The 1974 World Population Conference in Bucharest marked the contentious beginning of what would prove to be a long transition in the reproductive health agendas of philanthropic foundations and global agencies.

In the early 1970’s, fears about the dangers of overpopulation reached a fever-pitch. The popularity of Paul R. Ehrlich’s bestseller The Population Bomb, released in 1968, introduced the general public to the idea that population control was urgently needed to avoid the catastrophic effects of an ever-increasing birth rate.

Demographers and other population experts in the West had long held these fears. They had made it their mission to reduce the birth rate in “developing” countries through the distribution of contraception and sterilization programs.

In this climate, population experts went to the the 1974 World Population Conference in Bucharest, Romania optimistically. With the waning of conservative attitudes about contraception and a shared acceptance of the dangers of overpopulation — at least in the US and Western Europe — they expected to secure support for zero-population-growth initiatives.

Instead, to their surprise, they met forceful resistance from participants from newly independent nations and feminists from across the globe. In short order, stemming in large part from the events of the Bucharest meeting, the global agenda on population would be fundamentally reconfigured.

The new approach to population control would de-center male-dominated Western authority and would call for the sovereignty of women over their own bodies. Furthermore, it would place family planning in the realm of broader, grassroots-directed development work shaped by countries themselves. In the wake of the Bucharest meeting, new, female leadership would emerge in the population field while longtime male leaders grumbled or even stepped aside.

Resistance to Population Control from Women and the Global South

The institutionalization of a woman-centered approach to family planning at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, long credited with institutionalizing woman-centered approaches to population, actually had its seeds in the conversations leading up to and following the 1974 Bucharest conference.

While in some ways a success story for feminist reproductive health advocacy, this transition was not necessarily a smooth one. Documents from the Rockefeller Foundation records, the Population Council records, the John D. Rockefeller 3rd papers, and the Ford Foundation records in the years surrounding the 1974 conference reveal a contested and gendered moment of transition. As the global feminist movement gained influence and citizens of recently decolonized nations voiced critiques of Western imperialism, the establishment population “experts” defensively guarded the legitimacy of population growth as an issue as well as their own status as experts.

The 1974 World Population Conference in Bucharest

The 1974 World Population Conference was the third International Conference on population organized by the United Nations. It came at critical juncture in the field population studies. Population experts from US-based foundations expected the Bucharest conference to result in commitments to zero population growth, especially in nations experiencing what they considered to be dangerously high birth rates.

By the end of the two-week conference, these expectations had been roundly corrected. While neo-Malthusianism had reached a zenith, so too had the women’s movement and decolonization. It was, by all accounts, a contentious gathering. Matthew Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population, Vienna Lecture Series (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), 313.

On one side of the conflict was the population establishment, composed largely of demographic and medical experts, officers of organizations and foundations, and delegates from the US and other countries in the West. Among them were program officers from the Ford Foundation and the Population Council (the latter having received funding from the Rockefeller Foundation). At Bucharest, these officers, all of whom were men, hoped to establish consensus on the dangers of rapid population growth and then to institute a broad intergovernmental agenda to slow population growth in the Global South.

Activists and delegates from newly independent nations, as well as feminists from across the globe, made up the opposing faction. This faction contested very idea that birth rates in the “developing” world should be reduced.Oscar Harkavy, Curbing Population Growth: An Insider’s Perspective on the Population Movement, 1st ed. 1995., The Springer Series on Demographic Methods and Population Analysis (New York, NY: Springer US, 1995), 66.

The 1974 World Population Plan of Action

The World Population Plan of Action, a proposed document that had been created over many months with Sweden and the US taking the leading role, laid out specific commitments to control fertility. However, this draft was repeatedly rejected throughout the conference, with more than 300 amendments eventually added.

Coalitions began to form among nations in the Global South. Many conference participants, including even some employees of the United Nations Fund for Population Activities, openly contested the Malthusian framework that undergirded the population establishment’s views. Issues of national sovereignty, women’s empowerment, and human rights emerged to take center stage.Matthew Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population, Vienna Lecture Series (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), 313.

Delegates from nations that were new members of the UN advocated for their own sovereignty in these matters. They were suspicious that donor governments, such as the US, and their allied agencies would meddle in their internal affairs.

In this context, the commitment to zero population growth was dead on arrival. The US proposal recommending a reduction in the average size of families was out-and-out rejected by a majority of delegates. The version of the World Population Plan of Action that was ultimately adopted deemphasized the importance of controlling birth rates. The final plan instead stated that countries should commit:

[to] ensure that family planning, medical and related social services aim not only at the prevention of unwanted pregnancies but also at the elimination of involuntary sterility and sub fecundity in order that all couples may be permitted to achieve their desired number of children, and that child adoption may be facilitated.

“World Population Plan of Action” (United Nations Population Information Network, 1974)

In the words of Oscar Harkavy, director of Ford’s population program from 1963 to 1980, “the expected worldwide consensus on the need to reduce birthrates through family planning failed to materialize.”David C. Korten, “Organizing and Managing the Population Program in the Post-Bucharest Era: Harvard University.” 1975. Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Reports 010112, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Overpopulation or Reproductive Autonomy?

At the core of these debates was not only the “how” and “who” of the issue, but also the “why.”

For one, there was the question of who should run population programs. For years male experts from the West, often demographers or medical doctors, conceived and ran programs that distributed contraception, funded sterilization, and engaged in other reproductive health measures. Feminists from across the globe expressed deep dissatisfaction with this system.

Delegates from the Global South sounded alarms about reproductive abuse and the eugenic implications of population control programs administered by the West. Feminists argued that local women and local experts were in the best position to run these programs and respond to community needs.

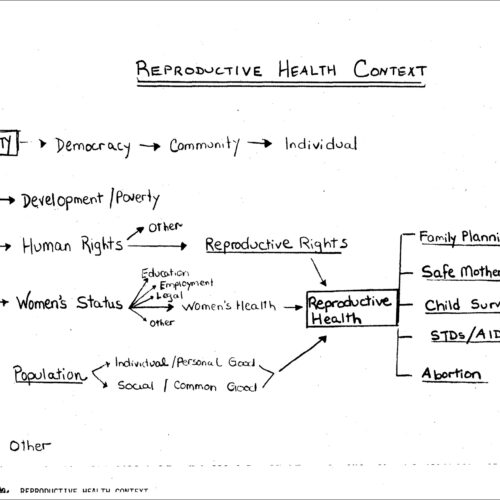

Also at stake in these conversations was the validity of targeting population size as a problem and then proposing population control as a solution to a range of social ills. Did we need contraception to stave off a looming disaster of overpopulation? Did we need to achieve zero population growth? Or should the goal of family planning instead be to allow women and their partners agency over how many children they had, understanding family size as interrelated with other development goals?

“Development is the best contraceptive”

Many delegates from “developing” countries pushed for understanding poverty in the context of global economic conditions and the production unequal development in the Global South rather than pressures of population size.

Sheldon Segal, head of the medical sciences division at the Population Council from 1963 to 1978, summarized this sentiment with a much-publicized quote from Karan Singh, an Indian politician present at the conference: “development is the best contraceptive.” In this vein, the following year, Harvard academic David C. Korten characterized the prevailing takeaway in a background paper solicited by the Ford Foundation in 1975:

[D]evelopment ultimately concerns the progress of people rather than the progress of factories and that both economic growth and fertility decline are means, not ends.

David C. Korten, 1975David C. Korten, “Organizing and Managing the Population Program in the Post-Bucharest Era: Harvard University.” 1975. Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Reports 010112, Rockefeller Archive Center.

This perspective, while not completely at odds with the views of the population establishment, posed a challenge from many within it by questioning their reliance on population control methods as the vector to solving larger issues. Ultimately, the final World Population Plan of Action put forth a view of the “population problem” as just one part of larger questions of development and quality of life.

The Role of Women in Population Control

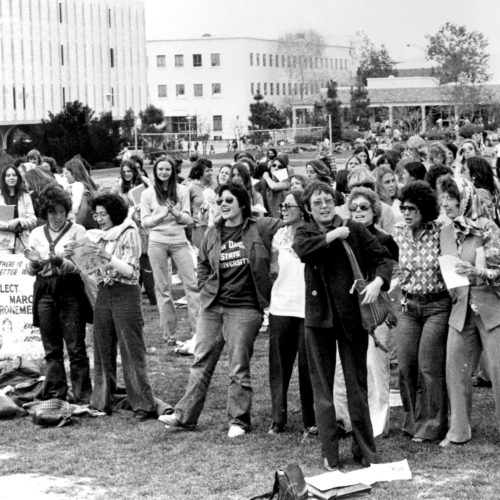

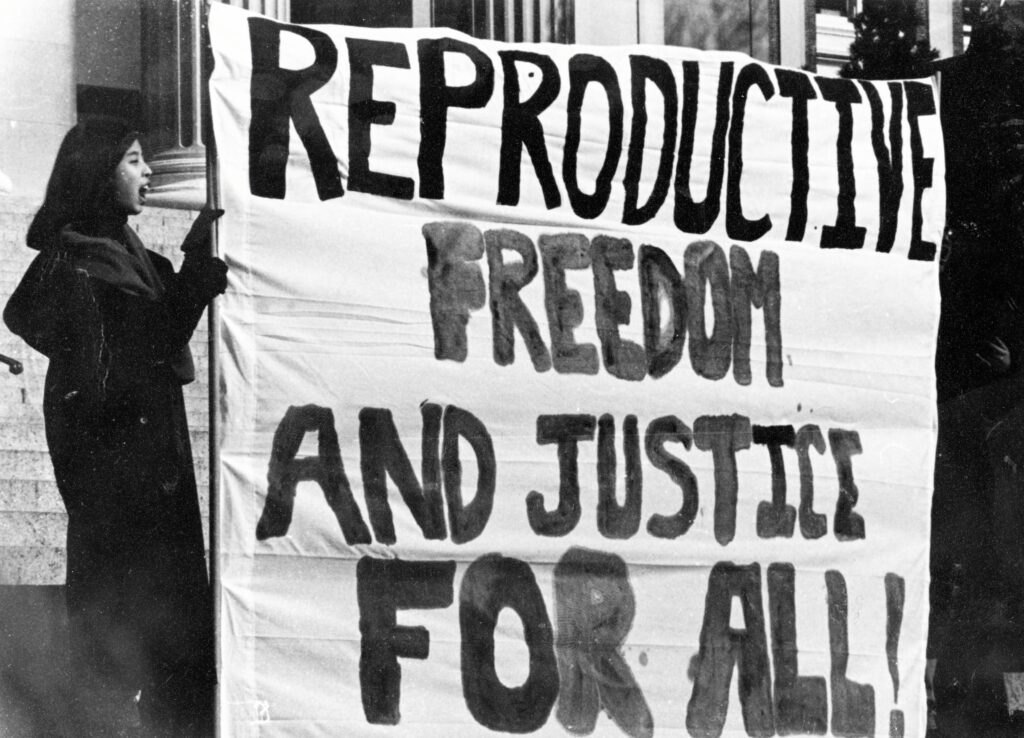

The other central tension that emerged at the conference was the role of women in discussions about population control. In Bucharest, feminists from US and Europe, including Margaret Mead, Germaine Greer, and Betty Friedan, joined women from the Global South at Bucharest to amplify their concerns.

While there was a diversity of perspectives on issues of family planning, many women called for centering women’s reproductive autonomy in concrete terms. They rejected the sterile, statistical language used by demographers and protested the lack of attention to women in drafts of the World Population Plan of Action. As Greer stated,

[I]t failed to recognize that if women were offered no alternative role to child‐bearing, they would never be motivated to contribute to society in any other way.

Germaine Greer, 1974Nan Robertson, “Barley Gives Bucharest a Taste of Overpopulation,” New York Times, August 24, 1974.

Many argued that issues of reproduction were fundamentally connected to larger questions of justice and gender equity. They asserted that broader development goals like women’s education and employment would contribute to the reduction of birth rates.

Demographically-informed population control programs and reproductive health initiatives led by local and indigenous women’s groups may both have focused on contraception. However, the motivations behind these programs, their goals, and intellectual and ethical frameworks were critically different.Jason L. Finkle and Barbara B. Crane, “The Politics of Bucharest: Population, Development, and the New International Economic Order,” Population and Development Review 1, no. 1 (1975): 87–114. In these analyses, population as a problem was framed as an issue of woman’s rights, something violated, for example, both by coercive sterilization programs and through pro-natalist, anti-abortion programs.

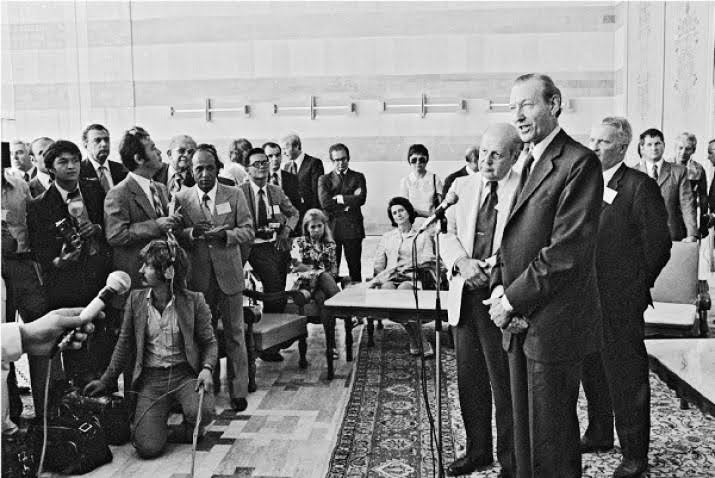

These tensions came to a head during perhaps the most shocking moment to those in attendance: John D. Rockefeller 3rd’s speech.Rebecca Sharpless interviews with Joan Dunlop, April 14–15, 2004, Population and Reproductive Rights Oral History Project, SSC. Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population, 313.

An Influential Population Funder Reverses Course

John D. Rockefeller 3rd had long been a leader in the movement to reduce population. He was the founder and chairman of the Population Council and early proponent of the field of population studies.

However, to a packed room in Bucharest, he seemed to reverse course. To the delight of feminists and Global South delegates, he called for a “deep and probing reappraisal” of the issue and a “new and urgent attention to the role of women.”Rockefeller, John D. “Population Growth: The Role of the Developed World.” Population and Development Review, vol. 4, no. 3, 1978, pp. 509–16.

Rockefeller’s remarks focused not on the looming economic and social catastrophes of overpopulation but on women’s bodily autonomy and the empowerment of women through development work. In other words, rather than defending the policies of the Population Council, JDR 3rd’s speech mirrored the very same concerns voiced by feminists.

…a new and urgent attention to the role of women…

John D. Rockefeller 3rd, speech delivered at the UN World Population Conference at Bucharest, 1974

A Call for the “Full Integration of Women” in Family Planning

The final version of the World Population Plan of Action reflected both Rockefeller’s speech and the demands of feminists and others. It called for a much more expansive understanding of population policy and included language referencing personal and national sovereignty. It called on all countries to “respect and ensure […] right of persons to determine, in a free, informed and responsible manner, the number and spacing of their children.”“World Population Plan of Action” (United Nations Population Information Network, 1974), 7.

The World Population Plan of Action specifically underscored the role of women, calling for “the full integration of women into the development process, particularly by means of their greater participation in educational, social, economic and political opportunities.” The previously primary goal of reducing population size of nations in the Global South was sidelined in favor of a plan that defined issues of health and family planning in broader terms, often in tandem with maternal and child health concerns.Lyle Saunders and Oscar Harkavy, “ERIC – ED142454 – Population Issues: From Obscurity to Worldwide Interest. Population: Before and after Bucharest [And] Ford Foundation Programs: Review and Projection. A Ford Foundation Reprint., 1977-May.”

…the right of persons to determine, in a free, informed and responsible manner, the number and spacing of their children…

World Population Plan of Action, August 1974

Population Experts React to the Woman-Centered Approach

Many postmortem assessments were penned debating the “population problem” post-Bucharest. They reveal that changes in the field of population, as experienced by individuals within foundations, were accompanied by gendered rivalry, conflict, and resistance.

Many foundation accounts register both a sense of surprise and a desire to adopt this emergent agenda. Evaluations such as Korten’s, which characterizes Bucharest as “a major step toward a more sophisticated approach to population issues,” abound in the archival records.David C. Korten, “Organizing and Managing the Population Program in the Post-Bucharest Era: Harvard University.” 1975. Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Reports 010112, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Ford’s Oscar Harkavy identified Bucharest an “important factor in disturbing the donor community’s generally held assumption that high rates of population growth negatively affected socioeconomic development.”Harkavy, Curbing Population Growth An Insider’s Perspective on the Population Movement, p.66.

Sheldon Segal noted that, despite the frustrations of the architects of its original World Population Plan of Action, the final plan had seeds of what would soon become the norm: the integration of family planning into woman-centered, maternal health programs and the idea that questions of overpopulation should be incorporated into broader development goals.

Roots of a Less Technocratic Approach to Population

Many of these post-mortem evaluations also reveal that the changes emerging from Bucharest reflected ideas that had been percolating for some time. In 1967, demographer Kingsley Davis published an article that became influential in population circles.Kingsley Davis, “Population Policy: Will Current Programs Succeed?” Science, New Series, Vol. 158, No. 3802 (November 10, 1967), pp730-739. It argued for a broader, more socially minded, less medicalized and technocratic approach to family planning. In other words, the notion that “population policy consists of more than a family planning services delivery program” had been circulating for some years.David C. Korten, “Organizing and Managing the Population Program in the Post-Bucharest Era: Harvard University.” 1975. Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Reports 010112, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Population policy consists of more than a family planning services delivery program.

David C. Korten, 1975

This idea was embraced by Ford Foundation program officer Lyle Saunders. In a paper delivered at the annual meeting of Ford’s international division in September 1975, Saunders called the Bucharest developments a question of timing. According to Saunders, these events “occurred at a time when change was in the wind, and it was becoming obvious that new definitions, new strategies, and new tactics were going to be required.”Saunders and Harkavy, “ERIC – ED142454 – Population Issues: From Obscurity to Worldwide Interest. Population: Before and after Bucharest [And] Ford Foundation Programs: Review and Projection, 1977, p.6. Kingsley Davis, “Population Policy: Will Current Programs Succeed?,” Science 158, no. 3802, 1967, pp.730–39. He also characterized these changes as a shift away from questions of demography and toward politics and a pivot from focus on economic progress to focus on social progress. For many, at least retrospectively, Bucharest and its combative exchanges marked a shift in frameworks and policy that foundations, and their predominantly male staff, would eventually need to lead.

Feminist Influence or “Backlash?”

However, these foundation reports tend to ignore the influence of feminism on policy change. For example, while Ford had spent massively on the development and distribution of contraception throughout the middle of the twentieth century, those efforts had stemmed from an intention “to limit population growth, not an effort to meet women’s needs.” Susan M Hartmann, “Financing Feminism: The Ford Foundation” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 137.

It wasn’t until feminism gained a louder voice at Ford that the conceptual framework of these programs began to shift. Ultimately, Ford’s rank-and-file women workers brought a feminist consciousness to the Ford Foundation.

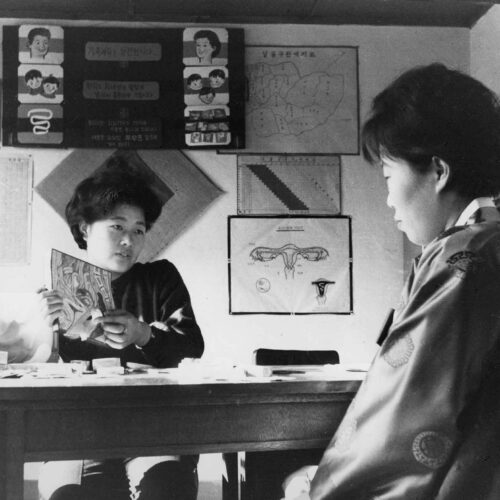

A Gender-Conscious Shift in the Development Paradigm

The shift in development paradigms following Bucharest was also part of larger shifts that made more room for the involvement of women. The 1960s saw foundations transition from technocratic, broad-brush approaches, rooted in a belief that scientific methods could address the root causes of social ills, to so called “micro-development” programs — smaller programs with an emphasis on grass-roots activities, based on a community development model.Daniel Immerwahr, Thinking Small : The United States and the Lure of Community Development (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015); Kathleen D. McCarthy, “From Government to Grass-Roots Reform: The Ford Foundation’s Population Programmes in South Asia, 1959-1981,” Voluntas (Manchester, England) 6, no. 3 (1995): 292–316.

In the case of population programs, this shift was a contested process. In this period, knowledge and expertise about family planning, contraception, and reproduction were fundamentally reconceptualized to focus on women, and foundation grantees diversified.

Feminist philosophers and historians of medicine have long argued that technocratic and often medicalized approaches of the kind employed by male demographers and population experts align with a certain form of gendered, masculinized knowledge production. In this case, contraception and reproduction, traditionally feminine areas, came under the dominion of male expertise in part through the mobilization of scientific discourses of overpopulation and demography.For more on the gendering of knowledge see: Susan Bordo, “The Cartesian Masculinization of Thought,” Signs 11, no. 3 (1986): 439–56; Sandra Harding, “Is Gender a Variable in Conceptions of Rationality? A Survey of Issues,” Dialectica 36, no. 2–3 (1982): 225–42; and for masculinization and medicalization of childbirth see Judith Walzer Leavitt, Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750 to 1950 (Oxford University Press, 2016).

This gendered struggle over the issue of population is evident in the private communication leading up to and following Bucharest. Many in the “old guard” felt uneasy about de-centering population growth and wary about feminism. This apprehension is reflected in their interactions with John D. Rockefeller’s aide and advisor, women’s health advocate Joan Dunlop.

Last Gasp of the Male Population Establishment: The Bellagio Population Conference in 1973

The radical nature of the shift at Bucharest can be understood in comparison to another major global meeting, held only one year earlier. The discussions at a May 1973 meeting held at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Conference Center shed light on the gendered conflict soon to emerge. They paint a picture of a male population establishment that was quite sure of itself ahead of Bucharest.

A year before Bucharest, two dozen experts gathered at the luxurious Villa Serbelloni overlooking Lake Como in Bellagio, Italy. There was not one woman among them and only two participants hailed from the Global South. Nearly all of the attendees had a background in demography or medicine.

These men gathered at this lavish spot to discuss foreign assistance to national family planning programs. (Notably, by 1978, Vice President of Ford’s International Division David E. Bell would deem this and other luxurious locations inappropriate for such a meeting.) Some Bellagio attendees expressed excitement that a global consensus about population was imminent with the upcoming UN conference in Bucharest.Harkavy memo, April 22, 1975, and Bell handwritten notes, ca. June 1977, “Possible Bellagio IV Population Meeting; 1975-1976,” Ford Foundation records, Administration, Office of the Vice President, Office Files of David Bell, Population Files, Series V, Meetings and Conferences, Subseries B, Rockefeller Archive Center. Cited in Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population, p.313.

Bell moderated the conference and presented a summary of events on the final day. He indicated that ideas that would come to the fore at Bucharest regarding the integration of population programs into larger health program were indeed percolating. Bell wrote,

[T]here is impressive testimony that individuals see family planning in a context of family problems…child health, nutrition, family health, housing and so on. This raises the question of whether family planning programs can be effective by themselves, or whether we should move into a period in which family planning will be integrated into action programs for comprehensive family health, or maternal and child health and nutrition”

David Bell, May 1974John D. Rockefeller 3rd (John Davison) (1906-1978), Lelewar, David K., Dunlop, Joan (1934-2012) and David Bell, “‘The Population Conference’ Bellagio III, John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Associates, David K. Lelewar and Joan Dunlop,” Series 2 (Joan Dunlop Files) Box 2, no. Folder 22 (May 1974): 2.

Bernard Berelson, president of the Population Council, suggested this might be a watershed moment and encouraged foundations to integrate family planning into larger structures. Bell, however, made note of the critiques mounted by attendees from “less-developed countries” that foreign assistance for population programs in the developing world was “too simple, too coercive, too narrow.”John D. Rockefeller 3rd (John Davison) (1906-1978), Lelewar, David K., Dunlop, Joan (1934-2012) and David Bell, “‘The Population Conference’ Bellagio III, John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Associates, David K. Lelewar and Joan Dunlop,” Series 2 (Joan Dunlop Files) (May 1974), p.3.

However, Berelson did not mention the role of women.

The Bellagio discussion remained fixed on the goal of zero population growth, despite the tentative introduction of more holistic approaches.

Critiques Emerge from the Global South

However, the summary of the Bellagio conference that Berelson prepared for John D. Rockefeller 3rd candidly notes that “a certain ‘backlash’ seems to be emerging.”John D. Rockefeller 3rd (John Davison) (1906-1978), Lelewar, David K., Dunlop, Joan (1934-2012) and Bernard Berelson, “Population Conference, Bellagio III,” John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Associates, David K. Lelewar and Joan Dunlop,” Series 2 (Joan Dunlop Files) (1974), p.12.

Citing international events like the Accra Conference in 1971, Berelson listed criticisms ranging from the “‘overselling’ of population as a panacea for social ills, overstress on family planning as against [maternal and child health] and public health […] the spurious effort ‘to buy development cheaply,’ the escape of the rich countries both politically and economically.”John D. Rockefeller 3rd (John Davison) (1906-1978), Lelewar, David K., Dunlop, Joan (1934-2012) and Bernard Berelson, “Population Conference, Bellagio III,” John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Associates, David K. Lelewar and Joan Dunlop,” Series 2 (Joan Dunlop Files) (1974), p.12.

Berelson seemed equally dismissive of and concerned by these trends. Given the resonance of these critiques mounted at Bellagio with those that would come to dominate at Bucharest, Berelson was likely unsurprised by much of what would unfold in 1974.

…a certain ‘backlash’ seems to be emerging…

Bernard Berelson, 1973

Joan Dunlop: Rise of a New Influencer

If unsurprised by the criticisms coming from developing nations in general, Berelson was nevertheless quite surprised and even hurt by John D. Rockefeller 3rd’s Bucharest speech. Rather than defending zero population growth and the population establishment, JDR 3rd echoed the sentiments of the so-called “backlash,” as Berelson identified it. This apparent realignment shocked feminists and those from the developing world as much as it did population insiders.

Berelson’s reaction was particularly strong. He had drafted an early version of the speech Rockefeller would deliver at Bucharest. But his version was not the speech Rockefeller ultimately made.

The ideas that structured Rockefeller’s speech instead were developed through his interactions with his aide Joan Dunlop. It was Dunlop, a health advocate and activist hired in 1973 to bring a fresh perspective to the issue of population, who engaged Rockefeller more deeply with feminism. Looking at the population establishment and the all-male events, including the 1973 Bellagio conference, Dunlop recalled in an interview that she put the issue quite candidly to Rockefeller during this time:

A very small number of men control all the money and the ideas in this field. They have a stranglehold on it and there is really no innovation.

Joan DunlopRebecca Sharpless interviews with Joan Dunlop, April 14–15, 2004, Population and Reproductive Rights Oral History Project, SSC. Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population, 313.

Dunlop’s comments on early drafts of Berelson’s version of John D. Rockefeller 3rd’s Bucharest speech presciently reflected the very concerns that would come to dominate the conference. In her line-by-line assessment of the Berelson draft, she wrote,

Little mention of: population is not an isolated issue; the dearth of knowledge expressed at Bellagio, family health and family planning; income distribution, economic motivation. […] thin sense of Third World in-put. It does not deal with the humanity and politics of ideological differences and power…

John D. Rockefeller 3rdJohn D. Rockefeller 3rd (John Davison) (1906-1978), Asia Society, Population Council, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Population Interests, Subseries 5 , p.2

Joan Dunlop Critiques the “Sexless” Approach to Population

As Peter Johnson explains in his biography of John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Joan Dunlop wanted this speech to “put population activities within the context of the overall development process” while Berelson wanted to focus exclusively on reducing birth rates. Dunlop thought this approach “sexless” and stated that for these men “it was all very theoretical.”

[The early draft] does not deal with the humanity and the politics of ideological differences and power…

Joan Dunlop, 1974John D. Rockefeller 3rd (John Davison) (1906-1978), Asia Society, Population Council, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Population Interests, Subseries 5 , p.2

Ultimately, Rockefeller agreed with Dunlop’s insights. It was Dunlop, along with women’s health advocate Adrienne Germain, who wrote the final draft of the speech he ended up delivering. With this speech, Dunlop’s influence over JDR 3rd became clear, as did Rockefeller’s alignment with feminist views and therefore, his rejection of Berelson’s priorities.John Harr and Peter Johnson, The Rockefeller Conscience (Scribner, 1991), 429. Rebecca Sharpless interviews with Joan Dunlop, April 14–15, 2004, Population and Reproductive Rights Oral History Project, SSC.

Other longtime leaders in the foundation-supported population movement, including Oscar Harkavy, Frank Notestein, and Sheldon Segal, were dismayed by the speech. Sheldon Segal, Under the Banyan Tree: A Population Scientist’s Odyssey. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); Harkavy, Curbing Population Growth An Insider’s Perspective on the Population Movement; Harr and Johnson, The Rockefeller Conscience. Berelson and Notestein were particularly upset, given their close relationships with Rockefeller. Even Segal, who had developed a model for women’s clinics in India in the 1960s, felt “glum.” He had the feeling that JDR 3rd had “sold them out” at Bucharest.John Harr and Peter Johnson, The Rockefeller Conscience, 30.

Berelson’s Bitter Resignation Makes Way for a Gender-Conscious Approach to Population

Berelson stepped down as president of the Population Council due to ill health almost immediately following the Bucharest conference. Given the timing, it seems likely that the rift between JDR 3rd and Berelson also played a role.

In his resignation letter, Berelson wrote at length about the dangers of the Population Council losing sight of “population.” Correspondence between JDR 3rd and Joan Dunlop note Berelson’s bitter tone and the animosity simmering over Rockefeller’s embrace of a feminist approach. Peter Johnson recalls the tension between Dunlop and Berelson, describing Dunlop’s role as “more than an aide.” Dunlop had her own agenda, which Berelson saw as “deviant and threatening.”John Harr and Peter Johnson, The Rockefeller Conscience, 425.

The fallout is reflected in Joan Dunlop’s notes on a meeting between JDR 3rd and Population Council leadership, which included Parker Mauldin, Paul Demeny, Clifford Pease, and Sheldon Segal, on September 27th, 1974.

Mauldin claimed that the Population Council, contrary to the implications of JDR 3rd’s speech, had always considered family planning integral to population concerns.

Rockefeller explained his speech expressing “the increasing hostility between the developed and developing world, the urgent need for an acknowledgment on the part of the Establishment of the viewpoints from the Third World.” He was “meticulous” in reiterating his support for the Population Council to such a degree that she worried he could have been interpreted as “backpedaling” from his Bucharest speech.John D. Rockefeller 3rd (John Davison) (1906-1978), Asia Society, Population Council, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Population Interests, Subseries 5 , p.2

The interpersonal conflict among JDR 3rd, Berelson, and Dunlop reflects a broader resistance to feminist approaches during this period. To the small circle of (mostly) men who worked in what Segal called a Ford-Rockefeller-Population Council axis, Dunlop, through her influence on JDR 3rd, represented a threat.Oscar Harkavy, Curbing Population Growth: An Insider’s Perspective on the Population Movement. Springer US, 1995.

A Fresh Start at the Population Council

Joan Dunlop consulted major players from across the field in the Population Council’s presidential search to find Berelson’s successor. Yet many expressed reticence about a change of direction for the Population Council.

In a July 1975 letter to John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Dunlop notes Berelson’s resistance to new approaches to population, and by “new” she seems to indicate feminist approaches. She states that Berelson was pushing for someone from the “old guard” to replace him.

A personal letter from Berelson to JDR 3rd, which Dunlop called “sad,” “unfair,” and “unnecessary,” acknowledges this conflict. In response to JDR 3rd’s stepping down from the chairmanship of the Population Council, Berelson remarked on the changing state of affairs in the field. He wrote, “But now things have changed – in your view for the better, in my view for the worse.”Joan Dunlop and John D. Rockefeller 3rd, “‘Population Council, Agricultural Development Council,’ John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Associates, Joan Dunlop,” Abortion, Subseries 5.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

When John D. Rockefeller 3rd and Joan Dunlop eventually chose George Zeidenstein to lead the Population Council in 1976, it was against the advice of Berelson, Oscar Harkavy and others. Zeidenstein was a self-described feminist and had been a Ford Foundation field representative in Bangladesh since 1971. In Bangladesh, he had invested in local women leaders and embraced the type of holistic approach that Dunlop and JDR 3rd were after.

But now things have changed – in your view for the better, in my view for the worse.

Bernard Berelson to Joan Dunlop, 1975

Population Elites Oppose New Generation Leaders

Many within the Population Council and the Rockefeller Foundation disapproved of choosing this young, Ford field representative. Harkavy thought Zeidenstein “too junior” and was seemingly a bit offended by the suggestion of his appointment. He pushed back strongly and advocated for Sheldon Segal.

Other insiders like George Harrar, the recently retired Rockefeller Foundation President, also objected to Zeidenstein. Interestingly, Harrar’s comments reflected apparent openness to finding a female successor to Berelson. But on the other hand, they evidenced a dismissive, if jocular, tone. For example, Harrar somewhat glibly remarked that women like Bengali feminist, political scientist, and population consultant Rounaq Jahan show that “Gals can do it.”Joan Dunlop and John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Agricultural Development Council, Population Council, “‘Letter to JDR’ John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Associates, Joan Dunlop,” Series 5 (Population), Subseries 5.3, Population Council, Presidential Search and Reorganization, (July 31, 1975): 2.

Women as “Subjects, Not Objects”

In the end, despite the push-back from these figures, JDR 3rd endorsed Dunlop’s push for someone to shake things up. As Dunlop put it in a letter to Zeidenstein, they wanted someone “younger, vigorous, very much an intellectual, open to some of the contradictions and paradoxes swirling around the definition of the word population.”Joan Dunlop and John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Agricultural Development Council, Population Council, “‘Letter to JDR’ John D. Rockefeller 3rd Papers, Associates, Joan Dunlop,” Series 5 (Population), Subseries 5.3, Population Council, Presidential Search and Reorganization, (July 31, 1975): 2.

Dunlop and JDR 3rd believed Zeidenstein shared their vision, expressed in Rockefeller’s Bucharest speech, for involving women in the Global South as “subjects, not objects” of population policy.

Funders (Finally) Embrace a New Paradigm

Ultimately, most funders began to embrace a new focus on women and heeded the calls of feminists to move family planning into a broader maternal and child health agendas.Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population, 301.; Saunders and Harkavy, “ERIC – ED142454 – Population Issues: From Obscurity to Worldwide Interest. Population: Before and after Bucharest [And] Ford Foundation Programs: Review and Projection. A Ford Foundation Reprint., 1977-May.”

![Close-up of a letter closing from the Ford Foundation collections reads "Sincerely yours, [signed] Adrienne, Adrienne Germain, Program Officer](https://s30471.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/AdrienneGermainSignature.jpeg)

The Ford Foundation continued to lead the way. Ford’s program in Bangladesh, from which Dunlop had recruited Zeidenstein, was well underway by the 1974 UN conference. After the conference, Ford continued to invest more heavily in women as leaders in programs. For a program once solidly oriented toward technocratic population control goals and run by male demographers, by the end of the 1970s, Ford’s population program in Bangladesh was run by Adrienne Germain and supported grassroots, women-led NGOs, such as Concerned Women for Family Planning.Kathleen D. McCarthy, “From Government to Grass-Roots Reform: The Ford Foundation’s Population Programmes in South Asia, 1959-1981.” Voluntas, Volume 2, October 1995, pp. 292-316.

From Overpopulation to Reproductive Health

Re-gendering the field of population did occur over the next two decades. Foundations abandoned a focus on a crisis of supposed overpopulation and instead re-framed issues of reproduction and contraception as questions of reproductive health and women’s autonomy. Technocratic solutions and demographic frameworks favored by the male experts of mid-century were increasingly challenged by women across the field and in the Global South.

Although some chafed at the re-ordering of priorities and personnel, many of the men discussed here did come to embrace this change and went on to lead new programs on population that reflected feminist concerns.

The backstory of this transitional moment in the 1970s offers lessons about the gendered conflict that continues to arise in policy-making around reproduction.

It also has relevance in a moment where the birth rate has yet again emerged as a “problem”to be solved by “experts.” While in the 2020s, the concern is over birth rate decline rather than acceleration, we can learn lessons from those who pushed back against the population establishment fifty years ago.

What are the dangers of isolating the question of population from the gendered politics of reproduction? What policies and practices might be justified by accepting underpopulation as a pressing social problem? What are the alternative viewpoints?

Related

Centering Women’s Rights in the Population Field: The Ford Foundation and Sexual Health in the 1990s

A 1994 meeting moved women’s empowerment front and center for grantmaking in global population.

The Women Pioneers of Global Nursing Education Who Built the Rockefeller Foundation Program

A massive program in nursing education extended to 53 schools across the globe. But it never became a top priority of the foundation that supported it.

Rockefeller Philanthropy and Population-Related Fields

As the scarcity of global resources became increasingly worrisome in the 20th century, these organizations more boldly approached work in population and family planning.

The Fairy Godmothers of Women’s Studies

Moving scholarship by and about women from margin to center.