In honor of Women’s History Month, we have selected thirteen individuals from our collections to show the range of contributions women have made in the field of philanthropy. Some were or are powerhouse leaders in their fields, funded by foundation grants. Others work(ed) behind the scenes as philanthropy professionals. Still others have created philanthropic funds themselves.

While by no means exhaustive, these selected profiles demonstrate the import of women’s time, talent, and treasure across fields and eras, and help to illustrate how women, in diverse roles, have used philanthropy to build the world we live in today. And speaking of today, we’ve decided to present their philanthropic work in reverse chronological order.

Gay McDougall

Gay Johnson McDougall (pictured at left, above), an American lawyer, has dedicated her career to promoting human rights around the world. Among her many accomplishments, McDougall led the Southern African Project of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law from 1980 until the end of apartheid in 1994. With financial support from the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations and Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Southern African Project provided legal defense for political prisoners and documented violence and abuses against anti-apartheid advocates.“Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Southern Africa Project” Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, Projects (Grants); and “Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, 1980-1991,” Ford Foundation records, Programs, Human Rights and Governance Program, Office Files of Shepard Forman; “Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law: Apartheid Conference, 1981, 1985,” Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), International Relations, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Susan Berresford

Susan Berresford served as Ford Foundation president from 1996 to 2007, and today she continues to be a leader in the philanthropic field. She began as a staffer in the 1970s and was one of a handful of Ford Foundation women who advocated for equal pay, maternity benefits, and diversity-conscious hiring policies. Berresford’s internal advocacy eventually prompted change for women working within foundations and throughout the not-for-profit sector.

Mariam Chamberlain

The birth and development of women’s studies owes much to Dr. Mariam Chamberlain (1918-2013; pictured at right, above). She served as the Ford Foundation’s director of higher education from 1967 to 1981. The daughter of Armenian immigrants, Dr. Chamberlain earned a PhD in economics from Harvard and held various academic positions before joining the Ford Foundation as director of higher education in 1967. During Chamberlain’s tenure at Ford, her grantmaking seeded the nation’s first women’s studies departments, funded research on and by women in education, and created the National Women’s Studies Association and the Feminist Press. The April 2013 New York Times obituary remembered Dr. Chamberlain as “the fairy godmother of women’s studies.”

Flora Rhind

Flora M. Rhind (1904-1985) rose from a secretarial position at the Rockefeller Foundation to principal officer at a time when few women held formal leadership roles in foundation philanthropy. Her career with three Rockefeller philanthropic organizations–the Rockefeller Foundation, Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (LSRM), and General Education Board (GEB)–spanned thirty-eight years (1926-1964) and was characterized by a devotion to educational and equal opportunity causes.

Elizabeth Paschal

Sometimes an understated Midwesterner in a string of pearls can make an enormous difference. Dr. Elizabeth Paschal (1902-2006), a labor economist, served as “executive associate” of the Ford Foundation’s Fund for the Advancement of Education beginning in 1951. For more than a decade, until her retirement in 1964, she spearheaded the Fund’s and later the Ford Foundation’s efforts in school desegregation and did much of her work just as the US civil rights movement heated up.

Nie Yuchan (Vera Nieh)

Nursing education globally was a large undertaking of the Rockefeller Foundation begining in 1918. In 1940, in China, Nie Yuchan (also known as Vera Nieh, 1903-1998) became the first Chinese person (and first woman) to serve as dean of the Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) School of Nursing.“Nurses – Memorandum,” China Medical Board records, Rockefeller Archive Center.In that role, Dean Nieh became an outspoken advocate for her students, often confronting and directly challenging China Medical Board director Dr. Claude E. Forkner. (The China Medical Board was created by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1914, and established the PUMC.)

Forkner was not the only one she challenged. In 1941, Nieh convinced Japanese soldiers who were raiding her campus to wait quietly in the hallway for two hours while her students completed their national exams for professional qualification. She later explained that it was wartime, and her newly trained nurses would not be able to help in the war effort without proper qualifications.See also Sonia Grypma, China Interrupted: Japanese Internment and the Reshaping of a Chinese Missionary Community. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2012.The Japanese occupation eventually forced PUMC nursing students and faculty off campus — and Dean Nieh led them on a 1,000 mile march into Free China to reopen the school at West China Union University in Chengdu for the duration of the conflict. She also led faculty and students into the occupied area to help compensate for nursing shortages in the war zone. Nicole Elizabeth Barnes, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s China Medical Board and Medical Philanthropy in Wartime China, 1938-1945.” RAC Research Reports, 2009, p.3.These and other decisions she made demonstrated a degree of autonomy that unsettled Dr. Forkner and many male administrators, who described her as “out of order” and “insubordinate.”

PUMC Nursing School alumnae and the administrators who worked for Dean Nieh thought quite the contrary. When the China Medical Board’s all-male Wartime Advisory Committee tried to fire Dean Nieh, these women wrote a strong letter of support. “We beg to assure you, Sir, that in our humble opinion we can find no better qualified person than Miss Vera Nieh for the deanship,” they wrote on May 3, 1944. “[W]e take the liberty to request you […] entrust to Miss Nieh the responsibility for the administration of the School.” Nieh stayed on at PUMC, continuing to serve even after the school was nationalized by the Communist government in 1949.Nicole Elizabeth Barnes, “Authority in the Halls of Science” in Intimate Communities. Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China, 1937-1945. University of California Press, 2018, pp.120-158; Nicole Elizabeth Barnes, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s China Medical Board and Medical Philanthropy in Wartime China, 1938-1945.” RAC Research Reports, 2009; Dewen Zhang, “Rockefeller Foundation and China’s Wartime Nursing, 1937-1945.” RAC Research Reports, 2009.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (1874-1948), the matriarch of the Rockefeller family’s second generation, founded New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1929 with friends Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan, giving modernism a dedicated showcase. Alongside her husband, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Abby Aldrich Rockefeller built a veritable philanthropic empire, creating myriad organizations, amassing and donating both art and land, and restoring historic landmarks. In addition to her steadfast patronage of the arts (in addition to modern art, folk art was a favorite), Abby Rockefeller also supported the YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association) of New York, the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, the Grace Dodge Residential Hotel for women war workers in WWI, and she served on committees at Riverside Church, International House, and other non-profit organizations.

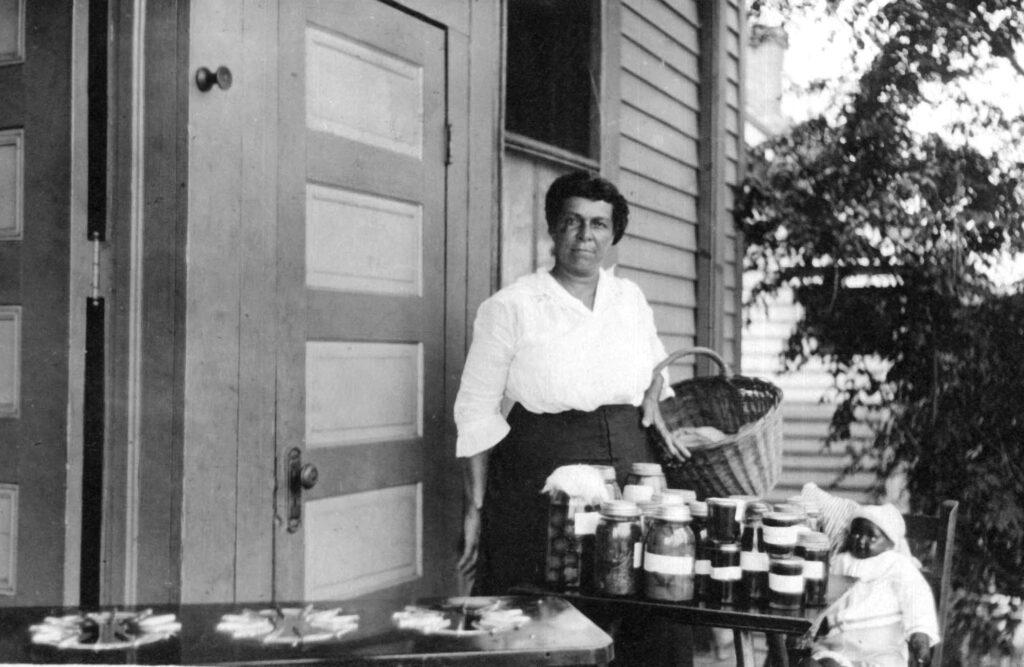

Mabel Myers and Stella Richards

Mabel Myers and Stella (Estelle) Richards served as district agents for home makers clubs in the American South. These clubs, sometimes referred to as “canning clubs,” began in 1914 through the USDA. Myers and Richards were the first Black female agents in the Southern regional office, hired in Tennessee to run a separate program for Black women (USDA programs adhered to the Jim Crow segregation laws in place in the South at the time). Because white-controlled local governments often were reluctant to invest in Black programs, the General Education Board, a large, Rockefeller-funded philanthropic foundation, took up the task. It supported an experimental program of home makers clubs run by the Tuskegee Institute, and its funding enabled county extension offices in Southern states to pay the salaries of the many Black demonstration agents that Myers’ and Richards’ program relied on, without turning to local governments.The General Education Board was incorporated in 1903 to foster “the promotion of education within the United States of America, without distinction of race, sex, or creed.” John D. Rockefeller, Sr., made an initial commitment of $1 million to the organization, but his contributions quickly grew to $43 million by 1907. Through these clubs and training activities, Myers and Richards emphasized Black self-sufficiency, hoping to empower African American Southerners and close the racial gap in nutrition, housing, and other living conditions.Mary Hoffschwelle, Rebuilding the Rural Southern Community: Reformers, Schools, and Homes in Tennessee, 1900-1930. University of Tennessee Press, 1998, pp.107-116. See also Mary S. Hoffschwelle, “‘Better Homes on Better Farms’: Domestic Reform in Rural Tennessee.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2001), pp.51-73.

Daphne Culpeper

Following the 1940 death of her prominent husband, Charles E. Culpeper, who founded and for many years led the Coca-Cola Bottling Company in New York City, Daphne Seybolt Culpeper (1891-1976) of Norwalk, Connecticut devoted much of her remaining years to charitable and philanthropic causes. With no living relatives when she died in 1976, Mrs. Culpeper made sure in her will that her estate would be used to establish the Daphne Seybolt Culpeper Memorial Foundation, to benefit not-for-profit organizations in the two states where she had her homes, Connecticut and Florida. The Foundation works in education, health care, and human services.

Mary Richmond

Social worker Mary Richmond (1861-1928) was director of the Charity Organizational Department of the Russell Sage Foundation beginning in 1909.“Charity Organization Department,” Russell Sage Foundation records, Early Office Files, Series 3, Rockefeller Archive Center. In this role, Richmond built a network of social workers and conducted research on women and families. She was revolutionary in her emphasis on social environment, rather than individual “deficiency” as the cause of social problems.Mary Ellen Richmond (1861-1928) – Social Work Pioneer, Administrator, Researcher and Author.” Social Welfare History Project. Richmond pioneered the methodology for case work that social workers still use today.

Anna Harkness

Anna M. Harkness (1837-1926) established the Commonwealth Fund in 1918 to do “something for the welfare of mankind.”Anna M. Harkness, The Commonwealth Fund.The financial and social support she set in motion with the Fund has bolstered a large number of institutions in the century since its founding. The Fund has been a leader in health care, building rural hospitals, pioneering new approaches to infant and maternal care, working create better access to health care for disadvantaged populations, bringing hospice care to the US, funding medical fellowships (as well as the renowned non-medical Harkness Fellowships), providing key data to inform health policymakers, most signally toward the Affordable Care Act, and even inventing the professions of physician’s assistant and nurse practitioner. Anna Harkness also made substantial donations to the Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes in support of education for African Americans, in addition to major gifts to Yale University, the New York Public Library, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among many other institutions. One of her most generous endowments was her donation of a 22-acre stretch of land in upper Manhattan, given to Columbia University for a new medical center for the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage

Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage (1828-1918), a multi-millionaire widow who preferred to be called “Mrs. Sage,” created the Russell Sage Foundation in 1907 for “the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States of America.” The Russell Sage Foundation was one of America’s earliest large, multi-purpose, private foundations, and the first to be established by a woman.See Ruth Crocker, Mrs. Russell Sage: Women’s Activism and Philanthropy in Gilded Age and Progressive Era America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008. One of its early innovations was the concept of “investment philanthropy,” where philanthropic funds were used to support for-profit projects doing social good. Between 1907 and 1946, the Foundation focused on exposing social problems and proposing and sponsoring practical solutions for those problems, often through producing publications. Areas of study included public welfare, labor and industrial relations, regional planning, crime and prison management, child welfare, and the social work profession. In 1948, the Foundation reorganized and shifted its focus to basic research in the social and behavioral sciences and the strengthening of social welfare methodology, work it continues today.