In 1933, as fascism descended upon Europe, Rockefeller Foundation leaders found themselves forced to respond to a crisis that challenged their core belief in progress. Between 1933 and 1945, while the European intellectual community was dismantled by the racial and ideological tenets of Nazism, the Rockefeller Foundation responded by supporting and operating a refugee scholar program. Hundreds of scholars and their families were rescued under this program, but its highly selective nature created a complex legacy.

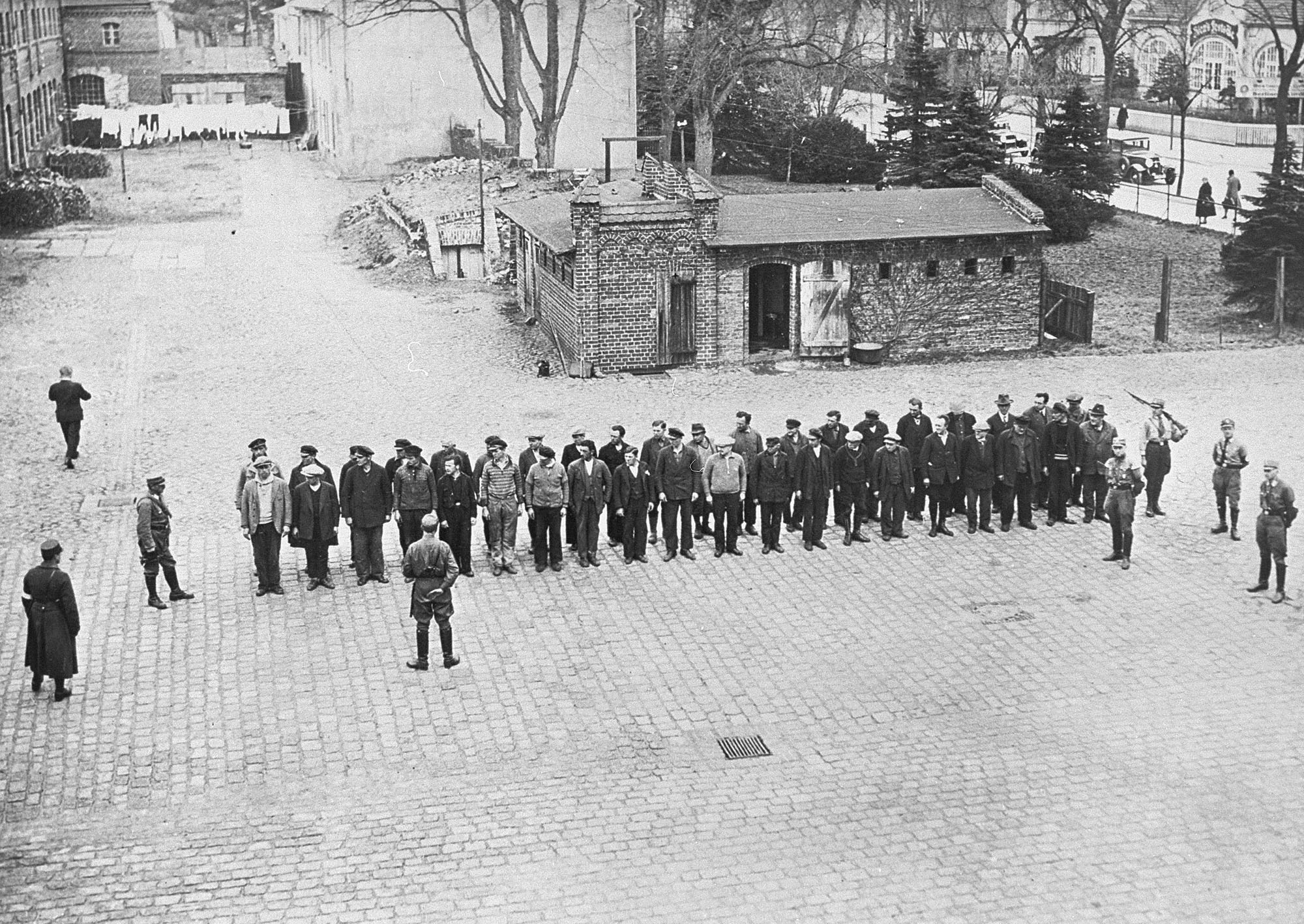

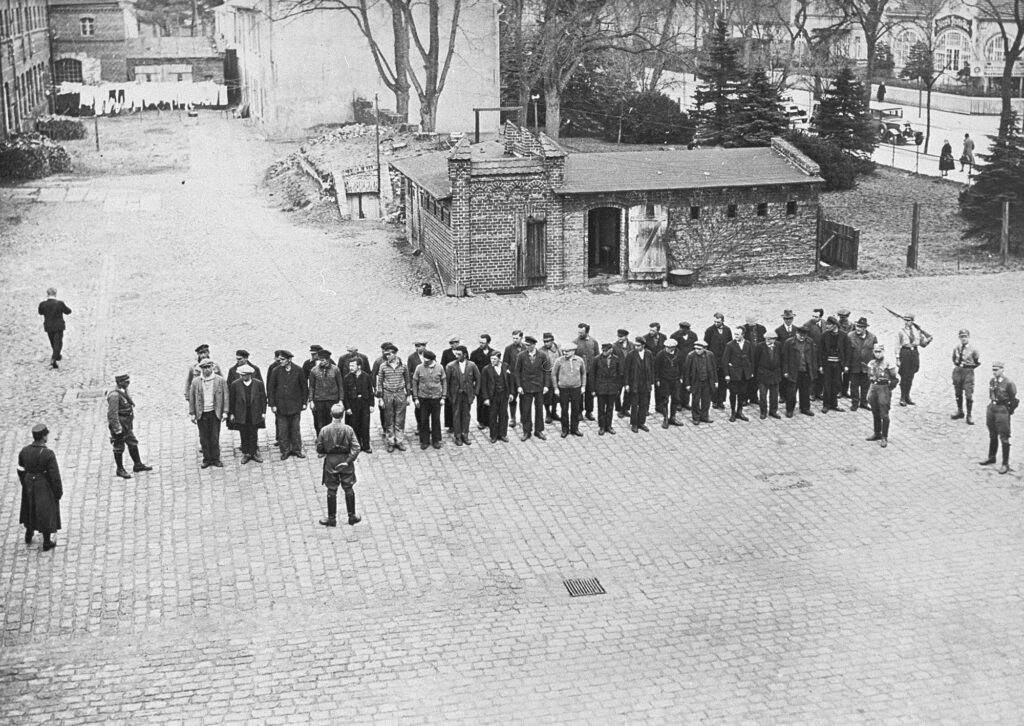

Oranienburg concentration camp on the Havel River in

Germany. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

Special Research Aid Fund for Deposed Scholars

The first program for refugee scholars was initiated in 1933 as the Special Research Aid Fund for Deposed Scholars. This fund set aside money for educational or research institutions in Europe and the United States that were willing to employ scholars who had lost their former positions for religious or political reasons. RF funding typically provided half the cost of a scholar’s salary. This program operated until 1939, aiding mainly German academics. Many notable scholars, including physicist Leo Szilard and novelist Thomas Mann, were assisted under this program. While aid for deposed scholars continued until 1945, by 1940 the rate of funding was slowed when the Emergency Program for European Scholars began.

Emergency Program for European Scholars

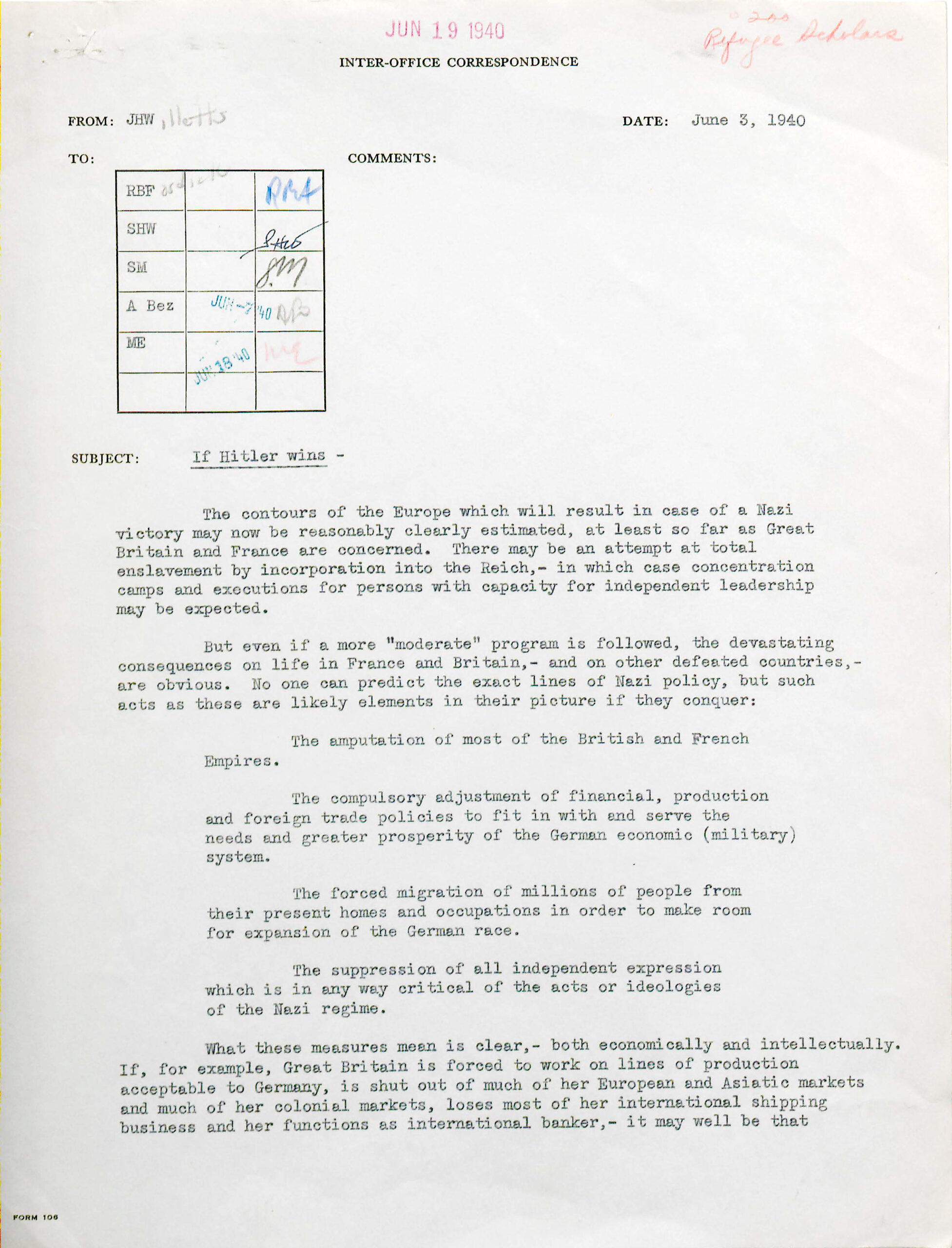

The Emergency Program for European Scholars began when war intensified in Great Britain and Germany invaded France. As circumstances became more dire, RF concerns expanded to include scholars who were in increasingly dire physical danger because of Nazi policies. In June 1940, in a memorandum entitled “If Hitler Wins,” Joseph H. Willits, RF’s Director for the Social Sciences, questioned the role of the Foundation during the crisis. Willits wrote:

With millions of people having to or desiring to migrate from their homelands, the pressure on the Foundation to become a relief body will be terrific. I suggest, – at least so far as SS [Social Sciences] is concerned, – that we choose now as the small part of the total task which the Foundation’s limited resources permit it to undertake, the responsibility for relocating such of the best of the scientific and scholarly men and women from France, Great Britain and other over-run countries as may be available to leave.

Joseph H. Willits, “If Hitler Wins,” June 3, 1940Joseph H. Willits to RF Officers, June 3, 1940, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 1.1, Series 200, Box 46, Folder 530.

Less than two weeks later, following the German invasion of Paris, Willits reiterated his call to action to his fellow Rockefeller Foundation officers.

The program suggested by Willits had a two-fold purpose: to save Europe’s scholars and to improve American scholarship by bringing them to American institutions. In describing this facet of the program, Willits wrote:

I would take the initiative and shop for the best. I would do this cold-bloodedly on the assumption that Nazi domination of these countries make them a poor place for a first-class person to remain in … We could contribute to much needed distinction of our universities by facilitating such immigration.

Joseph Willits, June 3, 1940Joseph H. Willits to RF Officers, June 3, 1940, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200, Box 46, Folder 530.

Throughout the summer of 1940 Rockefeller Foundation officers continued to debate what the Foundation’s role should be. In July 1940 RF Vice-President Thomas B. Appleget suggested that the RF not become directly involved in saving refugee scholars. Appleget argued that such a program would overwhelm the Foundation with requests from scholars and that “[t]here would be inevitable confusion between the hardboiled desire to save intellect and the humanitarian desire to save lives.”Thomas B. Appleget to RF Officers, July 9, 1940, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200, Box 46, Folder 530. Appleget also worried about the ill will that might develop among the European scholars not chosen for the program. In lieu of direct action Appleget recommended a $100,000 appropriation to the Institute for International Education for its program aiding refugee scholars.

There would be inevitable confusion between the hardboiled desire to save intellect and the humanitarian desire to save lives.

Thomas Appleget, July 9, 1940

The debate on the matter continued, and two days later Appleget wrote another memorandum revising his earlier opinion. Appleget noted that after conferring with individuals both inside and outside of the Foundation, “certain personal convictions” had become clear, and he recommended that the Rockefeller Foundation undertake a direct role in an emergency program for refugee scholars. Appleget continued,

There does not seem to be any way in which the Foundation can escape responsibility for decision as to the scholars who are to be aided. There is no other organization so well equipped to select these scholars. Any delegation would be simply a meaningless smoke screen.

Thomas Appleget, July 11, 1940Thomas B. Appleget, July 11, 1940, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200, Box 46, Folder 530.

The resulting Emergency Program for European Scholars involved Rockefeller Foundation cooperation with a number of organizations. Foundation officers worked closely with Alvin Johnson of the New School for Social Research, with whom they had been working since 1933. By 1940 the New School already counted fifty deposed scholars among its faculty and had placed others in various American universities. The RF also depended on the help of the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars to find permanent employment for scholars and the U.S. Department of State to secure non-quota visas for refugees.

Hard Choices

The Emergency Program for European Scholars allocated funds to support one hundred scholars (beyond the over two hundred scholars already assisted by the earlier Deposed Scholar Program). To be accepted in the program, a number of criteria had to be met. Scholars had to:

- Be outstanding in their field

- Be in their productive years

- Have lost their position and generally be considered to be in some danger, whether for religious, racial or political reasons

- Hold the promise of improving existing scholarship in American universities

- Have an assurance of a teaching position for at least two years – this visa requirement also benefitted the Foundation’s financial interests, as scholars without long-term positions would require additional resources.

The strict criteria helped at first but became more difficult to follow as it became clear that those who could not leave might not survive.

Much of the hard work of the Emergency Program was accomplished in the Rockefeller Foundation’s European offices. Foundation officers Daniel O’Brien and Alexander Makinsky remained in Europe and aided fleeing scholars by arranging visas and travel. As the war closed borders and trapped refugees, Makinsky and O’Brien showed a remarkable level of inventiveness and flexibility in their planning.

While they initially worked out of the Paris office, the German occupation of France forced its closure, and operations were relocated to Lisbon. Throughout the course of the war these men faithfully recorded their experiences in their RF Officer Diaries, which now provide fascinating source material on the era.

In the spring of 1942 discussions began on winding down the Emergency Program. On May 11, 1942, Willits wrote:

At no time was the program intended as a relief program, although such considerations have undoubtedly had some weight in particular instances. But the longer the program goes on, the more it tends to take on the character of a relief program. Liquidation of the program as rapidly as is consistent with the achievement of the original objective and the goodwill elements of the situation is, therefore, indicated.

Joseph Willits, May 11, 1942Joseph H. Willits to Roger F. Evans, May 11, 1942, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200, Box 47, Folder 541.

Assessing the Program

The refugee scholar program had its failings along with its success. Critics argued that the program was too limited and elitist and that the RF could have devoted more resources to its operations. However, restrictive immigration quotas in force at the time prevented the Foundation from bringing more scholars to the U.S. Additionally, after its World War I experience, the Foundation had determined not to take on large-scale relief programs. The RF committed itself instead to saving a small group of European academics, whose work had often benefitted from inter-war RF funding initiatives.

Refugee Scholar Stories

The combined Rockefeller Foundation refugee scholar programs ultimately awarded aid to 303 scholars and their families. Among this group were six Nobel Prize Laureates and six future Nobel Prize winners. Eighty-nine of the scholars were part of the later Emergency Program. Fifty-two of these scholars came to America and took up teaching positions, six accepted and spent a portion of their travel grant but ultimately failed to get out of Europe, while a further thirty-one grants were canceled either because the scholar was unable to leave Europe or declined the Foundation’s offer.

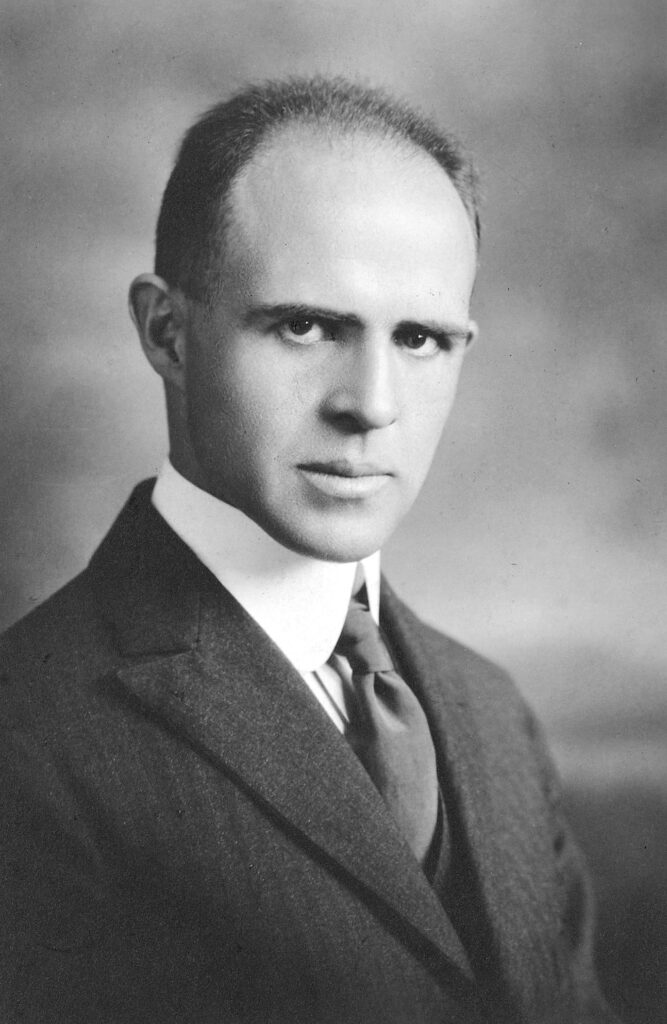

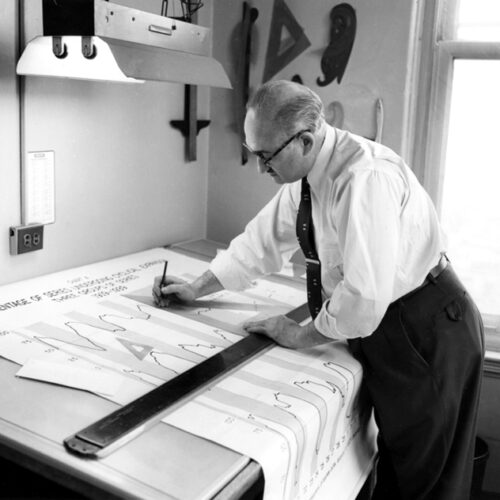

Otto Meyerhof

Otto Meyerhof was a German-Jewish physiologist who had won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1922. In 1938, under Germany’s racial laws that prohibited the employment of Jews as university professors, Meyerhof was forced to resign his position at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. After his dismissal Meyerhof moved with his family to Paris, but following the German invasion of the city in 1940 he wrote to the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) in hopes of finding a way out of Europe.

A Post at the University of Pennsylvania

Given Meyerhof’s academic status and his standing as a Nobel Laureate, a position was quickly secured for him at the University of Pennsylvania in July 1940. Meyerhof spent the next several months encountering roadblocks as he and his family attempted to flee Europe with the help of the RF and various other organizations.

In late July, Alexander Makinsky, working at the RF office in Lisbon, believed that he had secured tickets for Meyerhof on a ship destined for the United States only to have the reservations canceled because of a lack of funds.

Financial Barriers

Frustrated by the financial situation that included inflated prices and black market deals, Makinsky wrote to Alan Gregg describing the reality of trying to secure travel with insufficient funds. Makinsky wrote:

There are 20,000 people here now, all ready to go to America; most of them quite well off; and practically all of them are prepared to pay much more than the actual cost of the ticket (I hope you will understand what that means!) …Those who are paying merely the price of the ticket are already definitely handicapped; and those who, like myself, try to make reservations without paying the full price of the ticket at the time of the reservation is made, have naturally no chance at all.

Alexander Makinsky, July 31, 1940Alexander Makinsky to Alan Gregg, July 31, 1940, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 1.1, Series 200A, Box 113, Folder 1389. Emphasis in original.

Paperwork Difficulties

Meyerhof also struggled with securing the necessary documents. Although American visas were in hand, securing the exit documents from the French authorities proved more difficult. Under the terms of the French-German armistice, no person with German citizenship residing as an émigré in France was authorized to leave the country. Even interventions by Rockefeller Foundation, University of Pennsylvania and US State Department officials failed to secure the necessary papers.

Smuggled to Spain

With all legal means exhausted, Meyerhof sought help elsewhere. With the assistance of the Unitarian Service Committee, Meyerhof and his wife were smuggled out of France and crossed the Pyrenees by foot to arrive in Spain.

At the border the couple was held by Spanish authorities and threatened with deportation before finally being released with the help of the US Consulate.

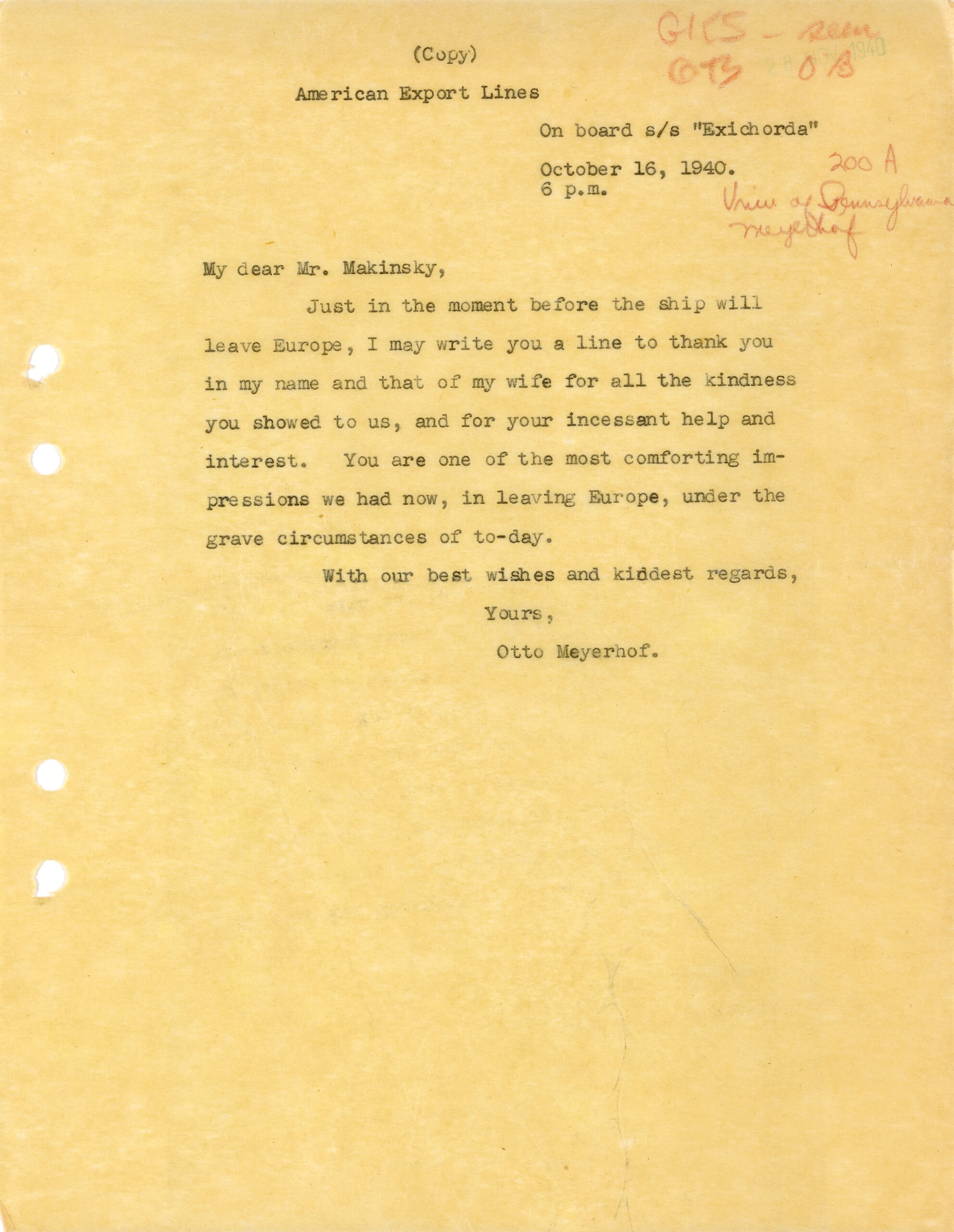

From Spain, Meyerhof and his wife traveled to Lisbon, where they boarded a ship to the United States. On board the SS Exichorda Meyerhof penned a note of thanks to Makinsky, writing:

Just in the moment before the ship will leave Europe, I may write you a line to thank you in my name and that of my wife for all the kindness you showed to us, and for your incessant help and interest. You are one of the most comforting impressions we had now, in leaving Europe, under the grave circumstances of today.

Otto Meyerhof, October 16, 1940Otto Meyerhof to Alexander Makinsky, October 16, 1940, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200A, Box 113, Folder 1390.

Meyerhof arrived in the United States in October 1940 and took up a position at UPenn. Following the war he remained in the U.S., and he died in Philadelphia in 1951.

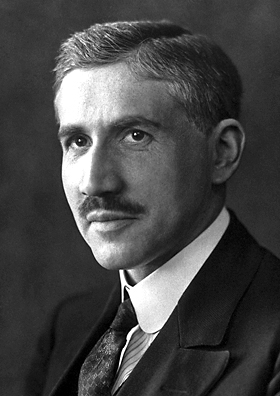

Marc Bloch

Marc Bloch, who taught at the Sorbonne and founded the Annales School of historical analysis, was one of the world’s leading economic historians when he left his professorship to become a captain in the French Army at the outbreak of World War II.

Analyzing and Experiencing the War in Real Time

Following the French surrender in 1940, Blosh wrote L’étrange Défaite (Strange Defeat, published 1946). In it, the historian argued that the French defeat was the culmination of years of ineffective leadership, a failure to keep up with war technology, and interwar ideas and culture.

Based in part on his own Jewish origins, Bloch sought refuge for himself and his family in the US. Writing on his behalf, Professor Earl J. Hamilton of Duke University wrote:

I believe that M. Bloch’s presence in this country would tend to raise the level of scholarship in economic and social history. I fear that he is in a precarious position in his native country. Assistance from the Foundation in reaching America and living until he can secure a foothold would not only be an act of charity and brotherly love but it might be instrumental in saving from destruction a fertile, energetic, and original mind.

Earl Hamilton, October 13, 1940Letter from Earl J. Hamilton to Joseph H. Willits, October 13, 1940,RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200, Box 48, Folder 550.

Aid Granted

In October 1940 Bloch was invited to become a part of the Emergency Program for European Scholars.

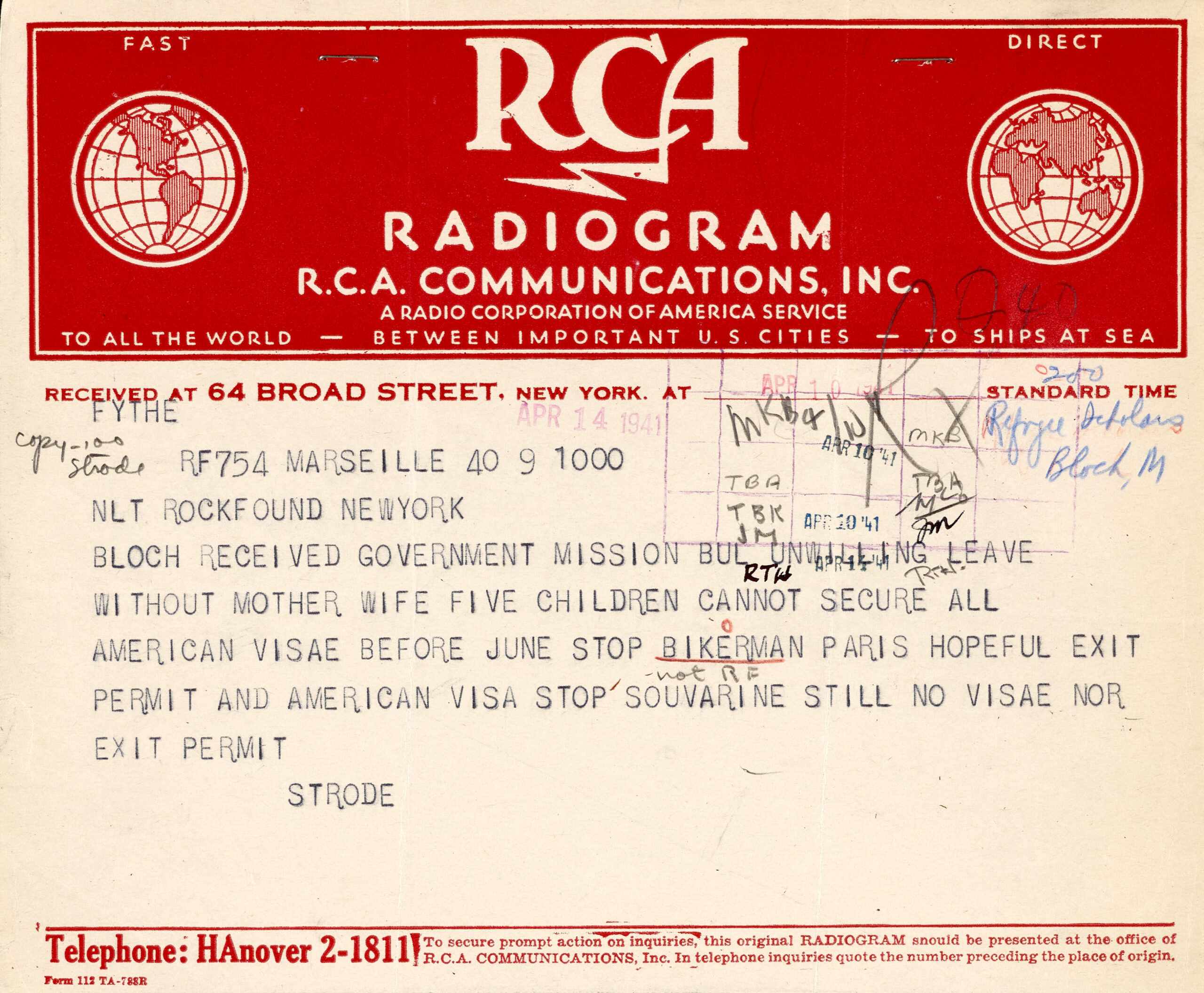

In April 1941 word reached Bloch that American visas had been secured for him, his wife and four of his six children. He was told that visas for his two eldest children would be forthcoming in June. With news of the progress, Makinsky, working from the Rockefeller Foundation’s temporary headquarters in Lisbon, set about arranging travel for the first group to leave.

Unwilling to Leave Without Family

But Bloch refused to leave without his family. He wrote to Makinsky informing him that he and his wife felt it impossible to travel without their remaining children.

Aware of the difficulties in securing travel out of Europe in 1941, Makinsky wrote of Bloch’s decision,

I am completely out of sympathy with B.[loch], as unless he is willing to wait until the late fall, he will never be able to get eight places on the same boat.

Makinsky, April 28, 1941Excerpt from Makinsky Letter, April 28, 1941, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200, Box 48, Folder 550.

In 1941 the French government passed a law prohibiting French males between the ages of eighteen and forty years old from leaving Paris. Bloch’s eldest sons fell under the new law. On July 31, 1941, Bloch wrote to Alvin Johnson at the New School for Social Research, updating him of the situation and informing him that he and his wife felt that they could not leave their sons behind.

Bloch went on to express his uncertainty over the future, writing that,

Nobody may foresee whether the present legislation, as to the leaving of the French territory, will last or no: at least, with the same strictness. It will depend on the circumstances, interior and exterior. The fate of those people who, like us, are falling under the so-called racial laws is equally uncertain.

Marc Bloch, July 31, 1941Letter from Marc Bloch to Alvin Johnson, July 31, 1941, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200, Box 48, Folder 550.

A Tragic End

Bloch’s decision to remain in France proved fatal.

Bloch remained in France and joined the French Resistance in 1942. In June 1944, Bloch was captured and shot by the Gestapo.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “Refugee Scholars,” 1936-1940 November. Rockefeller Foundation records; Projects (Grants) – Record Group 1; Subgroup 1.1; International and United States – Series 100-257; United States – Series 200; General (No Program) – Subseries 200.GEN; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Refugee Scholars,” 1940 December-1963. Rockefeller Foundation records; Projects (Grants) – Record Group 1; Subgroup 1.1; International and United States – Series 100-257; United States – Series 200; General (No Program) – Subseries 200.GEN; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Refugee Scholars – New School for Social Research,” 1940. Rockefeller Foundation records; Projects (Grants) – Record Group 1; Subgroup 1.1; International and United States – Series 100-257; United States – Series 200; General (No Program) – Subseries 200.GEN; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Refugee Scholars – Bloch, Marc – (Economic and Social History),” 1940-1942. Rockefeller Foundation records; Projects (Grants) – Record Group 1; Subgroup 1.1; International and United States – Series 100-257; United States – Series 200; General (No Program) – Subseries 200.GEN; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of Pennsylvania – Meyerhof, Otto – (Refugee Scholar, Physiology),” 1940-1951. Rockefeller Foundation records; Projects (Grants) – Record Group 1; Subgroup 1.1; International and United States – Series 100-257; United States – Series 200; Medical Sciences – Subseries 200.A; Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.