At the turn of the twentieth century, industrialization and urbanization brought an increase in infant mortality to vulnerable New York City populations. The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research targeted this problem in its first programmatic action — a survey of the city’s milk supply. The research findings would spark public outcry, the creation of a new city inspection program, and by 1906, would inform federal food safety policy.

New York City at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

The rise in industrialization, urbanization, and immigration around 1901, and the growth of America’s cities, including New York, brought many benefits, but also difficulties. With so many people moving to cities, there was a need for more places to live. Cities quickly built tenement buildings to house these new, often poor residents. Because of the speed in construction, tenements lacked infrastructure including adequate plumbing and ventilation. This prompted an increase in disease within a population unequipped to deal with it.

Infection rates of cholera, typhoid, dysentery, and infant mortality among the poor in New York increased significantly during this time.

The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research

The establishment of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (now Rockefeller University) was, in part, a response to these contemporary public health crises. John D. Rockefeller established the Institute in 1901. It was the first institution created by Rockefeller philanthropy to carry the Rockefeller name, and the first American institute dedicated solely to medical research. The Institute focused scientific investigation on public health problems, especially diseases such as yellow fever, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and poliomyelitis. Rockefeller gave an initial endowment of $200,000.Endowment letter, June 14, 1901, Series O-Rockefeller Boards, Office of the Messrs, Rockefeller Family Papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

With the endowment in hand, a newly formed Board of Scientific Directors, the Institute’s governing body, began its work. Initially, the Board gave grants and fellowships to scientific investigators already working in the field. About fifteen years later, the Rockefeller Institute began direct operation of its own research programs.

The Milk Survey Grant Tackles Infant Mortality

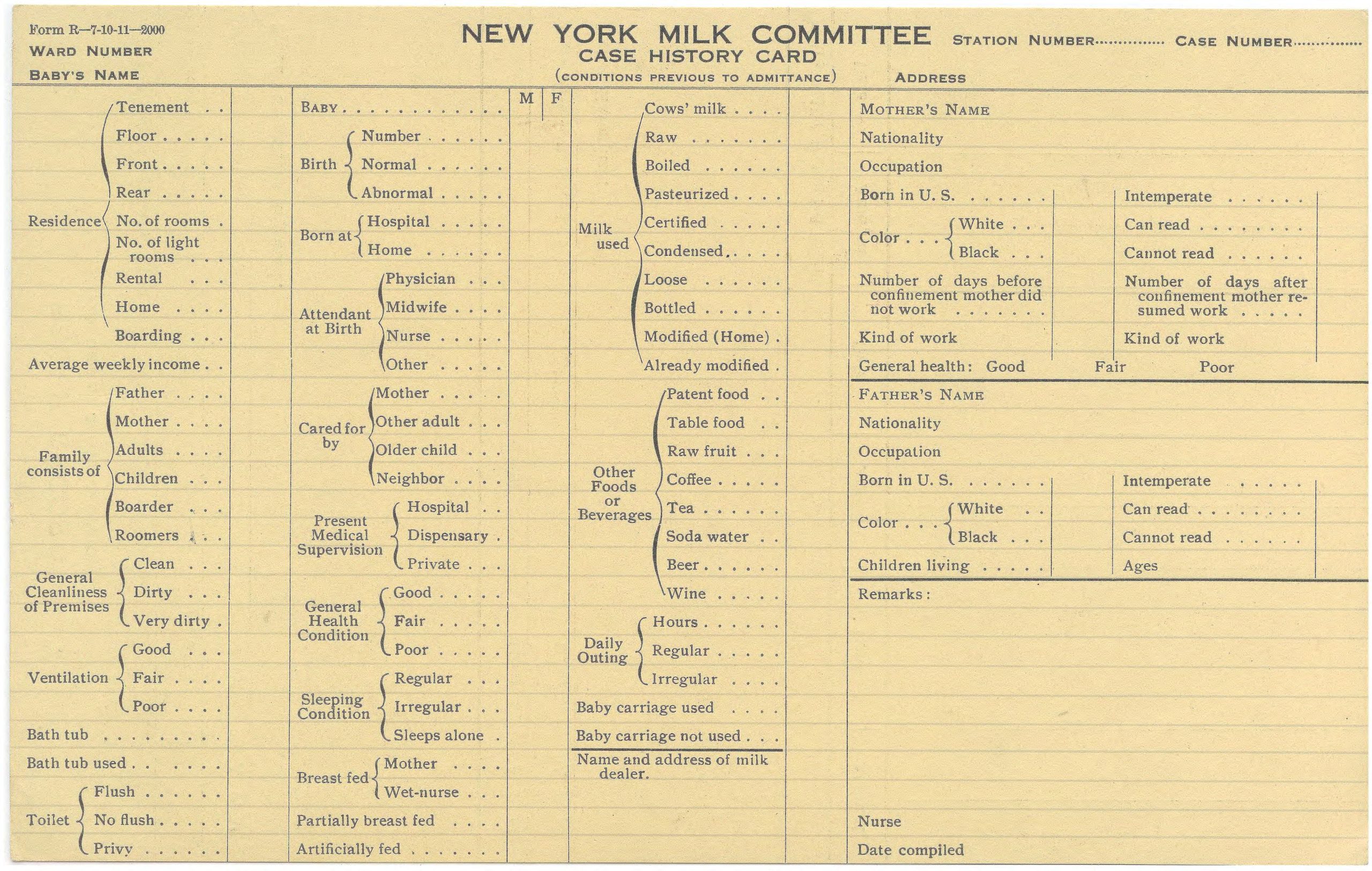

Among the members of the Board of Scientific Directors was Dr. Hermann M. Biggs, Commissioner of the New York City Board of Health. Through his work leading the Board of Health, Dr. Biggs was well aware of the high levels of infant sickness and death. These problems were linked to the city’s contaminated milk, and this was particularly true in the tenement districts. The New York City Board of Health had already conducted a study of milk quality. However, that study left gaps because it only measured quality at delivery.

This new survey hoped to examine the conditions where the milk was produced and bottled. It would also examine the infants drinking the milk, to establish any connection between the milk supply and infant mortality.

The Rockefeller Institute’s Board approved an initial grant of $2,400 to the New York City Board of Health in May 1901. The grant funded a survey of both milk transportation and distribution and the relationship of these two factors to the health of children, particularly infants. The grant provided for several staff positions to inspect dairies and creameries, tenement homes, and children’s hospitals. The support also provided funding for the establishment of a laboratory at the Board of Health. The lab’s bacteriologist and biochemist both received their salaries from the grant.Minutes, May 25, 1901, RG 110-2, Minutes of the Board of Scientific Directors, Rockefeller University Records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Aiming to Understand Milk Quality

The milk survey began in earnest in June 1901, and encompassed five areas of examination:

I. The sanitary conditions of the farms and creameries supplying the city with milk.

II. Railway transportation and city delivery.

III. The condition of the milk on delivery, as to the number and variety of bacteria present.

IV. The effect of milk of various degrees of purity upon the health of infants and young children in institutions and tenements during the hot weather.

V. A more definite study of the changes occurring in milk which cause disease.

VI. To what degree both the dealer and the farmer could be depended upon for voluntary cooperation in improving the milk supply.“The Milk Supply of New York, Some of the Facts Brought Out by the Investigation of the Rockefeller Institute”, Rockefeller Institute – Milk Supply, 1901-1902, Series O-Rockefeller Boards, Office of the Messrs., Rockefeller, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Milk Supply Chain: Site Visit Reports

The first step of the investigation was to determine which farms and dairies supplied milk to New York City. According to a report from one of the scientific directors, the city received over 1.5 million quarts of milk daily. Some milk came from farms as far as 300 miles away, within five different states.“The Milk Supply of New York, Some of the Facts Brought Out by the Investigation of the Rockefeller Institute”, Rockefeller Institute – Milk Supply, 1901-1902, Series O-Rockefeller Boards, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Farmers sent their milk to creameries instead of selling it directly. Creameries received milk from up to 20 or 30 farms at a time. The creameries then sent the milk to stations, hospitals, and groceries throughout the city. The investigators surveyed the farms, creameries, and transportation locations. They aimed to accomplish their work with voluntary cooperation from the owners. In turn, the owners hoped the attention brought by the investigation would improve their business. Yet the news from the survey was not always positive, and the investigators, in fact, found a wide range of conditions at each stage of the process.

Appalling Health and Hygienic Conditions

Even the best locations in the supply chain had room for improvement. For example, hand washing by dairy staff was often insufficient. At the other end of the spectrum, the worst conditions could be described at best as appalling. One particular offender was a milk depot in New Jersey that distributed over one hundred quarts daily to districts throughout the city.

According to the survey report, the New Jersey milk depot stored the incoming milk in three cooling vats located in a converted stable. The stable’s floor was made of partly packed earth and the milk storage room was unclean. Splatter from the vats accumulated on the ground. Dust, dirt, and cobwebs covered the ceilings and walls. The milk cans were cleaned without soap in only lukewarm water, if they were washed at all. Worst of all, the milk cans sat next to the dirty water disposal and staff latrines. The creamery did not clean the milk cans before they were sent back to the dairies.“The Milk Supply of New York, Some of the Facts Brought Out by the Investigation of the Rockefeller Institute”, Rockefeller Institute – Milk Supply, 1901-1902, Series O-Rockefeller Boards, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller, Rockerfeller ArchiveCenter.

In addition to their survey of physical facilities, the investigators took samples of milk from different points along the supply chain, from farms to tenement homes. At each stage, they measured the bacterial content of the samples. Bacteria is present in all milk, but as milk ages the bacterial content rises rapidly. Because high temperatures increase the bacteria count, which in turn increases risk of disease, it was common for epidemics to emerge in the summer months, and for infant mortality to rise in the hot weather.

What the Milk Inspectors Found in the Milk

The investigators had determined that the safest milk would have a bacterial content of 10,000 to 100,000 organisms per teaspoon. And yet, they found that some samples contained as many as 4 million to 600 million bacteria per teaspoon. These samples most often came from the grocery stores within tenement districts. This bacteria count, coupled with the unsanitary grime picked up in many facilities, led to bacterial diseases such as typhoid fever and diphtheria.“The Milk Supply of New York, Some of the Facts Brought Out by the Investigation of the Rockefeller Institute”, Rockefeller Institute – Milk Supply, 1901-1902, Series O-Rockefeller Boards, Office of the Mssrs. Rockefeller, Rockefeller Archive Center.

From Farm to Tenement: the Milk Supply and Infant Mortality

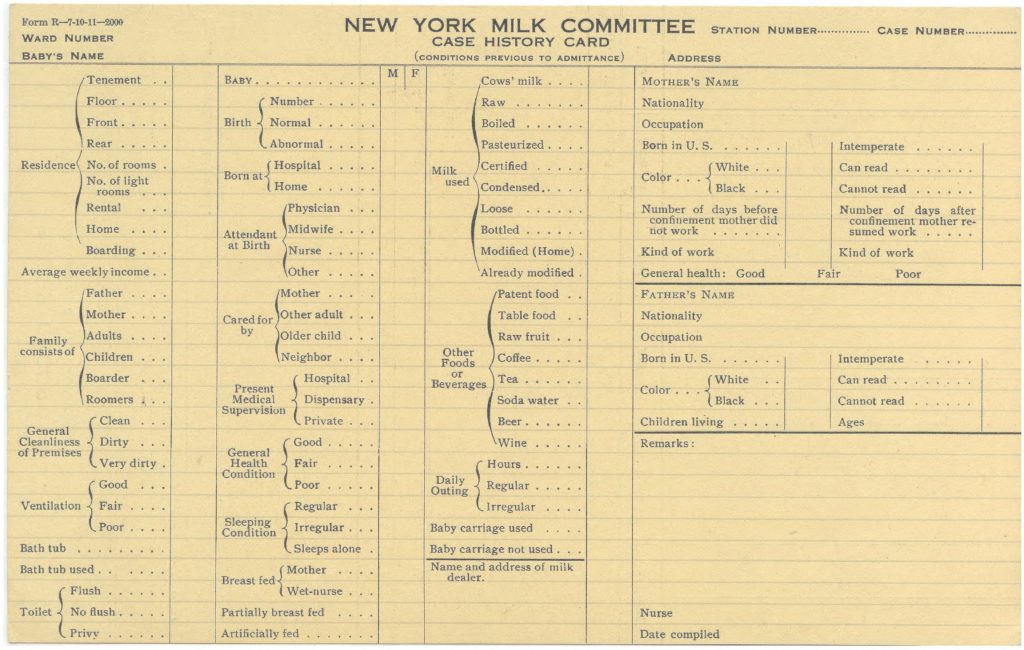

Finally, the survey team studied infants who were fed by the milk delivered by the farms and creameries.

Investigators selected three groups of infants from different areas of the city, all of whom were being fed solely on cow’s milk. In each geographic area, the investigators split the group of infants into two sub-groups. One group of families continued to purchase milk from the local grocery as they normally would. Meanwhile, the other was given milk from select companies that investigators had deemed of good quality. That way, the investigators could control for both residential location and milk consumed.

The scientists found that the children who ingested the approved-quality milk had fewer instances of serious illness. Those who drank milk from neighborhood groceries fared much worse. They suffered numerous cases of serious illness, and many died. The investigators concluded that the combined issues of sanitation throughout the milk production chain had a dramatic effect on the health of the city’s children, contributing to infant mortality rates.

Hygiene and Cleanliness to Fight Infant Mortality

Despite the dire conditions in many tenement districts, milk safety improvement was possible. The survey found that, for most facilities, changes need not be dramatic in order to be effective. Minor improvements in staff hygiene and in facility and animal cleanliness could result in large improvements in milk quality.

In fact, one of the most important findings of the milk study was the need to train farm and creamery staff in basic milk purification and sterilization methods. In some instances, this was as elemental as explaining to staff that, even if the milk did not smell bad or look dirty, it could still be unsafe to drink. The investigators also studied the amount of bacteria in milk kept on ice compared to room temperature and recommended keeping the milk as cold as possible.

Rallying Public Opinion Around Clean Milk

While the survey’s results were of obvious public interest, and the changes needed were feasible, the project faced a major challenge. The investigators had no legal authority to enforce changes to any of the sites of production, transportation, or distribution they examined. Recommendations were only suggestions, not mandates.

The survey investigators realized that public opinion might spur new legislation. This would be the key to long-term enforcement and public health benefits. Therefore, the team released the results of its survey to the public not long after presenting it at the Institute’s board meeting. With headlines such as “Germs Swarming in City’s Purest Milk” and “New York’s Milk Supply… Many Dairies Found to be in a Filthy Condition…,” the public rallied to urge action by the survey committee and the New York City Department of Health. The connection of tainted milk to infant mortality was especially alarming and easily provoked a public response.News Clippings – Rockefeller Institute Milk Dairies Investigation, circa 1902, RG 365, Office of Public Affairs- News Clippings, Rockefeller University Records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Germs Swarming in City’s Purest Milk

1902 Headline

From Public Opinion to Public Policy

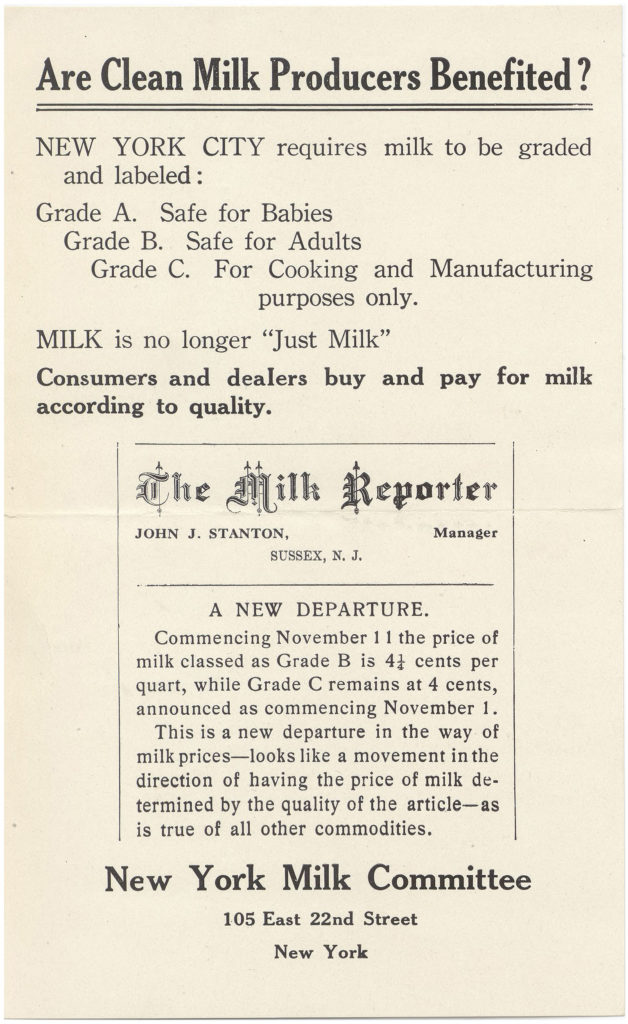

The public awareness approach worked. In response to public outcry, the City of New York created and funded four new positions — inspectors who would carry out the Health Department’s new milk certification program.

The new inspectors would now have authority from the State’s Health Department to visit farms, transportation centers, and groceries. They could now inspect the conditions and force businesses to make changes under penalty of a fine.

Going National: the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906

A copy of the New York City milk study report was sent to the US Department of Agriculture, which at the time was investigating the nation’s milk supply. The New York report helped inform the legislation which became the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

Following the milk survey report, the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research ceased its funding of milk investigations. With New York City investigators on the job and a federal food safety act on the books, the Institute felt that its work could move on to other related areas of public health and medicine to begin to tackle such diseases such as polio and yellow fever.

Medical Research for the Public Good

The milk survey embodied the Rockefeller Institute’s original goal of applying scientific study to solve public health problems. However, as time went on, the Institute moved away from this field. Instead, it sharpened its focus solely on scientific research. Meanwhile, the Rockefeller Foundation took up the mantle of public health after its formation in 1913.

For their part, Rockefeller Institute staff and leaders hoped that their fundamental medical research would in time serve in a practical role to the public. Over a century since the milk study, the institution now called Rockefeller University has developed countless products of public benefit, including a vaccine for meningitis and the AIDS cocktail therapy.

The milk survey achieved the goals set out for it. It changed the conversation about New York’s milk supply and helped shape how scientific methods could assist in public health improvement. Additionally, the milk survey was a public relations success for the Institute. It also helped reinforce the Institute’s value in the mind of John D. Rockefeller, who would fund the Institute to the tune of $65 million by 1928.E. Richard Brown, Rockefeller Medicine Men (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979) 105.

Research This in the Archives

- “New York Milk Committee,” 1919, Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Appropriations – Public Health, Subseries 3 01, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “New York Milk Committee,” 1914-1915, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Research Group 1, Sub-Group 1.1, Series 100-257, International and United States, New York, Series 235, New York – General (No Program), Subseries 235.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Rockefeller Institute – Milk Supply,” 1901-1902, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Institute, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Public Health: Food, Water, Milk,” 1911-1931, Rockefeller Foundation records, Pamphlet File, Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.