Environmental education, a now widely accepted strategy of the modern environmental movement, was once a new idea. Its origins trace partly to a series of grants totaling nearly one-million dollars given by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund (RBF) to the National Audubon Society (NAS). The grants, disbursed over the 1960s and 1970s, enabled NAS to launch its pioneering Nature Centers Division. The centers that the NAS opened across the United States helped to build public support for conservation, outdoor recreation, and ecological research. By funding the development of these centers, the RBF hoped to improve the nation’s environmental awareness. In the end, the grant also played a key role in transforming Audubon into a more modern conservation organization, as the new education programs helped keep the nearly 100-year-old organization relevant in a changing environmental context.

“National Audubon Society’s Condensed Proposal for Expanded Services,” October 1964

The RBF helped the Audubon Society transform from an organization concerned with ‘the protection of birds to one endeavoring to broaden the conservation ethic of the American people.’

The Audubon’s Early Focus

The evolution of the Audubon Society into a modern conservation organization did not happen overnight.

Established in 1905, the NAS emerged out of a late-nineteenth century movement to protect bird species threatened by the millinery industry, and loose plumage and game laws. While the Society developed Junior Audubon Clubs with funding from the Russell Sage Foundation in the 1920s and opened its first nature center in Greenwich, CT in 1943, the organization’s early mission nevertheless centered on wildlife conservation.

It was not until the NAS merged with another organization — the National Foundation for Junior Museums (NFJM) — that the Society became a true leader in the field of environmental education.

Nature Centers as a New Fulcrum

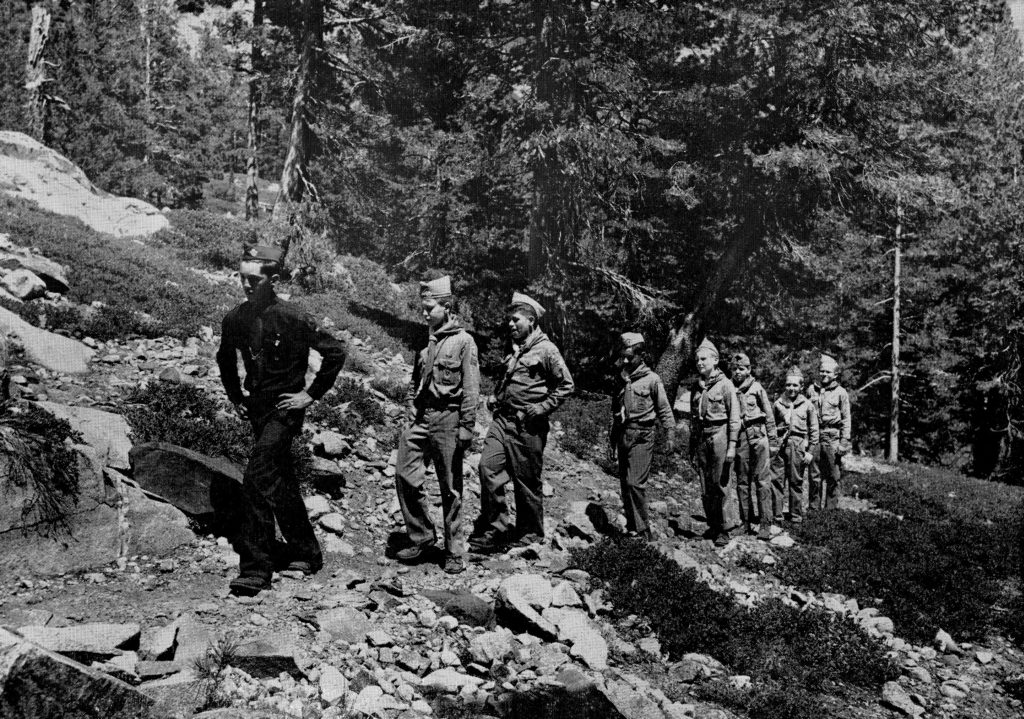

Established in 1944, the NFJM provided local communities with the expertise and logistical support to develop new nature centers.

Typically comprised of a large swath of natural land and a museum or educational facility, these centers aimed to provoke a deeper interest in — and understanding of — the natural world. In the long-term, the NFJM saw the nature center concept as the fulcrum of a new type of environmental movement in the US, one that not only conserved natural areas through governmental and philanthropic initiative, but also made Americans more interested in conserving land themselves.

Driving Forces

The driving force behind this mission was the NFJM’s longtime director, John Ripley Forbes, who is today considered the father of the nature center movement. A lifelong conservationist, Forbes devised an amateur animal exhibit in his attic at a young age that caught the attention of his neighbor, William T. Hornaday, the first director of the Bronx Zoo, and eventually became a permanent exhibit at a local Connecticut museum.

After studying zoology and ornithology at Iowa State University, Forbes founded the William T. Hornaday Foundation in 1937, a precursor to the NFJM, to honor his neighbor. Today, Forbes is credited with creating junior nature centers in over 200 communities and is commemorated by a thirty-acre forest, the John Ripley Forbes Big Trees Forest Preserve, in Sandy Springs, Georgia, which he helped establish in the late 1980s.

Accomplishments

Under Forbes’ watch, the NFJM became a pioneer in the field of conservation education. By the late 1950s, the organization had utilized a $250,000 grant from the Fleischmann Foundation and several smaller grants from the Old Dominion and Sloan Foundations to create twenty-five different nature centers in the U.S., mostly in the West and Southwest. According to some reports, this figure represented a sizable portion — between fifteen and twenty percent — of all centers in the country.Doris Gross to General RBF Files, “National Foundation for Junior Museums, Inc.,” October 11, 1956, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center; Dana S. Creel to Laurance Rockefeller, December 17, 1958, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

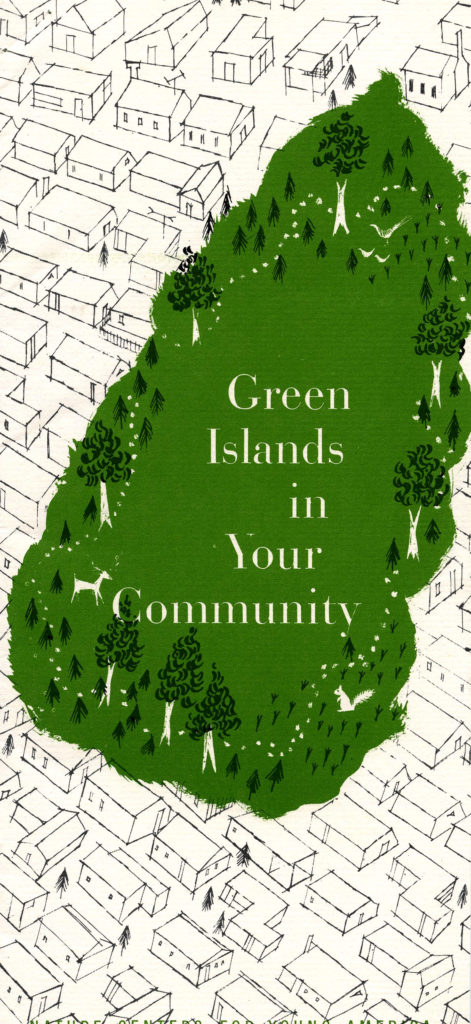

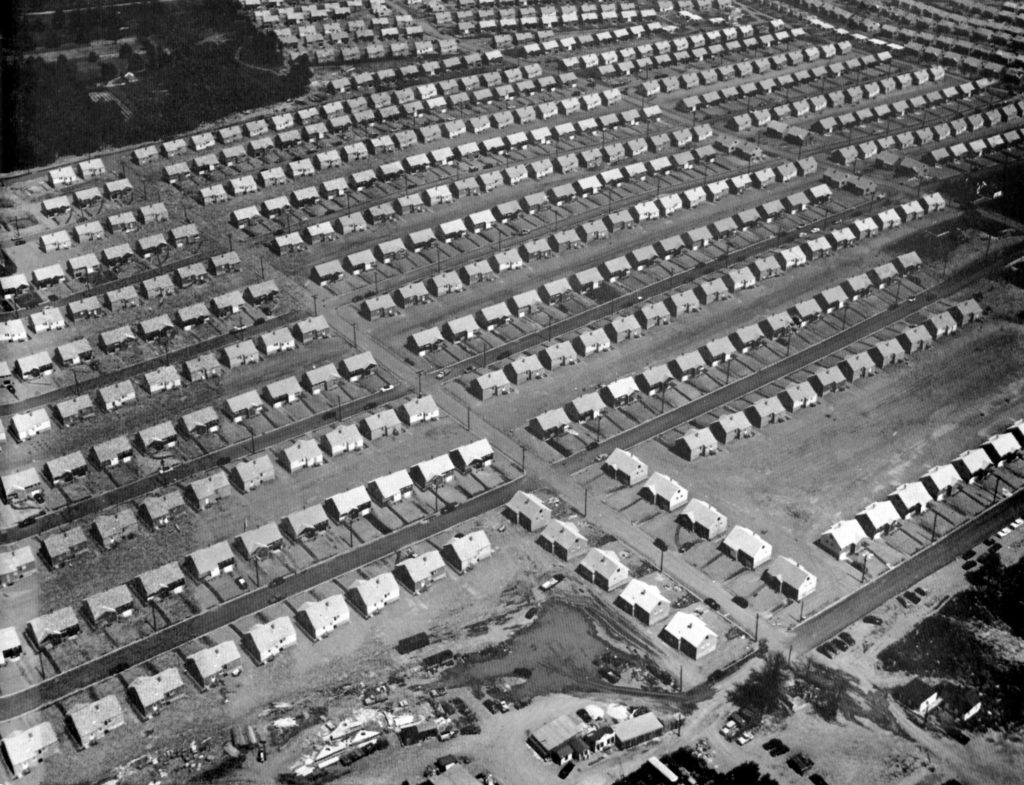

Room for Growth

Despite these achievements, however, the NFJM wanted to expand its services. The organization’s primary goal was to develop new programs in the East, where urbanization and suburban growth continued to encroach on natural land. The Foundation saw nature centers — or “islands of nature” as it called them — as buffers against this onslaught.

Creating new nature centers would require the Foundation to elevate its local outreach and fundraising strategy.

To date, John Ripley Forbes, the NFJM’s renowned director, had handled these duties. But despite his enthusiasm and deep knowledge of environmental education, Forbes needed help. For the past decade or so, the director had in essence run the NFJM himself. A board existed more or less in name only and the Foundation (or rather Forbes) performed outreach on an ad hoc basis.

As a result, the Foundation never fully developed a sustainable system of operation. One external review in fact concluded that the NFJM was “never a really effective administrative unit,” “lacked real direction,” and “lived a more or less hand-to-mouth existence from day to day.”

Acknowledging these shortcomings, NFJM leaders sought assistance from a larger nonprofit to hire more staff, strengthen the Board of Directors, and develop a more robust fund-raising strategy.“National Foundation for Junior Museums: Its History, Philosophy, and Program,” September 1958, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Audubon Society would eventually become this nonprofit. But first, the NFJM sought help from another organization committed to environmental conservation: the Rockefeller Brothers Fund (RBF). Driven by the growing interest of its president, Laurance S. Rockefeller, in environmental education, the Fund played a pivotal role in expanding NFJM programming and, in turn, laying the groundwork for the Foundation’s merger with the NAS.

Getting a Boost from a Big Environmentalist

Rockefeller expressed great interest in the NFJM proposal when the organization approached the RBF for support.

He had made regular contributions to both the William T. Hornaday Foundation and NFJM since the 1940s, and, by the late 1950s, had become keenly interested in building the field of conservation education.

By this time, Rockefeller’s credentials as a leading environmentalist were already well-established: he held top positions on the Palisades Interstate Park Commission (PIPC), served as chairman of the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC), a body created by President Eisenhower to assess the country’s outdoor recreation needs through the year 2000, and in 1960 began work as Vice Chairman of the New York State Council of Parks under Robert Moses.

Over the course of his career, Laurance Rockefeller also helped establish and develop several national parks, including the Virgin Islands National Park, the Marsh – Billings – Rockefeller National Historical Park in Vermont and a portion of Grand Teton National Park, and became renowned for building several eco-friendly hotels on the United States mainland, as well as in Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Hawai’i.

Rockefeller Brothers Fund Supports Conservation Education

Sensing that RBF funds could make a significant impact in the nascent field of conservation education, Rockefeller asked RBF staff to explore the possibility of supporting the NFJM in 1958. In November of that year, the Fund’s board agreed preliminarily to provide the Foundation with $100,000 over three years to expand its programming.“Discussion Paper: Conservation — Public Use of Conserved Resources,” Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Eager for RBF funding, the NFJM agreed to create a new executive director position tasked with implementing this new strategic plan and change its name to “Nature Centers for Young America” (NCA) in the hopes of signaling a broader — and less museum-centric — mission.“Memorandum of Conference at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, January 7, 1959,” Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center. Dana S. Creel to Laurance Rockefeller, December 17, 1958, Rockefeller Brothers Fund, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Shortly thereafter, the Fund appropriated $25,000 to the renamed NCA, the first of three payments from 1959-1961 that would ultimately total $100,000. With these funds, the NCA created a development department to promote the organization’s work, conducted local outreach, and launched eight new projects on the east coast.“Minutes of Meeting of the Executive Committee,” February 13, 1959, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1 Rockefeller Archive Center; NCA Promotional Material, “What We Have Accomplished – April 1960,” Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

As one NCA report concluded:

We are more than ever convinced that we are on the right track, and that the nature center idea will develop and spread throughout the country.Erard A. Matthiessen to NCA members, June 30, 1960, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

A Merger Enables Twice the Influence

This prediction proved correct. In 1961, the NCA, with RBF support, made nature centers a mainstream facet of the modern environmental movement by merging with the Audubon Society.

The merger made sense for both organizations.

From the NAS perspective, the NCA would help the Society continue its recent efforts to move into other fields of environmental conservation beyond bird protection.

From the 1930s to the 1950s, the Audubon Society had indeed begun to focus on preserving other forms of wildlife and natural habitats. To implement this broader mission, the NAS established several additional nature camps and centers throughout the country (in addition to the Society’s first one in Greenwich, CT, established in 1943).

In subsequent decades, the Society also became a chief advocate for important new environmental laws, including the Clean Air and Water acts and the Endangered Species Act.

These new activities signaled the birth of a larger, and far more multi-faceted NAS. Indeed, the organization established several new regional offices and saw its membership more than triple in the 1960s and 1970s. The creation of a new Nature Center Division would allow the Society to continue developing more robust programming across the country.

For the NCA, folding into the Audubon Society offered several perks as well: more funding, more national exposure, and a kind of logistical support only a large-scale organization could offer.

For these reasons, Laurance Rockefeller all-but-guaranteed more RBF funding if the organization merged with the Audubon Society. As he told Erard Matthiessen, an NCA leader who later served as Vice President of the Audubon Society, in January 1961:

“Should the Society and Nature Centers join forces, I can see no reason for a diminution of interest by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. Quite the contrary…the Fund’s trustees quite logically would have even greater confidence in the undertaking.” Laurance Rockefeller to Erard Matthiessen, January 16, 1961, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Widespread Acceptance for Nature Centers

The two nonprofits – their missions increasingly aligned – officially merged in July 1961. In turn, Audubon created a Nature Centers Division that would help expand the Society’s local youth programming.National Audubon Society – Nature Centers Division Grant Report, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The RBF followed suit with a series of several significant grants to the Audubon Society to strengthen its educational programming — $100,000 from 1961-1964, $300,000 from 1965-1969, and another $400,000 from 1970-1974. All told, the RBF supplied the NAS with $800,000 (over $5 million in current dollars) over this decade-plus long period.Excerpt from Minutes of RBF Trustee Meeting, November 16, 1961, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center; National Audubon Society Grant Report, November 19, 1964, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center; Excerpt from Minutes of RBF Semiannual Meeting, November 20, 1969, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

This support not only helped the Society become a leading nature center sponsor, but also made nature centers a regular feature of American communal life. As one report concluded:

Few knowledgeable people snicker anymore when a nature center is…proposed in a community.“Nature Centers Come of Age: A Twelve Year Report of the Work and Accomplishments of the Nature Center Planning Division of the National Audubon Society,” Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Audubon Society Transforms

This support also helped the Audubon Society broaden its entire mission and undertake more grassroots work.

By the early 1970s, the NAS had become the nation’s largest direct membership environmental organization, with a budget of $3.5 million and a portfolio of over fifty projects. It also launched a new newsletter, a training program for students and recent graduates, and a mass advertising campaign. Thanks largely to these activities, the Audubon Society had preserved roughly 350,000 acres of land for nature centers; all told, there were over 800 junior nature centers in the U.S. by this time. As a result, conservation education became a core component of the American environmental movement.National Audubon Society Grant Report, November 20, 1969, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center; “Progress Report on Rockefeller Brothers Fund Grant,” Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center; “Nature Centers Come of Age: A Twelve Year Report of the Work and Accomplishments of the Nature Center Planning Division of the National Audubon Society,” Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The RBF played a vital role in this transformation, supporting the NCA/NFJM and its incorporation into Audubon just as the Society sought to broaden its mission and expand its work in local communities.

As one review aptly noted, the RBF helped the Audubon Society transform from an organization concerned with “the protection of birds to one endeavoring to broaden the conservation ethic of the American people.”“National Audubon Society’s Condensed Proposal for Expanded Services,” October 1964, Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “Philanthropies – National Association of Audubon Societies,” 1910-1915, Russell Sage Foundation Records, Subgroup 1, Mrs. Russell Sage, Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Massachusetts Audubon Society, Inc. (06600146),” 1966-1970, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants L-N, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “The National Audubon Society (06600419),” 1966-1968, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants Them-Tw, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Audubon Society – Nature Centers Division,” 1960-1971, David Rockefeller papers, Rockefeller Family and Associates (Room 5600), General Files, 1962-1996, 1962-1976, RG3, Record Group 3, Conservation Series, A-Z, Subseries 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Northeast Illinois Natural Resource Service Center (07000429),” 1970-1972, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants L-N, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “The politics of saving nature: An assessment of the performance of the Conservation Service Center of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, Oct. (Reports 002297),” 1969, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 1-3254, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Audubon Society,” 1975-1986, Charles E. Culpeper Inc. records, Accession 2, Record Group 2, Grants, Series 3, General Grants, Subseries 5, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Water Pollution (Federal Activities) – 1970 Clean Air Act (PL91-604, December 31, 1970),” 1970, Nelson A. Rockefeller papers, Nelson A. Rockefeller Vice Presidential records, National Commission on Water Quality, Series 9, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Related

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Creates a National Park

Who defines the public good? The showdown caused when a wealthy philanthropist bought land and tried to give it to the American people.