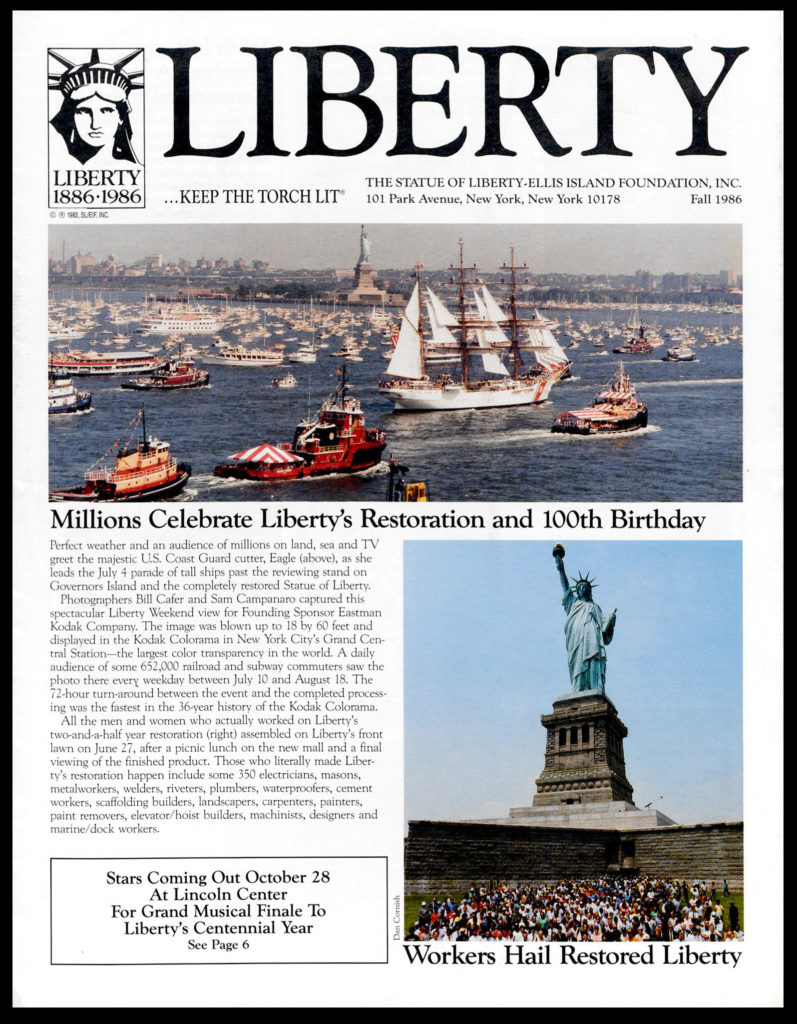

On July 3, 1986, New York City kicked off “Liberty Weekend,” a public festival celebrating the one-hundredth anniversary of the Statue of Liberty. The event was a true spectacle. Over six million people were treated to a massive fireworks show and a tall ship parade. There was a free concert by the New York Philharmonic. Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren E. Burger administered a swearing-in ceremony for 1,500 new immigrants who became American citizens that night. Furthermore, a newly refurbished Statue of Liberty was unveiled. President Ronald Reagan led the statue’s torch relighting ceremony. With dramatic flair, Reagan arrived on board a recommissioned World War II battleship.Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation Report, Rockefeller Family and Associates, General Files, 1987-1991, RG 39. David Rockefeller papers, Rockefeller Archive Center. Bernard Weinraub, “For Ronald Reagan, the Ceremonies Stir Pride and Patriotism,” The New York Times, July 5, 1986.

Underneath it all, the star-studded gathering represented more than just a patriotic celebration. This huge event was not merely a one-time occasion. It was part of a larger fundraising campaign to restore the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, two of the nation’s most important cultural sites. Both the event and the campaign showed the power of philanthropic giving to connect people to a cause. And in this case, widespread giving from the wealthy and from ordinary people helped express a nation’s connection to its cultural heritage.

Big Donors Create a Big Show

Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to suggest that “Liberty Weekend” would have been impossible without philanthropy. Roughly 700 major contributors donated to the fundraising campaign, including prominent businesses, philanthropists, and entrepreneurs. David and Laurance Rockefeller contributed — and hosted President Reagan at the Rockefeller family estate in Pocantico Hills in the northern suburbs during his weekend trip to New York.

Additionally, the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (DMLA), a nonprofit David Rockefeller founded in 1958, had played a part in the National Park Service (NPS) committee charged with developing and assessing restoration plans for the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island in the late 1970s. Moreover, large donations were made by such recognizable names as George Steinbrenner, the Coca-Cola Company, American Airlines, Time, Inc., and the Kellogg Corporation. The campaign was coordinated by the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation (SOLEIF) that President Reagan created in 1982. For a full list of contributors, see LIBERTY magazine, Fall 1986, Henry Luce Foundation records, RG 3, Rockefeller Archive Center. For a list of early sponsors, see “The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. List of Contributors as of May 12, 1983,” Ford Foundation records, Urban Poverty Program, Director, Office Files of Bernard McDonald, Series 2, Rockefeller Archive Center. For the DMLA role, see the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

On top of those already named, roughly 130 foundations also donated to the cause. Over $2.5 million came from the Kresge, Hearst, Vincent Astor, and Hewlett Foundations. The Ford Foundation gave $500,000 toco support the development of a new immigration museum at Ellis Island, and the Culpeper Foundation provided $150,000 towards the museum’s accessibility projects. Other significant contributors donating in excess of $100,000 included the Starr Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, and the New York Life Foundation. LIBERTY magazine, Fall 1986. “Grant Report – the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc.,” Charles E. Culpeper Foundation, Inc. records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The People Donate Too

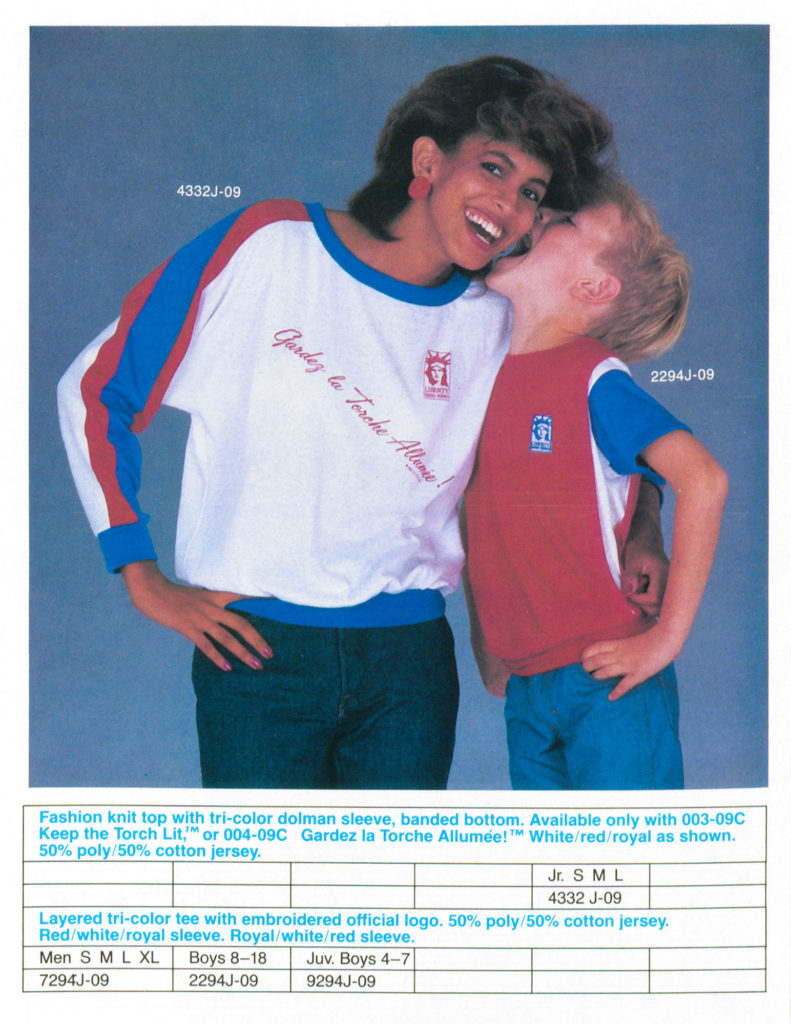

In addition to these high-profile donations, countless small donations collectively brought in millions. A particularly popular fundraiser was the specially made Statue of Liberty apparel, as well as other commemorative items for sale throughout the centennial year.LIBERTY magazine, Fall 1986.

All told, the campaign was an astounding success. By early 1987, it collected over $305 million. “Uses of $305.4 Million Raised to Date for Liberty Centennial Restoration Program (March, 1987)“, Rockefeller Family and Associates, General Files, RG39. David Rockefeller papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Monumental Task of Saving Monuments

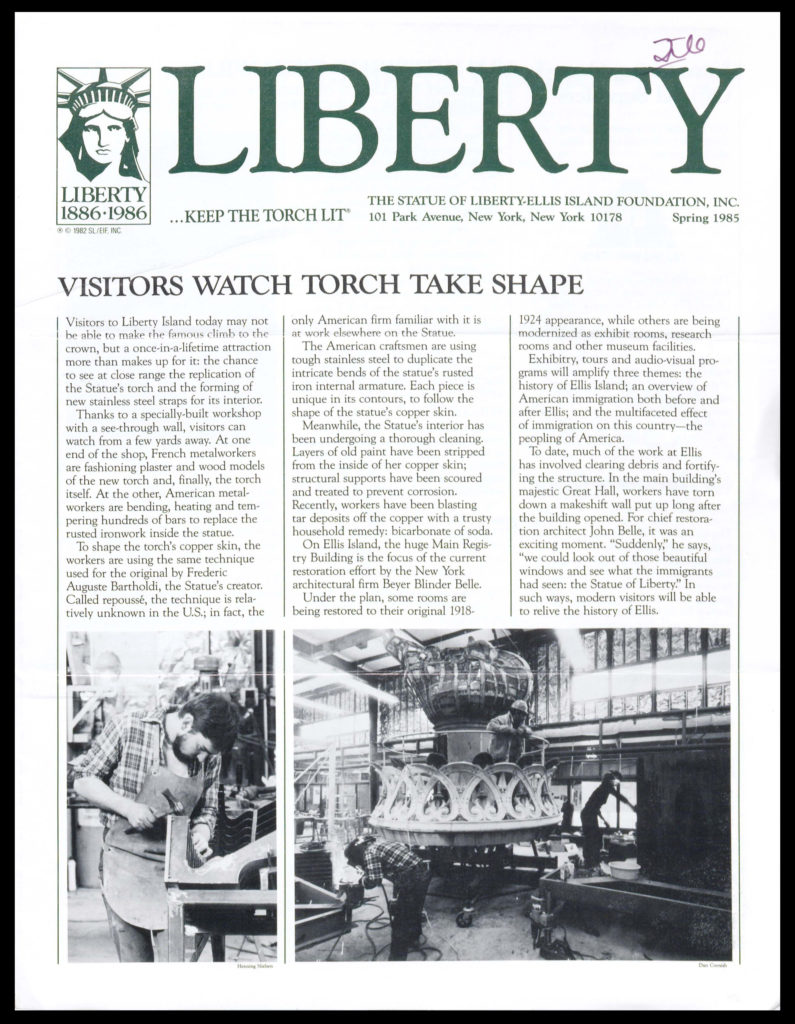

But even with plenty of funding, the actual work of restoring the Statue of Liberty proved to be no easy task. For one thing, the bars supporting its 200,000 pound exterior were deteriorating. Also, pieces of its right arm needed to be replaced. On top of all that, small bits of the torch had fallen into New York Harbor.Thomas Fleming, “Save the Statue of Liberty!” Reader’s Digest, July 1983, DMLA records, Series 2.3, RAC.

To raise even more public awareness, SOLEIF came up with a symbolic gesture. Since the statue had been a gift from France to the US in 1886, it hired a French architect to re-emboss the torch at an open-air workshop on Liberty Island. Then it sent the retired torch to lead the Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena, California.

In addition, there were other grand gestures. First, a new hydraulic elevator was installed in the statue’s pedestal — the tallest in North America to that date. Second, the entire year of restoration work was billed as a “Centennial Countdown.” The spikes in Liberty’s crown were replaced. Finally, perhaps the most painstaking task was replacing the roughly 1,700 iron support beams inside the statue one-by-one.“Liberty’s New Torch Will Be Built By French Artisans on Liberty Island,” “100 Year Old Torch of Statue of Liberty Will Lead Rose Parade on New Year’s Day,” and “Restoration Work on Schedule As Statue of Liberty Enters ‘Centennial Countdown Year,‘” DMLA records, Series 2.3, Rockefeller Archive Center.

A Museum of Immigrants

The Ellis Island restoration was even more lengthy and expensive. One report compared it to the “restorations done on the Palace of Versailles outside Paris.” Famously, American philanthropy played a major role in that, too. In fact, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (father of David and Laurance) donated $2.2 million to the restoration of Versailles in the early 1920s. In 2019 dollars, his support would be worth roughly $33.3 million.

SOLEIF planned to use over half of its projected budget to refurbish the island’s main building. There, a new museum would become the central attraction. Visitors would learn about immigrating through Ellis Island by experiencing some of what that process felt like. It would be one of the nation’s first cultural institutions “dedicated to the promotion, advancement, and understanding of America as a nation of immigrants.” The island opened to the public as the Ellis Island Immigration Museum in 1990, six years after restoration work began. Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation Report, Rockefeller Family and Associates, General Files, 1987-1991, RG 39. David Rockefeller papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

However, not everyone was optimistic about the new museum’s viability. When SOLEIF asked the Henry Luce Foundation to donate, Foundation president Henry Luce III replied with this question: “Who wants to go to Ellis Island…when it’s easier to get to Brooklyn?”William F. May to Henry Luce III, October 26, 1987, Henry Luce Foundation records, RG 3, Accession 2017:059, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Ultimately, the Foundation did make a modest grant of $10,000 toward the new museum. But Luce’s comments have turned out to be prophetic. The ease of travel to and from Ellis Island — or lack of ease — is still a topic of discussion today.

Luce’s hesitations aside, American philanthropy’s engaged support for the restoration and preservation of Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty breathed new life and relevance into both of these sites. The success of the 1980s campaign shows in the millions of visitors and tourists who visit these sites each year.