Ireland’s newfound independence in the 1920s fired imaginations. After centuries of crushing British colonization, reclaiming Irish identity became the nation’s aspiration and unflinching aim. It seems extraordinary, in retrospect, that an independent Ireland could ever be perceived as “too Irish.” However, at the time, with the adoption of Irish nationalistic ideology and public policies for the resuscitation of the Irish language, a “non-English speaking” Ireland proved too much for some.

It even affected the seemingly apolitical field of medical education.

The Rockefeller Foundation and Global Health Funding

For more than a century, the Rockefeller Foundation has had a working hand in global health initiatives. It has often focused its efforts on improving medical outcomes for populations at risk or in need. Historically, one way of advancing this goal has been to provide funding for the reorganization and modernization of medical education around the world.

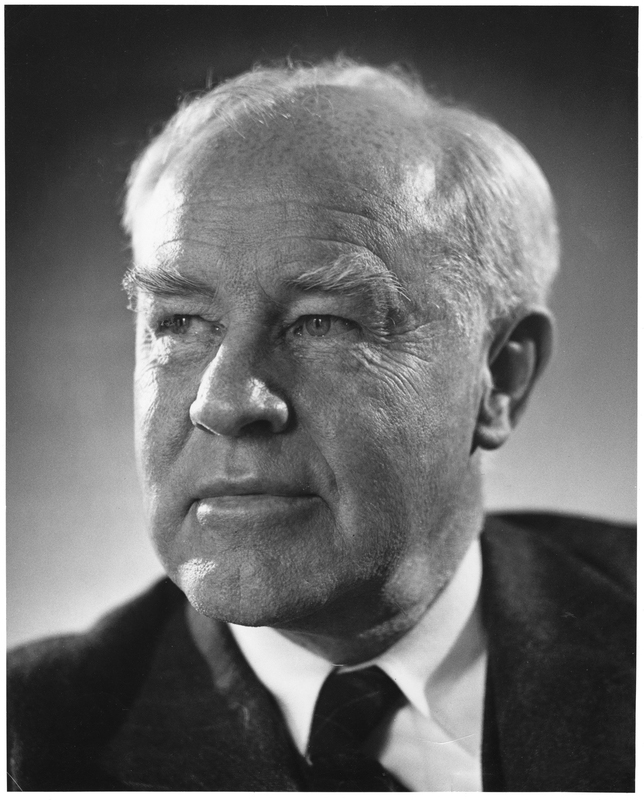

In the 1920s, the Foundation’s Division of Medical Education (later known as the Division of Medical Sciences) was headed by Alan Gregg, a Harvard-educated physician with a British Medical Corps background. Gregg went on regular fact-finding pilgrimages throughout Europe to inspect medical schools and universities with the objective of recommending how Rockefeller aid could help.

In the case of Ireland, Gregg’s resistance to the cultural shifts brought about by the Irish Free State’s sovereignty from Britain proved to be an obstacle to enacting the Foundation’s usual approaches.

Surveying the Field of International Medicine

It was Gregg’s task to investigate and report on the political and social stability of the countries he visited, as well as to assess the ability, integrity, and good intentions of those under consideration for funding. Gregg delivered this information to the Foundation in a thorough Survey Report of his visits.Alan Gregg, ‘A survey of medical education in Ireland,’ May 1925. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1.1, Ireland, Series 403, Ireland – Medical Sciences, Subseries 403.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

However, Gregg’s daily activity logs (known in the Foundation as an Officer’s Diary) record additional whereabouts, conversations, and experiences. As such, his diary provides contemporary readers with a unique and detailed glimpse into the various regions Gregg visited and their people, culture, and perspectives at the time. It also evidences Gregg’s own attitudes, perhaps shedding light on why the Rockefeller Foundation ultimately abandoned its plans to reform Irish medical education.

There is no unanimity of political opinion in Ireland as far as we have seen it: indeed, the only agreement is the agreement that there is no agreement.

Alan Gregg, 1925

National Identity in Independent Ireland

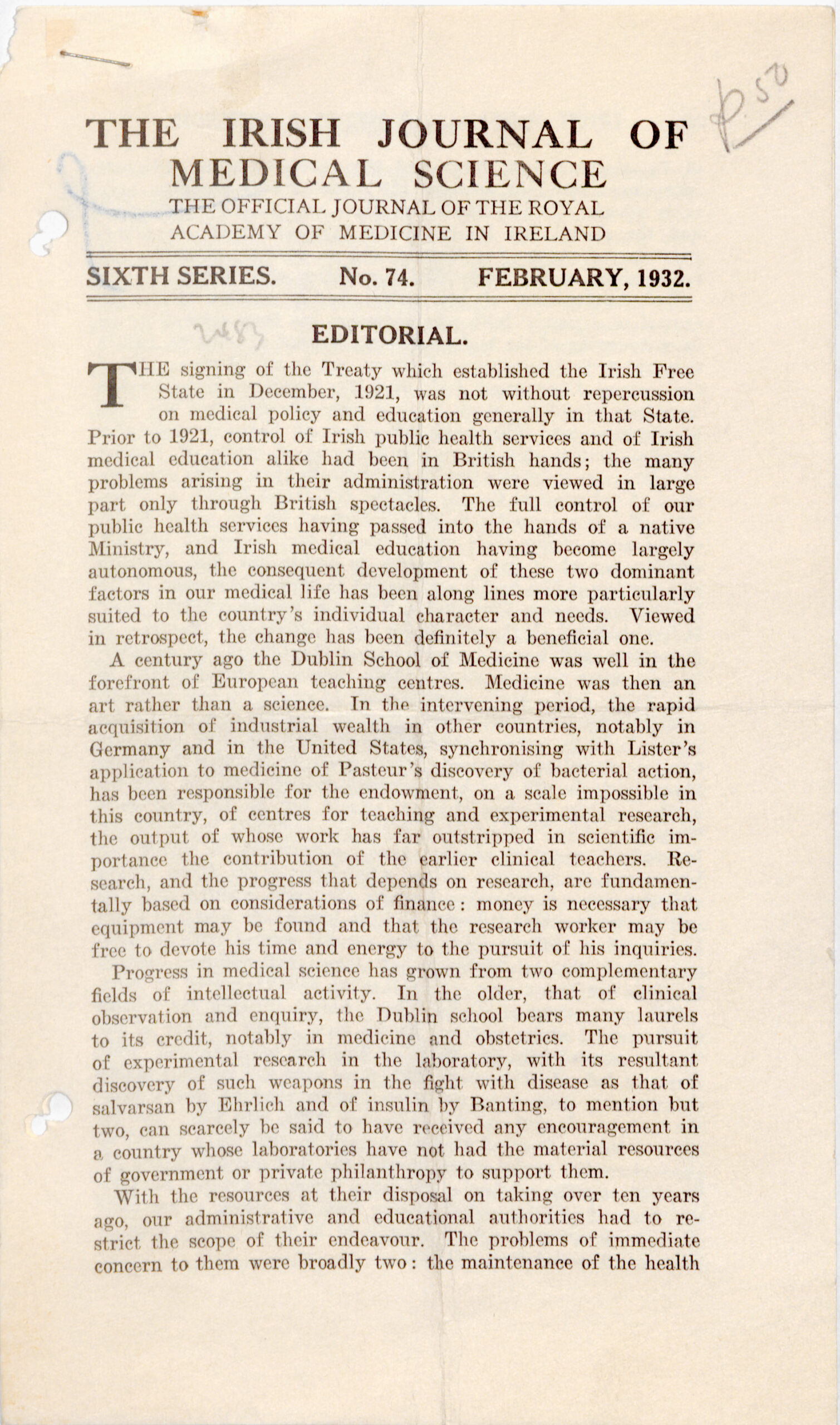

Visiting Ireland in 1925, Gregg encountered a country undergoing rapid reform and reconstruction. Having recently won its independence from Britain’s repressive rule, Saorstát Éireann (the Irish Free State) was established in December 1922. This included the creation and partition of Northern Ireland, six counties in the north to remain under British governance. A devastating civil war resulted. As Gregg understood, the severing of relations with the rest of the British Isle had also brought about a crisis in the funding of medical research and training.

But by mid-decade, Ireland’s new governing forces were less concerned with modifications in medical education than with ushering in major cultural changes. They introduced a broad focus on Irish nationalism with an emphasis on Irish identity and a rejection of British culture. This ideology also gave rise to revitalization efforts for the languishing Irish language, recognized by Irish speakers as “Irish,” or more broadly known as Gaeilge. As a language, Irish was considered unique to the country and, therefore, of crucial importance to Irish cultural expression and to world heritage. Over generations, however, for some it had also come to be synonymous with poverty, inferiority, and backwardness.

A Long History of Irish Language Suppression

In 1922, the new Free State government made the Irish language an essential part of the curriculum for all National Schools after a dark history of exclusion and English-only instruction.

Ireland’s national primary education system had been established in 1831 and included a ban on teaching Irish. This policy continued until the end of the 1870s. Corporal punishment was often used on children if they spoke in Irish at school. Teachers were penalized if they taught through the medium of Irish. The Irish education system at the time encouraged students to choose English over Irish if they wanted to be prepared for working life in Ireland or abroad.

When compulsory Irish became necessary for national civil service appointments in 1926, a commission extended these regulations also to local government. This had considerable impact upon the medical profession, as the regulations covered many in the field: dispensary doctors, tuberculosis officers, medical officers of health, veterinary officers, and the medical staffs of publicly run hospitals, sanatoriums, and asylums.

When describing to the Foundation the “significance” of Ireland’s new presiding government, Gregg’s views were not positive. “Broadly speaking Ireland is being governed by the representatives of a part of the population which up till now has never been politically or intellectually in ascendancy,” he wrote. “It is a group representing but little in tradition, education, intelligence or administrative experience.”Alan Gregg, ‘A survey of medical education in Ireland,’ May 1925, p.10. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1.1, Ireland Series 403, Ireland – Medical Sciences, Subseries 403.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.Gregg called the situation “not dissimilar to that obtained in the American colonies at the time of our revolution [from Britain].”Alan Gregg, ‘A survey of medical education in Ireland,’ May 1925, p.10. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1.1, Ireland Series 403, Ireland – Medical Sciences, Subseries 403.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

A Funder’s Resistance To the Irish Language Movement

Ironically, despite noting this similarity, Gregg’s writings reveal his distinct disapproval for Irish nationalists and their insistence upon qualifications in the Irish language for graduation in Ireland’s system of higher education. As Gregg reported to the Foundation in his Final Survey:

There has been an active nationalist movement to revive the Irish language. The government has been strong in its support of this movement. The pressure has come largely from the intellectuals and extreme nationalist patriots, but practical men of affairs, and in some cases the peasants themselves, discredit the enforced adoption of Gaelic in the elementary schools simply because it involves so great a waste of time and effort on the part of the pupils.

Alan Gregg, 1925Alan Gregg, ‘A survey of medical education in Ireland,’ May 1925, p.6. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects(Grants), Record Group 1.1, Ireland, Series 403, Ireland – Medical Sciences, Subseries 403.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Gregg seemed to feel that the revival of the Irish language was at best trivial and, at worst, prejudicial. He cast anti-nationalists as “practical” (a trait held in high regard among Rockefeller Foundation program officers) as well as under threat of discrimination by nationalists, whom he viewed as extremists.

Practical men seem almost unanimous in their opinion that the attempted revival of the Irish language is not justified, but that if no great opposition is raised this movement will die of itself. The National University in its three branches [comprising the University Colleges of Galway, Cork, and Dublin] includes Irish among their requirements for matriculation; the effect of these requirements is to exclude the students coming from families who do not sympathize with the extreme expression of nationalism.

Alan Gregg, 1925Alan Gregg, ‘A survey of medical education in Ireland,’ May 1925, p.6. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1.1, Ireland Series 403, Ireland – Medical Sciences, Subseries 403.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Roots of Resistance

The full extent of the reasons for Alan Gregg’s opposition to the country’s Irish nationalist movement are not entirely known. Some of Gregg’s contemporaries considered the new course of governance a threat to the status quo. Certainly, the Rockefeller Foundation had more than a decade of close working relationships already established in England (not to mention that Gregg himself had served in the British Medical Corps). Others feared that too much authority would be doled out to the Catholic Church, which was more sympathetic to the Irish language cause.

“Home Rule will be Rome Rule” was a disparaging phrase echoing among Loyalists around the country.

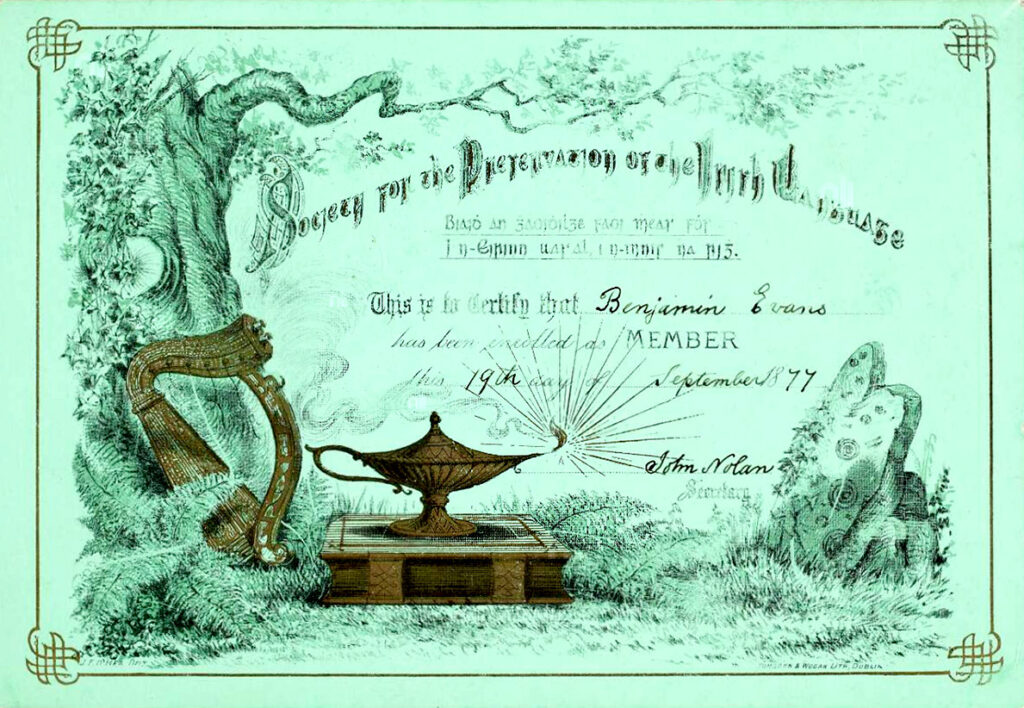

Gregg erroneously reported back to the Foundation that only “since 1916” had the Irish language revival been in play. Indeed the 1916 Easter Rising against Britain influenced this new wave of Irish nationalism. However, Gregg failed to realize that there had been an emerging Gaelic revival since the end of the 19th century. Apolitical organizations such as the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language, the Gaelic League, and the Gaelic Athletic Association were at the forefront of the renaissance of Irish language and culture half a century before the formation of Saorstát Éireann.

Debate and Disapproval for Irish Nationalism

Alan Gregg’s diary provides added insight into the origins of his disapproval for Irish nationalism. His itinerary included four days in Dublin, one day in Cork, two days in Galway, and a final day back in Dublin. At every location, non-medical conversation often veered into talk of the new Free State government, Republicanism, recent troubles, or the Irish language. As such, Gregg’s diary paints a focused (if often predisposed) account of the attitudes found in the Irish counties he visited in the mid-1920s. It also expresses Gregg’s greater comfort level in areas where nationalist fervor was not wholeheartedly embraced.

On Friday, May 15, 1925, after attending a dinner with influential politicians on Fitzwilliam Square in Dublin, Gregg recorded highlights from the evening’s conversations, capturing the turmoil that Irish independence had fostered:

Struck by the anxiety the [new Free State] government feels to keep in touch with American Irish. Senator Douglas [the Vice Chairman of the Senate and head of White Cross] said the greatest danger to the use of and spread of the Irish language was the intolerance of the American-Irish. Also impressed by the fact that Irish history is being exploited to the utmost as a means of solidifying Nationalistic feeling – but the trouble is nobody knows much… Barniville [a surgeon at the Mater] was the articulate realist of the party and said it was more important to reduce taxes and get on sound footing than to waste time over the Irish language and old history. An interesting group of men.

Alan Gregg, 1925Alan Gregg, 1925, p.50. Rockefeller Foundation records, Officers’ Diaries, Record Group 12, F-L, 1925, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Later that same week, on Monday, May 18, 1925, he describes a calmer situation in Cork that he seems to tie to milder nationalistic sentiments:

Apparently a year or two ago very few people believed the Free State would survive at all: now many people are thinking it will and that things have calmed down amazingly in the last year… Cork, a school small but well housed…it differs from University College Dublin (its mate) in being…less intensely Nationalistic in feelings of its personnel and consequently more in touch with England.

Alan Gregg, 1925Alan Gregg, 1925, p.52. Rockefeller Foundation records, Officers’ Diaries, Record Group 12, F-L, 1925, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Linking Language and Nationalism to Poverty

However, in Galway the following day, Tuesday, May 19, 1925, Gregg describes a quite different environment. Here, he equates poverty and social unrest with more pervasive nationalist sentiments. (Note: the Black and Tans were an extra police force sent from England to Ireland in 1920 to contain the Irish Republican Army.)

This is the part of the country that Irish is still the colloquial tongue and students come here to learn the language…There is no unanimity of political opinion in Ireland as far as we have seen it: indeed, the only agreement is the agreement that there is no agreement. Absentee ownership, the natural difficulty of existence, and the memories of the Black and Tans seem to be the source of bitterness and bleakness of life – but ignorance, a large birthrate, and a horrible climate seem involved in any picture I can make of the region, and a clergy overtopping the population in a crushing manner and in other matters of the Spirit too.

Alan Gregg, 1925Alan Gregg, 1925, p.52. Rockefeller Foundation records, Officers’ Diaries, Record Group 12, F-L, 1925, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Yet despite Galway’s observable poverty and broad use of Irish, Gregg admitted that the county had “the best hospital I have seen yet in Ireland…The only place where a pathological lab is attached to the hospital.” Davitt, the full-time professor of clinical medicine, mentioned to Gregg that his father was an ardent Irish patriot but forewarned: “If Ireland ever secured autonomy, it would be a good place to stay out of for the first ten years.” Gregg understood this to mean “that the training of the people who had never had any experience in government would cost the country a great price.”Alan Gregg, 1925, p.52. Rockefeller Foundation records, Officers’ Diaries, Record Group 12, F-L, 1925, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Unsatisfactory Conditions for Medicine in Ireland

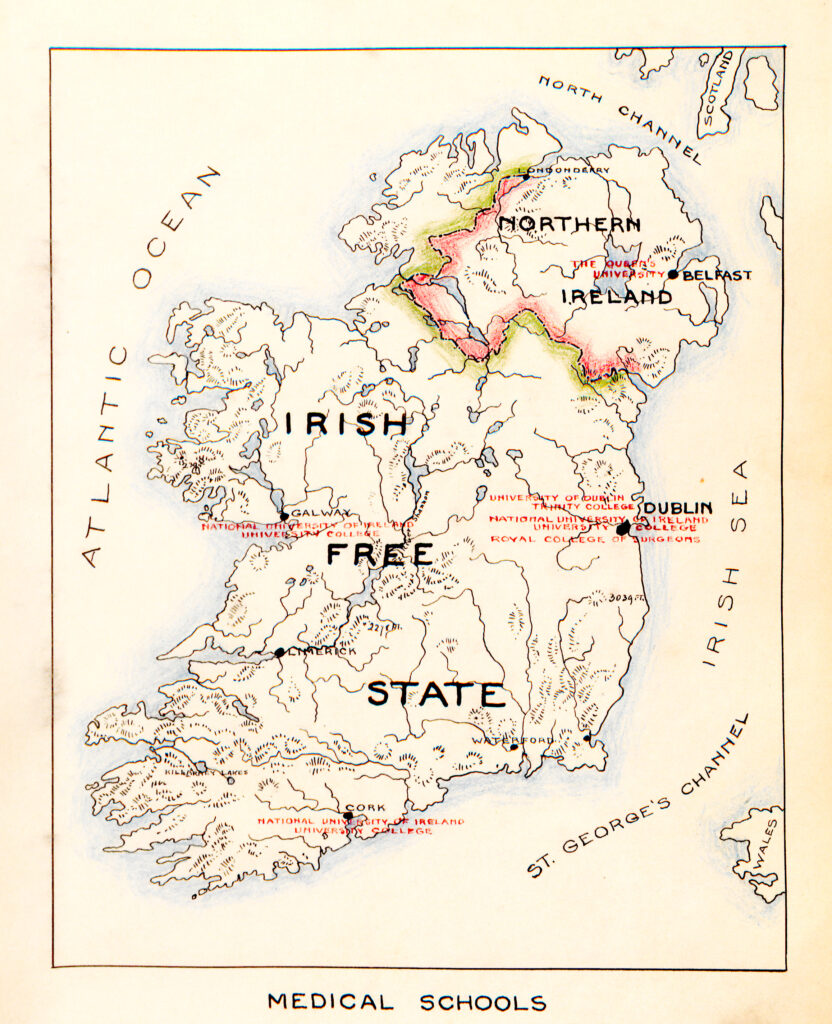

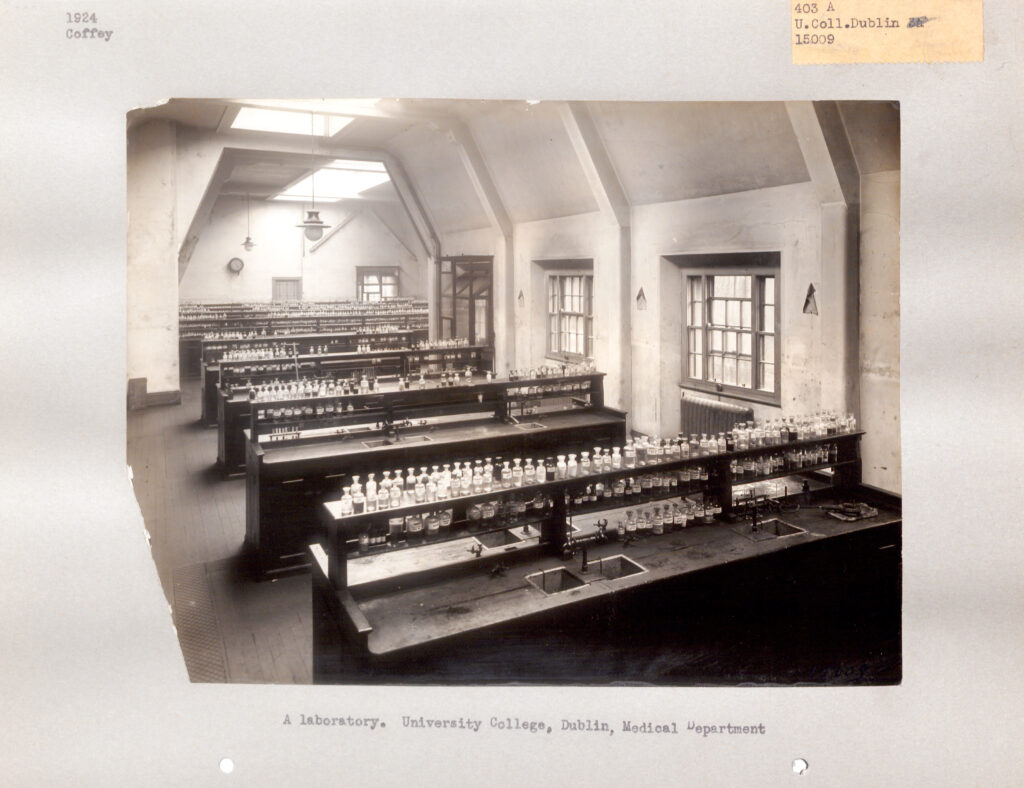

In the end, Alan Gregg ultimately viewed the state of the medical profession in the new Saorstát Éireann as unsatisfactory. “Irish medical schools take little account of the necessities of developing teachers, and even less of the desirability of training research men,” he wrote.Alan Gregg, ‘A survey of medical education in Ireland,’ May 1925, p.261. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1.1, Ireland Series 403, Ireland – Medical Sciences, Subseries 403.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The problem was compounded, he believed, by poor teaching of the sciences in Irish secondary-level schools. Moreover, it was Gregg’s opinion that the Free State, with a population at that time of just over 3 million, was in fact over-supplied with medical schools. There were six. In the period 1921-25, the average annual number of medical graduates per year produced by all the schools in the Free State was 305. Gregg felt that 50 graduates per year was the most that Ireland could realistically absorb. However, persuading medical schools to reduce their intake would prove unpopular since these schools depended upon student fees for survival.

A Dearth of Doctors in Ireland

At the same time, despite the abundance of medical school graduates, Gregg was critical of the uneven distribution of medical professionals in Ireland. For example, the lack of pediatric care particularly dismayed him:

…visit to the Coombe (76 beds for Gynecology and Obstetrics) …Disappointed at everything at the Coombe. Surprised to find that newborn are obliged night and day to be in the same bed with mother; ‘Only two babies overlain intentionally in the last few years’ said the matron. One mother with twins in narrow bed did not look happy. [Sir William Taylor, Physician at the Adelaide] says there is no field for a pediatrician in Dublin and that there is none.

Alan Gregg, 1925Alan Gregg, 1925, p.54. Rockefeller Foundation records, Officers’ Diaries, Record Group 12, F-L, 1925, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In some ways, Ireland’s situation seemed ideal for the kind of reforms the Rockefeller Foundation regularly enacted around the world. Indeed, the Foundation had established its reputation through strengthening medical institutions and improving health services for populations in need, particularly for the poor and for children. Yet a key component of the design of the Foundation’s programs was co-operation with local governments. Foundation staff were always cautious about working in unstable situations, especially political instability.

Confronting the Separate Medical Registration Requirement

Just such instability interrupted Gregg’s reporting in the summer of 1925 with the emergence of the issue of medical registration. The active registry was originally open to all doctors practicing anywhere within the British Isles. But now the Free State government put forth a proposal to set up a separate register for Ireland.

National Library of Ireland

The debate about an Irish medical registration elicited heated opinions on the impact of larger cultural and intellectual attitudes in medicine. The Irish Times, then a staunch unionist newspaper, was blunt in its 1925 reporting about Gaeltacht regions — districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home:

The impoverished Gaeltacht is the temple of their hopes, and the tyranny of the Irish language is the symbol of their policy. There is no doubt that these narrow idealists have imposed their will on the Free State Government in the matter of the British register.

Irish Times editorial, August 22, 1925Quoted in The Leader, August 29, 1925, p.78.

Eventually, the Medical Practitioners Act of 1927 settled the registration issue. This legislation established a separate register for Irish doctors and gave the regulation of qualifications to the medical register in Ireland.

The Rockefeller Foundation Abandons Its Plans for Ireland

The medical registration crisis seemed to be the last straw for the Rockefeller Foundation. Added to the series of challenging conditions Alan Gregg had observed, this latest turmoil prompted Foundation staff to abandon plans for the reorganization of Irish medical education.

Nevertheless, Gregg made a return trip to Ireland in 1927 because he and Rockefeller Foundation colleagues sought co-operation between the two major institutions of medical education in Dublin: Trinity College and University College (UCD). Rockefeller Foundation staff members still hoped there could be one excellent medical school in the Irish Free State.

But the Foundation’s relationship with UCD soon soured — in Gregg’s opinion, due to the institution’s embrace of emphatic nationalism. For its part, Trinity considered itself under siege because of the language question. Rockefeller Foundation leaders began to see that the medical register crisis was but one issue among many facing Irish medicine, and the issue of language remained far from resolved. At this point, the Foundation retreated from the situation entirely.

In the end, the Rockefeller Foundation continued to offer a small number of project grants to individual medical institutions and personnel throughout the 1930s. Its plans for sweeping, structural medical education reform in Ireland were not to be, however.

A Century of Uncertainty for Ireland and the Irish Language

As for the developing Free State that Alan Gregg had visited in 1925, it continued its persistent path forward — as did the Irish language.

The year 2022 marked one hundred years since Saorsát Éireann came into being and constitutionally declared Irish as both its national and an official language. On January 1, 2022, the Irish language finally gained full status as an official language of the European Union, giving Irish equal status with the other twenty-three official languages of the EU. Also in 2022, Irish became an official language in Northern Ireland for the first time. Finally, as if to prove the mainstream appeal of the tenacious tongue, the 2022 film An Cailín Ciúin/The Quiet Girl became the first Irish-language film to be nominated for an Academy Award in the best international feature film category.

It had been a century of struggle, but as Irish revolutionary Michael Collins had prophesied so hopefully in 1922:

Irish will scarcely be our language in this generation, nor even perhaps in the next. But until we have it again on our tongues and in our minds, [Ireland is] not free.

Michael Collins, The Path to Freedom, 1922.

Further Reading

- Andrew Hull, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Attempts to Seed Scientific Medicine in Europe, Britain and the Empire after 1919: The Welsh National School of Medicine, Cardiff.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2009.

Related

Early 20th Century Reforms of Medical Education Worldwide

Working to change US medical education was one of the Rockefeller Foundation’s biggest endeavors in the 1910s and 1920s, extending from Johns Hopkins in Baltimore to Beijing, China.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s 20th-Century Global Fight Against Disease

Programs designed to build public health infrastructure, eradicate disease, and increase access to healthcare have formed the core of more than a hundred years of one foundation’s strategy.

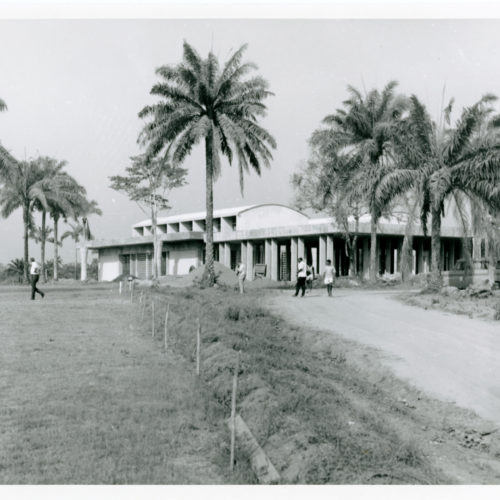

The Rockefeller and Ford Foundations Navigate Civil War in Nigeria

What happened to a massive agricultural development program when war broke out?

Philanthropy’s Fight Against Tuberculosis in World War I France

What does it take to control the outbreak of a deadly disease?