Long before there were “genius” awards, the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) struggled with how to identify and encourage “creativity” in the arts and culture. While artistic expression clearly benefited humanity, as RF Associate Director for the Humanities John Marshall put it in 1950, there was no way of knowing “what the arts contribute to human wellbeing.” Their importance “cannot be asserted on the basis of objective evidence.”John Marshall, “The Arts in Humanities Program,” 17 January 1950, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 3.1, Series 911, (Report Pro-20a), Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Foundation had a long history of funding science and health, and its concern here with measurability and objectivity may reflect its discomfort working within the looser realm of the arts. By launching a fellowship program in creative writing in the 1960s, in the era of civil rights and the emerging Black Power movement, the Foundation would take on further discomfort as it attempted to parse what qualities might ensure that the new writing supported by the Foundation would rise above contemporary styles, political concerns, or identity politics.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s Literary Grants in the 1960s

From the mid-1940s, the Foundation had supported creative writing through a small program of fellowships and grants to literary magazines and writing centers, but it rarely made grants to individual artists. In September 1963, in a major programmatic reorganization, the Rockefeller Foundation made “Cultural Development” part of its blueprint, Plans for the Future. The Foundation created an arts program in the fall of 1964, and in October it launched an experimental program in creative writing, also called “Imaginative Writing and Literary Scholarship.”Records of the RF’s support for creative writing and the Imaginative Writing program are found in the Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911 (Humanities) and Series 925 (Arts), with earlier materials found in RG 3.1, Series 911. Project files for individual grant recipients under the program are generally found in RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The trustees saw writing as “the missing factor in most attempts to do something in the cultural field.”Kenneth W. Thompson memo, Main Currents of Trustees’ Reaction to “Cultural Development,” 27 December 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 925, Rockefeller Archive Center.Missing, partly because the Rockefeller Foundation was uncertain whether or how to fund the individual writer. The RF had always funded individuals through their institutions, for better oversight and reach. Its storied program of fellowships for scientists had been making grants to individuals since 1917, and laboratory science is always done within an institutional context. But writing was a solitary process, which did not always benefit from institutional ties. Writers—and other creative artists—needed “full freedom” to do their work. Freedom from material needs or the demands of a job; freedom for travel or training or inspiration; freedom from particular expectations or the need to produce a specific work.John Marshall, The Arts in Humanities Program, statement on Assistance for Original Work, 30 January 1950, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.1, Series 911, (Report Pro-20a), Rockefeller Archive Center.

Why Fund Writers?

There was also the “why.” What was the good of literature and why should the Rockefeller Foundation fund writers? For John Marshall, the goal was “the realization of humane values in individuals and in society.”John Marshall, statement on Assistance for Original Work, 30 January 1950, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.1, Series 911, (Report Pro-20a), Rockefeller Archive Center.Still, when he met with novelist Saul Bellow in January 1951, Marshall talked frankly about the “perplexities” Humanities officers faced in considering aid for creative writing. Bellow agreed to write up his view of the “novelist’s responsibility.”John Marshall notes on interview with Saul Bellow, 9 January 1951, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center. Bellow’s essay—a five-page “gem”—pointed to “the stature of characters” as the “great issue” in fiction. In Bellow’s view, the “contrast of a [character’s] superior reality with daily fact is the peculiar field of the novel.” The novelist’s continuing task is to “attempt to fix a scale of importance” and to rescue “an original human value” from vagaries of style, language, and social facts. Bellow concludes: “I believe in feeling, simply, in vividness.” In modern society, “man is forced to lead a secret life, and it is in that life that the writer must go to find him. He must bring value, restore proportion; he must also give pleasure.”Saul Bellow statement on the responsibility of the novelist, [January 1951], Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R. Gerald Freund termed Bellow’s essay a “gem” in a letter to John Marshall, 31 January 1966, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Creating (Elitist) Selection Standards

Gerald Freund, who headed this new creative writing program, echoed Bellow’s views in a 1968 memo, “Concerning a Philosophy of the Arts Program.” Freund argued that the criteria for support of the creative artist were not a matter of style or the avant-garde. Rather, selection should be based on the “highest standards of integrity and decency.” What counted was the “artistic intention of seeking truths, of ennobling rather than debasing the human individual and society.”Gerald Freund, “Concerning a Philosophy of the Arts Program, [1968],” pp. 4-5, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 925, Rockefeller Archive Center.The self-conscious, even awkward, struggle of the Foundation staff to come up with a suitable rationale for supporting art, and their belief that high moral purpose would guarantee high quality work, seems old-fashioned (even for that time) and, by today’s standards, naïve at best.

But the Rockefeller Foundation nevertheless sought to implement these “highest standards” in its Imaginative Writing program. According to the program officers, other grantmaking agencies tended to tap “run-of-the-mill” or “lowest-common-denominator” candidates, resulting in programs that were “whimsical” or even “inept.”See Gerald Freund’s memos, 10 and 15 September 1964, and the grant action approving the Imaginative Writing program, 23 October 1964, in the Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.. For the description of other programs as being whimsical and inept, see Freund, Concerning a Philosophy of the Arts Program, [1968], p. 4, RG 3.2, Series 925; and Freund to Joseph E. Black (quoting Robert Penn Warren), 5 January 1968, RG 3.2, Series 911. Saul Bellow quipped that, like Noah’s ark, “the program in Washington has two beasts of every species.” Meeting of the Advisory Committee, 12 December 1966, RG 3.2, series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.In contrast, the RF saw itself as “particularly well suited to direct support of individual creative artists.”Gerald Freund, Concerning a Philosophy of the Arts Program, [1968], p. 4, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 925, Rockefeller Archive Center.Why? It could provide the seed money to spur creativity; it had the flexibility to tailor the techniques of its support to particular needs for training, travel, or experimentation. It could be a “patron” to the arts.On the Rockefeller Foundation as patron, see Kenneth W. Thompson, Main Currents of Trustees’ Reaction to “Cultural Development,” 27 December 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Describing the selection program, Freund concluded that “there is just no getting around the necessity for hard work and high standards, the desirability of great flexibility in designating award amounts and purposes, and, not to be excluded, the intuition of qualified individuals in taking risks.”Freund to Carolyn Kizer, 20 May 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center. Kizer was a poet and the Director of Literary Programs for the newly created National Endowment for the Arts.Who, then, would be tapped as qualified enough to be entrusted with taking the risks of making grants to writers?

The (White, Male) Advisory Committee

At the start of its program, the RF appointed Pulitzer-prize-winning poet Robert Lowell, who hailed from a Boston Brahmin family and attended Harvard and Kenyon College, to be its Consultant in Creative Writing and Literature. Established writers Saul Bellow and Stanley Kunitz joined Lowell to serve as a panel of “discussants, consultants, advisors.”Gerald Freund meeting with Saul Bellow, Stanley Kunitz, and Robert Lowell, 1 October 1964, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.They would later be joined by Robert Penn Warren, John Hersey, Walker Percy, Mark Smith, Robert Coles, and James Dickey. Black theater director Woodie King, Jr. would join in the program’s final year.

These literature consultants met monthly at first with Foundation officers, and reviewed, debated, and evaluated the submissions. The Rockefeller Foundation wanted a program that was flexible enough to recognize and encourage the young writer with “highest potential,” along with more experienced or senior writers “in need.”Gerald Freund, Creative Writing Program, 15 September 1964, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.A broad-based and regionally (if not culturally or ethnically) diverse group of writers, scholars, editors, and critics served as nominators, and candidates invited to apply were then screened, interviewed, and carefully read.

The advisory committee and program officers drew up a list of nominators, the number of which ranged from 30 to some 150, depending on the year. Grantees from previous years were also asked to nominate new candidates. Some of the nominees (around 35 – 45) were then invited to apply for a grant.Records of advisory committee deliberations are found in the Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.Robert Lowell likened the committee’s work to a “guild system of artists judging artists,” with all that the term implies about access and control.Minutes of Final Literature Committee Meeting, 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.

This deliberative process was deemed, by the internal accounts preserved in the archives, “extraordinarily successful.”Saul Bellow, Memorandum on the Literature Program, 28 May 1969, enclosed in Gerald Freund to Joseph E. Black and J. George Harrar, 9 June 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 3.2, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.Grant recipients in 1966 ranged from a young Cormac McCarthy, then working on his novel Suttree, to Philip Roth, accomplished, but in a period of critical need. Like the hypothetical novelist Bellow had outlined in his “gem,” McCarthy described the aim of his book set in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the early 1950s to be “an understanding of what life here would mean to a person who was totally aware. In a sense, … these characters are the embodiment of a single soul.”Cormac McCarthy grant application, 15 March 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The experimental program in imaginative writing ran for five years (through 1969) and sponsored an exceptional roster of close to one hundred writers and poets. In a period of social, cultural, political, and racial ferment, the committee sought out writers of excellence and promise. However, it seldom interrogated its own notions of what constituted these qualities, or the limitations of its vision. It did look for diversity in age and experience; it looked for regional representation (perhaps as a stand-in for cultural diversity); and it wasn’t afraid to look beyond the ivory towers. Its only stated agenda was an insistence that its nominators be impartial, unbeholden to cliques or groups.

As we shall soon see, adherence to an “impartial” standard was problematic. In fact, whether applicants were beholden to cliques or groups was very much at issue, especially with Black writers.

Of the one hundred writers chosen across five years, ten were Black.

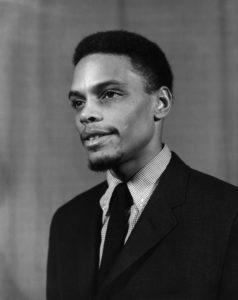

Ronald Milner, “a writer of immense promise”

The young playwright Ronald Milner was chosen in 1965 for a fellowship to work with writers George P. Elliott, on sabbatical at the American Place Theatre, and Harvey Swados at Columbia University. The Imaginative Writing program claims him as its own, though technically Milner’s fellowship, and subsequent writer’s residency at Lincoln University, were funded through different RF grants.Philip W . Bell called Milner “a writer of immense promise” in his memo on Milner and Lincoln University, 27 May 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Ron Milner was an unusual candidate in many regards. Just twenty-six when he was nominated, he was working on a novel, even as he held a succession of jobs to support his young family. Milner had sent a draft of his novel to Allan Seager, a writer often compared to Ernest Hemingway, who was quick to nominate him the first year of the program as “the most promising young writer I have seen in recent years.”Allan Seager to Gerald Freund, 15 February 1965, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 10.1, Series 200E, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Milner’s The Life of the Brothers Brown told of two brothers growing up in Detroit, trying

to force a desirable life for themselves out of the chaos and debris of their slim beginnings: … and out of the looming, surrounding, all-powerful “white” society, seemingly set implacably against them – or so father, mother, uncle, friends, and occurences [sic] suggests to them.

Ronald MilnerOutline for Rockefeller Grant, 19 June 1965, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 10.1, Series 200E, Rockefeller Archive Center.

If Milner’s “style was awkward,” Seager found his work “moving and deeply felt.” Milner (a playwright, after all) had “a real sense for the construction of scenes.” According to Seager, Milner “was not angry in the way James Baldwin is angry. He merely tells his story and wisely depends on the selection of incident to move the reader.” But even as he invoked, and seemingly bought into, the stereotype of the angry Black man, Seager made a poignant plea:

I hope he will receive a grant. It is uphill work for any beginning novelist, but I was appalled when I realized how steep the grade is for a young negro.

Allan SeagerSeager to Gerald Freund, 15 February 1965, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 10.1, Series 200E, Rockefeller Archive Center.

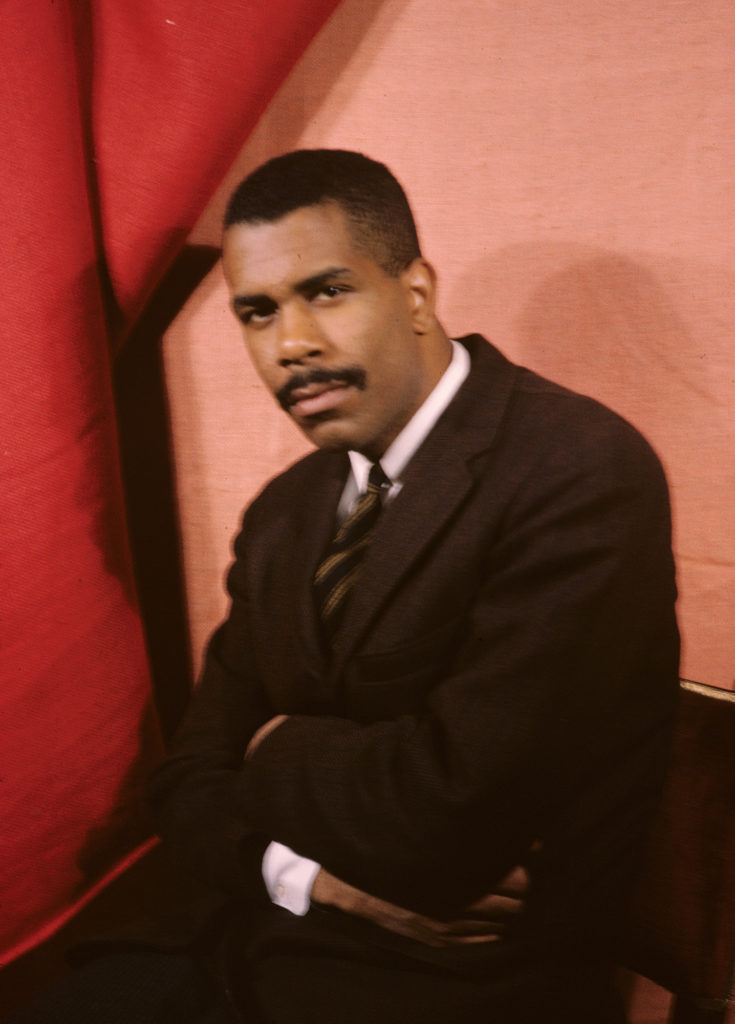

Robert Deane Pharr, a “Black Sinclair Lewis”

In 1966, Robert Deane Pharr received a modest stipend to cover tuition, typing, and research expenses while he worked on his second novel about the tenants of the Bryn Mawr, a notorious single-room-occupancy hotel once owned by Columbia University. A welfare recipient, Pharr worked part time as a waiter at Columbia’s Faculty Club. He came to the Foundation’s attention after he had asked the chairman of the English Department to take a look at his manuscript.

Pharr grew to resent the oft-repeated origin story of his being a waiter: “It looks like they review the book because it was written by a black waiter. It’s things like that that tend to drive a black writer up the wall.”John O’Brien and Raman K. Singh, “Interview with Robert Deane Pharr,” Negro American Literature Forum, 8:3 (Autumn 1974), pp. 244-246. Pharr noted in this same interview that when he first started writing, he had aspired to be a “black Sinclair Lewis.”

For his new novel, S.R.O., Pharr wished “to go back among my characters,” his former neighbors, “and refresh my memory.” He aimed “to tell the story of these people when the welfare worker is not present.” His novel would tell the reality of his characters’ lives, superior or not, in contrast to the daily facts and misapprehensions of social policy and caseworker reports.Robert Deane Pharr work plan, 11 April 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center. See also Gerald Freund’s notes on his meeting with Pharr, 19 April 1966, in the same file.

In evaluating the writing program, the forty-nine-year-old Pharr stressed the psychological value of his award:

For the first time in my life I felt like a writer…. And I was a free man, doing what I knew I had to do.

Robert Deane PharrPharr to Gerald Freund, 21 September 1968, in Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

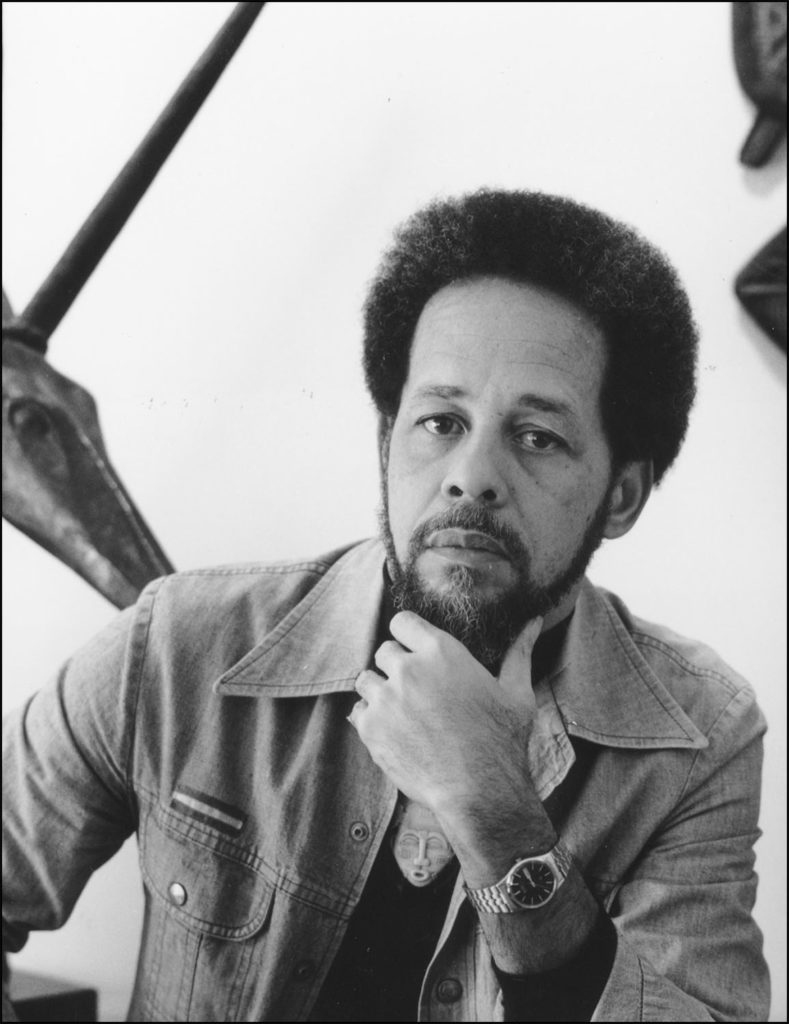

William Melvin Kelley, “leading Black intellectual”

The committee selected William Melvin Kelley for a grant in 1968. Already deemed “a leading young black intellectual,” Kelley had published three novels and a story collection by the time he was thirty. Kelley’s “vividly imaginative” first novel, A Different Drummer, is the story of a southern Black farmer who one day destroys his farm and leaves the state and is soon followed by the state’s entire Black population.MacLeish to Gerald Freund, 10 May 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.Kelley tells the story from the viewpoint of the white neighbors who suddenly find themselves abandoned. “A black man writing about how white people think about black people,” Kelley was always trying to “rescue that original human value” of which Bellow spoke, and thereby make it more inclusive.See Kathryn Schultz, “The Lost Giant of American Literature,” The New Yorker, 29 January 2018. In outlining his plan of work, Kelley explained his wish to study European colonialism and then Africa itself. He described the feeling that Black Americans

…suffer from a certain amnesia of the spirit. What we truly are, as a people, has never been adequately explained to us…. I am trying to find out how African we still are, and just how much of Africa we have lost.

William Melvin KelleyWilliam M. Kelley grant application, 20 April 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Kelly received his award notwithstanding his mentor Archibald MacLeish’s harsh concerns that he was “denying his own nature” in having “picked up the intellectual and literary fashions of the current Negro avant garde.” MacLeish was a well-known poet who had studied at Yale and Harvard universities, three times won the Pulitzer Prize, and served as Librarian of Congress. His rather patronizing recommendation suggests that Black writing was a fad or a posture, not a legitimate endeavor.

What this all comes down to is that if Kelley will stop being a professional Negro and go back to the art of writing which knows no color or other differences, he has, in my opinion, a real future before him.

Archibald MacLeishMacLeish to Freund, 10 May 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Kelley’s grant supported his study of European colonialism in France, and research into African survivals in Jamaica.

During his grant year, Kelley completed his final published novel, Dunfords Travels Everywheres, which has been likened in its use of language to a Black Finnegan’s Wake – it is rewarding, but ultimately very demanding on the reader. Kelley had an ear for language, and his vernacular complements and complicates his allegorical, wonderfully inversive, and timely storytelling. Though Kelley continued to write throughout his life, he published nothing further.

The 1969 Cohort

In 1969, its final year, the Imaginative Writing program tapped seven Black writers for awards: June Meyer Jordan, Carlene Hatcher Polite, James A. McPherson, Clarence L. Cooper, Jr., Ernest J. Gaines, Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, and the South African exile Keorapetse William Kgositsile. The group included poets, essayists, novelists, storytellers, and crime writers, from a wide variety of backgrounds and of equally wide accomplishments.

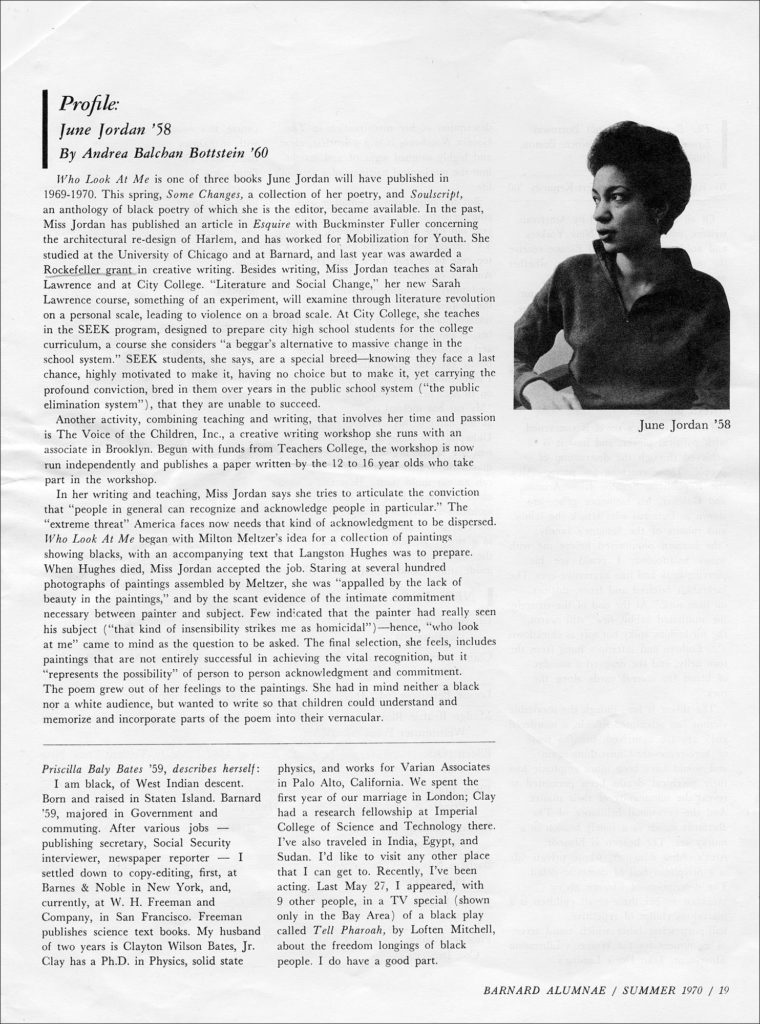

June Jordan, Poet, Teacher, and Activist

…that I may learn, rather than ‘do,’ about the origins of that hatred we all suffer…

June Jordan

June Jordan had two volumes of poetry in press when she received her award. At thirty-two, she had also scripted films, taught college English and writing groups for children, worked with Mobilization for Youth on urban housing, and collaborated with Buckminster Fuller on a plan for redesigning Harlem. For Jordan, the grant would bring “leave from the earning of money” and the prospect of “whole attention and liberated imagination.” It offered the hope, “to participate, successfully, in the new mythmaking we, who are bereft of heroes and motivating ideals, can use to happy, large purpose,” as well as the hope to travel, within America, “that I may learn, rather than ‘do,’ about the origins of that hatred we all suffer, more and more.”June Meyer Jordan grant application, 12 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.Jordan traveled to Mississippi and the Sea Islands of Georgia on her grant. In October 1970 her essay “Mississippi ‘Black Home’” appeared in the New York Times Magazine. Jordan’s illustrated Who Look at Me and her anthology of Black poetry, Soulscript, came out the same year, followed by a young adult novel, His Own Where, in 1971.

In its grant summary, the Rockefeller Foundation noted that Jordan was “black and aware of it,” yet the RF staff felt compelled to emphasize that her poetry had “broader themes and wider appeal.” Millen Brand’s recommendation was more forceful, as well as more accepting of Jordan’s ideological commitments: “her writing is strengthened by close ties with the black community…. Her work is not only creative … it comes from a passionate, vital concern for the world around her.”Grant summary, 23 June 1969, and Millen Brand to Gerald Freund, 14 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

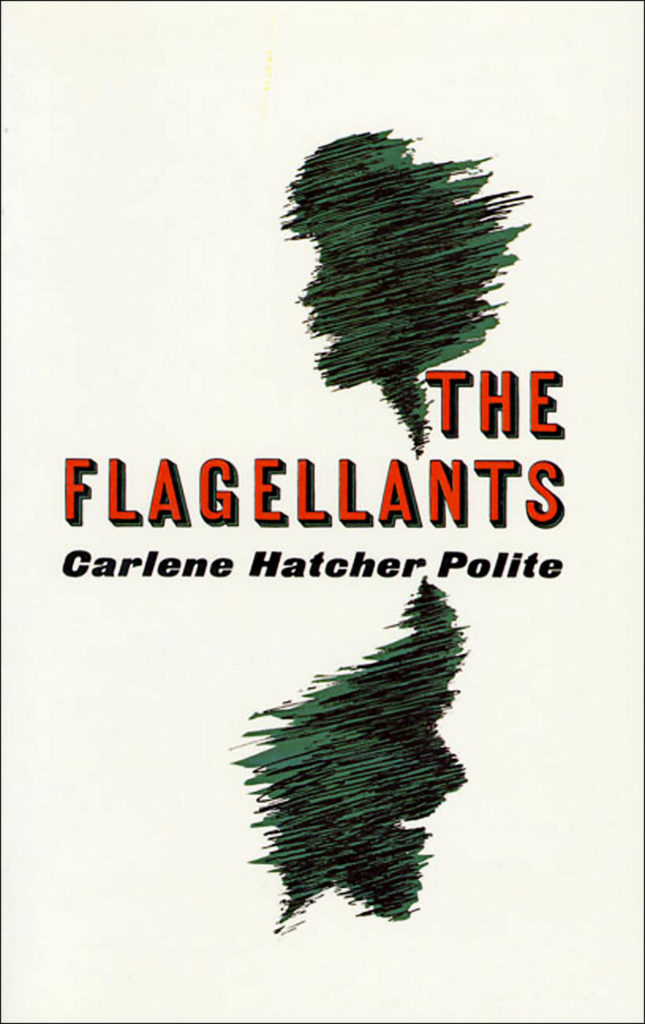

Carlene Hatcher Polite, Activist and Expatriate

Carlene Hatcher Polite was a dancer and an organizer – but above all, she was a writer. She traded a scholarship to Sarah Lawrence to study dance with Martha Graham. Living in Greenwich Village in the 1950s, she returned to Detroit in the early 1960s, where she worked in theater, politics, and the civil rights movement.

In 1964, she moved to Paris where she wrote and published her first novel, The Flagellants, in French. Published in the U.S. in 1967, the short novel told of the volatile relationship of a young Black couple in Greenwich Village in the 1960s. Stanley Kauffmann, who nominated Polite, saw her novel as the sign of “a new period in Negro fiction” – “today the young educated Negro is enlightened and angered and disgusted in depths and on heights that disdain both the past and the present.”Stanley Kauffmann, “Torn Loose” (review of The Flagellants), New Republic, 156 (24 June 1967), p. 18.

Polite was also in desperate need of the financial assistance her grant bestowed. She was working on a second novel, Sister X and the Victims of Foul Play, published in 1975. Her grant file includes 100 pages of her first draft. As Polite described it,

[T]he theme of the work is the “social reality” of the “engaged” Black American outside of the USA… I am attempting to reproduce the rhythm and tone of the English language as spoken by my People…. I am interested in “slavery or moon time” language, those expressions, whether illiterate or intellectual, which will communicate in both the moment, and “plain” English – the black psyche during this epoch of our half-liberated existence.

Carlene PoliteCarlene Polite grant application, 13 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

James Alan McPherson, “writer of insight, sympathy, and humour”

The advisory committee unanimously recommended support for James Alan McPherson, who at twenty-five was a graduate of Harvard Law School, author of an acclaimed short-story collection, Hue and Cry, and a contributing editor for the Atlantic Monthly, among other accomplishments.Ralph Ellison praised McPherson’s “insight, sympathy, and humour” in his letter to Edward Weeks, 17 February 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG. 1.3, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

McPherson applied for the grant with some ambivalence, as he believed that full funding was not good for the creative life. McPherson knew he had good prospects: “I am black, and marketable, because I have a sound academic background.” But he also feared that as a writer he would soon face pressure to “become one of many spokesmen for the masses of black people.” He explained, “My major concern is with maintaining control over my own mind, my own individuality, and my own perceptions. I do not want to be polarized.”

With the grant money, McPherson hoped to leave the country and travel to Liberia, to study “that American experiment in black colonization.” He needed to experience more and gain “time to think.”James Alan McPherson grant application, 7 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center. McPherson never made this trip, as he worked to complete his MFA and took on various teaching obligations. The novel on which he was working gave him trouble, but his second story collection, Elbow Room, published in 1977, won him the Pulitzer Prize.

I do not want to be polarized.

James Alan McPherson

After reading an advance copy of Hue and Cry, Ralph Ellison also recommended McPherson to the RF. Ellison, a rare Black voice in the selection process, was not on the advisory committee, but was a nominator and frequently served as a kind of talent scout for the Rockefeller Foundation program. A National Book Award winner (1953) and author of Invisible Man, Ellison explained that McPherson’s stories left him

…feeling more hopeful concerning the possibility of American literature becoming enriched through the special contributions of young writers who combine the Ivy League experience with the rich and complex general experience of Negro America. Now, at last, we appear to have a writer who knows how to … make one illuminate the other.

Ralph EllisonRalph Ellison to Edward Weeks, 17 February 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG. 1.3, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Ellison and McPherson, each in his own way, appreciated elite educational institutions and shared a belief in the importance of transcending what Saul Bellow once called a “minority tone.”Hilton Als, “In the Territory: A Look at the Life of Ralph Ellison,” The New Yorker, 7 May 2007.

Ellison became a mentor to McPherson and a good friend. While they shared a similar concern over maintaining an independent and authentic voice, Ellison strangely coupled his praise for McPherson with a harsh condemnation of “those talented but misguided writers of Negro American cultural background who take being black as a privilege for being obscenely second-rate…. McPherson’s stories are in themselves a hue and cry against the dead, publicity-sustained writing which has come increasingly to stand for what is called ‘black writing.’”Ralph Ellison to Edward Weeks, 17 February 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG. 1.3, Series 200R Rockefeller Archive Center.

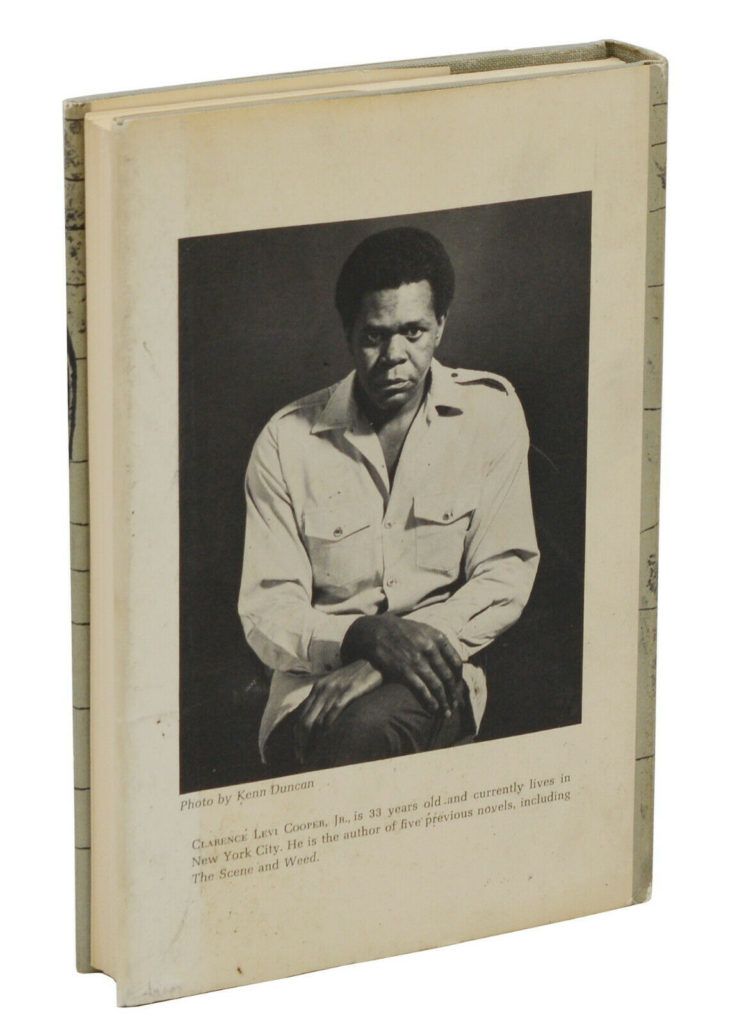

Clarence L. Cooper, Jr., “burns to write”

Clarence L. Cooper, Jr., age 35, seemed an unlikely choice for an Imaginative Writing program grant.The “burns to write” characterization is from John Ciardi’s letter to Gerald Freund, 1 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center. Committee member Mark Smith was not being ironic in noting that “the wisdom of the committee at times baffles me: I was certain I would come to the last meeting the lone voice praising Clarence Cooper.”Excerpt, Mark Smith to Gerald Freund, 20 April 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.Instead, the committee had unanimously approved his selection.

A crime novelist, Cooper wrote about what he knew. As John Ciardi explained it,

His subject matter is the ghetto, drugs, the drug Hospitals, the rehabilitation centers… he knows this twilight world intimately. At the core of everything, he is writing about masked identities. I think he is doing so in a way that could be important to American writing…. Cooper … writes the way a leopard pounces, and I am always grateful for the grace with which he carries his violence.

John CiardiJohn Ciardi to Gerald Freund, 1 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Ciardi believed that Cooper “has earned the right to a great deal of faith.”John Ciardi to Gerald Freund, 1 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.Cooper had published six novels between 1958 and 1967, some of them written from prison, where, as a heroin addict, he was serving time on drug charges. William Melvin Kelley nominated Cooper as “the single best qualified writer I know.” He hoped that a Rockefeller grant would allow him to slow down as he wrote.William Melvin Kelley to Gerald Freund, 25 March 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.Cooper’s “personal manager” had also approached the RF about a possible grant. In his application, Cooper outlined his plan for an epic novel tracing the physical, social, and moral evolution of a Black man and his family from 1861 to the present.

The essential question of the work is whether a human revolution for brotherhood has succeeded.

Clarence CooperClarence Cooper grant summary, 17 September 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In the months following his grant award, Cooper reportedly completed the first draft of a new book.William Bradley to Herbert Gluck, 16 February 1970, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.While every reviewer agreed that Cooper was an extraordinary writer with even more promise, that promise extinguished when he died destitute in New York in 1978. As Cooper summed himself up in 1963, “Clarence Cooper, Jr. is black and cannot get along with the world.”From Cooper’s introduction to his compilation Black, cited in Tony O’Neill, “Down and Out in New York,” The Guardian, 13 September 2007, Books blog, accessed 21 August 2020.

Ernest J. Gaines, Louisiana Storyteller

Ernest J. Gaines was twice nominated (in 1964 and 1966), for an Imaginative Writing program grant before finally being selected in 1969. The RF grant summary, which combined praise with unselfconscious racism, noted that Gaines was “one of very few black writers who received recognition before black writers were in fashion.” Ernest J. Gaines grant summary, 8 July 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.Gaines had had a fellowship to Wallace Stegner’s prestigious Creative Writing Workshop at Stanford in 1958-1959, and he’d authored two novels and a short story collection. Gaines wished to use his RF grant funding for travel and research in the Louisiana Bayou Country. His project – to tell the story of a woman born in slavery who lives until the 1960s – resulted in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, which he published in 1971, to great acclaim. Alice Walker called it “a grand, robust, most valuable novel that is impossible to dismiss or to put down.”Neil Genzlinger, “Ernest J. Gaines, Author of ‘The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman,’ Is Dead at 86.” New York Times, 5 November 2019.

Walter Van Tilburg Clark, novelist of the American West and cowboy culture, praised Gaines for what he saw as his palatable style.

[Gaines has a] controlled ability to present the bitter plight of the Southern Negro without becoming, himself, a bitter polemicist. His people are real people, not mere symbols of a cause.

Walter Van Tilburg ClarkWalter Van Tilburg Clark to Gerald Freund, 10 February 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Gaines himself later described his need to write as stemming from his disappointment in the “great works” of the Western canon. He wrote, he said, because these novels “were not describing my people, my aunt, my brothers or my friends whom I played ball and marbles with. I did not see me.”Neil Genzlinger, “Ernest J. Gaines, Author of ‘The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman,’ Is Dead at 86.” New York Times, 5 November 2019.

Michael Thelwell, a writer “embroiled … in the life of his time”

Writer and activist Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, twenty-nine when he received his grant, was best known for his critical essay on William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner. In his letter of nomination, Robert Coles described Thelwell as a “sensitive” and “lyrical” writer, whose essays are written “as a novelist would, rather than as a polemicist.”

The distinction is increasingly important these days. I’m referring here not to literary style so much as a cast of mind, a capacity for ambiguity – and also a willingness to struggle for one’s ideas… The balance is all important.

Robert ColesRobert Coles to Gerald Freund, 27 November 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Thelwell outlined an ambitious grant project for a novel, a play, and a political essay, related in theme and intent. The novel would focus on the “question of violence in the culture and psychology of the rural black community in the [A]merican south,” drawing on the linguistics and folklore of Black and African American culture. The play, as well as the political essay, would center on the civil rights struggle in Mississippi, which Thelwell knew firsthand from his work with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and as field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the mid-1960s. Thelwell saw the essay as intentionally polemical, as he wished to address historical and political misperceptions that in his view were “becoming dogma” for the Black liberation movement.

My intention is to attempt to restore some sense of proportion and perspective to the struggle.

Michael ThelwellThelwell to Gerald Freund, Work Plan, 7 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In support of Thelwell’s nomination, his teacher, editor, and colleague Jules Chametzky concluded simply that “he is a real man and a real writer, embroiled emotionally and intellectually in the life of his time…. More than most, Thelwell has the chance and the ability to go the route; anything we can do to help will bring grace to all our lives.”Chametzky to Gerald Freund, 16 May 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

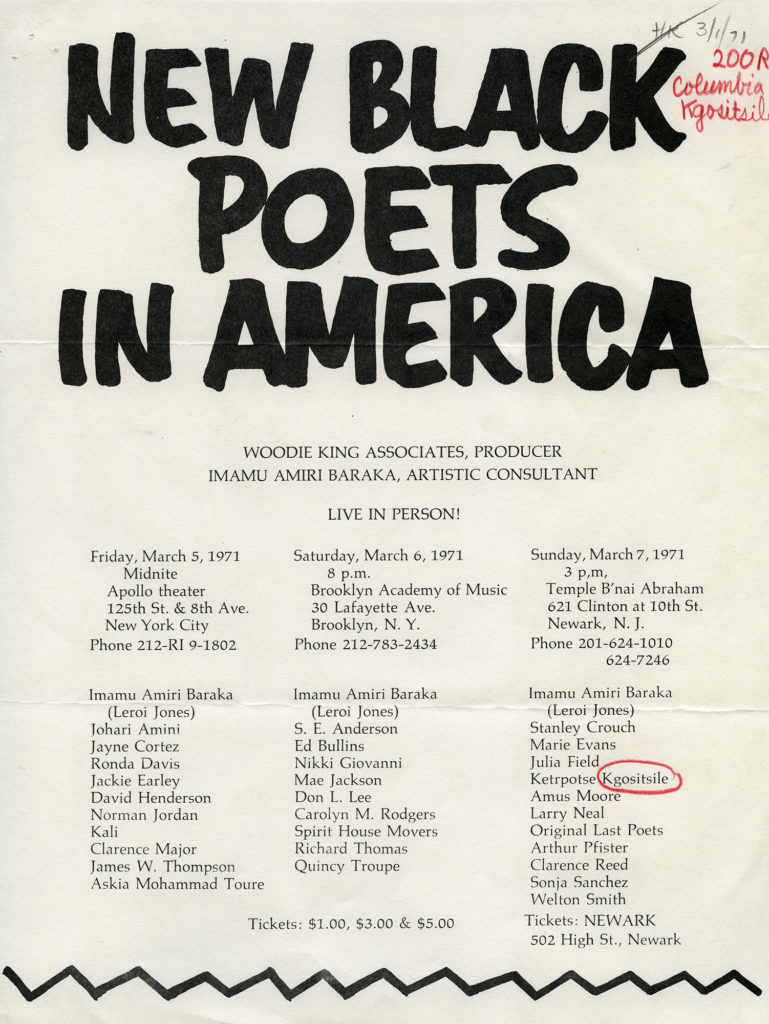

Keorapetse William Kgositsile, an African “link”

Keorapetse William Kgositsile was a poet and essayist who came to the US in exile from South Africa in 1962. Nominated by Ronald Milner in 1968 and 1969, he garnered endorsements from LeRoi Jones and Gwendolyn Brooks, among others. Woodie King, Jr. was not alone in rating Kgositsile “one of the most respected Black poets in this country.” Woodie King, Jr. memo to Gerald Freund, 3 December 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Cnter. Ronald Milner termed him “the most important young writer developing in the world today – yep, the world.”Milner to Gerald Freund, 3 February 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.King explained how Kgositsile’s arrival in the US coincided with a rising interest among Black Americans in a “neo-African thing.” Kgositsile could speak about Africa, and American Blacks could in turn tell him “how we felt about Africa.” Milner echoed this opinion:

He [Kgositsile] seems and “sounds” like the embodiment and verbalization of the African “link” needed for total integration and understanding of Black-Identity – he goes for no Chauvinistic levels of Brotherhood nor does he have that inane sense of superiority over the ex-slaves. His sense of brotherhood is total and international.

Ronald MilnerMilner to Gerald Freund, circa 5 February 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Not everyone could relate to this “African link.” Asked by the advisory commitee to weigh in on Kgositsile’s talents and potential, Elizabeth Kray, chair of the Academy of American Poets, called his poems “long, rambling, and vaguely expressed.” Bluntly invoking that clichéd double standard, she opined that “If he were white, he wouldn’t merit a grant.”Elizabeth Kray to Gerald Freund, 29 January 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Still, Kray conceded that Kgositsile had been “a positive, moderating force” in his work with the Academy’s public-school program and that he “makes a fine example for the young Black groups.” An RF grant might be an investment that would “help shape a genuine literary outlook in the young Black people.” As for Kgositsile himself, she concluded, dismissively, “Probably he will become a good essayist.” A grant to him would “be of educational – not artistic – benefit.”Elizabeth Kray to Gerald Freund, 29 January 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The committee seems to have paid little mind to Kray’s biased and patronizing opinions, and went ahead and awarded him a fellowship. The RF grant summary in his file describes Kgositsile’s poetry as “rough-hewn anger reflective of the conditions of Blacks in the United States and South Africa alike.” With his grant funding, Kgositsile proposed to enroll in the writing program at Columbia University and to work on a book-length experimental poem.

While in New York, he also helped found the Black Arts Theatre in Harlem, which was part of a larger project aimed at the creation of a literary Black voice unafraid to be militant. Kgositsile returned to Africa in 1975, first to Tanzania, and then to South Africa in 1990, where he became Advisor to the Minister of Arts and Culture.

Black Writers and the Imaginative Writing Program in the Late 1960s

What unites this cohort of Black writers in the late 1960s, and why were so many of them selected in the writing program’s final year? Many of them wrote of Black identity, searching, as did William Melvin Kelley, to parse their relationship to Africa and their place in the world, or to tell the stories of lives lived or worlds known. Several of the grantees proposed traveling south to Mississippi or east to Africa on their grants to gain a closer knowledge of the culture from which they came. Language was a central concern to all these writers. They wrote as their characters spoke – in the syntax and rhythm of the Black vernacular, of the bayou, of the moon-time language, or of the streets. Violence is another theme, either the violence done to African Americans through the long legacy of slavery and racism, or violence within relationships or the broader culture. All were unquestionably imaginative writers, capturing their culture, reaching for the mythical or the heroic (or anti-heroic), engaging with the world around them.

There is also an undercurrent that runs through many of these grant files: a judgment, not always positive, on how “Black and aware” a writer was. From MacLeish’s yearning for a “writing that knows no color or differences,” to Ralph Ellison’s strange diatribe against second-rate Black writers, there is a concern about polarization and polemicized writing. The Imaginative Writing program spanned the years from 1964 to 1969, which also saw the signing of the Civil Rights Act, the rise of the Black Power Movement, the assassination of Malcolm X in 1964 and of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, urban unrest, etc. By 1969, the mention of Black solidarity and anger is commonplace in the notes of evaluators and grantees alike.

Woodie King, Jr. Diversifies the Decision-Makers

There is no evidence that the Rockefeller Foundation believed it gave any overt weight to racial diversity in its nomination or selection process (though we may not have full records of the advisory committee deliberations). However, it seems clear that race was on the table.

Something changed the final year, when a full third of the grantees were Black. To be sure, the times were changing, and maybe the Rockefeller Foundation was catching up. More particularly, the advisory committee had added the influential Black theater director and producer Woodie King, Jr. to its membership. A theater consultant for the RF and a trusted advisor, King appears to have been an outspoken voice on the advisory committee on behalf of many or most of the Black candidates.

The Imaginative Writing program did not continue long enough for the 1969 cohort to become, in turn, advocates for other Black writers’ nominations, so it is impossible to know whether Black representation among the grantees might have continued to expand.

The Right Way?

Some of the fellows are now considered “Lost Giants,” as their works have been rediscovered and reissued. Others are, or were, respected teachers, writers, and critics. They include among them a MacArthur Fellow (McPherson) and a Poet Laureate of South Africa (Kgositsile). All were exceptional candidates of great promise.

Looking at their collective stature, it seems hard to believe that they underwent such scrutiny for their respective identification (or lack thereof) with Blackness and Black culture. In supporting them, the Rockefeller Foundation did bring broader meaning to the Imaginative Writing program and may have taken a further step toward its goal of helping “the right writers, at the right time, in the right way.” However, the archives reveal that it was also a struggle to get the right people recognized for the right reasons.

Research this Topic in the Archives

- “Program and Policy – Creative Writing,” 1964-1972, 1975, Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, RG3, SG 3.1 and 3.2, Subgroup 2, Humanities, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Creative Writing – Evaluations of Nominees by Advisory Committee,” 1965-1966, 1968-1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, RG3, SG 3.1 and 3.2, Subgroup 2, Humanities, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Bellow, Saul – (RF Humanities Consultant),” 1950-1951, 1964, 1966, 1982, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Milner, Ronald Scott,” 1965-1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, Fellowships, RG 10, Fellowship Files, SG 10.1, United States, Series 200, Fellowships, Scholarships, Training Awards, Subseries 200.E, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Columbia University – Pharr, Robert D. – (Creative Writing, Fiction),” 1966-1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Freund, Gerald (rockarch.org),” Rockefeller Foundation records, Biographical File, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Kelley, William Melvin – (Creative Writing, Fiction),” 1968-1970, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Sarah Lawrence College – Jordan, June – (Poet),” 1967-1972, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Sarah Lawrence College – Jordan, June Meyer – “Who Look at Me”,” 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Rutgers University – Polite, Carlene – (Creative Writing),” 1968-1969, 1971, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Yale University – Ellison, Ralph – (Creative Writing, Fiction),” 1964-1966, 1971, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Hofstra University – Cooper, Clarence – (Creative Writing, Fiction),” 1968-1971, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Stanford University – Gaines, Ernest – (Creative Writing, Fiction),” 1969-1971, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of Massachusetts – Thelwell, Michael – (Creative Writing, Fiction),” 1968-1971, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Columbia University – Kgositsile, K. W. – (Creative Writing, Poetry),” 1968-1969, 1971-1972, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, (Grants), RG1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “King, Woodie Jr.,” 1940s-1960s, Rockefeller Foundation records, Secretary’s Office, RG 15, Biographical Files, Staff, A-Z, Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.