Between 1865 and 1910, an estimated 40% of the population in the US South suffered from hookworm disease.John Ettling. The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South. (Cambridge, MA: The Harvard University Press, 1981), 2.The disease stunts growth, makes its victims more prone to other infections, and causes extreme fatigue. Some have even claimed that the sluggishness caused by hookworm was a factor in the South’s defeat in the Civil War. Yet for decades most southerners neither knew nor cared about hookworm. Since it rarely caused death directly, its effects were more or less accepted as part of normal life.

Nevertheless, two key northerners did not accept hookworm to be a fact of life. Philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and his adviser, Frederick T. Gates, started a campaign against hookworm that would in time go well beyond single disease control.

In fact, the results of the work battling hookworm would help launch the US public health system in the South. Moreover, the work on hookworm came to provide the basic protocol for the Rockefeller Foundation (RF)’s global public health campaign. That campaign lasted almost 40 years against diseases far more dire.

Hookworm’s Public Health Legacy

In 2020, a global pandemic has caused many of us to think about public health systems for the first time. Few realize, however, that many of the building blocks for these systems were actually laid out over a century ago in one philanthropy’s campaign against hookworm.

The basic elements might now sound quite familiar. They include making the public understand that a threat is real, testing to figure out the extent of an illness, and mapping the spread of infection. But the hookworm records of a hundred years ago also reveal that public health campaigns can cause strained relationships among communities, government, and philanthropy as people grapple to respond. The events of 2020 show that equally strained relationships can happen today.

Hookworm: The Germ of Laziness

How could a disease as widespread as hookworm go unnoticed? As an RF publication would later explain:

[T]his disease is never spectacular, like yellow fever or plague or pernicious malaria. It is the greater menace because it works subtly…hookworm disease, working so insidiously as frequently to escape the attention even of its victims, tends to weaken the [human] race by sapping its vitality.Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1915, 47.

To be fair, the disease’s pathway was not fully known or described until 1896. But surprisingly, its discovery received only minor attention for more than ten years. Furthermore, that attention served mainly to promote stereotypes of southerners as slow and lazy. In 1902, after hookworm was discussed at a medical conference, a New York Sun headline asked: “Germ of Laziness Found?”

The article went on to cast hookworm as a disease of “crackers” (a slur against poor, rural whites) and “other nations.”Ettling, 35-6.

Philanthropy and the South

In 1909, John D. Rockefeller established the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease (RSC) with a gift of $1 million. Why would a northern philanthropist choose to mount a costly public health campaign against an obscure southern plague?

And why would he do it when no one asked for help in the first place?

For one thing, the Rockefeller family had a history of working in the region. Rockefeller’s wife, Laura Spelman Rockefeller, came from a family of northern abolitionists who had campaigned to end slavery in the South. In fact, Rockefeller funded a seminary for African-American women in Atlanta, which was renamed Spelman College in honor of his in-laws.

Yet the search for ways to make a difference in the South went beyond the Rockefellers’ personal feelings. At the turn of the twentieth century, the contrast between the industrial North and the rural South was stark. Many northerners who made their fortunes in industry set their sights on helping make the poorer South more modern. In turn, many southerners felt wary of this help.

Rockefeller’s son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., witnessed southern poverty first-hand in 1901. He rode on the “millionaire’s special,” a fact-finding train trip hosted to drum up support from wealthy northerners. He then convinced his father to found the General Education Board (GEB) in 1903. The GEB aimed to improve education throughout the region. Its mission stated it would do so “without distinction of race, sex or creed.”

The Missing Link: Public Health

But there was one problem that GEB staff could not solve. Financial gifts to build new schools and hire more teachers couldn’t address hookworm victims’ lack of energy. Infected children were malnourished, undersized, riddled with other health problems, and unable to focus in school. Their infected parents were often unable to work. Families and communities lived in a cycle of poverty that was driven in part by hookworm.

What is Hookworm Disease?

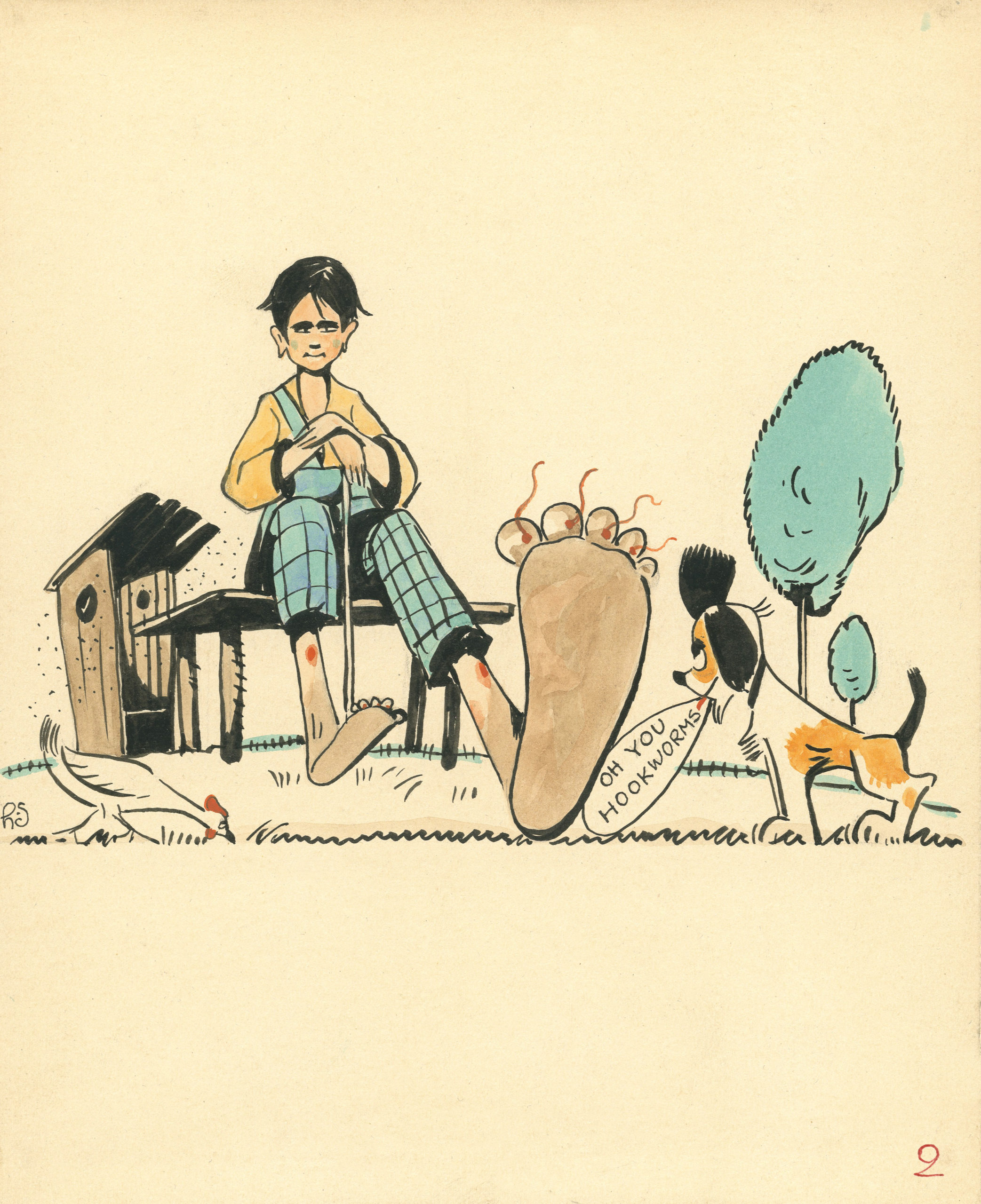

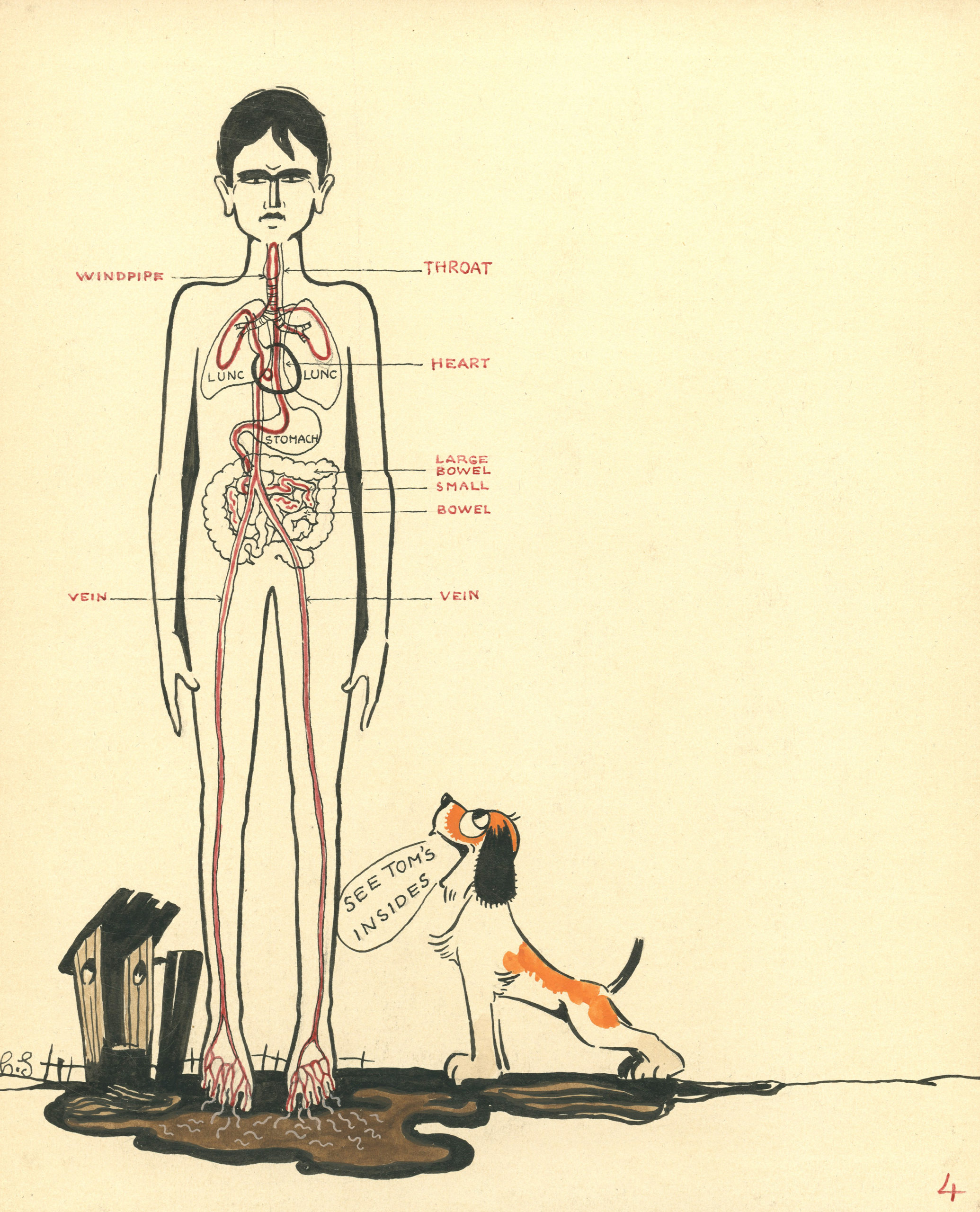

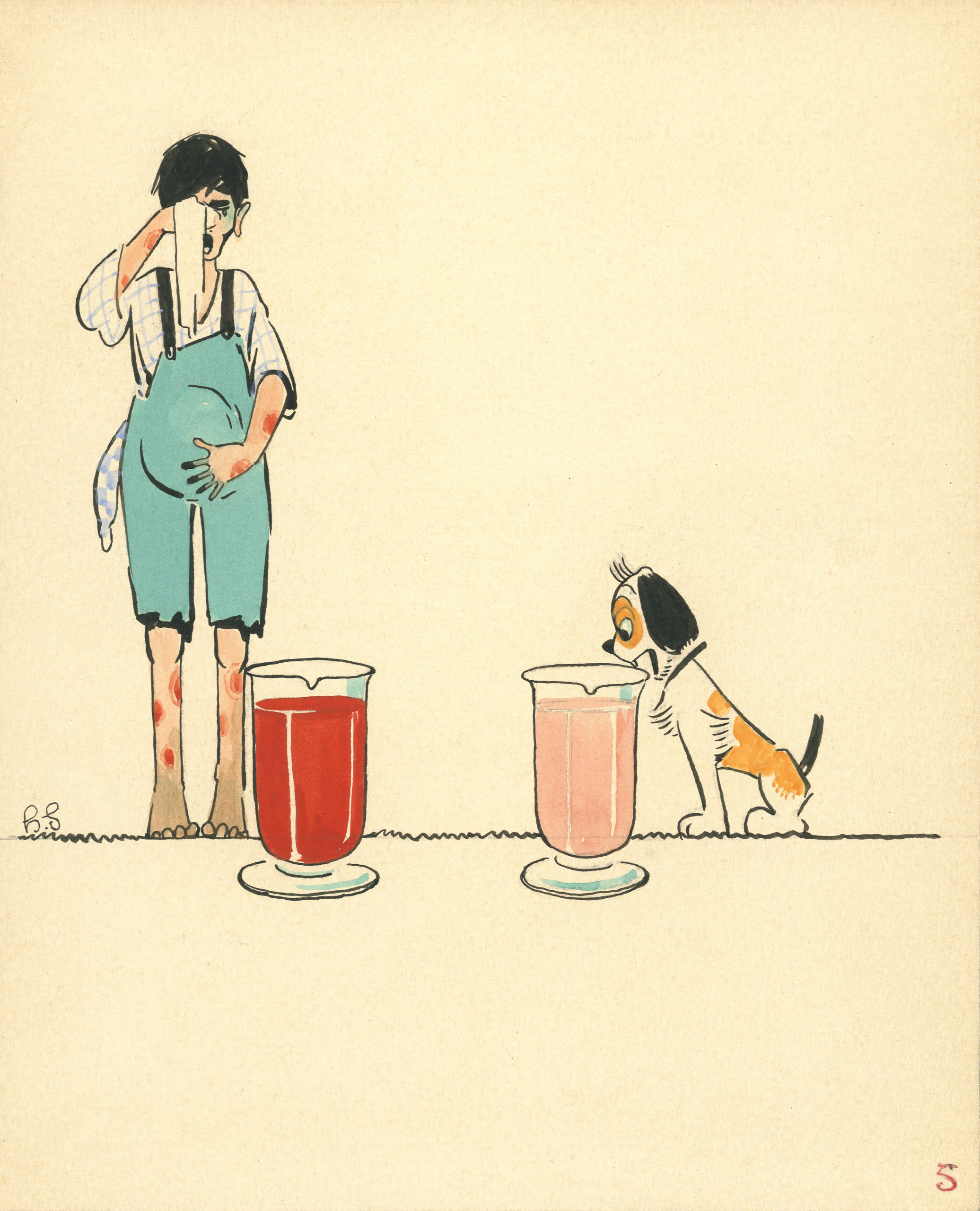

Hookworm disease begins when microscopic parasites enter the body through the skin – usually between the toes of bare feet. Southerners called the feeling of it “ground itch.” The tiny worms enter the bloodstream, go to the lungs, and from there make their way into the bronchial passages. Once in the throat, they are swallowed and enter the gastrointestinal tract. The worms lodge in the intestines, feed on the host’s blood, and lay tens of thousands of eggs. These eggs pass out through a person’s feces. Where no proper privy is in place, the feces end up in the soil. The eggs hatch and the cycle begins all over again.

Climate in the North prevents the conditions that hookworm larvae need to survive in the soil. But worldwide, the tropical and sub-tropical belt between degrees of latitude 36 north and 30 south is the hookworm’s native habitat. This includes the US South and all or part of more than two dozen nations. More than half of the world’s population lives in this band.

And yet treatment of the disease is fairly simple.

Solving a Simple Problem Through Public Health

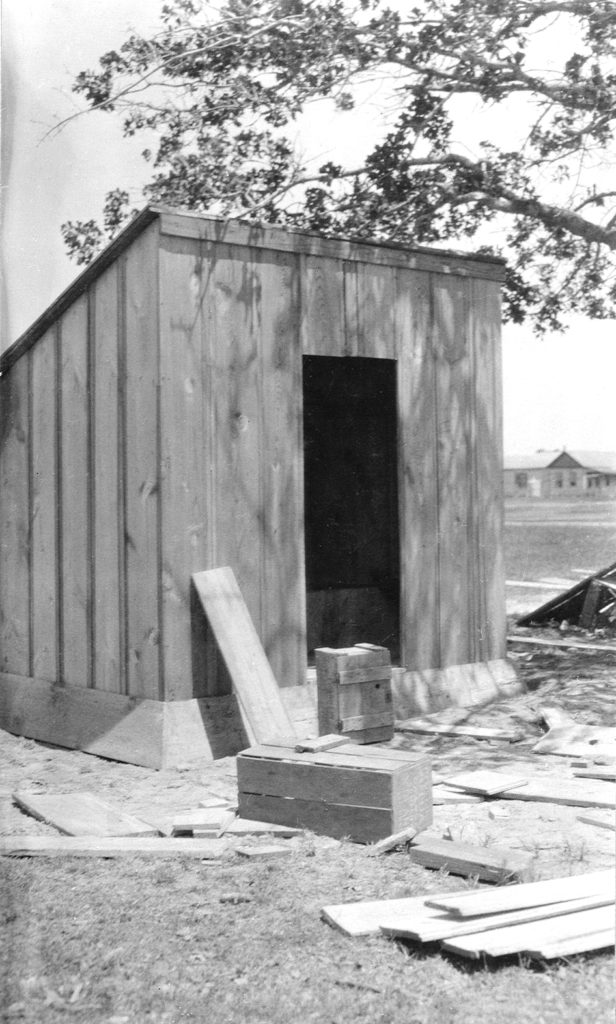

There are three ways to keep the disease at bay. First, treat infected people so that their feces will no longer contain eggs. At the time, Thymol and Epsom salts were the cure. They worked within 24 hours. Second, convince people to build safer privies. These prevent fecal matter from leaking into the soil in the first place. Third, convince people to wear shoes year round. Shoes protect feet from worms that have escaped the other measures. They also guard against second waves of infection.

Seems simple enough.

In fact, Rockefeller and his team chose to focus on hookworm because it is indeed simple — and solvable. As John A. Ferrell, state director of North Carolina’s program, explained, “it is both preventable and curable by methods the simplicity of which appeals to everyone. The results following treatment are so prompt and emphatic that they have been aptly compared with the miracle of the New Testament.”Ettling, 203.

Stopping an Epidemic: Not Truly Simple?

The new commission’s very name seems to declare its goal. But in reality, the leaders of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease did not intend to eradicate the disease. Hookworm is easy to treat and prevent. Yet without total and continued containment, it will always return. And the human factor, even in a simple situation, complicates everything.

The RSC’s first discovery was that getting people to cooperate was hard. Many Southerners, for example, did not believe in the ailment despite the facts. Others would rather live with its effects than take medication. This made a goal of total compliance almost futile. Furthermore, some communities, sensitive to the “cracker” stereotype, resisted privies because they looked too primitive, and preferred to use the bushes. Some people enjoyed going without shoes in the summertime. Others could not afford shoes.

And, finally, then as now, people found it hard to stick with long public health campaigns and small changes in habit.

The word eradication gave the RSC an air of drama, but victory over hookworm would be an endless, tedious slog to enact simple steps. Indeed, it would never even bring total victory. So anything that inspired southerners to feel like the fight was an urgent, high stakes battle helped.

The results following treatment are so prompt and emphatic that they have been aptly compared with the miracle of the New Testament.

John A. Ferrell

An Object Lesson in Public Health

Instead of focusing on a doomed quest for eradication, RSC leaders aimed for something larger and longer-lasting. They saw hookworm as an opening wedge that would prompt government to develop a public health service. RSC director Wickliffe Rose explained this idea a few years later, when the RSC work transferred to the Rockefeller Foundation. “By showing that it is possible to clean up a limited area,” Rose wrote, “an object lesson is given, the benefit of which is capable of indefinite extension.”Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1915, 14.

Rose believed treating hookworm could offer more than ending one disease. “The sanitary improvements that are brought about by the hookworm campaign tend to diminish typhoid fever and other intestinal diseases,” Rose argued.

“Moreover,” Rose went on, “a public health administration that has been organized or re-animated to deal effectively with hookworm disease has in that very process become a more efficient protector of the community against all other diseases susceptible of control.”Ibid, 16.

Getting People to Take Health Risks Seriously

To start, the RSC had to convince people that hookworm was enough of a problem to change their behavior. It even had to persuade some that the disease was a reality in the first place.

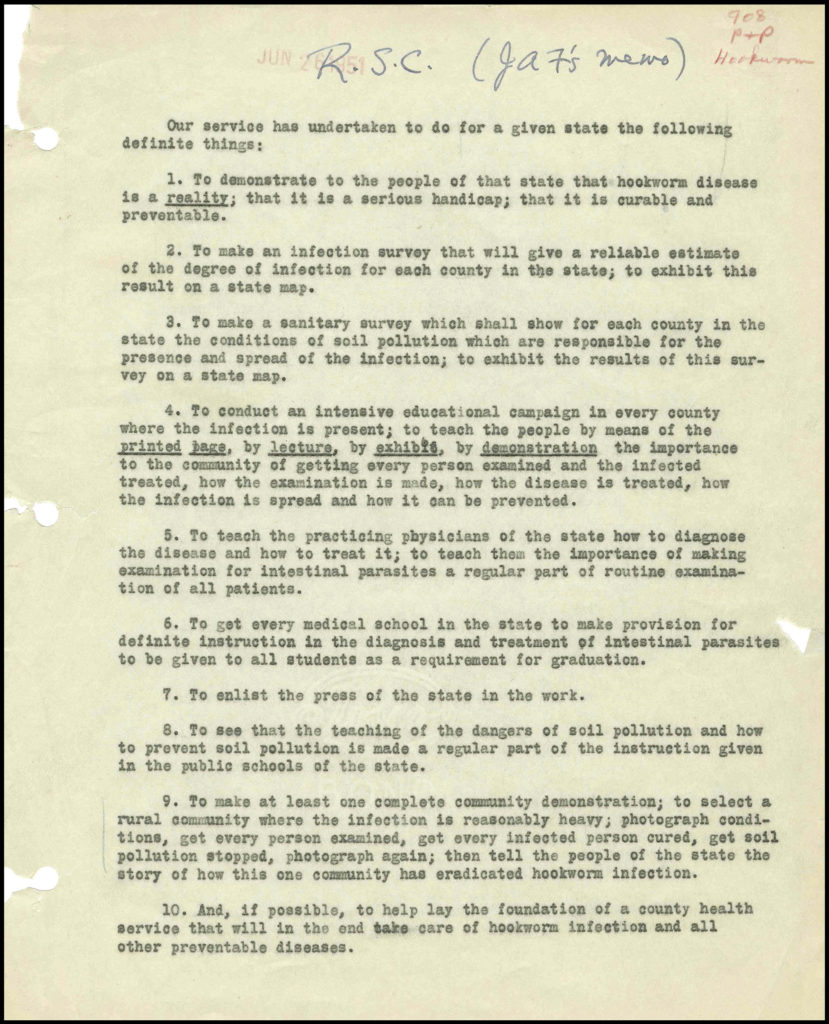

Ferrell crafted a memo that outlined the RSC plan. The memo’s ten points would serve as a blueprint for RF public health work for years to come. These basics extended to work on diseases including yellow fever, malaria, tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, and more.

First on the list was “to demonstrate to the people of that state that hookworm disease is a reality; that it is a serious handicap; and that it is curable and preventable.”

This topped the list for good reason. Many southerners thought the idea of eggs found in human stool was a hoax. They resisted help from the outside and they suspected that the “germ of laziness” was yet another way for the North to insult the South.

…to demonstrate to the people…that hookworm disease is a reality.

John A. Ferrell

How to Make Friends and Influence Public Health

In order to break down the widespread resistance, demonstrations and lectures became a huge part of the RSC approach. Hookworm was both predictable and not transmissible from person to person. Thus, live displays at state and county fairs and other public gatherings were perfectly safe. Also, hookworm never really went away. That made it ideal for endless demonstrations. As Ferrell put it, “its chronic nature renders it available for demonstrative purposes every day of the year in every community of the State.”Ettling, 203.

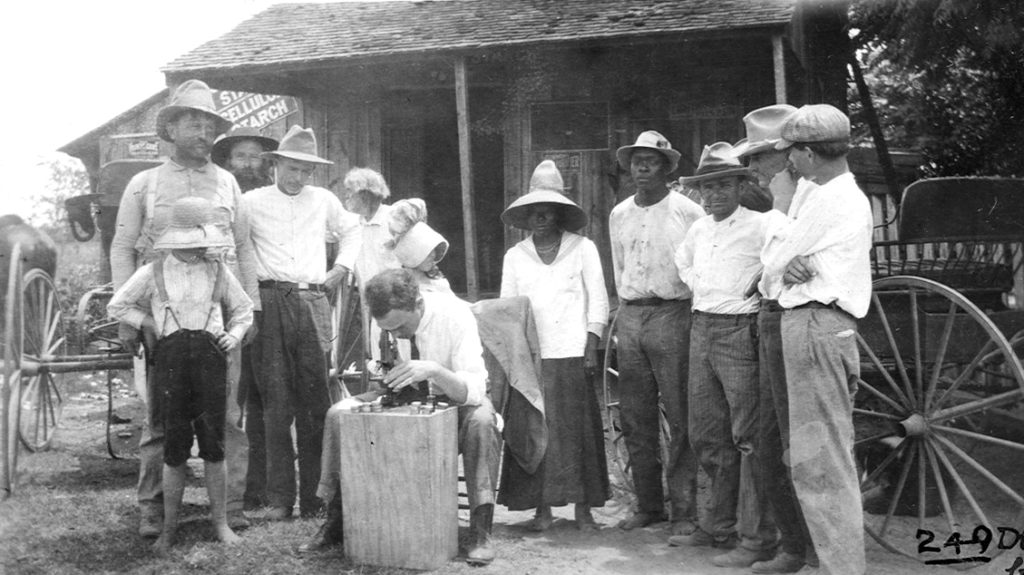

The RSC devised a system of traveling dispensaries. Staff would take stool samples from locals and examine them under a microscope on site. The crowds could see for themselves the eggs in the stool and be convinced. They then received medication and instructions to take home that same day.

Striking the right tone in the demonstrations was crucial.

Picking the Right Leaders

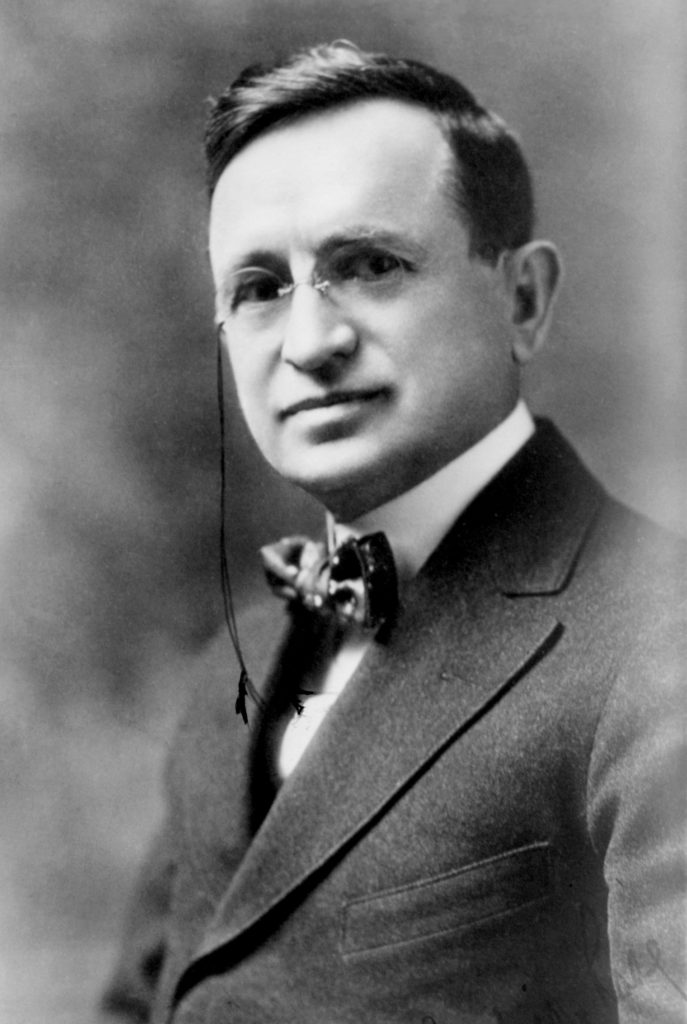

Setting that tone fell to the RSC leadership, so the RSC board took great care to find the right people. This led them down some odd paths. Rose, for example, was a philosophy professor by training. When the board tapped him to become the head of the new RSC in 1910, he was serving as dean of Peabody College and the University of Nashville.

Rose had key personal qualities that made him ideal to direct the project in the context of a resistant South. He was himself a southerner. Colleagues described him as modest, mild-mannered, and self-effacing. He understood that diplomacy was central to the RSC’s mission. In the end, the board selected Rose over several others to direct the RSC as its administrative secretary. One of those passed over was Charles W. Stiles, the scientist who had lobbied for a fight against hookworm for more than 15 years.

The Power of Persuasion

Stiles was one of two scientists who discovered hookworm in the mid-1890s. Trained in Europe, he went to work for the US Department of Agriculture in 1891, classifying animal parasites. In 1902, Stiles moved to the US Public Health Service to follow his growing interest in hookworm. He began reaching out to all who would listen on the need to combat the disease. Stiles presented a lantern slide show to everyone from town officials to state and national legislators and university presidents. Yet he did not have much luck. Even his own agency felt the need was not pressing.

As Stiles traveled the South, trying to win people to his cause, he was clumsy and often hurt his own chances for success. He helped mill owners, for instance, enforce treatment for their workers and never grasped why he could not win the support of labor. Also, in his public lectures, he failed to notice that he insulted country doctors by pointing out their lack of knowledge rather than enlisting them to become part of his movement.

Breakthrough

But in 1908, Stiles was able to show his slides to Wallace Buttrick, president of the GEB, and eventually to Frederick T. Gates, John D. Rockefeller’s closest adviser. Gates already had an interest in improving the field of medicine. While public health was not yet a fully formed or common concept, hookworm linked medicine with Gates’s other great quest — to create a type of philanthropy that would address the root causes of big problems in lasting ways.

For several years Gates had urged Rockefeller to practice “wholesale” rather than “retail” giving. Gates believed more good could be done through systems than through fleeting relief efforts. The southern situation with hookworm offered the chance to put public health systems in place that might have lasting effect.

Too Much Zeal for Public Health?

Without a doubt, Stiles’s work inspired the decision to create the RSC. Gates brought the idea to Rockefeller after meeting Stiles and tapping medical experts. But as things moved forward, Gates and the RSC board placed Stiles in a relatively minor position. Knowing that Stiles was abrasive and tone deaf in his zeal to make progress, Gates made him scientific secretary and kept him away from the Commission’s public relations arm. Yet public relations was the backbone of public health work.

So, as Rose’s RSC took shape, Stiles kept working mainly in mid-level positions at the US Public Health Service.

How Not to Do Public Health Work

Even in his federal post, Stiles made off-putting choices. He seemed to feel that shock value might convert the public into caring about hookworm. Gates and Rose continued to worry that his actions, while not coming from the RSC, would reflect on it anyway.

Stiles printed overly graphic pamphlets and often used scare tactics. While working on a campaign in Wilmington, North Carolina, he wrote letters to parents who had agreed to have their children’s stool samples tested. The letters explained that “the microscopic examination has given us evidence that Johnny has been eating food that has been contaminated, probably by flies, with human feces.”

Angry parents promptly lobbied the mayor and city council. After hearing from Wilmington’s health officer that his “life has been made a burden” by all the phone calls, Stiles made a proud report to Rose. “From the present conditions,” he boasted, “and the indignation of the parents, because of the fact that their children have actually been eating feces, I think it will soon be a sanitary town.”Letter from C.W. Stiles to Wickliffe Rose, July 17, 1913. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease records, Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center,

Such tactics were not Rose’s model.

Making Public Health Fun

Rose’s RSC moved carefully to install a team of trained doctors as envoys to each state. These men were native southerners, and were young enough that they could work for the RSC full-time without having to put a practice on hold. Thus, the medical community was part of the project rather than a target of its criticism.

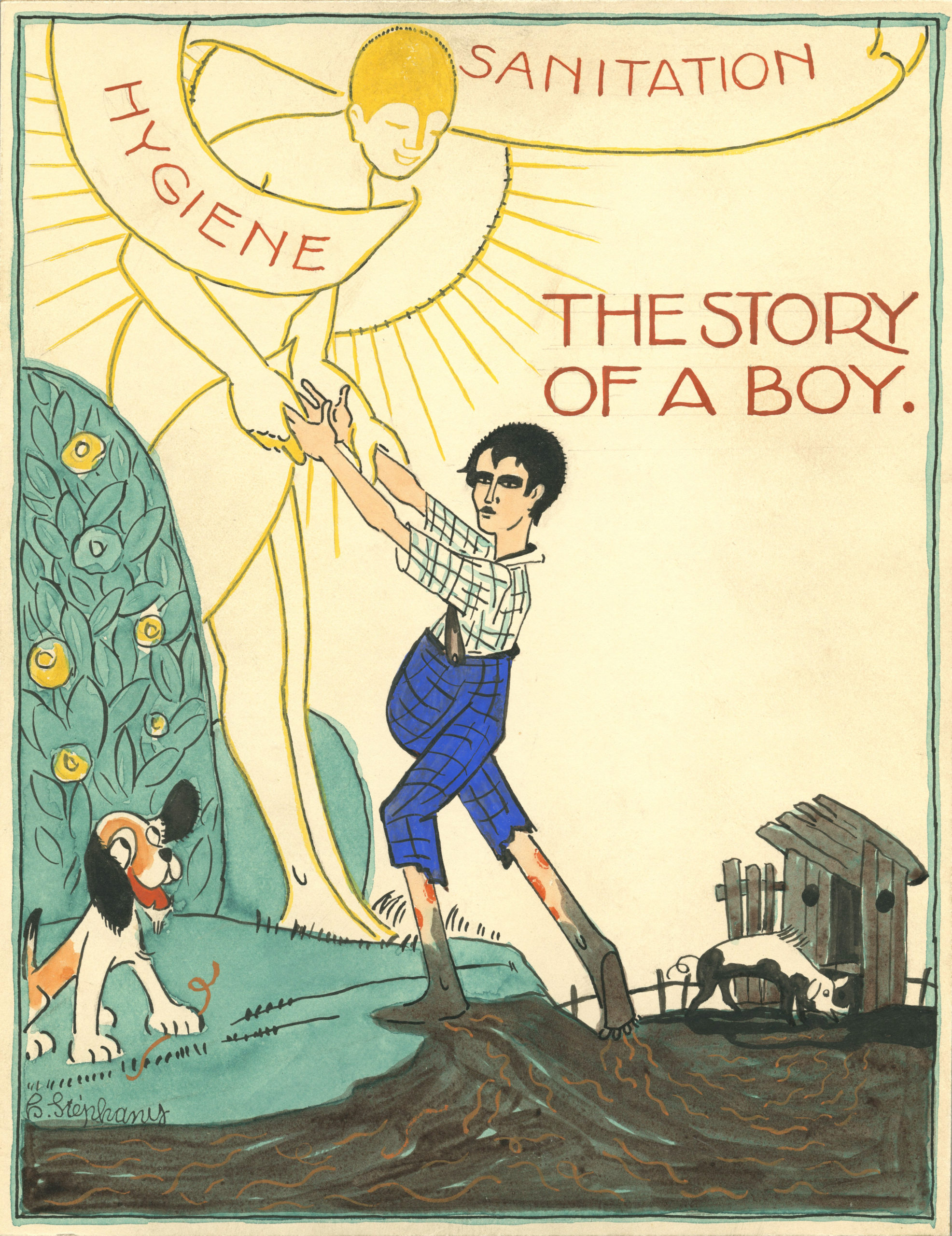

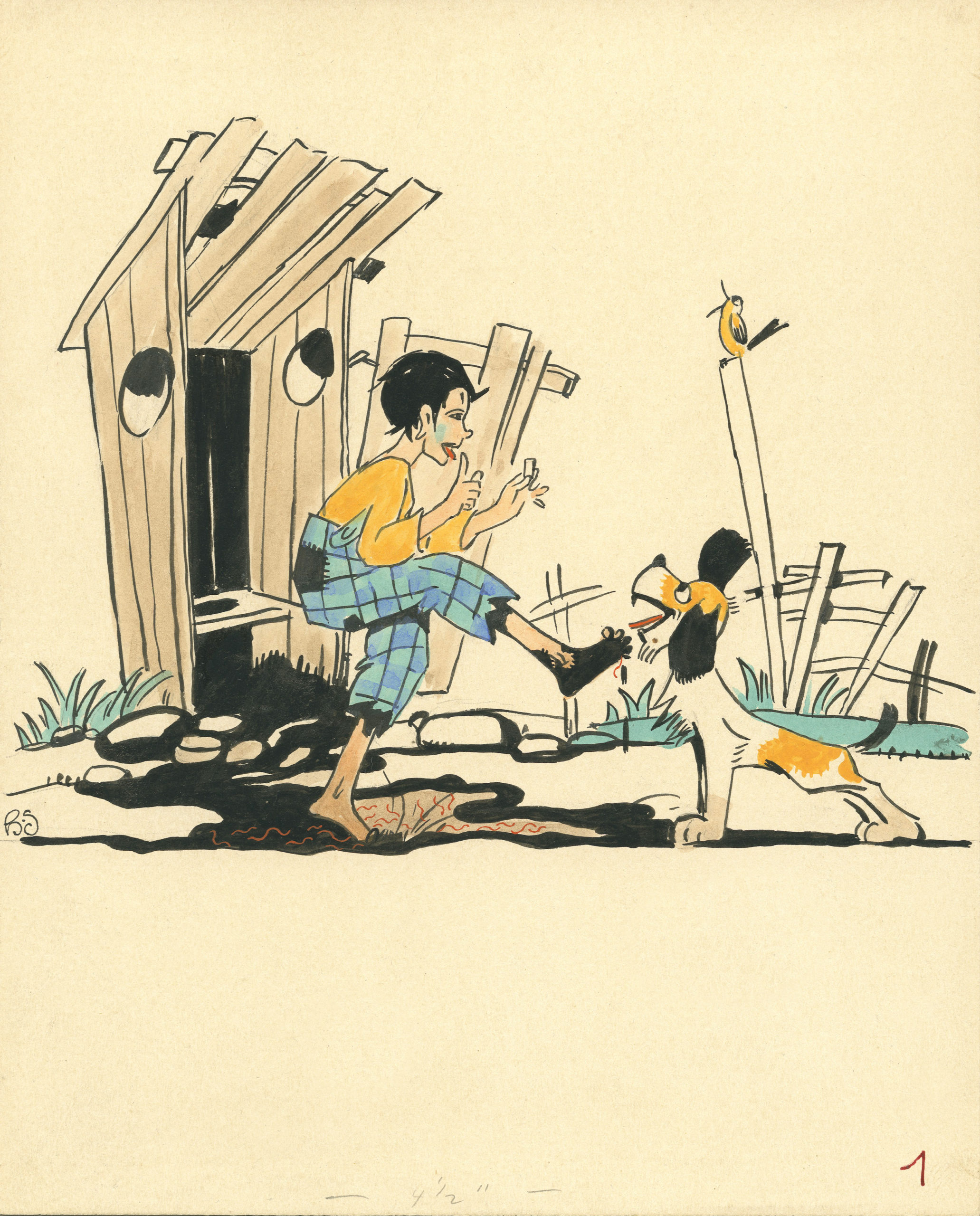

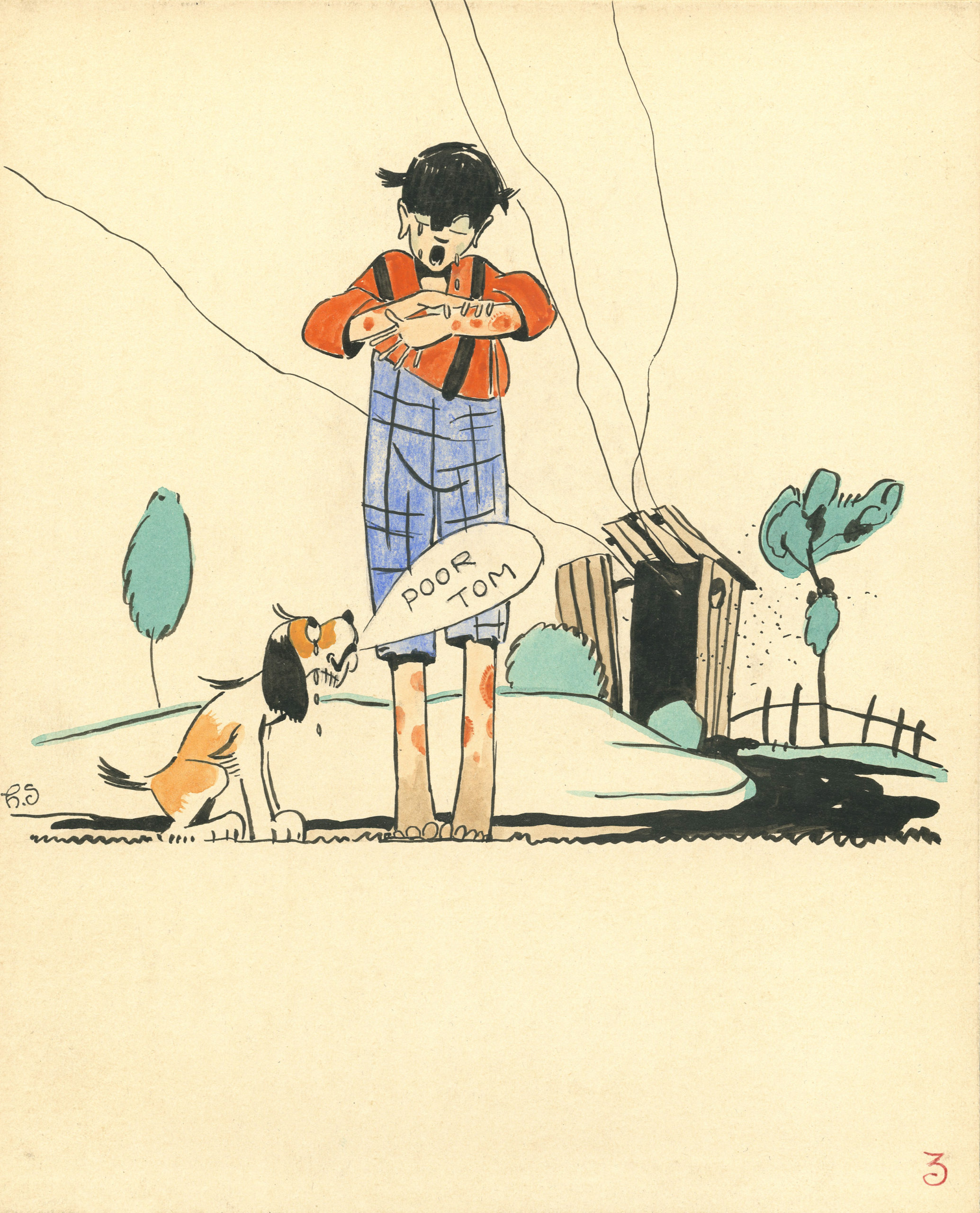

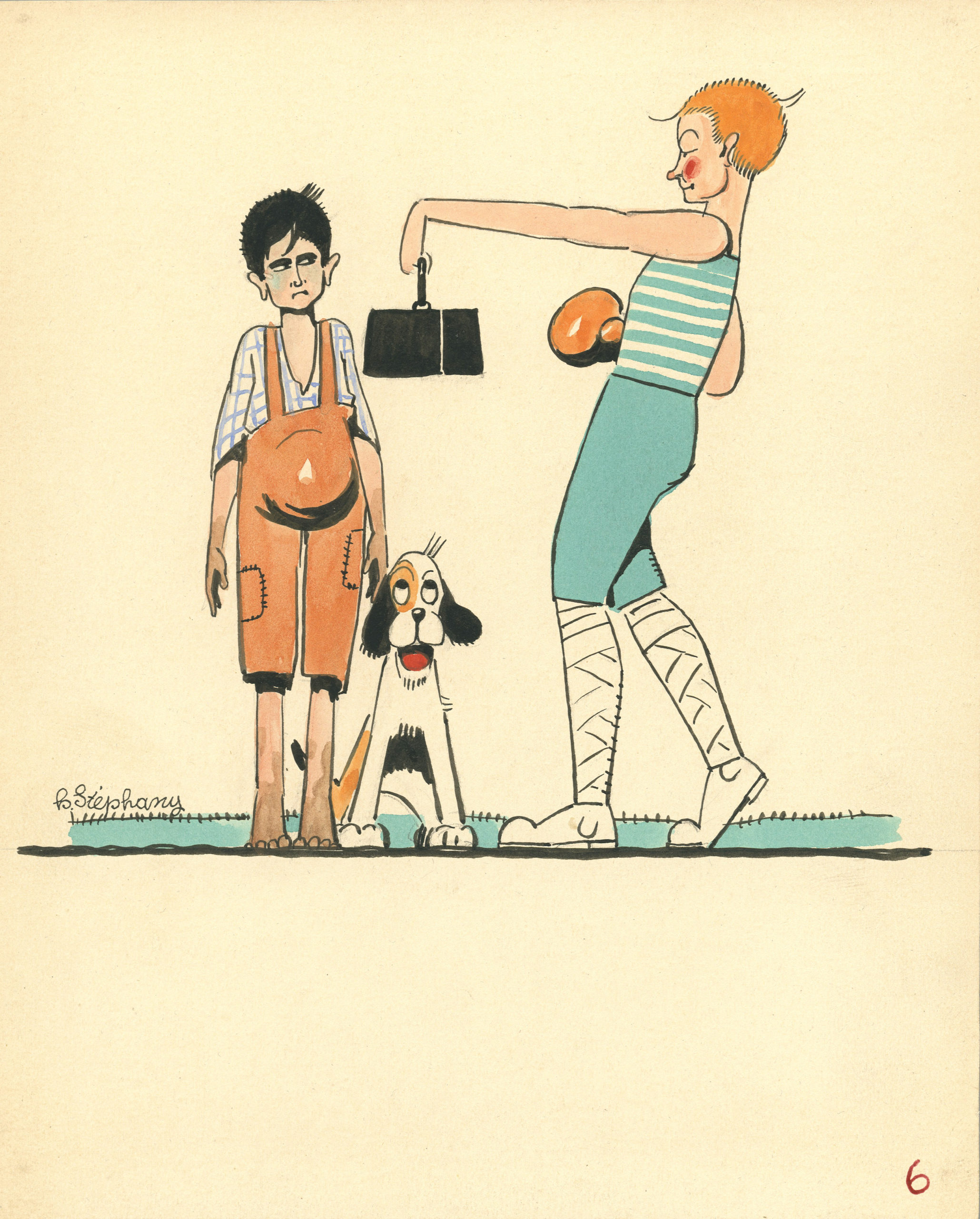

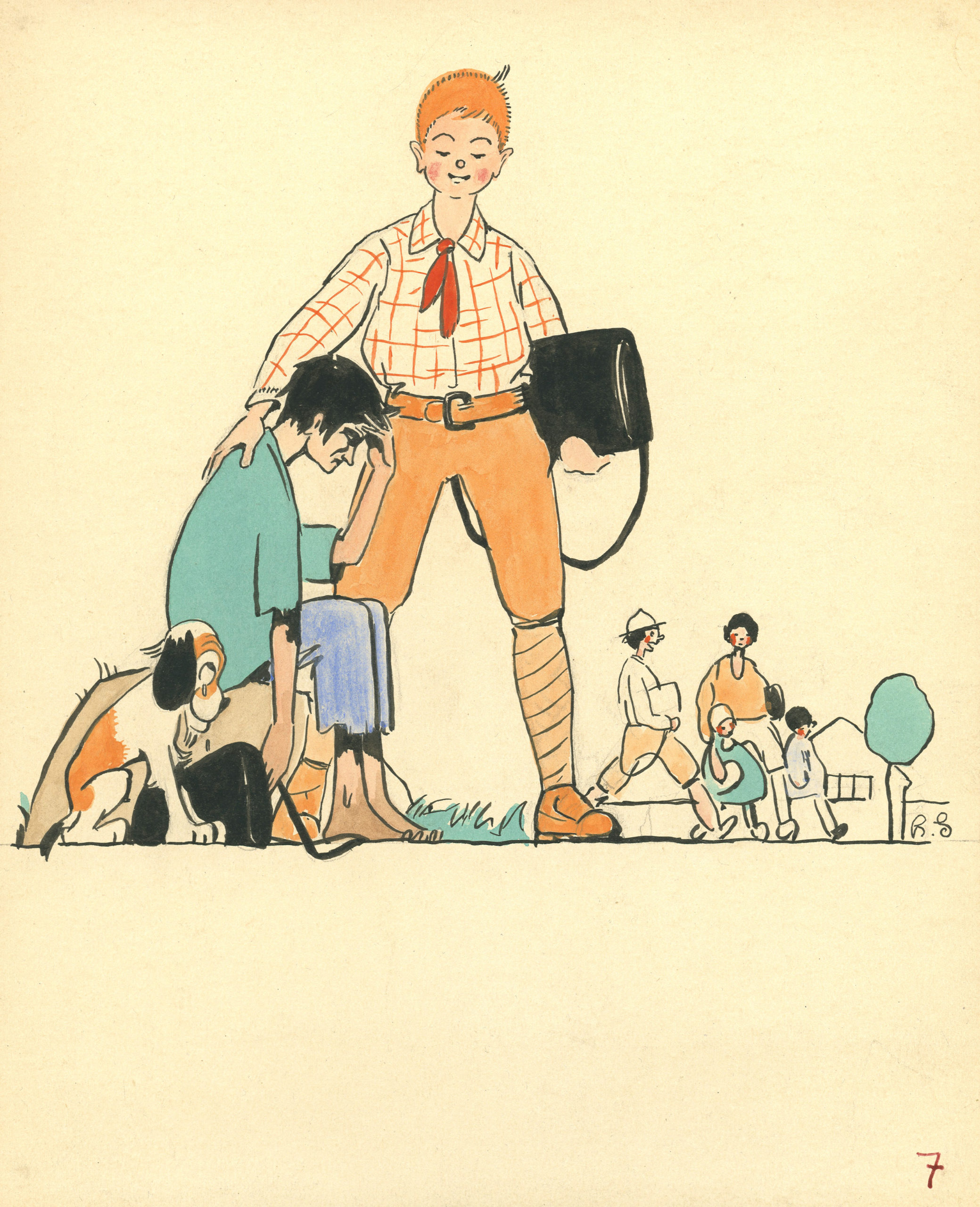

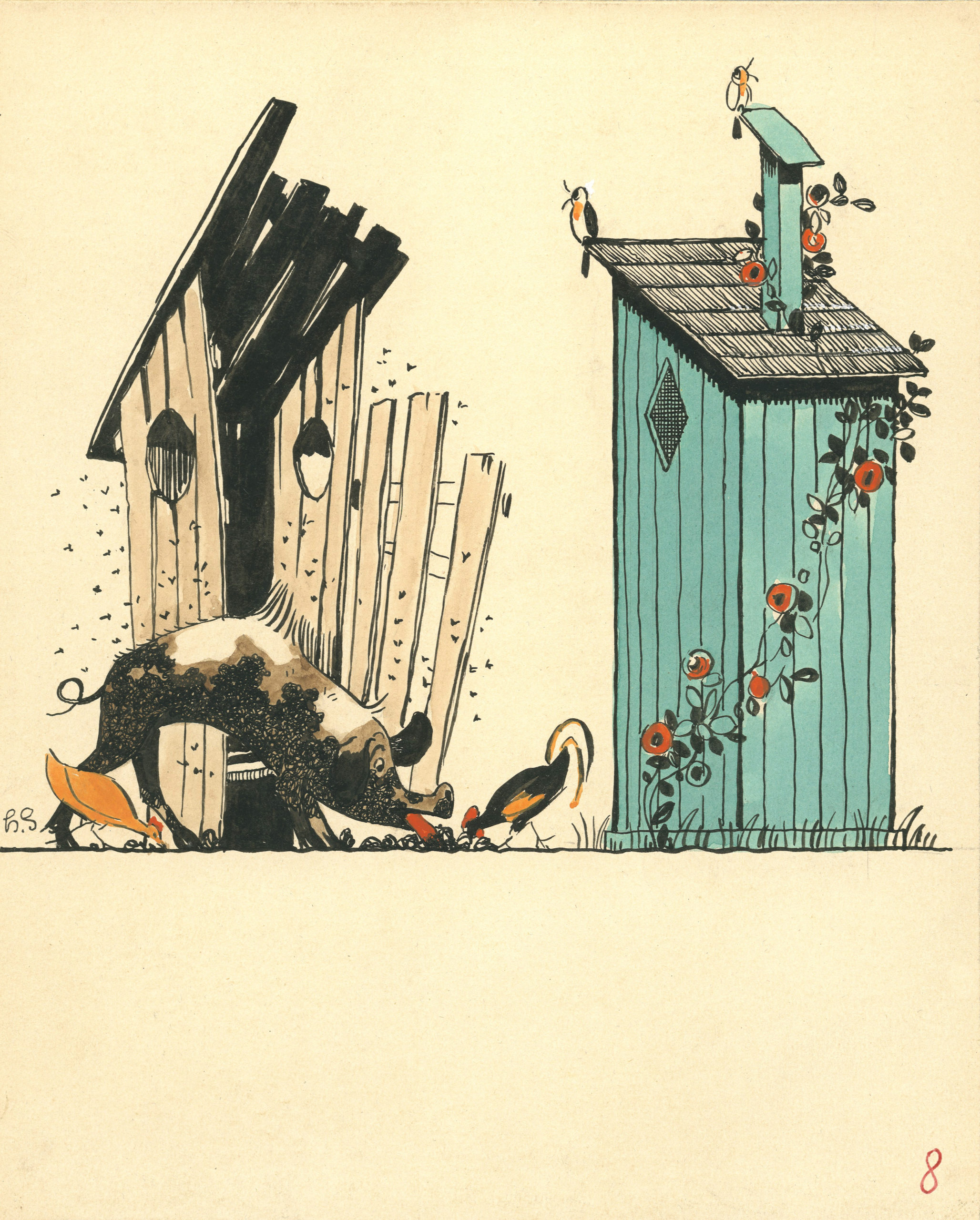

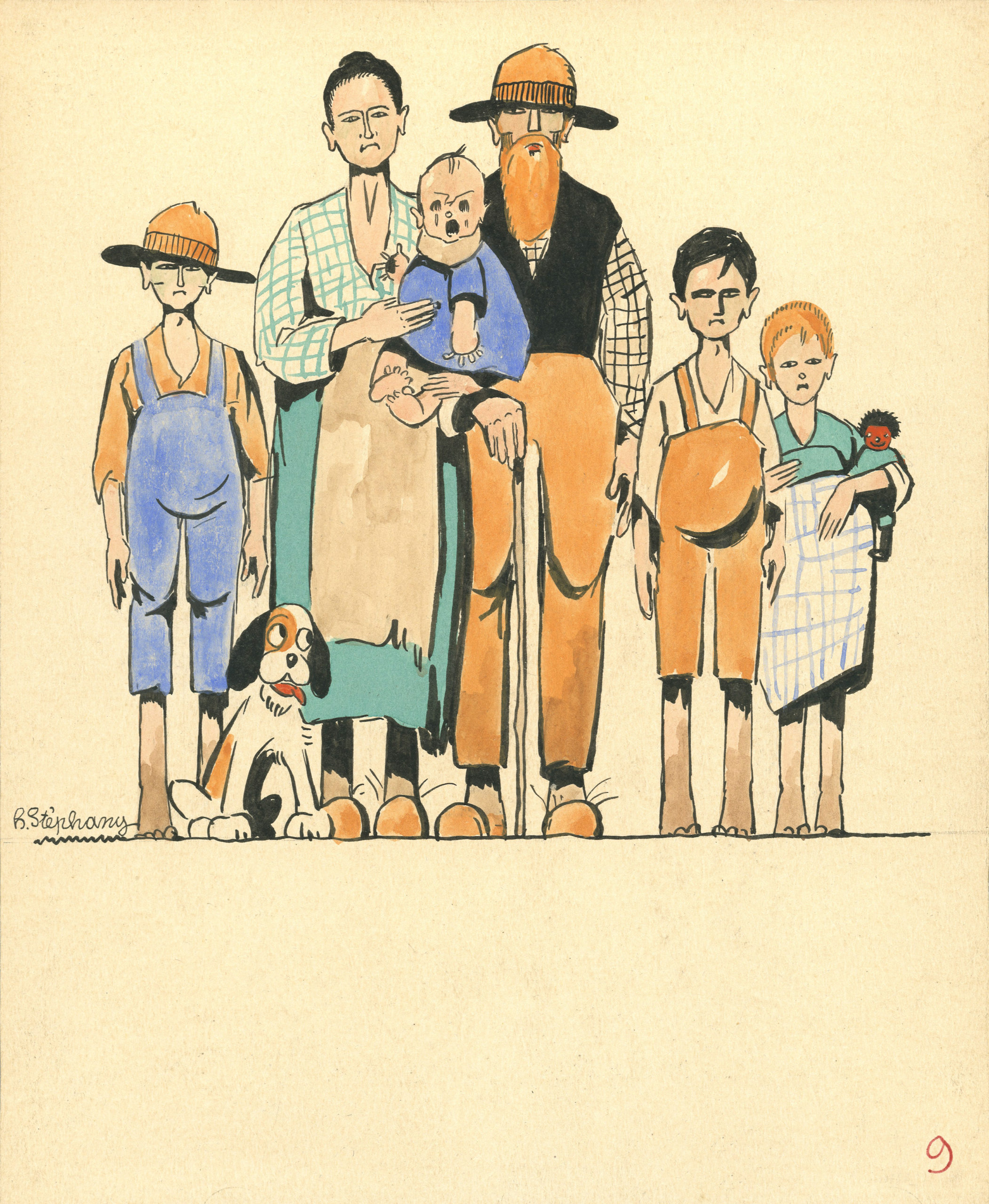

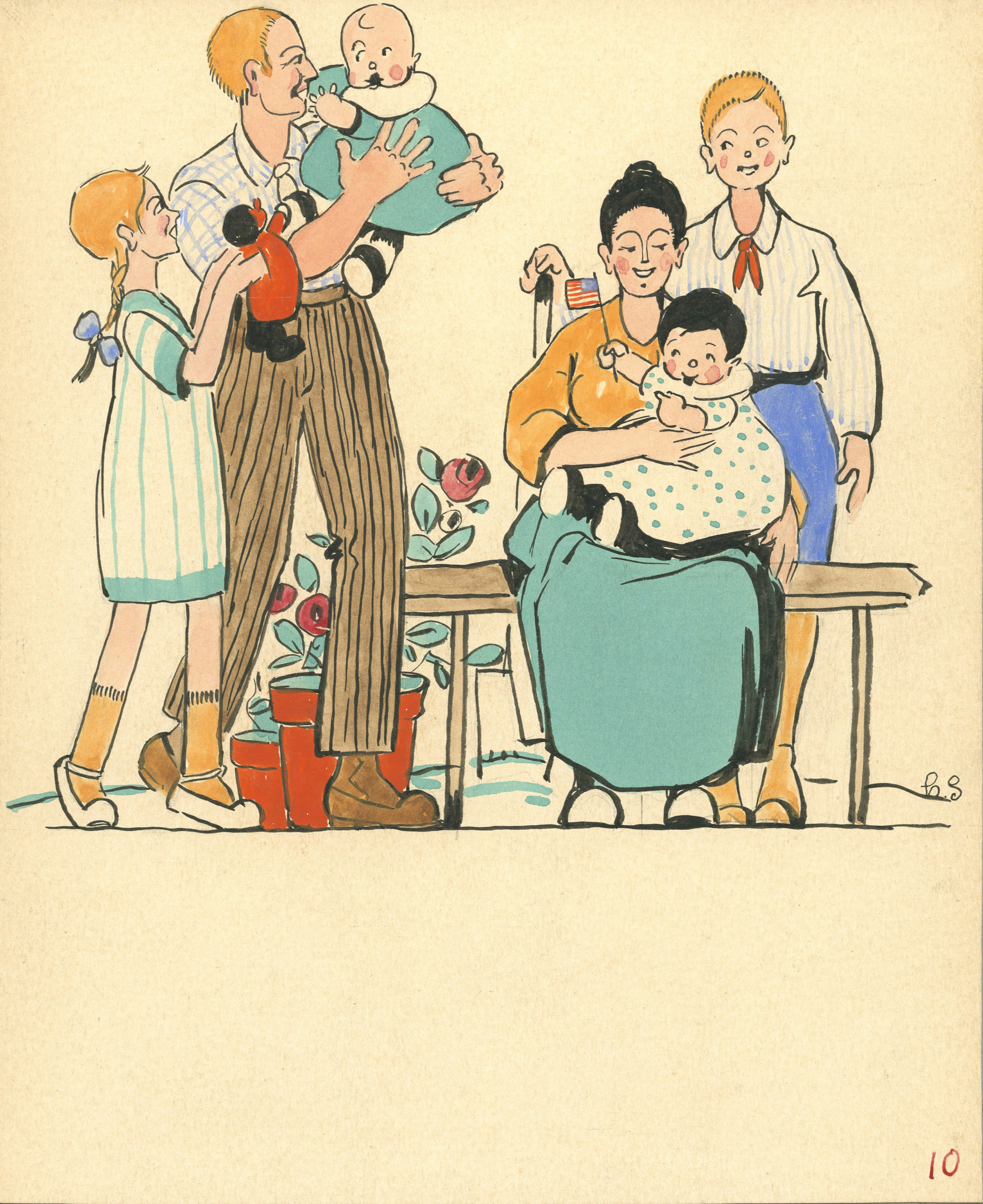

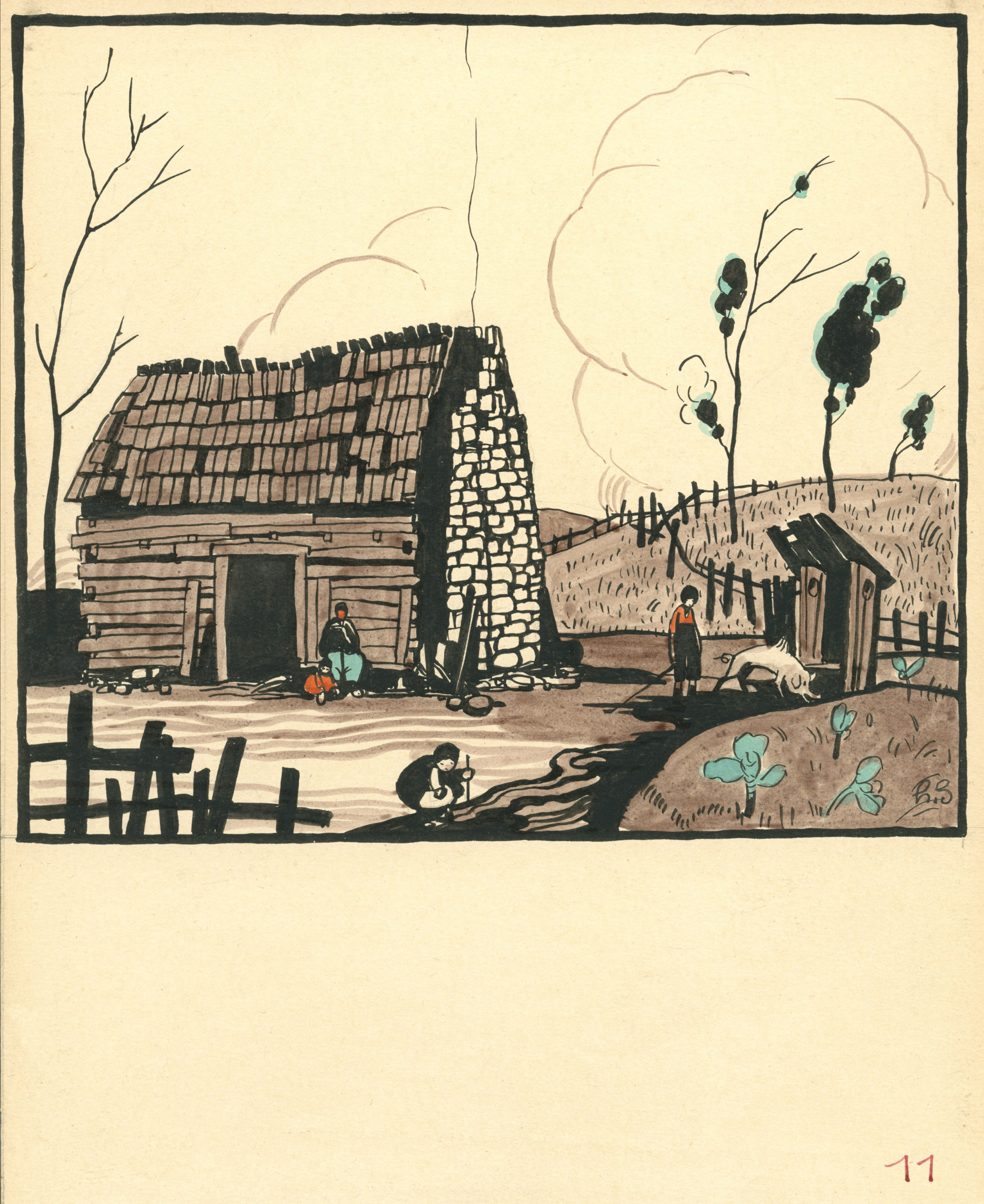

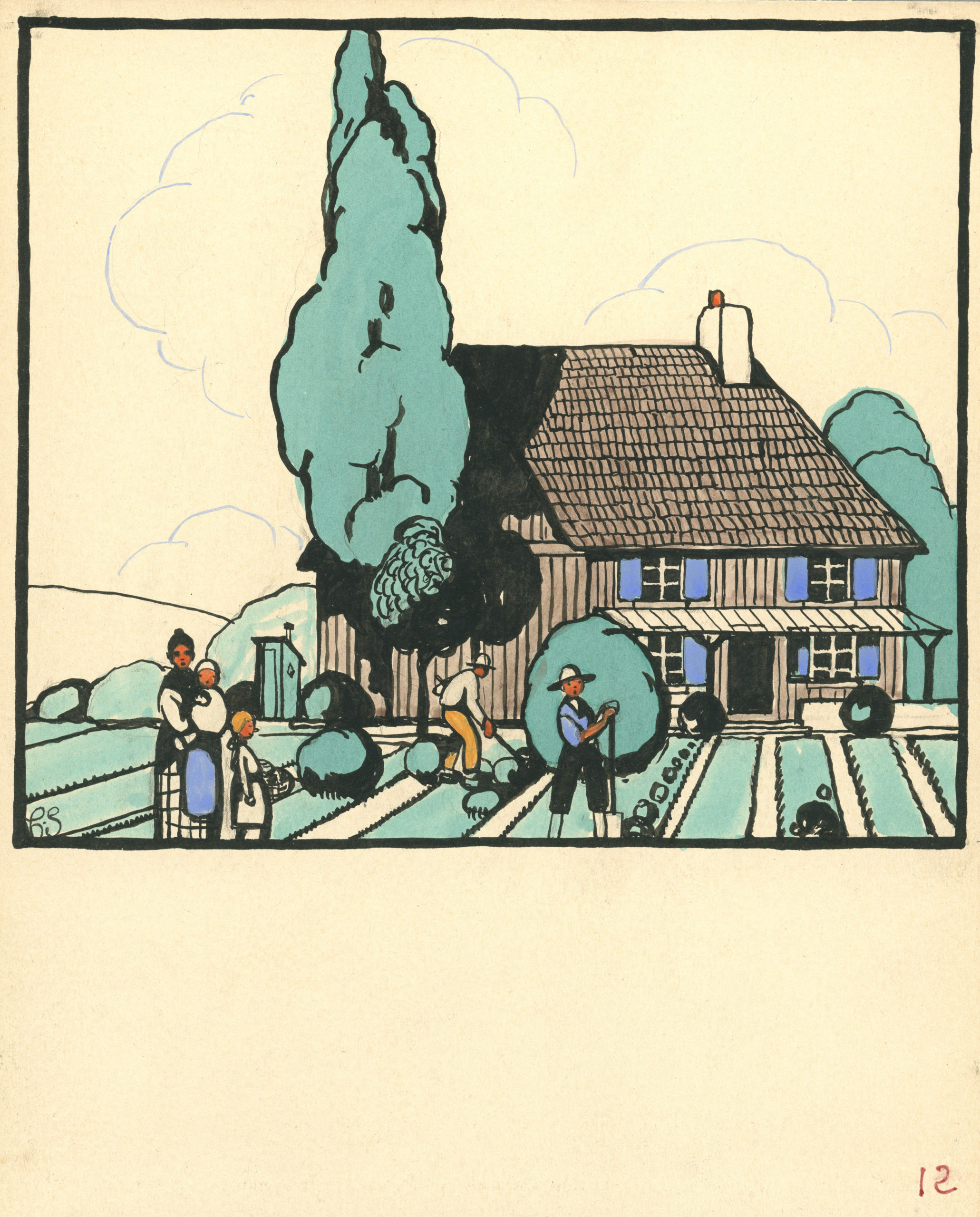

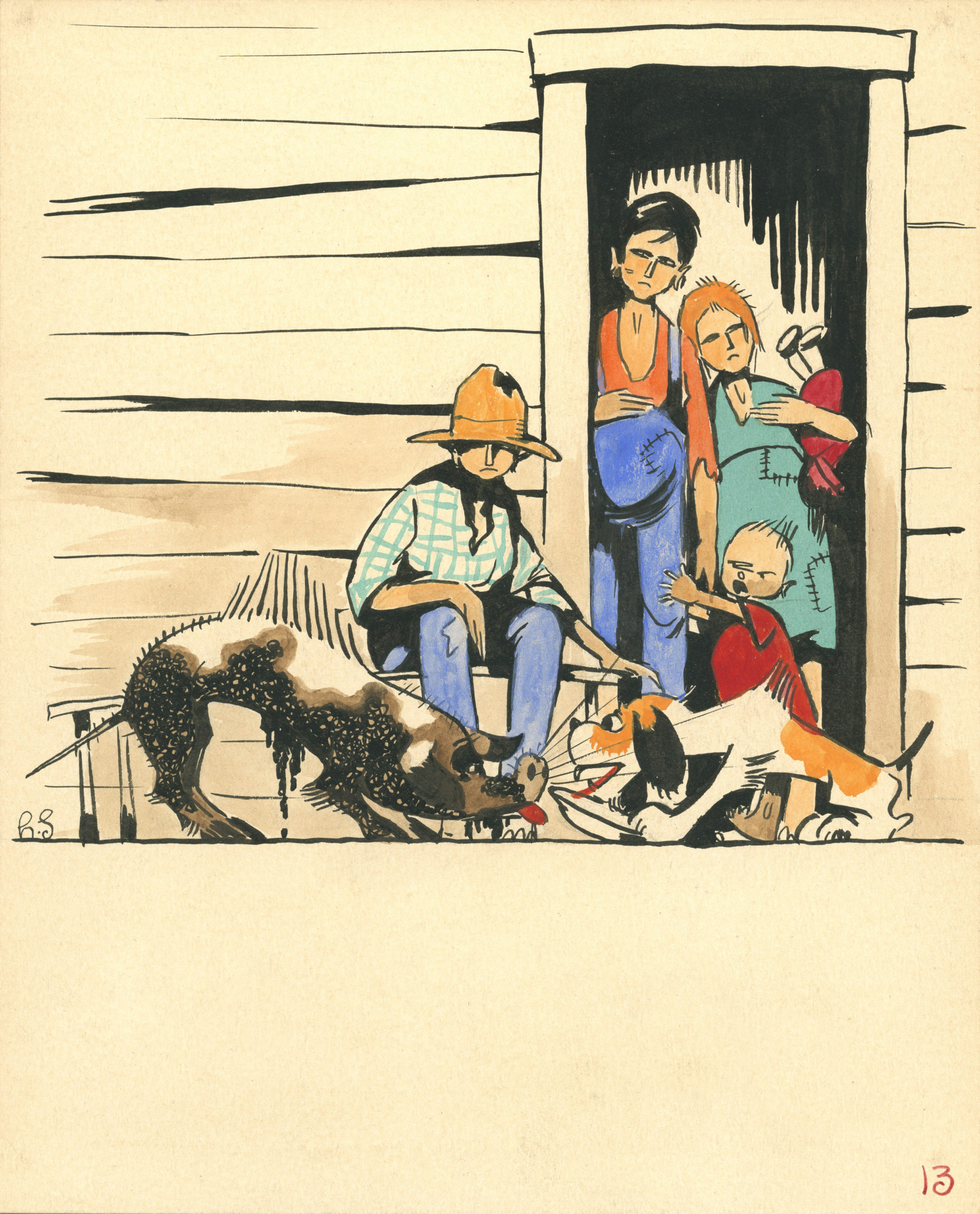

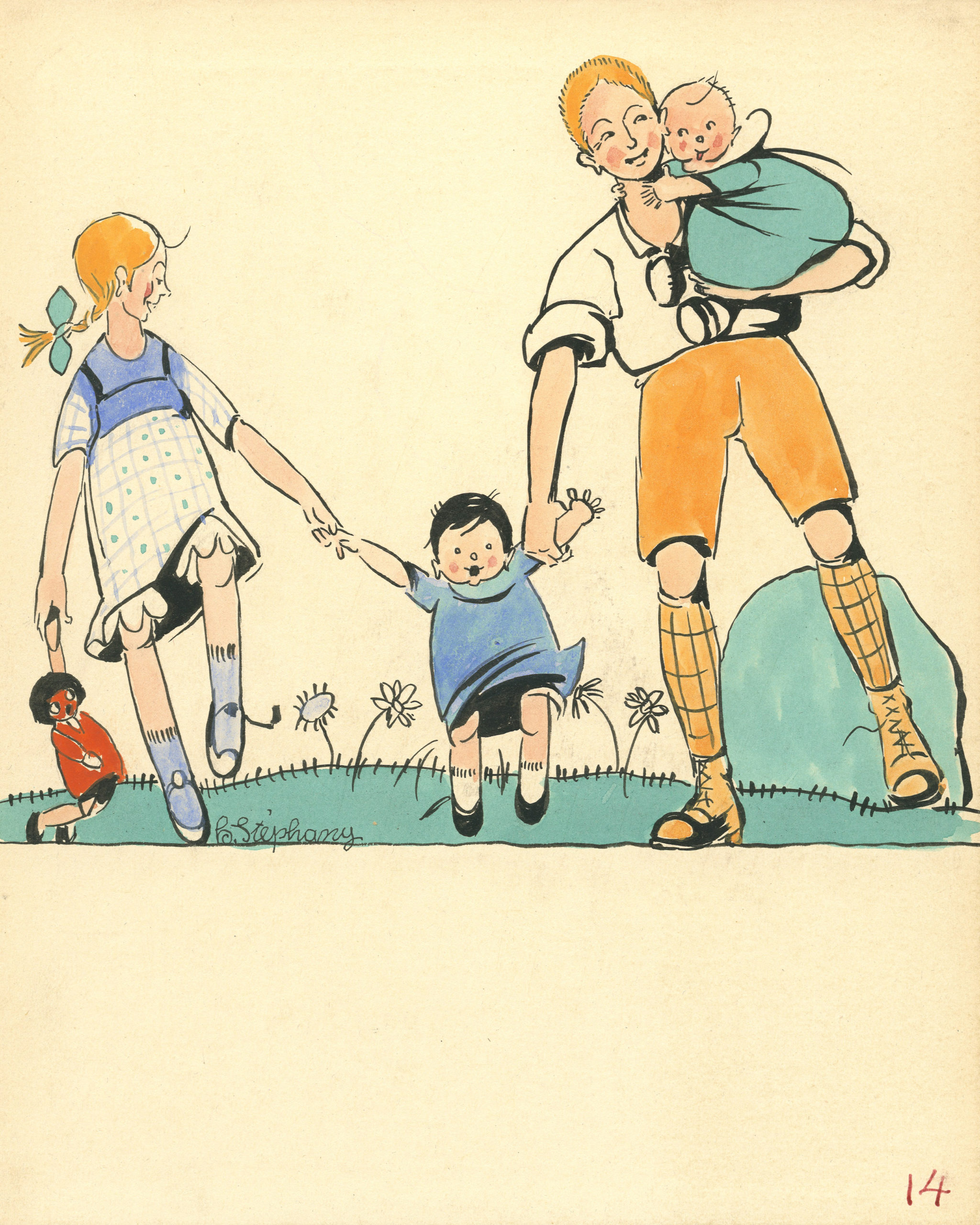

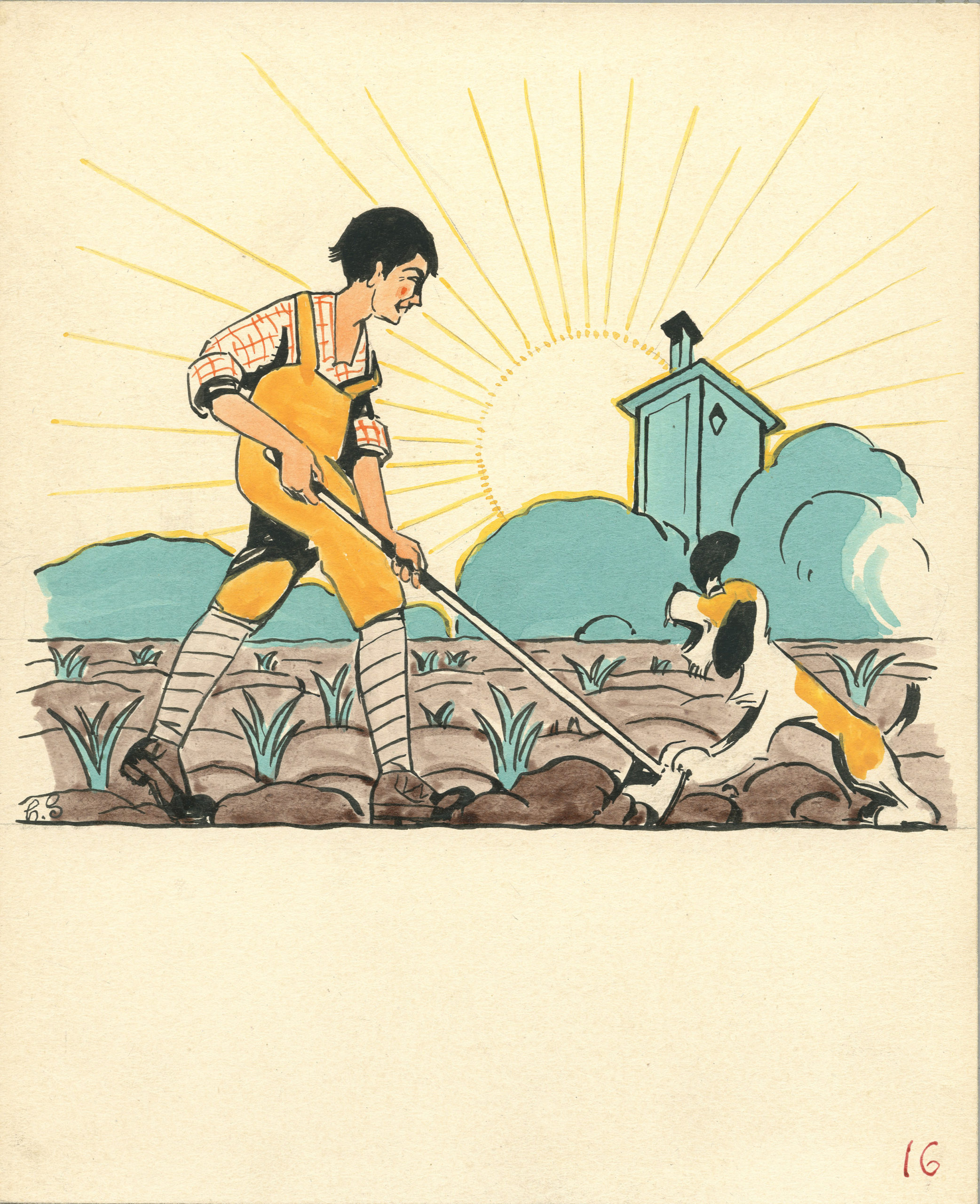

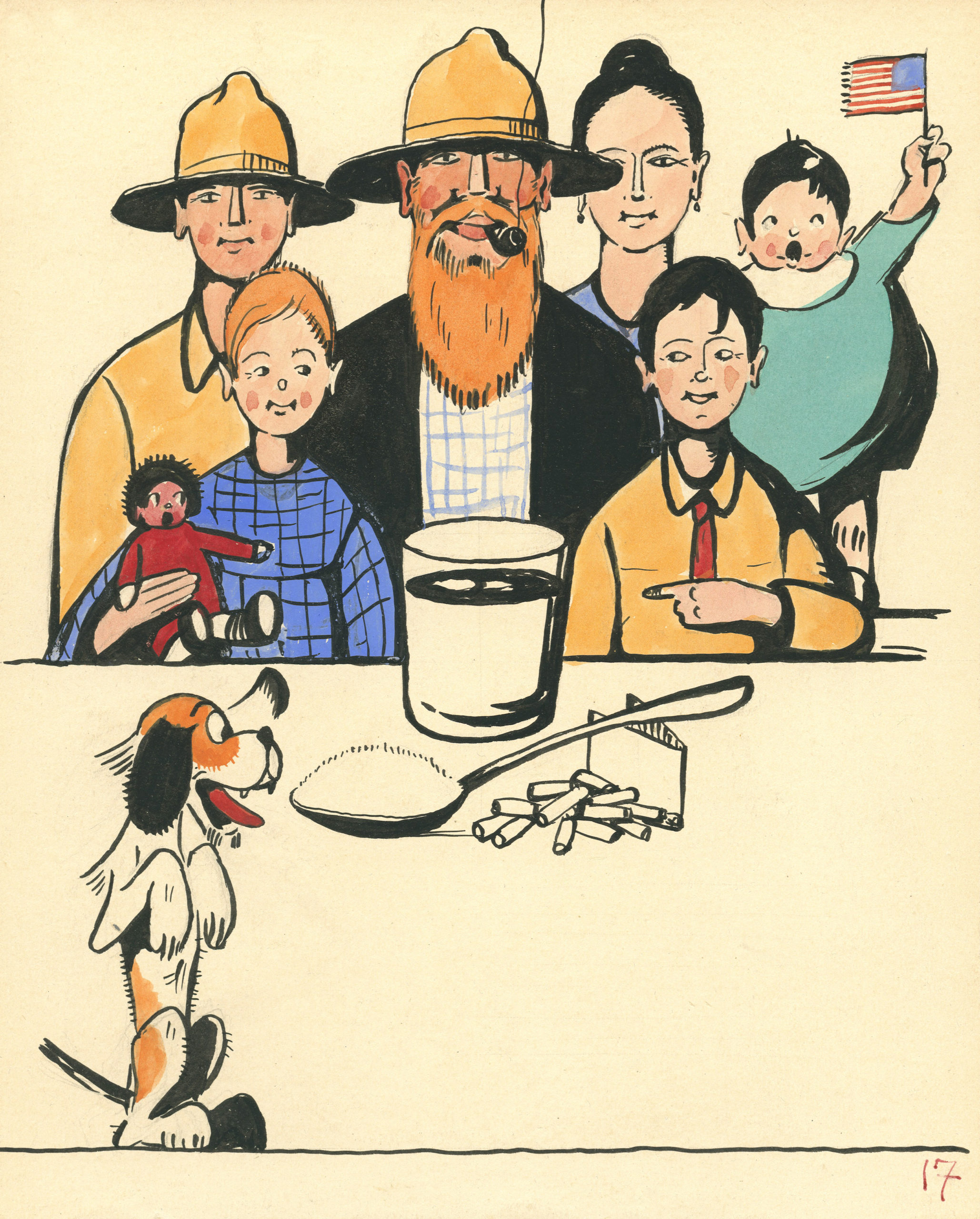

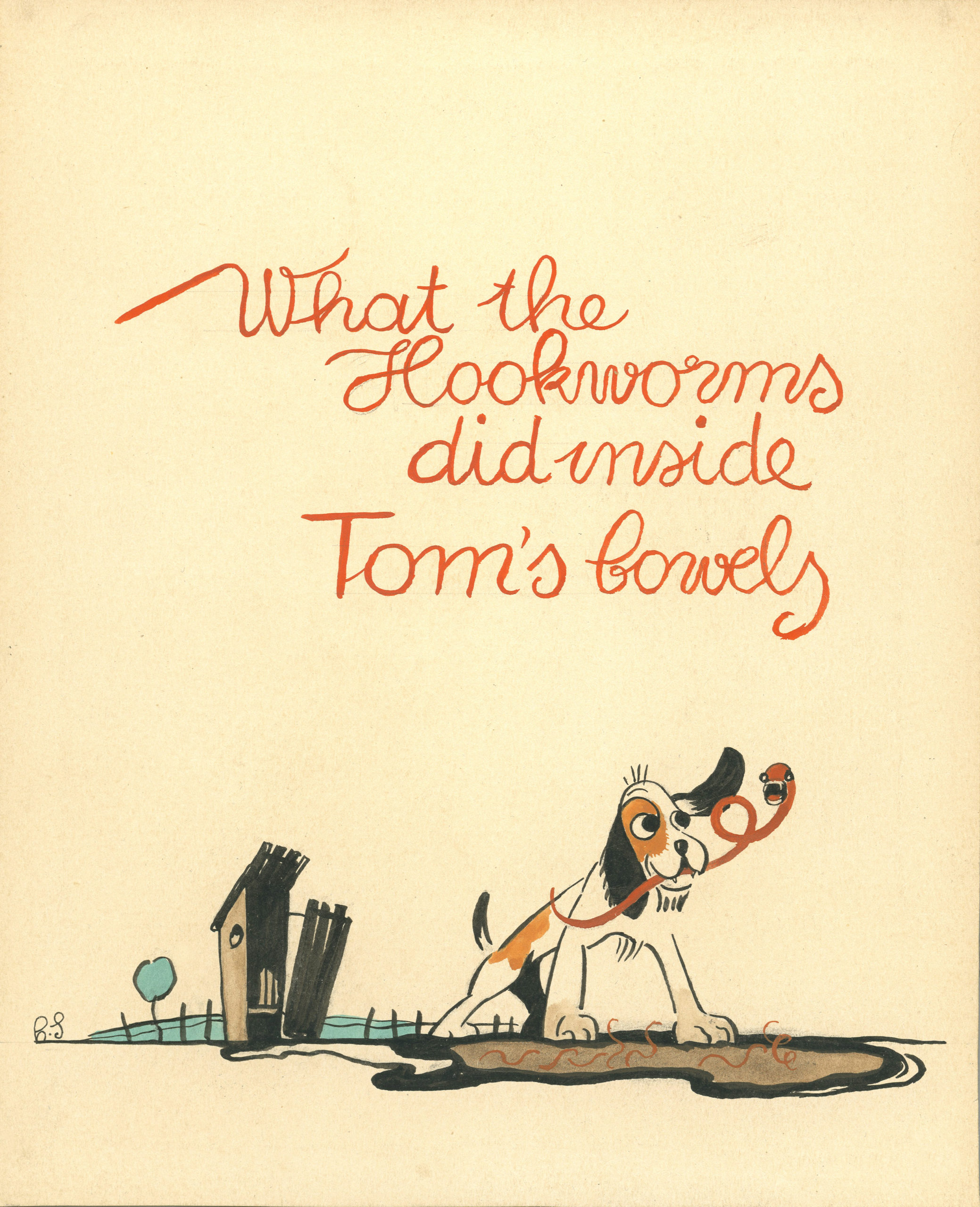

RSC demonstrations were festive, with lantern slides, giant posters, and streamers. In fact, the public lectures were attended less by adults than by children, who enjoyed the slide shows and the chance to look into microscopes. The young people would then bring their new knowledge home. RSC staff handed out brochures and pamphlets. Some were printed later as full-blown children’s books like this one. Photographs, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Gallery: The Story of a Boy, c.1920View this entire archival record online on DIMES

Working at the Local Level

When the RSC began work in 1910, only four out of twelve southern states had a state health board with any legal teeth or even a budget. Work at the county level was even less organized. The RSC aimed to reach people by helping existing agencies grow and become more stable. To that end, it put most of its budget into helping counties hire full-time public health officers.

Like the traveling doctors, these officers were picked for their appeal to locals. In many cases, the RSC paid the health officers’ salaries. It also supplied state-of-the-art equipment like microscopes and paid for workers to operate them. In this way, it contributed to the embedding of a public health system, slowly, piece by piece, in counties across the South. Ettling, 119.

Taking Public Health Global

Rather than achieve permanence on its own, the RSC marked the start of what soon became a more far reaching campaign against hookworm –and a global one. In 1915, Gates decided to move RSC work to the newly launched Rockefeller Foundation, and to add other countries to the roster.

Rose was appointed one of the original trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1913. Then, when the RSC closed, he became Director-General of its International Health Division (IHD) from 1915 to 1923. John Ferrell became Assistant Director-General.The Division’s title was first the International Health Commission, until 1917. It then became the International Health Board until 1927. It did not became the International Health Division until 1927. But because it has become widely known as the IHD, we use that name regardless of date.

A Softer Kind of Peer Pressure

By 1916, the IHD had extended the US work on hookworm disease to 15 foreign countries. It also carried on the RSC work in eight states in the American South.

Rose began to learn more and more from the work abroad. The Rockefeller Foundation’s 1916 annual report relays that he felt “fortunate in encountering a Governmental attitude of great patience in dealing with native populations — an attitude that accomplishes results by persuasion rather than by force.” This backed up what Rose already knew by instinct.Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1916, 55.

While Rose had never been inclined toward the kind of tactics Stiles used, he and his staff were not above using a milder type of peer pressure. In Mississippi, the IHD convinced county newspapers to publish a list of heads of families who had brought their latrines up to the standard approved by the State Board of Health. Each family wished to be recorded on the “honor roll” as early as possible.

In one county, IHD staff took the honor roll concept a step further and posted a large map in a central place showing the location of every home. As each household completed the program, the map was marked to highlight it. As the map became a topic of local conversation, more and more homes completed the work of sanitation. Further delay for the other families became embarrassing.

Spreading the Word

With the larger budget of the Rockefeller Foundation to tap, Rose’s IHD was able to take public relations to a new level. In 1915, it installed an exhibit on hookworm at the Palace of Education at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco. The exhibit had eye catching items like giant wax sculptures of each stage of a hookworm’s life cycle and 3-D models of homes before and after clean-up. There were even plaster body casts from real children showing stunted growth.

The exhibit won a grand prize and proved so popular that organizers doubled its space. Having hired an artist to create the wax sculptures at the Exhibition, the Foundation soon expanded its efforts by using more artists to illustrate educational materials.

Watch: Unhooking the Hookworm, 1920

Assessing Early Public Health

The efforts of the RSC and the continued campaign under the International Health Division changed public health in many ways. But this is not to say that the work was wholly a success. In other countries, for example, the IHD often ran up against pushback when it tried to persuade governments to foot the bill for building latrines.

And data skewed to the hopeful side. Just like the RSC had done before it, the IHD often tallied numbers of “cures” from the number of people who had received medicine. There was rarely follow up on whether patients had in fact taken it.

Moving On to Other Campaigns

As time went on, the Rockefeller Foundation program, under Rose, preferred to focus on outreach and education, and wanted governments to take on the capital costs of the hookworm campaign. For example, building privies and sewage systems. By 1920, the IHD moved away from hookworm, as it began to see that real headway against the disease was too far out of reach for many countries outside the US.

Nevertheless, the basic building blocks of the hookworm campaign transferred to the work on other diseases. These basics included close work with governments. Often, the Rockefeller Foundation would hire public health staff for government offices and pay those staff salaries for a period of time. Also, going back as early as Ferrell’s hookworm memo, making a complete survey of the spread of infection remained a hallmark of the Foundation’s work. And finally, making outreach fun and clear for people on the ground remained central.

Taking Public Health to Scale

Despite the hookworm program’s flaws, its footprint took hold inside the US. While hookworm was not in fact eradicated, the boost that Rockefeller money gave states and counties in the South and across the rural US for building health care systems was real. By 1939, the Foundation had spent over $2.7 million on rural health (an immense amount of money at the time). More than 1,370 counties had full-time health directors, where 30 years earlier there had been a handful at best.Rockefeller Foundation Confidential Trustees’ Bulletin, December 1, 1939, 10-14 Rockefeller Archive Center.

At this point, the Rockefeller Foundation began to pull back from public health work. That’s because, just as Gates and Rose had hoped, the federal government at last stepped in. In 1934, the federal government gave $1 million for rural health units.

Change was in the works. By 1944, the Public Health Service Act would grant the federal government quarantine authority for the first time.

In 1939, the Surgeon General claimed that

“It is due in no small part to the support and encouragement of the Rockefeller Foundation that the whole-time local health service has been established and maintained on a scale sufficient to prove its value.”Ibid.

The real measure of the impact of the Rockefeller funded hookworm campaign is not the ending of hookworm disease (which has yet to happen). Rather, the measure has been the international understanding of the importance of public relations techniques to public health. And in the US, the establishment of public health offices throughout the country with enough professional staff to do the work.

Further Reading

- Elliott M. Reichardt, “The Role of the Rockefeller Foundation in the Origins of Treponematosis Control in Haiti, 1915-1927.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2021.

- Daniel W. Franken, “Hookworm Eradication in Brazil and Beyond.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Stephen Taylor, “Claude Barlow and the International Health Division’s Campaign to Eradicate Bilharzia (Schistosomiasis) in Egypt, 1929-1940.”Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.

- Jacqueline Leckie, “Yaws and Syphilis: Forgotten Diseases of Asia-Pacific.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.Natalia María Gutiérrez Urquijo, “Visiting Nurses and the Rockefeller Foundation in Colombia, 1929-1932.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.

- Maria Catalina Garzon, “Improving Health and Labor Conditions for Coffee Workers: The Role of the Rockefeller Foundation in the Campaigns Against Hookworm in Colombia, 1919 – 1938.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2018.

- Tina Irvine, “Poor, White, and Wormy: Hookworm Eradication in the South and the Boundaries of Whiteness and Citizenship.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2017.

- Jill Briggs, “The Jamaica Hookworm Commission (1918-1920).” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2012.

- Marina Dahlquist, “Unhooking the Hookworm: The Rockefeller Foundation and Mediated Health.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2012.

- Ana Paula Korndörfer, “Fighting Ancylostomiasis (hookworm infection) in Southern Brazil: Cooperation between the Rockefeller Foundation and the Government of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (1919-1923).” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2010.

- Eric B. Thoman, “Historic Hookworm Prevalence Rates and Distribution in the Southeastern United States: Selected Findings of the Rockefeller Sanity Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2009.

- James Burns, “Unhooking the Hookworm: The Making and Uses of a Public Health Film.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2009.

- Frances Gouda, “Discipline versus Gentle Persuasion in Colonial Public Health: The Rockefeller Foundation’s Intensive Rural Hygiene Work in the Netherlands East Indies, 1925-1940.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2009.

- Alexandra Minna Stern, “Tropical Disease Campaigns in Panama: The Entanglement of American Colonial Medicine and Medical Humanitarianism.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2008.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “Rockefeller Sanitary Commission – General,” 1909-1910. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Rockefeller Sanitary Commission – General,” 1911-1916. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – County Health Work,” 1912-1939. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 3.1, International Health Division, Series 908, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Hookworm,” 1950. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 3.1, International Health Division, Series 908, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Hookworm – Reports – Pro Hook-1 – Pro Hook-2,” 1913, 1942. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 3.1, International Health Division, Series 908, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “History,” 1910-1914, 1938-1939. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease records, Administration, Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Stiles, Charles W.,” 1910-1915. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease records, Administration, Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Hookworm – Story of a Boy – Drawings,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, International, Series 100, Hookworm, Subseries 100.H, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Demonstrations,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Alabama, Series 201, Public Health Demonstrations, Subseries 201.J, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Collins and Dawson – Health Survey of Camp Hill, Tallapoosa County,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Alabama, Series 201, Public Health Demonstrations, Subseries 201.J, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Hookworm,” 1912-1914. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Tennessee, Series 248, Hookworm, Subseries 248.H, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Hookworm 2,” 1911-1914. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, North Carolina, Series 236, Hookworm, Subseries 236.I, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Tavistock [Square] Clinic,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, England, Series 401, Medical Sciences, Subseries401.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.