exotic” destinations were often displayed in private cabinets of curiosity:

[…] a glimpse of a more curious and less scientific age, the 18th century, which picked out of its rarity cabinets, where it “kept cult objects and other savage utensils,” the most hideous examples in order to testify to “the strangeness and inhumanity of their customs.”

19th century physician and botanist Ph.Fr. De SieboldQuoted by Museum of Primitive Art Director Robert Goldwater in Primitivism in Modern Painting, 1938.

Furthermore, 19th and early 20th-century anthropologists often subscribed to a misinterpretation of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution referred to as Social Darwinism. Native cultures were portrayed as barbaric or romanticized as “noble savages;” relics of the past, uncorrupted by “civilization.” World exhibitions displayed indigenous art, weapons, and in some cases people, further contributing to dehumanize indigenous cultures and support the imperialist mission.

So-called primitive art suffered from this centuries-long racist characterization; consistently portrayed as unsophisticated, childlike attempts to imitate nature by people living in an earlier stage of cultural and intellectual evolution. The art establishment predating the rise of such modern movements as abstraction or fauvism measured an artist’s talent by how accurately they imitated nature in painting or sculpture. Therefore, it’s no surprise that indigenous art — which often used exaggeration or distortion for emphasis — would be seen as amateur.

The Darwinian theories, as we have already seen, had strongly influenced the study of primitive ornament; the development of art was treated as a part of natural evolution, and savage art was considered its lowest form.

Museum of Primitive Art Director Robert Goldwater, Primitivism in Modern Painting, 1938

This history supported the practice of categorizing indigenous art as ethnographic. It was used to demonstrate the stages of human creativity, but not go so far as to share gallery space with the great “civilized” artists of Europe.

The strangeness and inhumanity of their customs…

19th century physician and botanist Ph.Fr. De Siebold

This was precisely why Nelson Rockefeller’s vision for the Museum of Primitive Art was radical. Objects would not be placed in dioramas accompanied by regional tribal music. The craftsmanship of the artist, whether named or no, would be highlighted. Ethnographic and anthropological visual contexts would be removed so that the art could be appreciated on its own.

Nelson’s Auspicious Meeting with an Austrian Count

In 1941, while serving as president of MoMA, Nelson Rockefeller met a man who would become one of his most important collaborators and dearest friends, René d’Harnoncourt. D’Harnoncourt had spent the previous twenty years building a reputation as the go-to expert on indigenous art from the Americas. In 1941, he was at MoMA working as the installer of an exhibit titled Indian Art in the United States.

Born to an aristocratic Austrian family and educated as a chemist, d’Harnoncourt’s life of privilege was cut short with the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1924. Shortly thereafter, d’Harnoncourt immigrated to Mexico City, where he made a living as an illustrator for tourists and local businesses. He soon fell into a social and professional circle of Mexican modernists and began working as a dealer of Mexican art.

After organizing the first commercial show for three of the great Mexican artists of the era; Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Jose Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) and Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991), an American ambassador asked d’Harnoncourt to organize a celebration of Mexican art — both modern and indigenous –at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1930. The show would continue on a 14-city tour, and foster more opportunities for him to grow as an expert, pundit, and lecturer on the subject in the United States. Eventually, this would lead to an invitation to MoMA, his introduction to Rockefeller, and his role as trusted advisor and collaborator regarding Nelson’s collection of indigenous art.

Staffing a New Kind of Museum

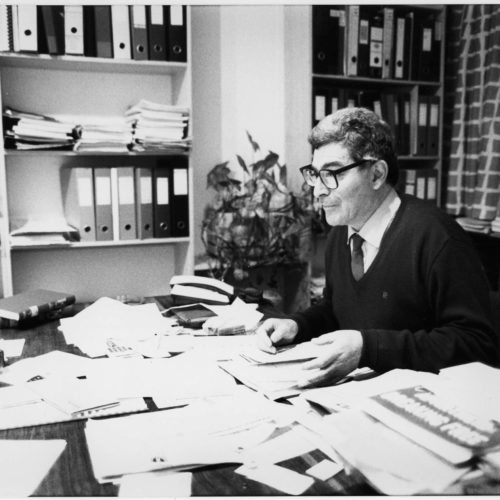

To staff Nelson Rockefeller’s new museum, René D’Harnoncourt–by then the director of MoMA– recommended art historian and professor Robert Goldwater as the Museum of Primitive Art’s first director.

Robert Goldwater’s 1938 book, Primitivism in Modern Painting, was a groundbreaking work that focused on the influence of indigenous art on early 20th century artists. Crucially, it also mapped the course of the West’s interaction with and scholarship of primitive art, from its presentation in cabinets of curiosity to the natural history museums to which it was still relegated. Goldwater understood the distinction between primitivism as an artistic method versus the indigenous artwork being created without western influence. This made him a qualified steward for the new museum.

While Goldwater was a traditional choice, such an unconventional museum would require unconventional staff.

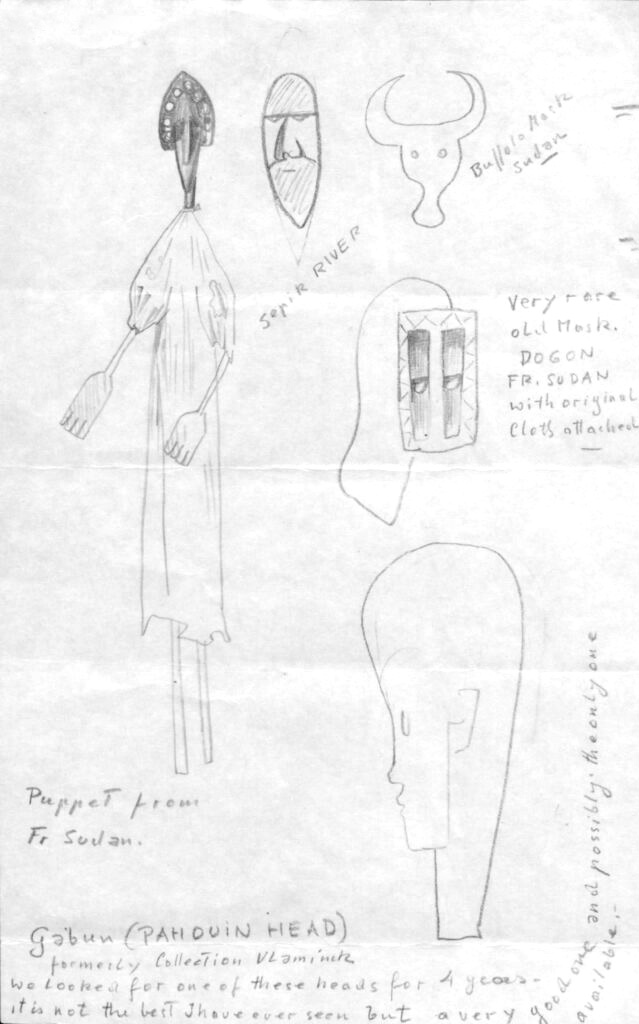

The Museum of Primitive Art’s interpretive philosophy attracted staff with less traditional paths to the museum careers. British journalist and editor Douglas Newton joined the team as assistant curator. Like d’Harnoncourt, Newton’s expertise in indigenous art — particularly of the Pacific — was self-taught. In fact, he had read Goldwater’s book as a teenager and had begun a small collection of his own.

Through a chance meeting in London with the head of MoMA’s International program, Newton learned that Nelson Rockefeller was starting a museum of primitive art and was looking for staff. After meetings with both d’Harnoncourt and Goldwater, Newton was brought on as an assistant curator of the Museum of Primitive Art to manage what d’Harnoncourt could not, due to his responsibilities at MoMA.

Douglas Newton would eventually become a full curator at the Museum of Primitive Art in 1960.

Douglas Newton Expands the Collection

Newton was responsible for acquiring many of the new pieces for the collection in its early years. He followed d’Harnoncourt’s belief that quality was more important than quantity. It would be the mission of the Museum of Primitive Art to collect and display the best examples of art from each era and culture. Both Goldwater and d’Harnoncourt would visit galleries and speak with dealers, a task Nelson Rockefeller loathed. Rockefeller had always felt pressure to purchase something due to his name and reputation, which had led to “loads of junk” clogging up his collection, according to Newton.

While Rockefeller delegated exhibitions to Newton, he was still deeply involved in the acquisitions process:

Everybody thinks he sort of rubber-stamped what we wanted but he didn’t at all. He was very definite in his ideas about what he wanted and if he liked it he wanted it, if he didn’t like it he didn’t want it, no matter what you said.

Douglas Newton, 1995Oral History Project interview with Douglas Newton, February 20, March 3, March 29, 1995, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

What’s in a Name? “Indigenous” versus “Primitive”

The Museum of Primitive Art had space, funding, staff, and a large collection to open to the public. And yet, its first major hurdle was simply finding a name.

When New York State Board of Regents granted the museum charter in December 1954, the team had chosen to call it “The Museum of Indigenous Art.” Regrettably, the term “indigenous” was not as widely used or publicly understood in the 1950s as it is today. At that time, some confused it with the word “indigent,” a term frequently used at midcentury to refer to the poor.

“[The term “indigenous”] doesn’t seem to convey anything to anybody except a few professionals,” Nelson lamented in a letter to anthropologist William Kelly Simpson. “And we are getting a large amount of correspondence addressed to our museum which the writers have confused with Mrs. Vanderbilt Webb’s new Museum of Contemporary Crafts!”Nelson Rockefeller to William Kelly Simpson, November 7th, 1956. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – General, 1956-1972; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center;

After conversations with other experts in the field and members of the museum’s board, Nelson Rockefeller ultimately decided to change the name of his new museum. He adopted the more commonly understood term “primitive,” with the caveat that each museum publication provide an explanation of the museum’s definition of the word. Rockefeller remained uneasy with the term, often preceding it with “so-called” in interviews.

Redefining “Primitive” Art: The Press Reviews the Museum of Primitive Art

After the Museum of Primitive Art’s opening in 1957, the New York press was quick to compare the art pieces with trends in modern art — trends likely familiar to the art-appreciating public:

At least two of the sculpted figures in the new exhibition at the Museum of Primitive Art[…] are not unlike some contemporary primitive-style western sculpture

L. E. Levick, Journal AmericanMuseums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Publicity, Lobsenz & Co., 1958-1961; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

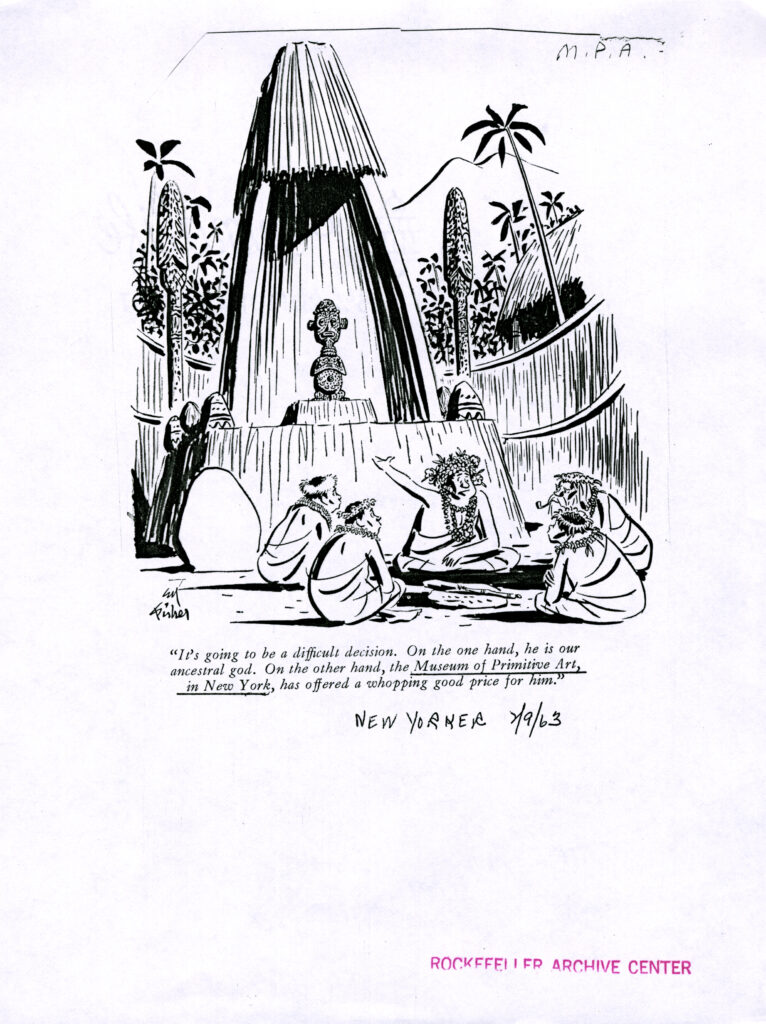

To encourage a perception of the collection as legitimate art, Rockefeller hired public relations firm Lobsenz and Company to promote the museum and track how it was covered in the press.

If the museum of Primitive Art was hoping to redefine the term “primitive,” the press did not immediately catch on. Some coverage of the museum reinforced the implication that “primitive” meant unsophisticated, uncivilized, or of another time:

The humbling message of a good piece of primitive art is that some long-ago savage possessed sensibilities and skills that a modern artist, making art instead of magic, can top only at his best.

“Art: Collector’s Primitive” Time, December 1960Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Publicity, Lobsenz & Co., 1958-1961; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

To counter this perception of the non-Western art they appreciated, the Museum of Primitive Art curators did some publicity of their own. In radio interviews promoting the museum, the team worked hard to challenge the misconceptions and prejudices regarding non-Western art. They emphasized their definition as work done by indigenous peoples without the influence of a traditional Western art instruction.

A lot of the stuff that has been made very recently, within the last few years even, but we still call it primitive as long as it’s not been influenced by European art styles.

Douglas Newton, “Newton of Primitive Art Museum Interviewed” April 6, 1960. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Publicity, Lobsenz & Co., 1958-1961; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers, Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

While interviewers often fixated on the “strangeness” of the art’s spiritual or religious applications. Goldwater and Newton were quick to point out that religious/spiritual objects weren’t unusual in an art museum. Art museums were full of reliquaries, illuminated Bibles, and representations of the gods and funerary practices of ancient Egypt and Greece.

After all, Greek art was primarily a religious art. So was the art of the Middle Ages in Europe and of the Renaissance in Europe. So that primitive art is not different in this respect; it is connected, as you say, with magic, with ritual, with religion, with ceremony to a very large extent.

Robert Goldwater, “Interviews Primitive Art Museum Director” Ruth Hill, City Reporter. April 7, 1960 Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Publicity, Lobsenz & Co., 1958-1961; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers, Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

The Museum of Primitive Art’s prized ivory pendant mask from Benin was sculpted in the 16th century—the same century which saw the High Renaissance in Europe. Incidentally, the price paid for this mask was the highest ever for an example of primitive art. Robert Goldwater touted it as having the potential of becoming MPA’s masterpiece, akin to the Louvre’s Mona Lisa or the MoMA’s Sleeping Gypsy.

I think that as one goes to view the objects, one will recognize, as you say, the sophistication that exists.

Nelson Rockefeller, Press Conference, May 9th, 1969. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – General, 1956-1972; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

Michael Rockefeller: Aspiring Anthropologist

Nelson Rockefeller was not the only member of the family fascinated with indigenous art by the late 1950s. Michael Rockefeller, his college-aged son, was an aspiring anthropologist as well as a member of the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Primitive Art. Douglas Newton believed that Nelson saw Michael as his successor at the institution.

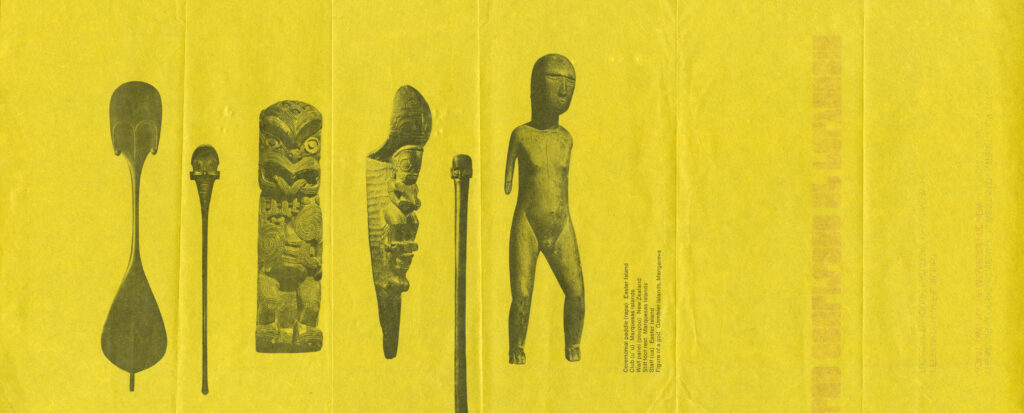

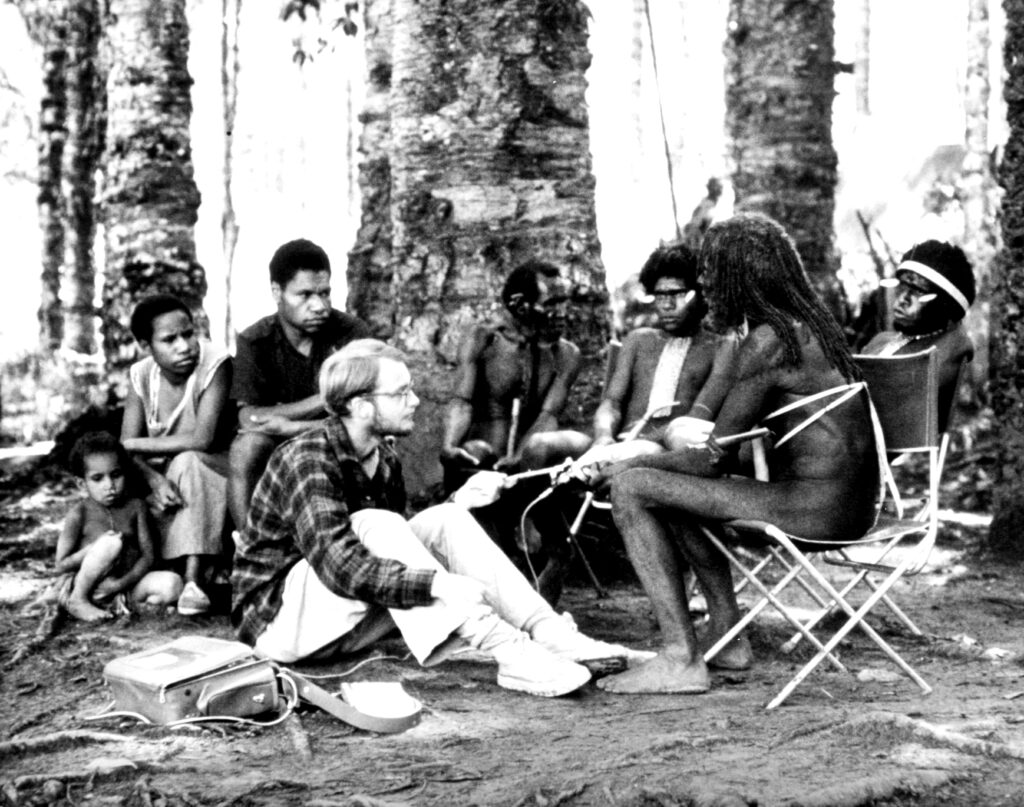

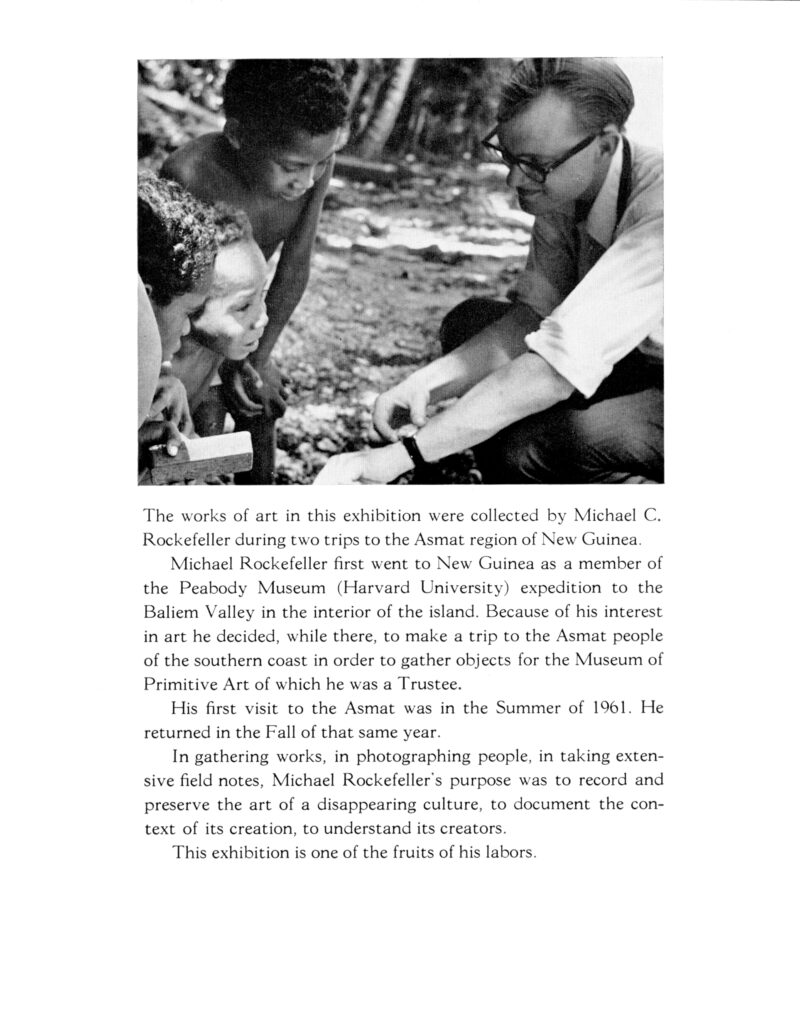

After Harvard and a brief stint in the army, 23-year-old Michael Rockefeller began his journey towards a career in anthropology. In 1961, he set out for Dutch New Guinea to work as a sound recordist on a documentary film expedition for the Harvard Peabody Museum. Titled Dead Birds, the film captured the everyday lives of the Dani of Baliem Valley.

For several centuries the Dutch had colonized this remote part of what is now Indonesia. The region was populated by native peoples such as the Dani and the Asmat in the Southern Lowlands. The tribes of these regions shared an unusual cosmology about the cycle of life and death, and practiced ritualistic headhunting and at times, cannibalism. They had remained relatively isolated until the early 20th century, and used stone rather than metal tools.

While on assignment living alongside the Dani, Michael and a companion traveled to the Southern Lowlands to study the Asmat. He grew fascinated with Asmat woodcarvings, observing how the Asmat were far more influenced by Western culture than the Dani:

The Asmat is filled with a kind of tragedy. For many of the villages have reached that point where they are beginning to doubt the worth of their own culture and crave things Western. […] Nonetheless, the Asmat like every other corner of the world is being sucked into a world economy and a world culture which insists on economic plenty in the western sense as a primary ideal…

Michael Rockefeller’s field notes, 1961. The Asmat of New Guinea: The Journal of Michael Clark Rockefeller. New York Graphic Society, 1961

The Asmat carvings that fascinated Michael were not made to last. Instead, they were meant to decompose and return to the earth once they’d served their ceremonial purpose. Combined with what he predicted to be the potential loss of these carving traditions, Michael recognized the opportunity to preserve them at the Museum of Primitive Art.

In November 1961, Michael Rockefeller returned to the Asmat region shortly after the Peabody expedition. This time, he was there specifically to collect Asmat artwork for his father’s museum. Tragically, a wave capsized the small boat he had been using to traverse the dangerous waters around the region. He and Dutch anthropologist René Wassing floated out at sea for about a day, before Michael tied two gas tanks to his waist and attempted to swim to shore for help. René was rescued the following day, but Michael was never seen again. Stolley, Richard B. “So Bad Even the Bloody Trees Can’t Stand Up” LIFE Magazine, December 1st 1961

Michael Rockefeller’s Asmat Art in Midtown Manhattan

Mike’s hope was that through his pictures and collection he could preserve some part of the old culture before it was lost.

Sam Putnam, a Peabody colleague and close friend to Michael Rockefeller in a letter to Nelson Rockefeller, March 7, 1962. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Asmat Art Exhibitions, also re book, 1962-1971; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers, Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

Michael Rockefeller’s disappearance was followed by a lengthy but ultimately unsuccessful search and rescue mission. Shortly thereafter, plans were set in motion to retrieve the items he had collected in Dutch New Guinea and mount an exhibition in his memory, as well as to publish a book of his photographs and field journals. In January 1962, 400 items — Asmat shields, spears, drums, and eight ancestral Bis poles — were loaded on to a Dutch freighter and began their journey to New York.

The 54th Street townhouse was bursting at the seams with the Museum of Primitive Art’s now 3,500-piece permanent collection, library and offices. It simply couldn’t accommodate the scale of the Asmat carvings. The Bis poles, carved from massive sago palms and arguably the most impressive of Michael’s acquisitions, each stood nearly twenty feet (six meters) tall.

In March of 1962, René d’Harnoncourt delivered good news to Nelson Rockefeller:

At the last meeting, the Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art asked me to offer the Museum of Primitive Art the space east of our formal garden for the proposed exhibition of the primitive sculpture found by Michael in New Guinea. I need not tell you that I myself am most anxious to help with the layout and planning of this exhibition. I have seen much of the photographic material and believe that an exhibition could be very beautiful and will add something new to our knowledge of primitive art.

René d’Harnoncourt to Nelson Rockefeller, March 21 1962. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – General, 1956-1972; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers, Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

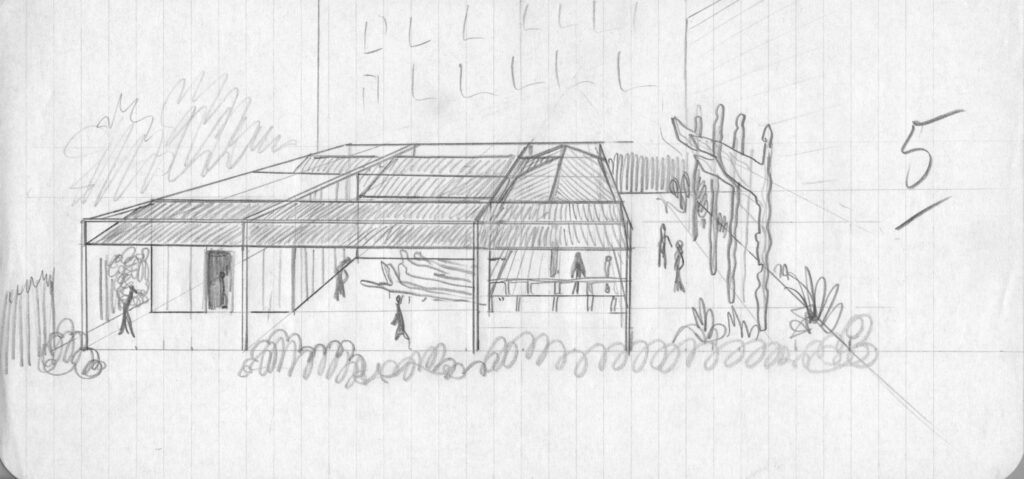

Planning the Indigenous Art Exhibition at MoMA

D’Harnoncourt, Newton and Goldwater set to work planning the exhibition, with the help of MoMA’s Director of the Department of Architecture and Design, Arthur Drexler. Drexler designed an outdoor pavilion to house as many of the items as possible, which included 400 works of art as well as Michael’s evocative photography. D’Harnoncourt designed the exhibit to resemble the inside of an Asmat home, complete with dirt floors.

The Bis poles would be the “dramatic climax of the exhibition,” but not without some weather-proofing.

Nelson Rockefeller did not see the art Michael had collected until the press preview on day before the show opened.

The press release for the MoMA exhibition emphasized the speed with which this art was being lost to time. “Soon, this great tradition of art will disappear under the impact of modern civilization, and with it a small but bright fact of human experience, the Asmat culture, will belong to the past.” Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Asmat Art Exhibitions, also re book, 1962-1971; Nelson A. Rockefeller papers; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers, Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center

The Museum of Primitive Art Finds a New Home Uptown

While the Museum of Primitive art was well-reviewed and relatively successful, it continued to suffer from logistical challenges. As a niche collection type, it did not receive the foot traffic of institutions with more well-known artists and works. Nelson’s political career was becoming increasingly expensive, and the museum’s $300,000 annual budget was becoming difficult to justify.

Furthermore, regardless of the size of the objects from West Papua, the 54th Street townhouse could only display about ten percent of the permanent collection at any one time. The MPA ameliorated this by lending out pieces of the collection to other institutions. Still, museum leadership and curators longed for more space and the legitimacy afforded by a larger cultural institution.

Towards the late 1960s, Rockefeller and d’Harnoncourt decided to attempt a collaboration with The Metropolitan Museum of Art once again. Leadership had changed several times since Herbert Winlock had balked at Nelson’s initial idea. The Met was now led by the brash and business-savvy Thomas Hoving.

In his short time at the museum, Hoving had secured some of The Met’s most notable acquisitions. He had won the nationwide bid to house the Temple of Dendur, which had been a thank-you gift from the Egyptian government to the United States. Hoving had also cinched the entire 2,600-piece private collection of European art from American investment banker Robert Lehman. Both achievements meant fundraising for major building projects, further expanding The Metropolitan Museum of Art to house its ever growing permanent collection.

The Met and Museum of Primitive Art Collaboration

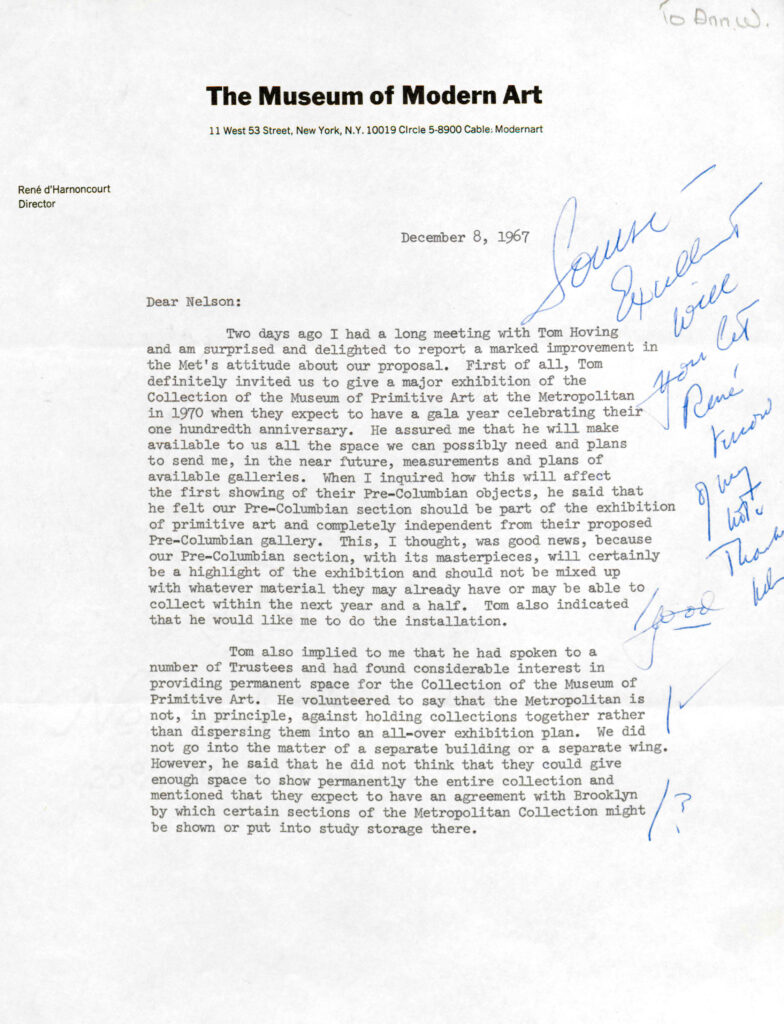

Accounts differ about who courted whom in the eventual collaboration between The Met and the Museum of Primitive Art. What is certain is that conversations began in the late 1960s among Nelson Rockefeller, René d’Harnoncourt and Thomas Hoving to plan a Museum of Primitive Art exhibit at The Met in 1970, on the occasion of the museum’s centennial celebration. In a letter to Nelson Rockefeller, d’Harnoncourt shared that in addition to the exhibit, there had been strong interest from The Met’s Board of Trustees to give the Museum of Primitive Art a permanent home amidst their collections.

(Tragically, René d’Harnoncourt was killed by a drunk driver in August of 1968 while out for a walk on Long Island. He would not live to see the fruits of his labor the following year.)

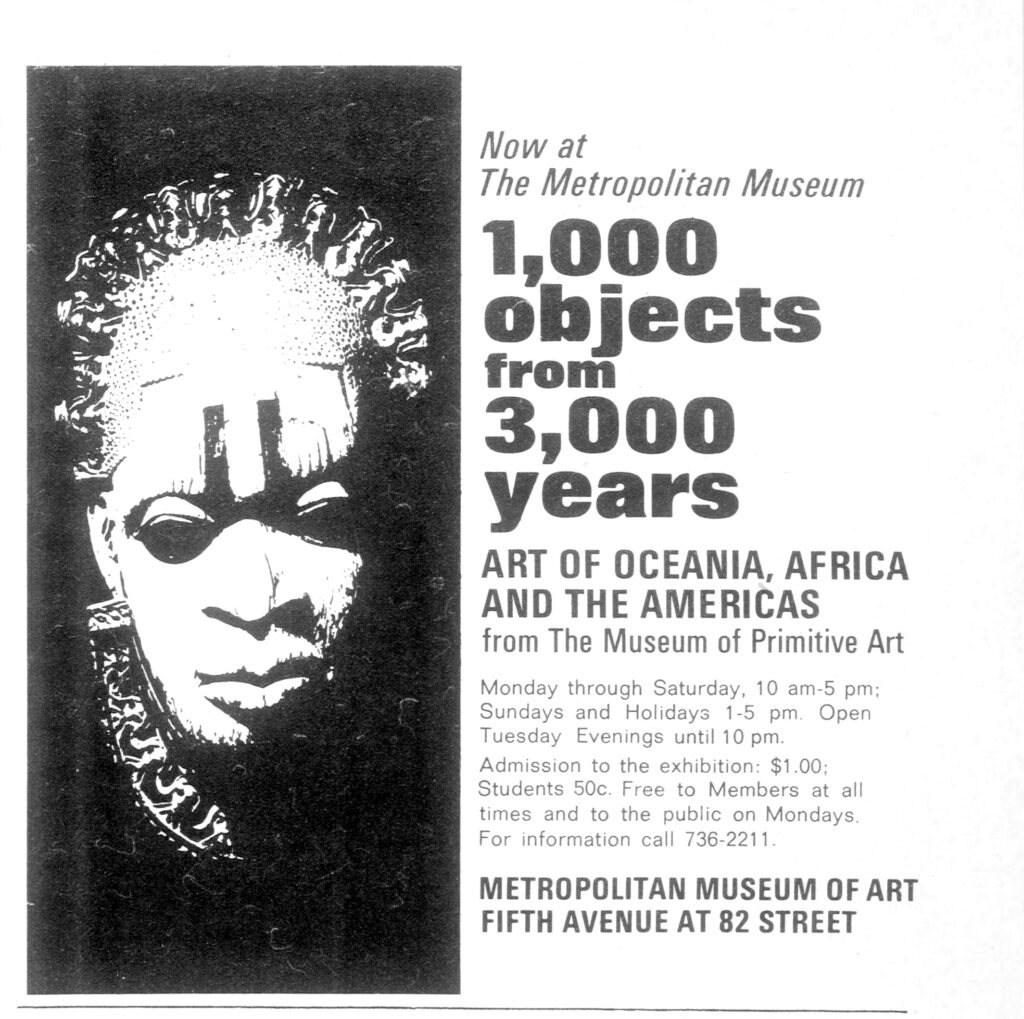

In fact, The Met exhibition came together earlier than expected, opening in May 1969. Rockefeller actually had three concurrent exhibitions of his personal art collection: the indigenous art exhibition at The Met, several modern paintings and sculptures at MoMA, and an exhibit highlighting his collection of Mexican folk art at the Museum of Primitive Art itself. Press coverage compared Nelson Rockefeller to the Medicis, the great Italian patrons of the arts.

At the opening reception for The Met exhibition, Rockefeller recalled his long-ago disagreement with Herbert Winlock and then announced the merging of the Museum of Primitive Art with The Met:

I forgive the old boy and the Met. And to prove it, I want to let you know that arrangements have just been concluded—the ‘treaties’ are about to be signed—to transfer my Museum of Primitive Art, lock stock and barrel, including the works of art and curators and staff—everything—to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The two great institutions will as of this moment be merged and become the greatest single encyclopedia of art in the world.

Nelson Rockefeller, 1969 Making the Mummies Dance: Inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Thomas Hoving, Simon and Schuster, 1993.

Nelson Rockefeller explained that the collection would be housed in a brand new wing, named in memory of his son, Michael. The collection would form the basis of an entirely new curatorial department.

Indigenous, “Primitive,” and Non-Western Art Today

The 1969 Met exhibition was a great success. Within the first month, over 42,000 people visited, with a daily average attendance three times that of the Museum of Primitive Art. It would take over a decade to construct the new wing and to transfer and install the exhibits.

Nelson Rockefeller died in 1979 and so he did not live to see the February 1982 opening of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing. Reviews poured in, noting the potential shifts in interpretation that could occur at other art museums. Academics of indigenous art were optimistic at how this endorsement from The Met would cause other art museums to follow suit:

Clearly the opening of this wing is a major art event that will reverberate through time and space. Boston may realize that these arts matter, and LACMA may move them up from the basement, to cite two possibilities across the country from one another. Paris and Brussels will notice what has happened in New York, and the Museum of Mankind in London may, we hope, decide to put at least a segment of its unique collection on permanent view once more.

Herbert M. Cole, African Arts“The New Michael C. Rockefeller Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” African Arts, Feb 1982 Vol 15, No 2 pp.28-37

In the decades since the opening of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, attitudes and approaches to interpretation have shifted yet again. The Museum of Primitive Art sought to let non-Western art stand on its own, without the aide of ethnographic dioramas or allusions to “uncivilized,” “unsophisticated” cultures. In decades since, museum interpretation has evolved towards more decolonized frameworks, which reassess how indigenous cultures are interpreted in museums. Cultural context is re-applied, however conscious effort is made to include the judgment and guidance of those cultures being represented. The Met’s recent renovation continues that trajectory towards inclusive, equitable exhibits and publications.

A Nuanced Debate

Even today, some advocates will say that that the objects should be repatriated to the countries and cultures that produced them. But the debate is complicated and nuanced; some professionals within the field argue that it is instead advantageous to build strong relationships with the cultures represented in order to protect and exhibit the artwork properly and respectfully.

Additionally, the rise in the art’s popularity and value has contributed to a rise in looting and smuggling, requiring some countries to devote resources to protect archaeological sites and enforce harsh restrictions on what can legally leave the country.

Surely, the debate on indigenous art in museums and how it is interpreted is far from over. The decision regarding what is art and, importantly, who makes that classification continues to be contested.

If this was done the right way, perhaps some westerner would realize that ‘primitive’ man was not an animal or a child, but a full grown human being with feelings and beliefs that went just as deep as our own.

Sam Putnam to Nelson Rockefeller, March 7, 1962. Museums – Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street – Asmat Art Exhibitions, also re book, 1962-1971; Nelson A. Rockefeller personal papers, Projects, Series L; Rockefeller Archive Center