American Choreographers in the 1980s

American choreographers found themselves in a new situation in the 1980s. By the middle of the decade, American dance was at a peak. Audiences at home and abroad had increased significantly. Training opportunities for dancers were better and more numerous. And public and private funding was greater than ever. Regional as well as national dance companies now commanded attention and world-wide acclaim.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s program of support for “single-choreographer” dance companies in the mid-1980s was successful, albeit short-lived. Its significance lies in the insight it offers into a distinct moment of funder-grantee collaboration. And, even after the program ended, the Foundation continued funding national and international dance company tours through the 1990s.

Basically, dance companies were of two types in the 1980s – and this remains true today. The first was the “repertory” dance company, which presents the work of multiple choreographers in a given season. The other was the “single-choreographer” dance company, which exists to show and advance the innovative work of just one creative choreographic artist. Although the two categories reflect differences in company size, type(s) of offerings, and budget level, they have one thing in common. They both have a continuous need to create new works.

The Rockefeller Foundation and the National Choreography Project

Officers at the Rockefeller Foundation understood this fact. They observed that, if the dance field was to continue developing, choreographers must be given increased opportunities for creativity. In 1983, the Rockefeller Foundation began addressing this problem through the National Choreography Project (NCP). This program was launched in cooperation with the National Endowment for the Arts and the Exxon Corporation, and administered by Dance Works.

The NCP provided “repertory” dance companies with financial assistance to offer residencies to choreographers previously unfamiliar to them. This funding aimed to stimulate “the creation of new works that challenge both dancers and audiences, and enrich companies’ stylistic diversity.”“Introduction to Choreography Items,” April 2, 1986, Folder 331, Box 55, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC

Support Broadens for American Dance

Two years later, in 1985, a small band of Rockefeller Foundation officers proposed a complementary dance assistance program. They noted that “the Foundation-supported NCP is exclusively concerned with meeting the need for new works on the part of repertory companies.”“Program of Support for Single-Choreographer Dance Companies,” circa 1986, Folder 331, Box 55, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC “Single-choreographer” dance companies remained ineligible. To resolve this disparity, a new program was recommended to complement the NCP by making awards to companies headed by outstanding choreographers.

Together, these two programs represented, from the Foundation’s viewpoint, “balanced support for the creative person in dance.”“Introduction to Choreography Items,” April 2, 1986, Folder 331, Box 55, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC

American Choreographers and the Rise of “Single-Choreographer” Companies

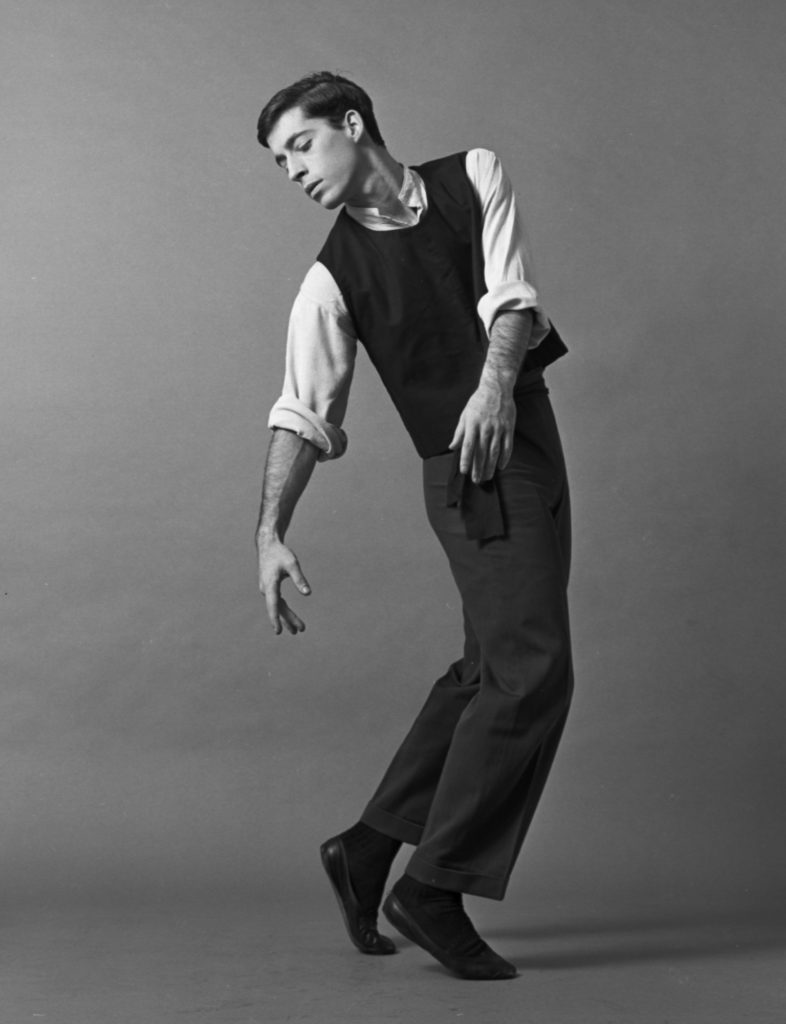

Indeed, by the mid-1980s, the high-regard for American dance was largely dependent upon a limited number of (mainly modern) dance creators. Those who helmed their own “single-choreographer” companies included Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Twyla Tharp, Alvin Ailey, Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, and Paul Taylor, to name a few. Eliot Feld, helming his own neoclassical ballet troupe, remained one of the few ballet voices not working within the customary “repertory” company paradigm. With ingenuity and skill, these inventive choreographers redefined the very language of movement and syntax of formal structure.

They also shared similar modes of working. Most notably, they all created within their own company of dancers. Their creative process, however, also raised the necessity of rehearsal pay for these dancers. Choreography must be done in the presence of — and using the bodies of — dancers skilled in their particular style. This creative method differed, for example, from the writers who received funds from the Foundation’s “Playwright-in-Residence” program. At least initially, playwriting could be a solo endeavor. In contrast, dance could not be made in solitude.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s proposed grant program for the “single-choreographer” aimed to assist dance-makers who worked with their own dancers in maintaining the much-needed environment for experimentation.

Foundation Staff Call on American Choreographers

By the time Rockefeller Foundation officers presented their ideas for this new program to the Foundation’s trustees in spring 1986, a great deal of research had gone into the proposal. The entire concept, in fact, had been fostered in alliance with a small group of prominent New York choreographers. Evidence of this is found in the Foundation’s vast archives thanks to the existence of two audio cassettes bearing the simple annotation: “Choreographers Meeting, November 6, 1985.”

As the unique recordings make known, three choreographers — Paul Taylor (modern dance), Eliot Feld (ballet), and Trisha Brown (post-modern dance) — were invited to gather at a Foundation office for sandwiches and conversation. A tape recorder was placed on the table in front of the guests and the entire 165-minute discussion that commenced was captured on tape.

Upon first seeing the machine, Brown whispered, “What’s that?”

“Oh, we are recording this,” explained Howard Klein, Rockefeller Foundation Deputy Director for Arts and Humanities.

“Should we call Nixon?” was Brown’s joking reply.“Choreographers Meeting, November 6, 1985,” AV 9995 (Audio), Folder 334, Box 56, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC

Philanthropy and Choreographers in Conversation

The conversation that followed was informative, enlightening, and candid. The three legendary choreographers openly shared their personal philosophies and dance ideologies. But it wasn’t all about the art: Rockefeller Foundation staff had grantmaking work to do, and proceeded with a skilled line of questioning to ascertain what kind of funding would be most effective. Most importantly, they came prepared to listen.

As Klein told his guests: “We are now inviting you into our Foundation apparatus – and it’s a terribly uninteresting thing – but we really need you to help us think through this [grant program]. I don’t think that there is anything you say or suggest that is too ‘far out’ for us to hear. We will be left at the end of the conversation with how to put [the program] together.”“Choreographers Meeting, November 6, 1985,” AV 9995 (Audio), Folder 334, Box 56, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC

Sketching Out a Dance Grant Program

For nearly three hours, a free-flowing discussion emerged. What should the grant criteria be? Who should be funded? What is the selection process? Who should select? Can a selector overcome personal bias? Is selection subjective — or can it be objective? How much should the funding amount be? Is it better to offer several small grants or a few large grants?

Questions led to other questions. All yielded a multitude of spontaneous and honest answers.

The Choreographers’ Artistic Perspectives

Naturally, the distinctive personalities of each choreographer came in to play, as well. Trisha Brown, bright and agreeable, meditated on the difficulty of career continuity in dance. Eliot Feld, brasher and more opinionated, wondered if there was a crisis in ballet choreography given the recent death of George Balanchine. And with worldly ease, the genteel Paul Taylor expounded on inherent problems when dance was crafted via the grant application process, calling such a process “a weight” to choreographers.

“Artists should not be affected by administration folderol,” Taylor mused. “We must be free to let our imaginations go where they have to. And when we try to fit ourselves into [a grant] application mold, well, that is not ideal. It’s a [financial] help, but it’s not ideal…it is dangerous.”“Choreographers Meeting, November 6, 1985,” AV 9995 (Audio), Folder 334, Box 56, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC

We must be free to let our imaginations go where they have to.

Paul Taylor, 1985

The Final Awards: Mark Morris, Trisha Brown, Twyla Tharp and other American Choreographers

The Foundation officers came away from the discussion with a clearer understanding of the choreographers’ working methods and need for artistic freedom. Ultimately, the Foundation appropriated the sum of $210,000 “for allocation by the officers for a program of support to enable selected ‘single-choreographer’ dance companies to create new works.”“Introduction to Choreography Items,” April 2, 1986, Folder 331, Box 55, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC Those receiving funds between 1987-1988 included Brown and Feld, along with Twyla Tharp, Meredith Monk, Laura Dean, David Gordon, Mark Morris, and Steve Paxton.“Allocations Approved Under RF 86006,” 1986, Folder 331, Box 55, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC

The awards showcased a wonderfully gender-mixed sampling of contemporary dance voices. Some new, some familiar. But all bursting with fresh ideas. Awards ranged from $35,000 for four of the more experienced choreographers to $15,000 provided to the others.

Grants to American Choreographers Enable Dance to Innovate

Through the Rockefeller Foundation funding (as well as further financial support from other institutions), the 1987-88 dance season proved fruitful. New works flourished.

Audiences witnessed the premiere of Trisha Brown’s “Newark,” with decor and sound concept by Donald Judd. Eliot Feld stepped back into a purely classical ballet mode with his well-received “A Dance for Two.”

Mark Morris offered his “L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato,” and the piece was later hailed as his masterwork. Twenty-five years after the work’s premier, The New York Times noted: “Masterpiece isn’t a word to be thrown around lightly, but there’s no denying that Mark Morris’s “L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato” is thrillingly that.”Gia Kourlas, “On TV, That Thing With Feathers” The New York Times, March 21, 2015.

Spotlighting the peak popularity of American dance, David Gordon created his “Made in the U.S.A.” This new work featured Mikhail Baryshnikov (originally from the Soviet Union) and Valda Setterfield (from England) who come from different countries and traditions with one common goal: to dance in America.

The work was ultimately filmed for the Dance in America television series, and Gordon received a Primetime Emmy Award for the program.

“Miraculous Accidents”

In retrospect, the 1987-88 season was stunningly creative. Philanthropic funding aided this innovation. As did the Rockefeller Foundation’s bold approach in allowing the creative person in dance an active voice during the grant-making process. In doing so, the rehearsal rooms of several American choreographers remained, as Paul Taylor expressed at that afternoon lunch, a revered place “to let miraculous accidents happen.”“Choreographers Meeting, November 6, 1985,” AV 9995 (Audio), Folder 334, Box 56, projects, SG 1.18 (A92), FA469, Rockefeller Foundation records, RAC

Further Reading

- Emily Hawk, “Granting Movement: The Impact of Cultural Philanthropy on African American Concert Dance in the 1960s and 1970s.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2025.