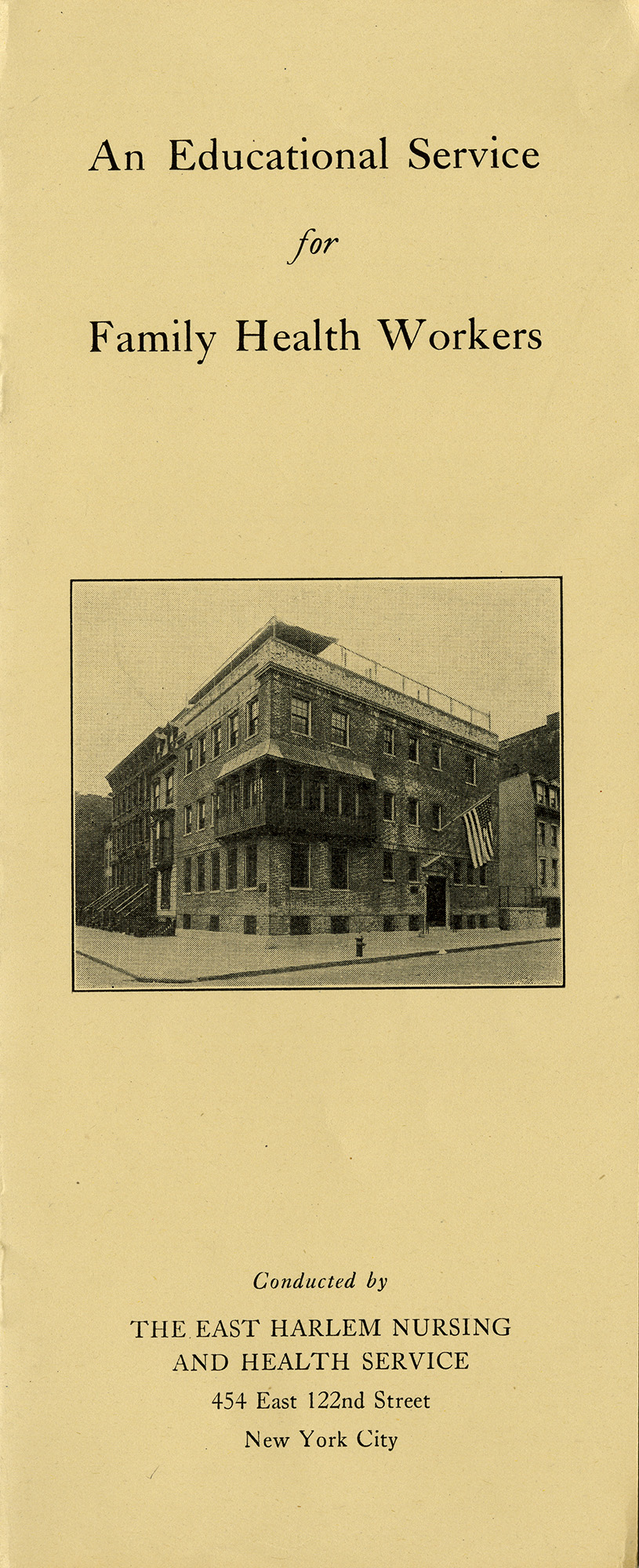

In the 1920s, a public health experiment in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood strove to be a model of effective community care — and largely succeeded. A demonstration project, the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service, was carried out at the newly established East Harlem Health Center and was innovative in several ways. The project brought together nursing training and patient care, collected and shared data and best practices, and informed public health initiatives across the United States. And yet, by 1928, the early success of its experimental phase began to descend into a longer-term institutional failure. That year, the Rockefeller Foundation (RF), which had directly and indirectly supported the project since 1922, reorganized.

While the Rockefeller Foundation wanted to terminate funding because of its own shift in programmatic strategy, it continued to support the Nursing and Health Service until 1934, in hopes that the enterprise would achieve financial self-sustainability. But soon the Great Depression hit the US, and the organization never managed to stabilize. In fact, it began to trim and alter its programs. In the transformation from experiment to institution, the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service ultimately fell short of meeting community needs. Despite the Service’s obvious struggles, in 1934 the RF declared that the East Harlem Health Center had achieved self-sustainability and terminated its grantmaking to it. The Center’s Nursing and Health Service hung on for a few more years, but folded in 1941.

Thus an early success story ultimately became a story of closure. The history of the East Harlem Health Center offers lessons in how to respond to community needs effectively, while providing a cautionary tale for grantees about remaining attentive to the shifting winds of foundation funding.

Coordinated, Efficient Healthcare

Throughout World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic that followed, American government and private organizations collaborated in an attempt to serve the military and civilians in more effective ways. These efforts often included health centers, which created more expansive and efficient services to assist the poorest of urban populations. The East Harlem Health Center, supported in part by the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (LSRM), was one such collaboration. Concerned groups created the Center to address multiple needs in a community where infant mortality was high. Additionally, its founders hoped it would become a model for similar programs throughout the country.Patricia D’Antonio, “Cultivating Constituencies: The Story of the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service, 1928-1941.” American Journal of Public Health. Volume 103 Number 2, pp.988-996. See also, Patricia D’Antonio, “Rockefeller Foundation and Health Demonstration Projects, 1920-1940,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2011.

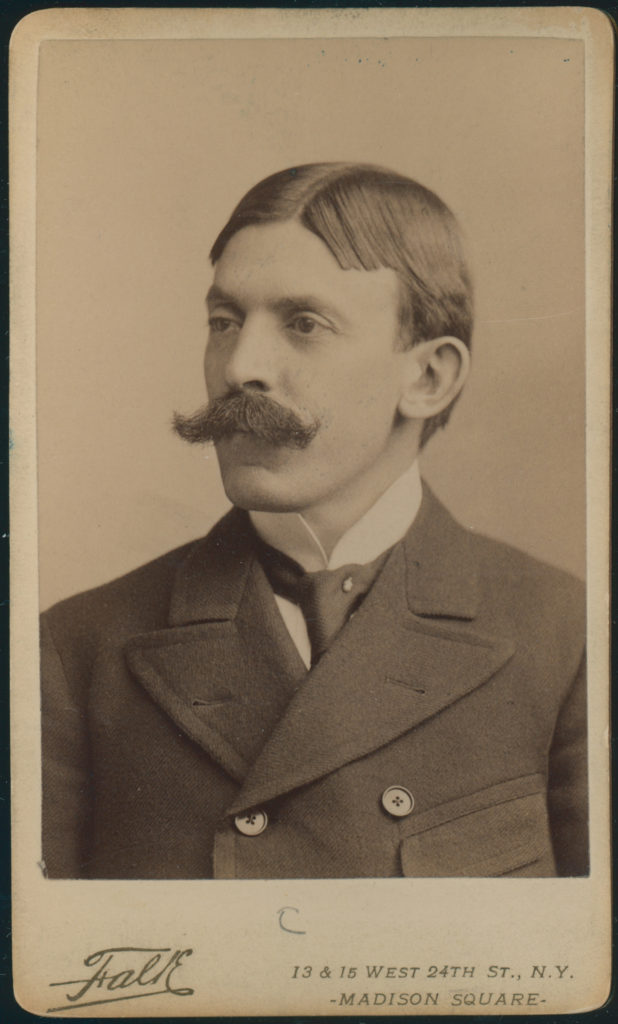

In the early 20th century, New York City had the reputation of being at the forefront of public health efforts. Under the guidance of Dr. Hermann M. Biggs, Commissioner of the New York City Board of Health, it developed several successful public health campaigns. These included clean milk reform, tuberculosis control programs, and immunization drives. Many professionals engaged in the city’s agencies and welfare groups saw these projects as models for programs that could be implemented nationally.Patricia D’Antonio, “Cultivating Constituencies: The Story of the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service, 1928-1941.” American Journal of Public Health. Volume 103 Number 2, pp.988-996; “Dr. Hermann M. Biggs,” American Journal of Public Health (NY). 1923 Sep; 13(9): 760.

In a city that boasted some of the most advanced public health efforts in the country, East Harlem’s high maternal and infant mortality rates were an especially noticeable problem. Mothers had poor prenatal care and suffered from high rates of tuberculosis. East Harlem residents’ poverty meant that many families did not receive medical treatment at all.Patricia D’Antonio, “Cultivating Constituencies: The Story of the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service, 1928-1941.” American Journal of Public Health. Volume 103 Number 2, pp.988-996.

Living Conditions in a Neighborhood of Immigrants

Post-World War I East Harlem was a neighborhood of immigrants. Forty-six percent of the population was foreign born. Another 50% were first-generation Americans, the children of foreign-born parents. Over 70% of the immigrant population came from Italy, and another 23% came from Russia, Germany, and Eastern Europe. Almost a quarter of adults were illiterate. Families lived in tenement apartments of two to five rooms, often with only half of those rooms receiving sunlight. Additionally, on these buildings’ higher floors, residents had limited access to water due to poor water pressure.

Tenement buildings offered scant outdoor space for mothers and their young children to play and get fresh air. The apartments on the buildings’ upper floors had no elevators, making the trip outside with small children difficult. Many young families were isolated, spending most of their time indoors alone. “East Harlem Nursing and Health Service: A Historical Sketch,” East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Pamphlets, 1930-1934, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 1.1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Unifying Services: Caring for the Poor at the East Harlem Health Center

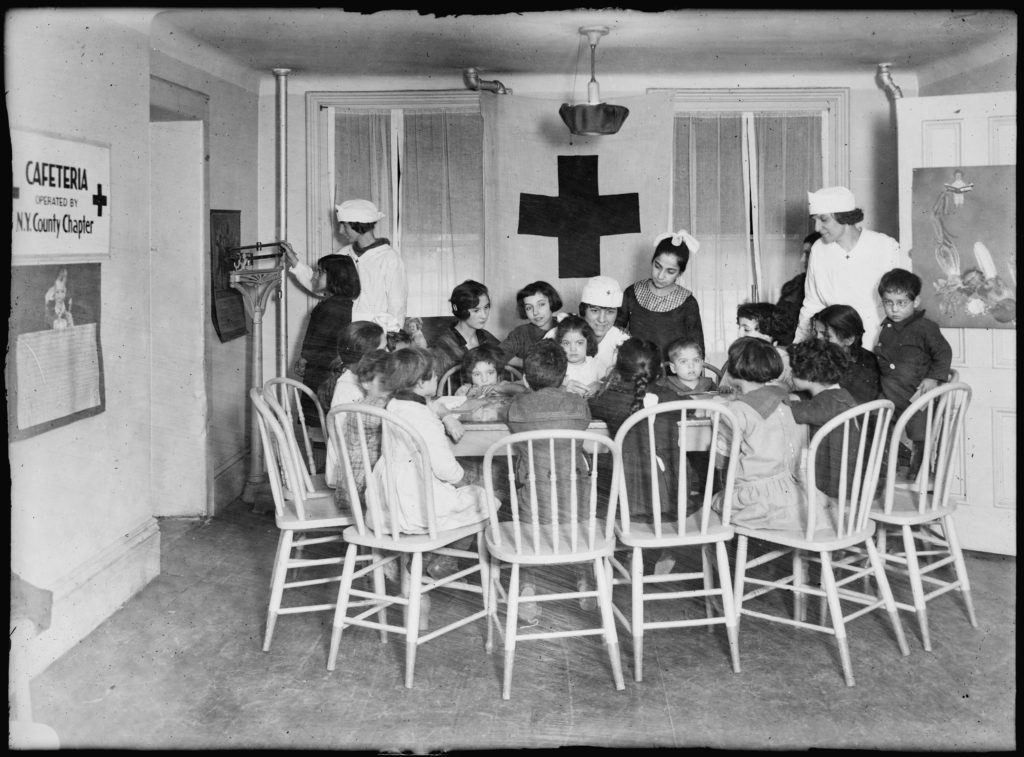

Into the gap of social isolation and lack of healthcare stepped a number of non-governmental agencies, including the American Red Cross (ARC), the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, the Henry Street Visiting Nurse Service, the Maternity Center Association, and the St. Timothy’s League, a volunteer organization of New York-based alumnae of St. Timothy’s School in Maryland. Each organization focused on a different aspect of service provision for the people of East Harlem.“East Harlem Nursing and Health Service: A Historical Sketch,” East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Pamphlets, 1930-1934, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 1.1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

While each organization attempted to improve the lives of the people of East Harlem, there was little coordination among them and no center offering a comprehensive approach to health care and social well-being. Finally, in April 1921, Bailey Burritt, supervisor of health work at the New York chapter of the American Red Cross, contacted the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (LSRM). Burritt requested $30,000 to assist in the creation of a health center in East Harlem, a center that would unite the handful of associations working in East Harlem under one roof and make it easier for clients to get more of their needs met in one location. But equally important, it would create opportunities for collaboration among the organizations themselves, potentially leading to the development of new programs.

The majority of the funding for the East Harlem Health Center was projected to come from the service groups already working separately in the neighborhood, but Burritt reached out to the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial to cover the difference. Established by John D. Rockefeller in 1918 to honor his late wife, the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial supported various charitable causes that had been of interest to her –including the American Red Cross. As the LSRM evolved in the 1920s, it moved from a focus on social work into broader support for the social sciences. During that period, the fund primarily supported well-established institutions and individuals. The East Harlem Health Center’s experimental nature and consortium structure made it an outlier among LSRM grantees.

Cooperation and Collaboration in the Social Services Sector

The organizations at the health center planned to work under a joint administration, with each making a contribution to the costs of operating the center. For example, the Red Cross provided the building as well as funds for its upkeep and the salary of the Director of Nurses. The other organizations contributed the funds for the salaries of the rest of the nursing staff. A robust staff would be necessary because the new Health Center aimed not only to unite existing services, but to create an experiment — a nursing demonstration project.“Health Center to be Established by the Red Cross and Cooperating Organizations,” East Harlem Health Center – Nursing Demonstration, 1921-1928. Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Public Health, Subseries 3_01, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Although the Center was an outlier grantee for the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial in that it wasn’t a solidly established organization (and it certainly was not an elite institution), the demonstration program fit with both the social work and the social science aspects of the LSRM’s mission: supporting the charitable work of known institutions, while using a scientific approach, specifically data collection, to determine the best approaches to public health nursing.“Health Center to be Established by the Red Cross and Cooperating Organizations,” East Harlem Health Center – Nursing Demonstration, 1921-1928, Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Public Health, Subseries 3_01, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Nursing Demonstration: A Model of Urban Healthcare

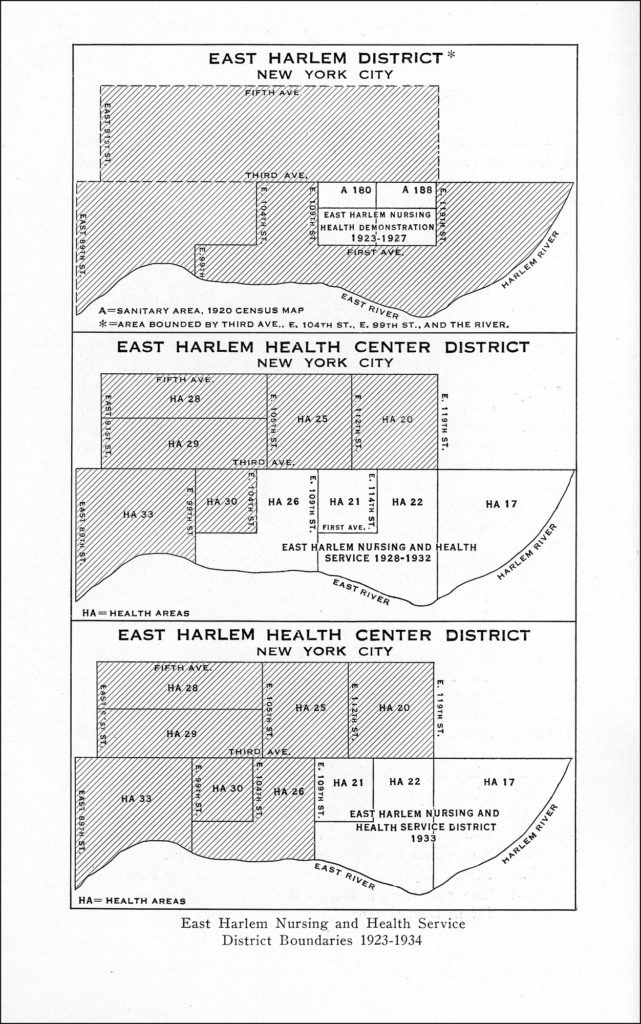

In addition to serving the needs of the area, the nursing demonstration program was meant to showcase the benefits of jointly-run programs and thereby to offer a model for other urban areas. The program focused on a smaller area within the larger district served by the Health Center. Whereas the Health Center itself provided services across some 60 city blocks, running north from 104th Street to 124th Street, and east from 3rd Avenue to the East River, the demonstration district would cover just one portion of that area: 109th to 119th Street between 1st and 3rd Avenues (roughly 20 blocks).“Health Center to be Established by the Red Cross and Cooperating Organizations,” East Harlem Health Center, 1924-1931. Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Public Health, Subseries 3_01, Rockefeller Archive Center.

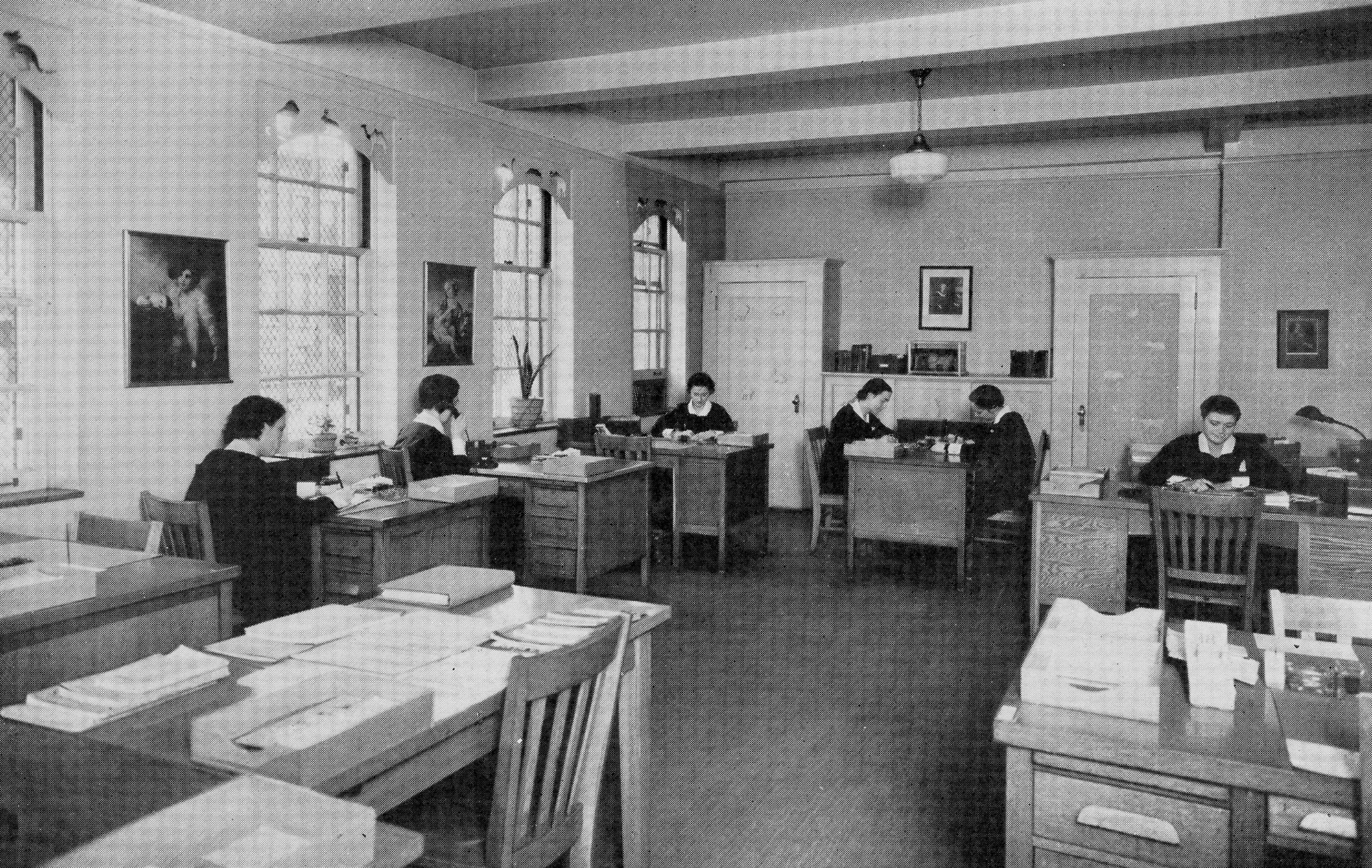

The demonstration consisted of a governing board and a dedicated staff. The board had two members from each main supporting institution and outside experts in medicine, nursing, nutrition, statistics, and education. Meanwhile, the staff consisted of a nursing director, an associate director, four supervisors, twenty nurses/nutritionists, several office assistants, and three part-time physicians.“East Harlem Nursing and Health Service: A Historical Sketch,” East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Pamphlets, 1930-1934, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 1.1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The program targeted maternal and infant care from prenatal care to the child’s entrance into school. The central part of the demonstration effort was the collection of data to better understand two questions about nursing care. First, whether educating parents on general health and well-being during nursing visits, including information on personal and home hygiene, showed any impact on the family’s health. And second, whether nurses trained in general medicine or those trained in specialized fields of nursing provided better patient care.“Resolutions Passed by the Governing Board of the East Harlem Nursing and Health Demonstration, May 11, 1925,” East Harlem Health Center, 1924-1931. Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Public Health, Subseries 3_01; “East Harlem Nursing and Health Service: A Historical Sketch,” East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Pamphlets, 1930-1934, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 1.1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Other than the collection of data in the demonstration, the East Harlem Health Center offered identical programs for the demonstration area and the rest of the district. What set the demonstration apart was its attempt to obtain evidence within its smaller study area that could answer its two key questions. This evidence would eventually help provide better care for all.

How Healthcare Was Provided

Health Center programs were broken into five services. The main one was the Morbidity Service, which provided emergency bedside care. The primary patients were young children (over 45% of cases were children under age five). The Maternity Service was the next-largest focus, providing home care to expectant and recently delivered mothers in the district. The women either came to the service themselves or were referred by a doctor, hospital, or other health agency.

Once children were born, they fell under the care of the Infant Care Health Service. This service cooperated with the Department of Health’s Bureau of Child Hygiene. It included home visits to instruct mothers in childcare, and twice weekly physical exams for children. It also offered classes on nursing and nutrition for the mothers, and provided diphtheria and smallpox vaccines.

The Nutrition Service offered training to the nursing staff, updating nurses on emerging nutritional standards and helping them incorporate nutrition training into their family visits. Finally, the Statistical Service collected data from the daily nursing records.

The nursing demonstration program ran from 1921 to 1925. During that time, nurses visited over 4,000 homes and 13,000 individuals. Half of the home visits were made by the Morbidity and Maternal Services. “East Harlem Nursing and Health Service: A Historical Sketch,” East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Pamphlets, 1930-1934, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 1.1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Evaluating the Pilot Program

The nature of the records kept does not reveal how the families felt about the demonstration program. Nor do we know how they felt about the extra guidance the nurses attempted to impart. What the records do contain is the account of the demonstration project’s board and the lessons it learned from the project.

The board came to two conclusions. First, that immediate medical care was paramount. Only once the most urgent issues had been handled was it worthwhile to educate families on general health and well-being. Nevertheless, the board continued to feel that educating parents on proper hygiene would be crucial to improving the entire family’s health in the long-term.

Second, the data showed that a general practitioner approach was just as effective as deploying specialists, and much more efficient and cost effective. A 1934 report explained,

…with the acceptance of the findings of this study, all home visiting was placed on a generalized basis. We were then able to experiment further in the development of public health nursing from the experience of the nurse as a general practitioner in the health field.

The East Harlem Nursing and Health Service. A Progress Report, 1934.East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Pamphlets, 1930-1934, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 1.1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Impact of the East Harlem Health Center Demonstration

At the end of the demonstration period, the board determined that the program had been a success. The program’s data collection, its main goal, evidenced measurable improvements in health outcomes in the district. For example, tuberculosis morbidity rates decreased from 123 in 1921 to 86 in 1928, even though infection rates remained more or less constant during that period.

The board recognized the limitations on nurses. They could not directly address all of the health needs of the home. Instead, the nurses provided instrumental guidance, informing families about where to look for resources that were available elsewhere, for example classes held at the health center or programs run by the City Board of Health. Nurses could also provide information on appropriate doctors or hospitals to contact. And finally, the board emphasized the importance of outreach to new families beyond those already being treated for health issues.

Expanding the Reach of Healthcare

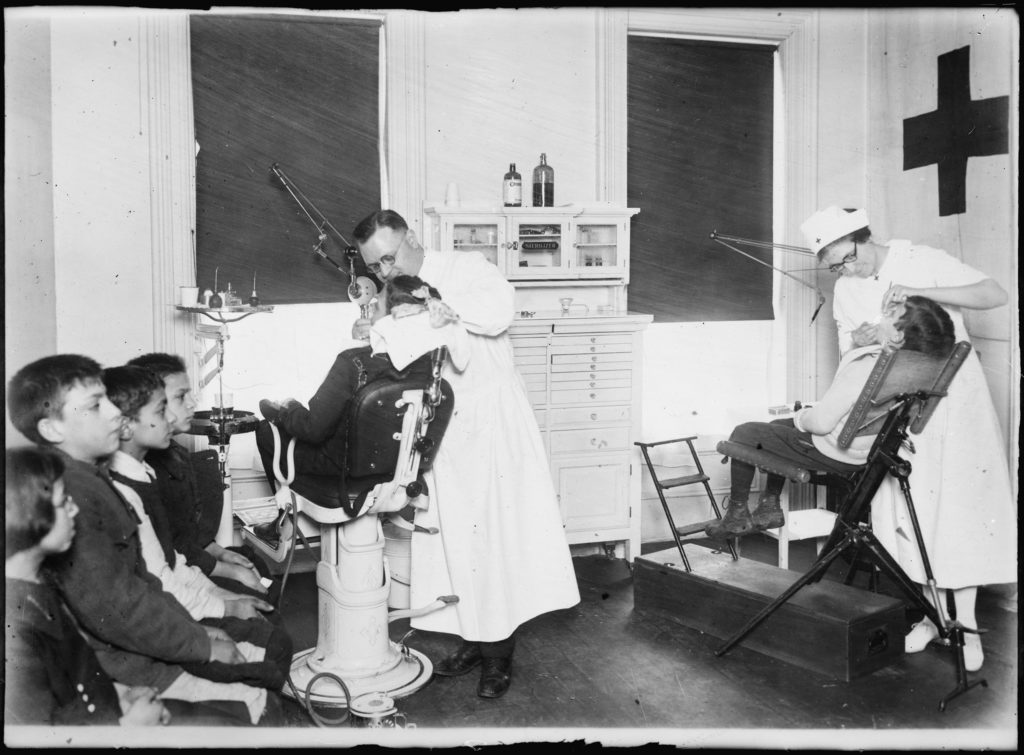

In 1928, the temporary demonstration was made permanent, and given its own name: the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service. The area served was also expanded to the entire 60-block area served by the Health Center. The new East Harlem Nursing and Health Service continued the coordinated services of the demonstration project at a scaled-up level, and added some new, coordinated services as well. These included mental hygiene and dental health programs and a health shop. In the health shop, nurses created visual exhibits to teach about topics such as dental hygiene and cleanliness, using model rooms and homes.“East Harlem Health Center, Activities at the Center Covering the Period of December 1, 1931-April 30, 1932”, East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Pamphlets, 1930-1934, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 1.1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The demonstration board found that the public had a great deal of interest in the program and its services. This was particularly true of students pursuing advanced nursing and public health training. As a result, the board decided to add a teaching program to the work of the health center.

The Educational Component

Nursing students came to the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service from Teachers College, today a part of Columbia University. They applied through personal application and/or recommendation from one of the Health Center’s coordinating agencies. The Center’s Committee on Educational Standards approved each student individually. Students gained field experience by apprenticing in the areas of child hygiene, mental health, nutrition, and social work.“East Harlem Nursing and Health Service: A Historical Sketch,” East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Pamphlets, 1930-1934, Rockefeller Foundation records, Record Group 1.1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

During the transitional time from the demonstration program to the scaled-up East Harlem Nursing and Health Service, the Red Cross began to step away gradually from its previously deep involvement, feeling that the new era signified a new period of stability for the whole East Harlem Health Center. As a parting gift, the Red Cross deeded the Center’s headquarters to the organization.

A New Home for Health Work

The city offered to construct a new building for the East Harlem Health Center. Once that opened, the Center would be able to sell the original building, given to it by the Red Cross, and use the profits to try to become self-sustaining. The Red Cross began the process of turning the building’s administration and program over to other agencies, primarily the Henry Street Nursing Service. With the administrative groundwork set, city officials felt the Health Center could continue on its own.

Tying Off Rockefeller Support

Around the same time, the Rockefeller-funded entities likewise undertook a transition away from supporting the Center. The Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial had supported the Health Center and its demonstration project from 1922 until the Rockefeller Foundation absorbed the LSRM in 1929 (as part of the RF’s 1928 reorganization). When the merger was approved in 1929, the East Harlem Heath Center grant moved to the Rockefeller Foundation’s Division of Social Sciences.

But the retooled programmatic structure of the Rockefeller Foundation after 1928 focused on the advancement of knowledge through research. Both teaching programs and direct service provision fell out of favor. Nevertheless, although the work of the Health Center did not align with the new strategy of the Division of Social Sciences, the Foundation continued to provide funding for about five years. RF staff hoped that would help the Center get onto better financial footing — an achievement they believed would be enabled by the proceeds of selling the original building.

The Health Center Falls on Hard Times

The economic hardship and community suffering brought by the Great Depression thwarted the plans for a robust East Harlem Nursing and Health Service. A 1931 report did show some progress in fundraising, for example, securing $10,000 from the Henry Street Settlement, $1,500 from the Milbank Memorial Fund, and others.East Harlem Nursing and Health Service, 1926-1931. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, Record Group 1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

But the Service and its parent institution, the East Harlem Health Center, began to struggle in the mid-1930s.

Contrary to the hopes of the Red Cross and the Rockefeller Foundation, the Center was unable to reach self-sufficient financial stability. The Great Depression hit the area hard, and even fewer families than before could afford medical care. The Center, with its tight budget, no longer attempted to reach new clients. This, combined with its inability to find financial footing, contributed to its eventual failure to thrive. Another external factor also played a significant part: those women who could afford health care were now mainly choosing hospitals to give birth rather than having in-home births, reducing their need for home nurses at delivery as well as for immediate post-natal visits.

Mission Drift: From Nursing Care to Nursing Education

At the same time, in response to shifting conditions and decreased finances, the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service changed its strategy from direct service provision to becoming a teaching center. Indeed, this turn toward teaching was the main reason why the Rockefeller Foundation would eventually end its funding in 1934.“Letter from Thomas Appleget to Homer Folks, December 26, 1934,” East Harlem Health Center, Inc. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, Record Group 1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

During this difficult period, the East Harlem Health and Nursing Service continued to publish pamphlets on public health nursing that were distributed to health workers around the country, but it was no longer innovating new methods, nor directly assisting the larger East Harlem community. It stopped reaching out to new families and instead focused on families that were already part of its programs.“The East Harlem Nursing and Health Service: Fifteen Years of Cooperative Endeavor: Should It Go On?,” 1937, East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Reports, 1934-1937, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, Record Group 1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Decline of the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service

Despite the several pleas from its director, as well as the unanticipated financial downturn the Service experienced, the Rockefeller Foundation stayed the course and stuck to its initial determination to tie off support. In a December 1934 declination letter to the Center’s director, Foundation Vice President Thomas Appleget explained,

We can understand how present conditions have prevented you from completely obtaining the goal which you set for yourself in 1931. On the other hand, under the limitation of its present program, it is regretted that the Foundation cannot continue its present contributions. Our funds are increasingly required for our regular program, and declinations must frequently be given to very meritorious and appealing opportunities.

Thomas Appleget, 1934“Letter from Thomas Appleget to Homer Folks, December 26, 1934,” East Harlem Health Center, Inc. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, Record Group 1, Series 235, New York – General, Rockefeller Archive Center.

What’s more, while the East Harlem Health Center was still viewed as “meritorious,” the original success of the endeavor had come from its attention to community needs. As the demonstration project, followed by the Nursing and Health Service, shifted focus to nursing education, its mission drifted beyond the community it had been established to serve. As hospitals gained popularity as providers of health services, the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service was no longer the entity best positioned to fill gaps in care.Patricia D’Antonio, “Cultivating Constituencies: The Story of the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service, 1928-1941.” American Journal of Public Health. Volume 103 Number 2, pp.988-996.

In essence, the Center succeeded as long as the demonstration program and its nurses worked cooperatively with the community. But the Nursing and Health Service failed to meet its original goals once it turned inward, reaching out only to members of its own profession.Patricia D’Antonio, “Cultivating Constituencies: The Story of the East Harlem Nursing and Health Service, 1928-1941.” American Journal of Public Health. Volume 103 Number 2, pp.988-996.

The East Harlem Nursing and Health Service finally closed in 1941.

The Legacy of an Experiment in Community-Based Healthcare

While there is still a health center in East Harlem, it is more a reinvention of the original Health Center than a continuation of its early work. Today it is known as the East Harlem Health Action Center, and is part of a network of neighborhood health action centers that has been run by the New York City Health Department since 2016. Much as the East Harlem Health Center did over 100 years ago, today’s Health Action Center unites services from a variety of agencies under one roof, and offers clients both primary health care and referrals, along with wellness education (formerly known in the 1920s as “hygiene”) and support.

Twenty-two private agencies joined with the Health Department—everyone in the district, non-sectarian, Jewish and Catholic, including the health group, the nursing group, and, because of the close relation between sickness and poverty, the welfare group, are solidly behind the Health Center.

Homer Folks, 1924“Letter from Homer Folks to the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, March 4, 1924” East Harlem Health Center, 1924-1931, Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Public Halth, Subseries 3_01, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “East Harlem Health Center,” 1925-1926, Bureau of Social Hygiene records, Projects, Series 3, Juvenile Delinquency, Subseries 3 3, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “East Harlem Health Center,” 1924-1931, Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Public Health, Subseries 3 01, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “East Harlem Health Center – Nursing Demonstration,” 1921-1928, Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Public Health, Subseries 3 01, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “East Harlem Nursing and Health Service,” 1926-1941, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.1, Series 100-257, International and United States, New York, Series 235, General (No Program), Subseries 235.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “East Harlem Nursing and Health Service – Reports,” 1931, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.1, Series 100-257, International and United States, New York, Series 235, General (No Program), Subseries 235.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Henry Street Visiting Nurse Service,” 1892-1946, Simon Flexner papers (American Philosophical Society), Series 1, Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (RIMR), Subseries 1.2, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Henry Street Settlement, Visiting Nurse Service,” 1935-1941, Nelson A. Rockefeller papers, personal papers, Projects, Series L, Rockefeller Archive Center.