For much of the mid-twentieth century, population and demography were scientific fields focused almost solely on concerns about resource constraints and overpopulation. Birth control technologies and reproductive science emerged as solutions to a numbers problem, not as tools for women’s empowerment. That framework changed decisively in the early 1990s, with one particular international conference marking a turning point towards women’s rights — or as one Ford Foundation staffer described it, a “women oriented view.”

The UN International Conference on Population and Development

In September 1994, more than 4,000 people gathered in Cairo, Egypt to participate in the United Nations International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD). Those present included representatives of government delegations and more than 1,700 foundations, NGOs, and other organizations. Some came for the conference itself, while others came to participate in the NGO meetings and events that ran concurrent to it.Margaret Hempel, “Reproductive Health and Rights: Origins of and Challenges to the ICPD Agenda,” Health Transition Review 6, no. 1 (April 1996), 77.

The lively conference was a critical turning point in shifting global policy from a longstanding focus on curbing rapid population growth to promoting women’s rights and reproductive health more broadly. The conference participants also underscored the importance of supporting and encouraging the leadership of women’s rights advocates in the Global South.

The ICPD was an important turning point for the Ford Foundation too, representing the culmination of the Foundation’s own changing approach to population and reproductive health. Beginning in the late 1980s, Ford began moving away from the family planning and demographic work that had defined its grantmaking in population fields since the 1950s and 60s. Ford program officers’ efforts in the lead-up to the ICPD helped enact this shift both in international discourse and within the Foundation itself.

Philanthropy and Population Before the ICPD

The Ford Foundation’s investment in the outcomes of the ICPD was built upon decades of engagement by other philanthropic actors in the field of population and family planning. In the 1910s and 1920s, for example, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. founded and contributed significant support to the Bureau of Social Hygiene, whose work included support for family planning, sex education, and sexual health programs. He also provided anonymous support to Margaret Sanger’s American Birth Control League to fund contraceptive research.

John D. Rockefeller 3rd followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming deeply interested in the field of population. After failing to convince his fellow trustees at the Rockefeller Foundation to contribute significant resources to the reproductive technologies aspects of the field (at the time, the Foundation instead supported demographic work, which it termed “human ecology“), he turned to forming and funding a new, independent organization, The Population Council. Incorporated in November 1952, The Population Council sought “to stimulate, encourage, promote, conduct and support significant activities in the broad field of population.”Population Council, Inc. – Bylaws and Certificate of Incorporation, 1952, John D. Rockefeller 3rd papers, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller Files, Series 1, Population Interests, Subseries 5.

Its major funding came from John D. Rockefeller 3rd, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and the Ford Foundation. Between 1954 and 1968, Ford Foundation grants made up more than forty percent of the Population Council’s budget.Oscar Harkavy, Lyle Saunders, and Anna L. Southam, “An Overview of the Ford Foundation’s Strategy for Population Work,” Demography 5, No. 2 (1968), 542.

By the 1960s, the Ford Foundation was heavily invested in population work. Foundation program officers described their approach in a 1968 article in the journal Demography:

We in the Foundation believe that the quality of life is threatened by excessive rates of population growth–that the problem of balancing the human population against an environment capable of supporting it with a rising standard of life is one of the great challenges to mankind. We believe, therefore, that a foundation concerned with human welfare must give high priority to helping nations reduce their fertility.”

“An Overview of Ford Foundation Strategy for Population Work,” 1968Oscar Harkavy, Lyle Saunders, and Anna L. Southam, “An Overview of the Ford Foundation’s Strategy for Population Work,” Demography 5, No. 2 (1968), p.541.

The vast majority of this grantmaking was focused on curbing population growth and promoting family planning in developing countries.

Towards a “Comprehensive, Women Oriented View”

Twenty years later, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Ford Foundation began to redefine its population program under President Franklin Thomas and Vice President Susan Berresford. In 1989, Ford hired Dr. José Barzelatto, former Director of the Human Reproduction Programme at the World Health Organization, to direct its Reproductive Health and Population program. Soon after he was hired, Barzelatto brought in Margaret Hempel as an assistant program officer.

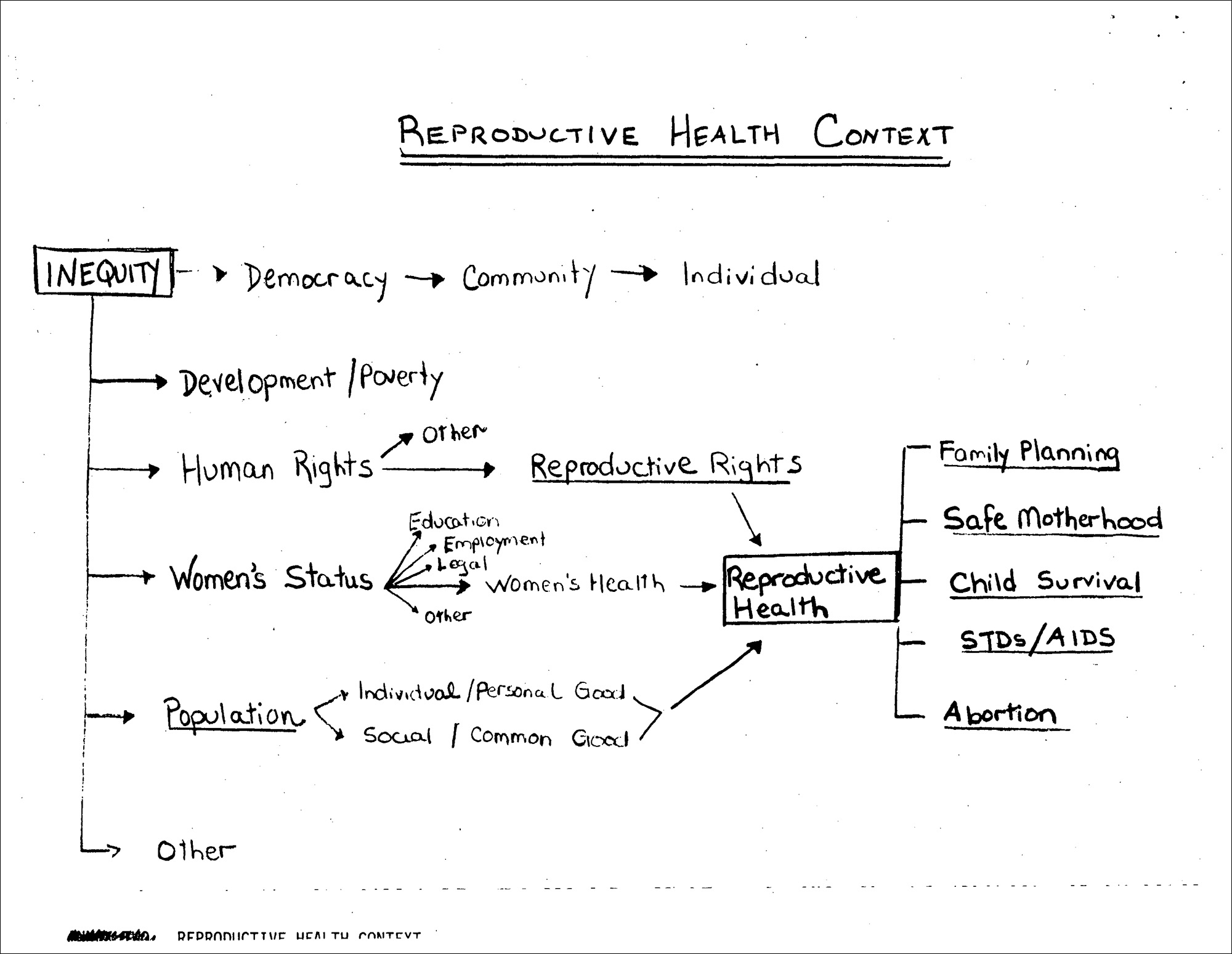

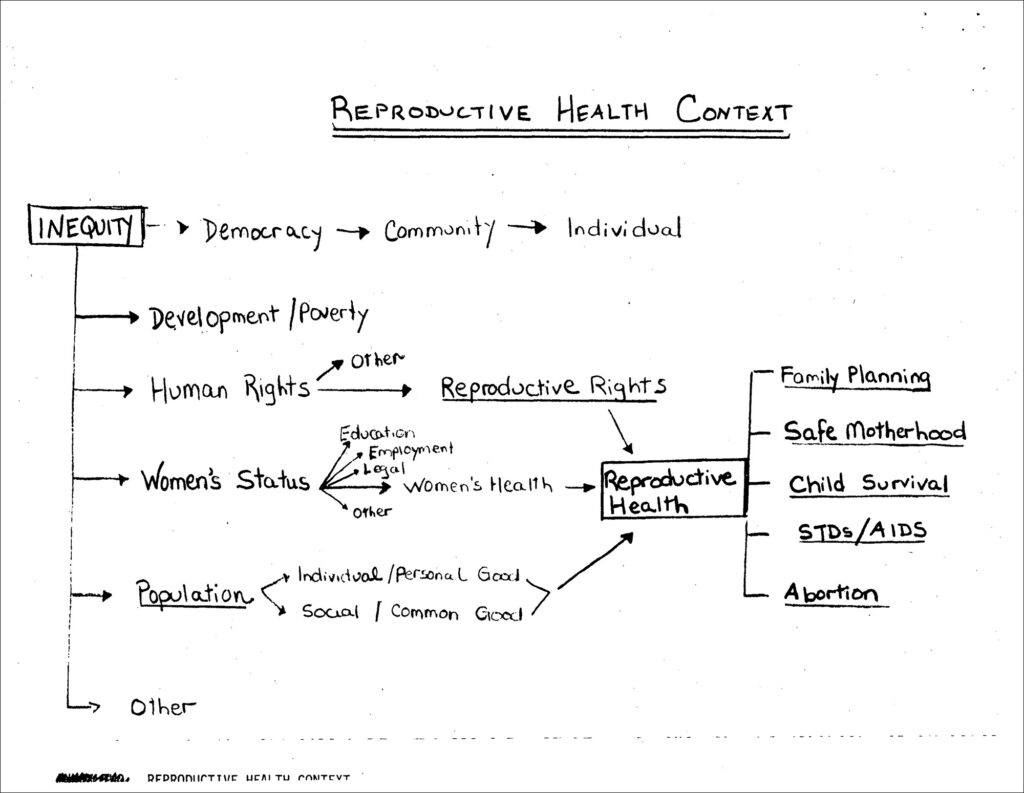

Barzelatto and Hempel transformed the Foundation’s international population work. They recognized that the field was evolving into a “more comprehensive, women oriented view of what could be termed ‘reproductive health’”.Meeting Notes, Reproductive Health and Population Program Officers Meeting, March 5-7, 1990 (Reports 015871), p. 1, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center. They summarized their approach in a 1991 program strategy paper entitled Reproductive Health: A Strategy for the 1990s.

[The new program] makes reproductive health its centerpiece, emphasizes social, cultural, and economic factors that influence reproductive health, and pays special attention to disadvantaged women of developing countries, in both rural and urban areas, throughout their reproductive life cycle.

Barzelatto and Hempel, 1991Ford Foundation, Reproductive Health: A Strategy for the 1990s (New York, NY: Ford Foundation, 1991), v. Also available in Ford Foundation records, Publications, Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Hempel and Barzelatto believed that the Ford Foundation was uniquely positioned to pursue this new strategy because of its “ability to work on sensitive issues that other donors may be unable or unwilling to fund.” Ford was willing to wade into controversial issues surrounding sexuality, fertility, and women’s rights, taking a broad social scientific approach when other foundations remained committed to less controversial work in demography and family planning.Ford Foundation, Reproductive Health: A Strategy for the 1990s (New York, NY: Ford Foundation, 1991), 23.

In practice, this shift dramatically reoriented the Foundation’s grantmaking. Ford previously emphasized grantmaking in population and demography, family planning in developing countries, reproductive sciences research, and contraceptive development.

The Foundation’s reimagined strategy took a much broader view of reproductive health and rights focused on three primary areas: supporting social scientific research and training about reproductive health; building or strengthening communications efforts around sexual, reproductive health and rights issues; and empowering women— and also men—to understand and take control their reproductive health needs. Ford also placed a high priority on global HIV/AIDS grantmaking, as well as grants focused on the sexuality and reproductive health of adolescents.“Reproductive Health and Population Program: A Progress Report, 1990-1992,” (Reports 012335), Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

… [a] more comprehensive, women oriented view of what could be termed “reproductive health.”

Program Officers Meeting, 1990Meeting Notes, Reproductive Health and Population Program Officers Meeting, March 5-7, 1990 (Reports 015871), p. 1, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Program officers in the Foundation’s global field offices were empowered to implement this strategy and tailor grantmaking in country-specific ways. In Eastern and Southern Africa in 1994, for example, this meant prioritizing grants that examined the power imbalance between men and women and how it affected sexual and reproductive health.

Grants to the University of Zimbabwe supported multidisciplinary studies of how gender roles impacted rates of sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancy, and the impact of those gender roles on individuals’ sexual and reproductive lives. “Sexuality and Reproductive Health; Reproductive Health and Population Program: A Progress Report,” (Report 015079), Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, 1994, p. 8.

In Kenya, grants supported a counseling intervention program for adolescent boys to address sexual violence, as well as grants to conduct community education efforts and provide support services for victims.

In Chile, Peru, and Colombia, program officers found that changing attitudes about women’s equality and the need for sex education enabled them to pursue work on sexuality and gender roles. Support for the Center for Research and Action in Public Health (CIASPO) in 1994, for example, focused on researching male gender roles and sexuality in Chile and implementing a pilot program aimed at educating men about gender equality in relationships and in family dynamics.“Sexuality and Reproductive Health; Reproductive Health and Population Program: A Progress Report,” (Report 015079), Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, 1994, p. 21.

Preparations for the International Conference on Population and Development

Ford’s Reproductive Health and Population program officers began planning for the 1994 ICPD conference well in advance of the meeting. In April 1993, they gathered in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The meeting offered program officers from Ford’s global field offices an opportunity to share their experiences and discuss issues of common concern related to their grantmaking. The agenda covered a broad range of topics, including ethics and reproductive health, sexuality, reproductive rights, HIV/AIDS, and abortion.

On the final day of the meeting, the program officers discussed the impending ICPD conference set for the following year. They reviewed efforts already underway, and strategized additional ways that they could help shape the conference’s outcomes.

Conference meeting notes give us a window into the conversation led by Margaret Hempel:

The International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) is an event that we are concerned with for a variety of reasons. First, the official document produced is used by governments to shape their own policies. The document and dialogue also impacts on the donor community. Further, the conference provides an opportunity to mobilize and form networks of NGOs. In the past, the documents have been written and revised without NGO participation. Our concern is to bring in voices of constituencies typically excluded from these processes and to promote collaboration between NGOs and governments. [emphasis added]

Ford Foundation Reproductive Health and Population Program Meeting, 1993“The Ford Foundation Reproductive Health and Population Program Meeting, April 27-30, 1993, Rio de Janiero, Brazil” (Reports 012898), p.36. Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Ford’s program officers understood the influence wielded by UN population conferences, which could directly shape national and global donor funding and policies. As a result, the work of convening the ICPD, including agenda drafting and even the conference’s official document, was done in the years and months leading up to the conference. By the time they gathered in Rio to preview the ICPD, the program officers’ preparations were already well underway.

In the following months, Ford’s program officers — both New York-based and in the foundation’s field offices — continued to support preparatory activities at the national and global level to ensure broad, diverse participation in the ICPD. Ford program officers also helped secure the participation of a range of women’s and reproductive rights groups in the meeting preparations and NGO activities surrounding the conference.“Reproductive Health and Population Program: A Progress Report” (Reports 015079), Sexuality and Reproductive Health report for discussion at the December 1994 meeting of the Board of Trustees, p. 28. Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

They supported several international women’s groups that ensured robust participation in regional meetings leading up to the ICPD, including the Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO), and Women’s Voices ‘94, a global NGO network that represented 15 countries and 23 organizations. Within these networks were several Ford grantees, including the International Women’s Health Coalition (IWHC), an international NGO based in the US, and Citizenship, Study, Research, Information and Action (CEPIA), from Brazil.

Building a Reproductive Health Field

In the lead-up to the Cairo meeting, Ford’s considerable reproductive health grantmaking was critical to shaping an international reproductive health and rights framework. Ford was not alone in this work; the MacArthur Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation also funded various ICPD activities. Ford’s grants, however, far exceeded those of its fellow foundations: Sociologist Perrin Liana Elkind calculated that Ford ICPD grants amounted to $5.5 million dollars, whereas MacArthur spent $1.5 million and the Rockefeller Foundation $1.8 million.

Ford’s goals for the ICPD were in line with MacArthur’s, and the two foundations coordinated their efforts to build a reproductive health agenda. Rockefeller had moved on from its earlier support for demographic work and had initiated its own Population Sciences program in 1982, focused on fertility and contraceptive research, directed by Sheldon J. Segal. Although sometimes working at cross-purposes, collectively the three foundations helped build a new reproductive health field through their support for a broad range of activities, including policy, communications, conferences, meetings, as well as specific ICPD planning and networking events.Perrin Liana Elkind, “How Foundations’ Field-Building Helped the Reproductive Health Movement Change the International Population and Development Paradigm,” (PhD diss., University of California Berkeley, 2015), 138-141.

Outcomes of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development

In a 1996 article reflecting on the origins and challenges to the ICPD, Margaret Hempel emphasized that the two previous United Nations international conferences on population, in Bucharest (1974) and Mexico City (1984), arose in response to concerns about the impact of dramatic population growth in the developing world. The outcomes of those conferences therefore reinforced an international emphasis on contraceptive use and family planning in developing countries.

Unsurprisingly, these conferences were, in Hempel’s words, “largely the domain of male government delegations, with input from a few key demographers and population organizations.” The same could be said of the Ford Foundation’s approach to population work before Hempel and Barzelatto dramatically reoriented the program in the 1990s.Margaret Hempel, “Reproductive Health and Rights: Origins of and Challenges to the ICPD Agenda,” Health Transition Review 6, no. 1 (April 1996), 77.

In stark contrast to the earlier meetings, the 1994 ICPD was shaped by a broad and diverse coalition of voices, and especially by voices from women in the Global South.

That distinction was evident in the ICPD’s resulting Programme of Action, approved by 179 national governments represented at the Cairo meeting.

The document is remarkable for its clear articulation of a new reproductive health framework: there is an overt emphasis on human dignity (Principle 1); advancing gender equality, protecting the right to control fertility, and eliminating violence against women (Principle 4); ensuring broad access to health care services including reproductive health care (Principle 8); and prioritizing the needs of youth and adolescents (Principle 11).

Ford’s program officers were thrilled to see that the ICPD document reflected the results of their robust grantmaking efforts. They also saw it as reflecting an important shift within their own institution. A December 1994 progress report noted that “[t]his shift at the global level mirrors the 1990 reorientation of the Ford Foundation’s Population Program to a Reproductive Health and Population Program.” This, of course, was no accident — it was exactly what Ford Foundation leadership had hoped and planned for in the years leading up to the Cairo conference.

Further Reading

Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports are created by recipients of research travel stipends and by many others who have conducted research at the RAC.

- Ogechukwu Ezekwem, “From Population Control to Reproductive Health Campaigns? Family Planning in Nigeria.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2017.

- Daksha Parmar, “Population Control, Foundations and Development of Demographic Research Centres in Maharashtra (India): 1950-1970.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2015.

- Ramona Braun, “Agents of Fertility: The Ford Foundation’s Fertility Research Program Guided by its Biomedical Advisors.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2013.

- Edmund Ramsden, “Negotiating the Problems of Population: Demography, Ecology, and Family Planning in the Post-war United States.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2010.