A Letter Challenging the Status Quo

In early 1957, Ford Foundation Behavioral Sciences director Bernard Berelson reached out to renowned anthropologist Margaret Mead for her advice on a short list of potential fellowship recipients. Mead, the curator of ethnology at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, had herself received support from Ford the previous year, and it was (and remains) common practice among foundation staff to ask disciplinary experts for such recommendations. Berelson was also a leading behavioral scientist who had run the Ford program since 1951. A specialist in mass media and communication, Berelson was not an anthropologist but was knowledgeable enough to draft a rough list of promising social scientists. He encouraged Mead to critique his list of what he called “great men” in anthropology.

Mead responded by figuratively tearing Berelson’s list apart, candidly criticizing the “orthodoxy” of his selections. In an April 1957 letter preserved in the Ford Foundation archival collections, Mead argued against the idea that the best scholars necessarily hailed from top universities. Moreover, she questioned whether established scholars merited further investment by a foundation that supposedly sought to push a field forward. Furthermore, although she did not make an overtly feminist critique of the list of “best men” (as her objection was more about institutional affiliation than gender), when she wrote back to Berelson, Mead called her own list “able people.”“Grant in Aid program for the ‘best men’ in the behavioral sciences – Ford Foundation,” L57-350, 1957. Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Log Files (Grant and Project Proposals), 1957, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In fact, Margaret Mead’s entire life’s work challenged established ideas about culture, intelligence, and merit. She was the most famous anthropologist of her day and her books were popular best-sellers. She worked not from the proverbial ivory tower of a university, but in a public-facing position at a museum, and she was a leader in the applied anthropology movement — anthropology done in the context of government agencies, museums, health care and social services organizations, and the like.

Although this exchange with Berelson was a minor episode in a long and distinguished career, the story of Margaret Mead and Ford Foundation philanthropy offers a glimpse into Mead’s worldview. It also reveals the challenges of funding a field in flux, and how the grant selection process and a foundation’s internal power structures may just as easily inhibit new ideas and prevent innovations from flourishing as encourage them.

Dismantling Scientific Racism

First, it’s important to take a look at the ideas behind the story. Anthropologist Margaret Mead is known today for pioneering the concept of cultural relativism, a counter-argument to scientific racism and Western white supremacy.

Beginning in the 1930s, through her early ethnographic fieldwork in Samoa, Papua New Guinea, and Bali, Mead challenged the prevailing notion in the West that the people she studied were culturally inferior, even “savages.” Mead would go on to challenge other cultural constructs, including gender. A decade before Alfred Kinsey‘s paradigm-changing reports were published, Mead argued that human sexuality is fluid.

One of the revolutionary aspects of Mead’s work is that she turned her critique toward American society itself — even challenging the institutions and structures that supported her research. This is evidenced in that 1957 interaction with the Ford Foundation’s Bernard Berelson.

Cultures are Relative

Mead conducted her early ethnographic fieldwork during the 1920s and 1930s among the peoples of Ta’u in Samoa and the Manus in Admiralty Islands. From this fieldwork, she went on to dedicate her career to combatting the pervasive acceptance of scientific racism. The discourse of the time often characterized those she studied as biologically and culturally inferior “savages” in comparison to Western societies. But Mead implored her readers to view all aspects of life as both relative and subjective in their value.

To dismantle the ethnocentrism and racism of scholarly and popular discourse on non-Western peoples, Mead researched the effects that culture had on shaping the behavior of adolescents. She noticed a discrepancy between American perceptions of adolescents and that of her ethnographic subjects toward their society’s teenagers. In the US, behaviorists particularly saw the period of female adolescence as a tense time fraught with universal “difficulties,” whereas the adolescent period among those Mead studied in the South Pacific was not plagued with such “difficulties,” and in fact was experienced as a period that child and adult alike embraced.

Nature vs. Nurture

Noticing this, Mead posed a profound research question: “Are the disturbances which vex our adolescents due to the nature of adolescence itself or to the civilization?”Margaret Mead, and Franz Boas. 1929. Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilisation.With this question, Mead called on Americans to examine their own assumptions, introducing the idea that nurture has profound effects on culture formation.

This question, sometimes dubbed the nature vs. nurture debate, became central to all of Mead’s work, not only in Coming of Age in Samoa but in her subsequent studies of Bali and the Admiralty Islands as well. Mead focused on this question in the context of culture change over many generations, showing how, for example, the increasing influence of “outsider” cultures began to shape the adolescent experience (and culture at large) in significant ways in these once-isolated locales.

“Are the disturbances which vex our adolescents due to the nature of adolescence itself or to the civilization?”

Margaret Mead, 1929

The Ford Foundation: Establishment Funder

The Ford Foundation funded Margaret Mead’s work in Bali in the 1950s. At that time, Ford was the largest foundation in the world, and the first to acquire a $1 billion endowment. In 1949, Ford leadership had identified the foundation’s primary goal as fostering international peace and understanding through the “understanding of man.” The grant supporting Mead’s work fit into Ford’s Behavioral Sciences Program, a program that ran from 1951 to 1957. Ford staff hoped work like Mead’s would encourage intercultural understanding and stave off future social problems.

While at first glance, Bernard Berelson might seem to represent the mid-century establishment, in fact, he found himself frequently at odds with the Ford Foundation Board of Trustees. Those establishment men, representatives of American industry and the ivory tower, viewed the Behavioral Sciences Program as too soft and unscientific at best; at worst, controversial and the most high-risk of Ford activities.

For instance, Berelson and his staff organized a conference on school desegregation but were unsuccessful in creating a program from it that could pass muster with the Trustees. He proposed funding research on Indigenous peoples and on race in the US South — all ideas deemed too controversial, further alienating Berelson and his program. For years, the Behavioral Sciences Program survived because Ford President H. Rowan Gaither supported and protected it.Bernard Berelson, Oral History, July 7, 1972. Ford Foundation records, Special Collections, Oral Histories, Oral History Projects, Series IV, Access Copies, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Nevertheless, in Margaret Mead’s eyes, Berelson’s funding approach seemed too “orthodox.”

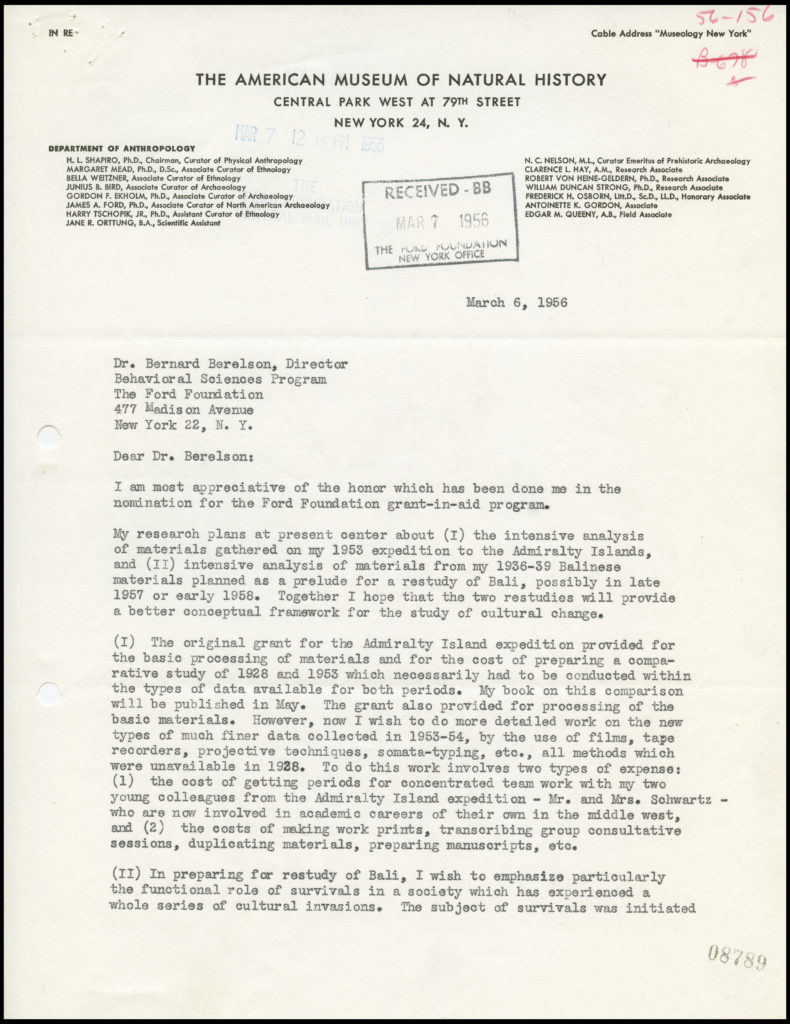

Margaret Mead’s 1956 Ford Foundation Grant

As assistant curator at the American Museum of Natural History, beginning in 1926, then rising to curator of ethnology, a position she held until her death in 1978, Margaret Mead expanded her research findings with the help of a grant-in-aid from the Ford Foundation. Writing to Bernard Berelson, on March 6th, 1956, Mead expressed gratitude for her nomination for the Ford Foundation fellowship program.Mead Margaret to Bernard Berelson, March 6, 1956, “Me-Mi – Individuals,” Signature Letters from Individuals, Ford Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Mead planned to use the grant to help cover the expenses of her research team as well as “the costs of making work prints, transcribing group consultative sessions, duplicating materials, preparing manuscripts.”

The Ford support allowed Mead to finish writing and to publish New Lives for Old: Cultural Transformation: Manus, 1928-1953. This monumental work studied the rapid cultural change of the Manu people, including their adoption of many “American” attitudes during the course of the US occupation of the Admiralty Islands in World War II.

It’s Nurture, Not Nature

Mead noted that Manus adolescents who grew up during the American occupation “were transformed into sulky, inwardly rebellious, but outwardly conforming young adults” engulfed by “the competitiveness of American life”.Mead, Margaret. 1956. New lives for old: cultural transformation : Manus, 1928-1953. London: Gollancz.The Americanized post-war environment transformed Manus views of the adolescent period, from celebration to disdain. Because the variable in this study was context rather than biology (she was studying the same people over time), Mead gathered evidence that led her to conclude that culture was the primary factor in affecting human behavior, perceptions, and ideas.

Cultural Determinism and America’s Racism

In a segregated United States, the Ford Foundation’s funding of Mead’s work could not have been more timely. Mead introduced the broader American public to cultural determinism, the idea that environment shapes our behavior. This was more or less the nurture over nature argument Margaret Mead had been making since the 1930s. Mead’s work challenged racist ideas that permeated even scholarly “scientific” works circulating in the United States at midcentury.

Mead demonstrated great cunning in how she mobilized her findings on the Balinese “cultural survivals” that occurred with the modernization campaigns of the Indonesian State. Her reframing of the “survivals” concept went against both racist and colonialist discourses. Whereas previous scholars had viewed cultural survivals as vestiges from a civilization’s past stages of “savagery” and “barbarism,” literally seeing them as backward-facing remnants, Mead proposed that these cultural traits remained because they served a functional purpose in the modern context.

I wish to emphasize particularly the functional role of survivals in a society which has experienced a whole series of cultural invasions.

Margaret Mead, 1956Mead Margaret to Bernard Berelson, March 6, 1956, “Me-Mi – Individuals,” Signature Letters from Individuals, Ford Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Margaret Mead effectively subverted the older paradigm of Western culture as the liberating “civilizing” power. In fact, this culture could be detrimental and destructive.

The Detriment of “Modernization” to Balinese Culture

The Ford grant also allowed Mead to reexamine the ethnographic work she had conducted in Bali. She wrote to Berelson that her evidence demonstrated “purposive change” from the “rapid modernization movement, as part of the new Indonesian state.”Mead Margaret to Bernard Berelson, March 6, 1956, “Me-Mi – Individuals,” Signature Letters from Individuals, Ford Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

This change differed from the culture change Mead had witnessed in the Admiralty Islands. In Bali, Mead observed that certain elements of “traditional” Balinese culture lived on as cultural “survivals” of the past in this turbulent period in Balinese Indonesian history.

Margaret Mead challenged both the prevailing opinions in the nature versus nurture debate, and within her own field of anthropology. By extension, Mead’s critique also challenged the development ideology that her own funder, the Ford Foundation, had adopted at that time.For a developed analysis of mid-century development ideology written by a longtime Ford Foundation staffer, see Francis X. Sutton, “Development Ideology: Its Emergence and Decline,” Daedalus Vol. 118, No. 1, “A World to Make: Development in Perspective” (Winter 1989), pp.25-60.In short, her work ran counter to the idea that promoting Western political and economic structures around the world would be objectively beneficial to non-Western cultures.

A Continued Relationship with the Ford Foundation

In the years following Margaret Mead’s Ford grant, she would become a trusted advisor to Bernard Berelson on many projects. When she responded to his calls for advice, it seems Mead never worried about alienating Berelson by disagreeing with him and was forthright in expressing her opinions.

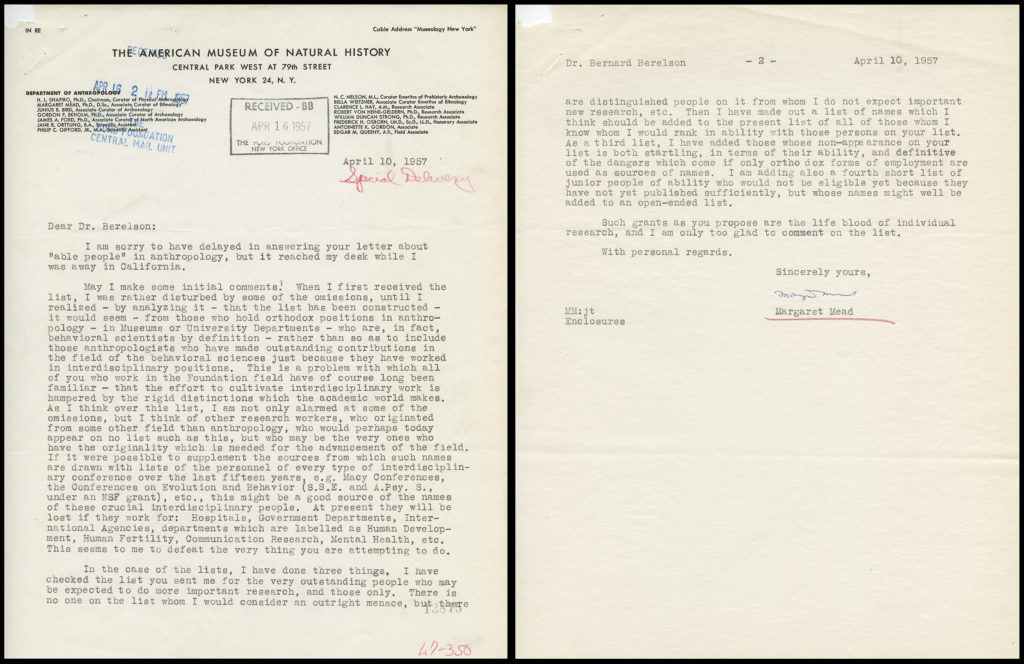

In that April 10, 1957 letter, Berelson had asked that Mead comment on his list of “best men” in anthropology. Mead was frank and candid, pointing out Berelson’s conservative approach to identifying talented or promising researchers. She wrote,

I am not only alarmed at some of the omissions, but I think other research workers, who originated from some other field than anthropology, who perhaps today appear on no list such as this, but who may be the very ones who have the originality which is needed for the advancement of the field.Margaret Mead to Bernard Berelson, April 10, 1957, “Me-Mi – Individuals,” Signature Letters from Individuals, Ford Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Margaret Mead, 1957

Challenging Established Criteria, Arguing for Innovative Grantmaking

Revolutionary for her time, Margaret Mead understood the dangers that come with academic complacency. To be sure, Berelson had his own struggles with what he called a “conservative” Ford Foundation Board of Trustees. As noted above, the Board was repeatedly unwilling to take a risk on a program already on the margins. What Mead saw as orthodoxy, Berelson would later argue was simply putting limited funds to their best use. “We were out after knowledge and knowledgeable people” he would later recall.Bernard Berelson, Oral History, July 7, 1972, p.73. Ford Foundation records, Special Collections, Oral History Project, Transcripts, Series IV, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Margaret Mead critiqued a field intent on staying closed off from outside ideas and non-traditional scholars. In doing so, she not only defied the state of anthropology in her time, but the rigid confines of traditional disciplinary thinking and philanthropic strategy.

We were out after knowledge and knowledgable people.

Bernard Berelson, 1972Bernard Berelson, Oral History, July 7, 1972, p.73. Ford Foundation records, Special Collections, Oral History Project, Transcripts, Series IV, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Mead did her graduate work under Franz Boas at Columbia University, where Boas built the first anthropology program in the country and trained the first generation of US anthropologists. His graduate students went on to establish the discipline in the American context, spreading the fundamental Boasian concept that all cultures are equal and must be understood on their own terms. Among his students were several distinctive women, from Ruth Benedict, who served as his teaching assistant and a special mentor to Mead, to renowned Black folklorist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston.Frank Salamone, “His Eyes Were Watching Her: Papa Franz Boas, Zora Neale Hurston, and Anthropology” Anthropos 109:1 (2014) 217-224. Mead, Benedict, and Hurston were among the few pioneering women in anthropology, a male-dominated field at that time.

The Dangers of Orthodoxy in Philanthropic Giving

Sometimes it’s best to just start from the blank page. While editing Berelson’s list, Mead decided to start over and create two alternative lists of names. As she put it, while no one on Berelson’s list could be considered “an outright menace,” neither did she expect from them any pathbreaking research in the future. One of Mead’s new lists consisted of individuals “whose non-appearance on your (Berelson’s) list is both startling, in terms of their ability, and definitive of the dangers which come if only orthodox forms of employment are used as sources of names.” In the main, Mead felt that Berelson’s list was comprised of usual suspects, reflecting a rigidity and resistance to interdisciplinarity,

Your list is […] definitive of the dangers which come if only orthodox forms of employment are used as sources of names.

Margaret Mead, 1957Margaret Mead to Bernard Berelson, April 10, 1957, “Me-Mi – Individuals,” Signature Letters from Individuals, Ford Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Mead also made a second list of names of “junior people of ability,” researchers who hadn’t yet published enough to be considered leaders in the field but whose work should be encouraged in future.

In this way, Mead pushed Berelson and the Ford Foundation to expand the boundaries of the field of anthropology and encourage cross-disciplinary approaches to understanding human culture.

The Margaret Mead Lists

The lists of proposed fellowship recipients Mead sent to the Ford Foundation reflects her commitment to crossing disciplinary and institutional boundaries. In fact, she titled one list “Names whose omission from the initial list points up the need for attention to interdisciplinary appointments.”Margaret Mead to Bernard Berelson, April 10, 1957, “Grant in Aid program for the ‘best men’ in the behavioral sciences – Ford Foundation,” L57-350, 1957. Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Log Files (Grant and Project Proposals), 1957, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Entries on these lists included anthropologists working in hospitals and non-university educational institutions, for example her former husband, Gregory Bateson, working at the time for the Veterans Administration. There were also emerging scholars, and people working in fields such as history, folklore, and psychology. Notable individuals included psychologist Erik Erikson, ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, and urbanist and sociologist William H. Whyte (who was also a Rockefeller associate).Margaret Mead to Bernard Berelson, April 10, 1957, “Grant in Aid program for the ‘best men’ in the behavioral sciences – Ford Foundation,” L57-350, 1957. Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Log Files (Grant and Project Proposals), 1957, Rockefeller Archive Center. The William H. Whyte papers are also preserved at the Rockefeller Archive Center and Whyte’s interactions with the Rockefeller family and philanthropies are documented in several other RAC collections. Despite Berelson’s tendency to refer to the proposed funding candidates as “best men” or leading men,” there were a couple of women on his initial list. Mead added a few more, including Dorothy Lee and British anthropologist Marian Smith, a curator at the Royal Anthropological Institute. One name on Mead’s list was closer to home – literally. Cultural anthropologist Rhoda Métraux, working at New York Hospital, was a close professional and personal partner of Mead’s. The two collaborated and lived together from 1955 until Mead’s death in 1978.

Margaret Mead described how highly she thought of people willing to try new scholarly and methodological approaches, including technology. She explained,

I expect important contributions from those anthropologists who are alive to the use of models from communication theory, and ethology, to the need for micro-analysis by the use of modern methods of recording, to the possibilities of pattern analysis using large numbers of variables suitable for computer treatment, to contemporary work on the brain […]

Margaret Mead, 1957Margaret Mead to Bernard Berelson, April 10, 1957, “Grant in Aid program for the ‘best men’ in the behavioral sciences – Ford Foundation,” L57-350, 1957. Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Log Files (Grant and Project Proposals), 1957, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Berelson Listened

Bernard Berelson took to heart Margaret Mead’s advice. In the end, his final list for the “leading men grants” included at least one woman, and a few researchers who used innovative and interdisciplinary methods. It turned out that some of Mead’s suggestions were already on Berelson’s radar, it was just that he had organized them by discipline. He wrote,

Let me assure you that we are particularly grateful for your additions to the list. Some of the names appeared on the lists covering other disciplines but some were new to us and we are glad to have them. As I am sure you will appreciate, it is always easier to handle such names within recognized disciplines and that makes us all the more grateful…“Grant in Aid program for the ‘best men’ in the behavioral sciences – Ford Foundation,” L57-350, 1957. Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Log Files (Grant and Project Proposals), 1957, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Bernard Berelson, 1957

All for Naught? The End of Ford’s Behavioral Sciences Program

Berelson envisioned large, multi-year fellowships to the most “able people” in order to provide ample time to build the field, but his vision was cut short. In the end, he was unable to act meaningfully on Mead’s recommendations because the Behavioral Sciences Program was to be no more.

In 1957, on the heels of the arrival of a new Foundation president, Henry Heald, the Behavioral Sciences Program came to an end. On why the Program was terminated, Berelson said in his later oral history:

I really don’t know and I don’t know whether anybody does. But certainly this kind of thing [the political concerns of the time] was closely involved in it. […] [S]ome well-placed people thought that when Heald came on board that, so to speak, this was his price of admission; he was told, ‘You get rid of the Behavioral Sciences Program, we don’t like that.’

Bernard Berelson, 1972Bernard Berelson, Oral History, July 7, 1972, pp.40-41. Ford Foundation records, Special Collections, Oral History Project, Transcripts, Series IV, Rockefeller Archive Center.

No Middle Ground for Berelson

At the close of his program, Berelson gave a large number of terminal grants to fund another few years of explorations in the behavioral sciences — in fact, the largest docket he ever had to work with in a year. But it was all to tie-off these activities, which the Trustees deemed too risky and which Margaret Mead deemed too orthodox.

Lasting Effects of Margaret Mead’s Ideas

Margaret Mead was a true maverick of her time. Helping to both popularize and open the doors of anthropology, Mead broke down disciplinary walls. She was also a polarizing figure–she was widely embraced by the American mainstream but critiqued from both the Right and the Left, while prompting mixed feelings among anthropologists themselves.

As anthropology’s most popular figure of the twentieth century, Margaret Mead turned the findings of her research onto her home country. Her critiques of even her own philanthropic funding source demonstrated her commitment to toppling existing paradigms. She hoped to give voice to the attitudes and experiences of other cultures that would otherwise have been little understood, and to support scholars who would have otherwise been overlooked. Perhaps it was her own privileged position as a cultural expert that afforded Margaret Mead the freedom to speak openly to powerful philanthropic funders.