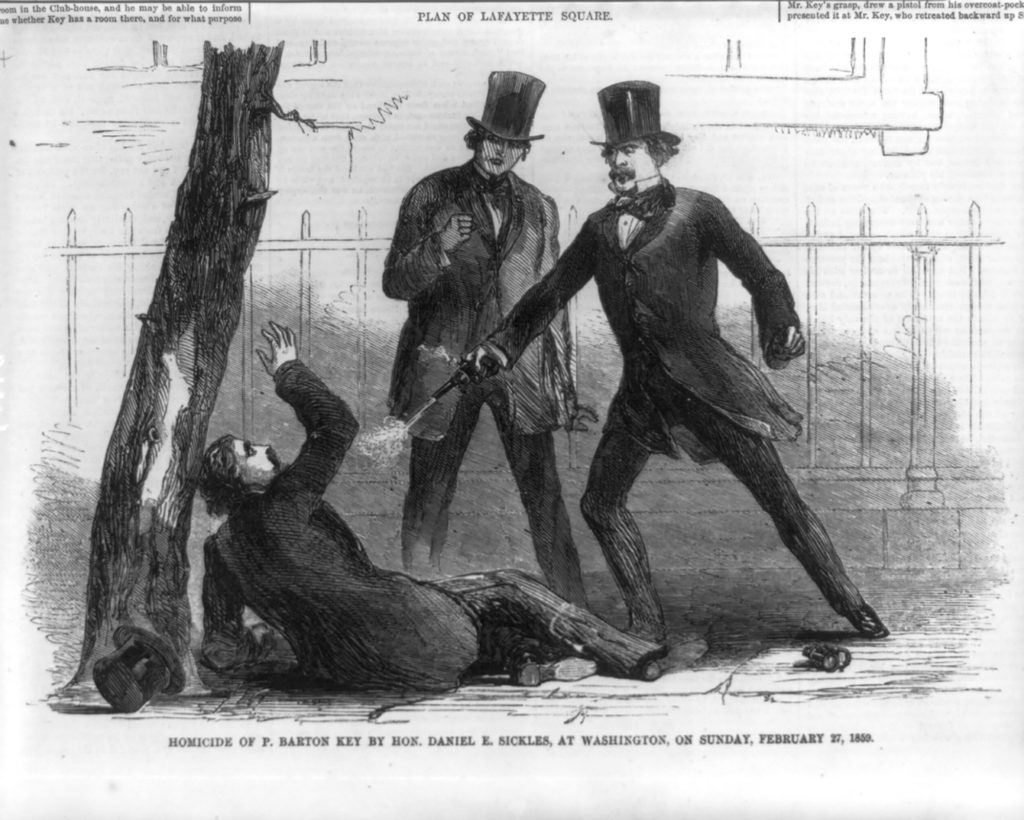

In 1982, the jury in United States v. Hinckley found John W. Hinckley, Jr., the attempted assassin of President Ronald Reagan, not guilty by reason of insanity. Press Release on 2011 Anniversary of the Ronald Reagan Assassination Attempt The verdict shocked the nation and, in response, Congress and state legislatures either abolished the “insanity defense” or significantly tightened regulations for its use.

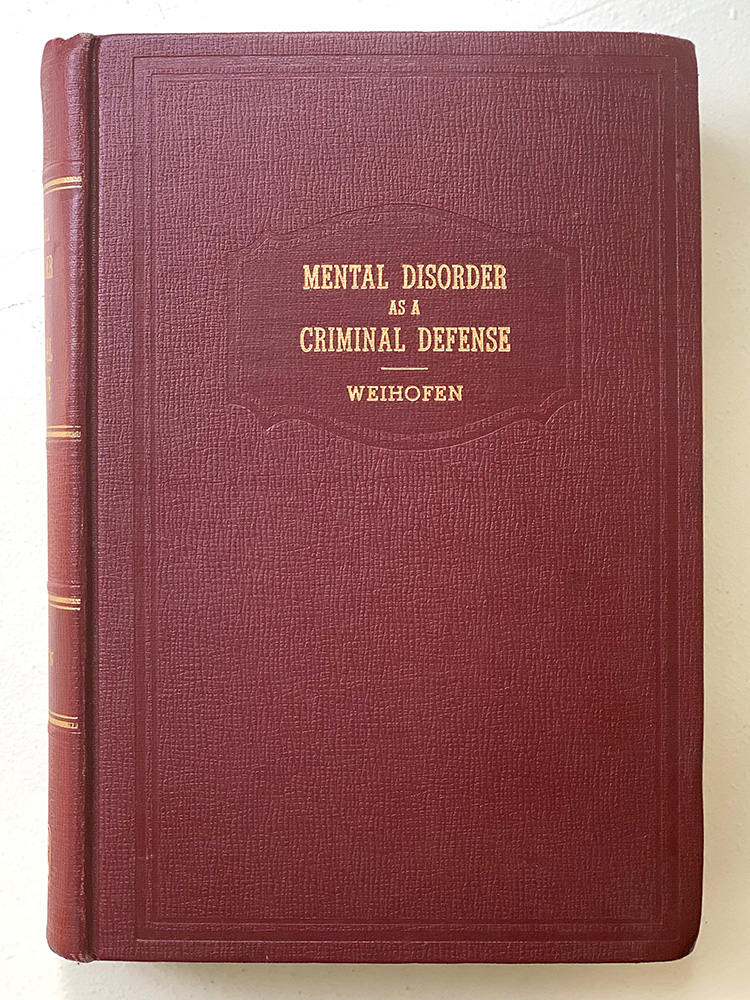

To explain the insanity defense and its origins to the American public, commentators relied on a 1933 text by Henry Weihofen, Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law, and its 1954 re-publication, Mental Disorder as a Criminal Defense.

This publication was a grantee product of the Commonwealth Fund’s Legal Research Committee (LRC), which ran from 1920 to 1943. Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law and its winding origin story illustrate the often unexpected results of grant funding.

Henry Weihofen, Legal Scholar

By the time of the Hinckley case in1982, Weihofen was a senior legal scholar, widely considered an expert on issues of mental illness and criminal law, as well as an advocate for the abolition of the death penalty. The first edition of Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law, published in 1933, had been Weihofen’s first book. Along with the 1954 second edition, it has remained integral to contemporary writing on law and psychiatry, as well as to legal scholarship that addresses the evolution of the insanity defense.Joseph P. Liu, “Federal Jury Instructions and the Consequences of a Successful Insanity Defense,” Columbia Law Review 93, No. 5 (June 1993): 1223-1248. Ralph Slovenko, Psychiatry in Law/Law in Psychiatry (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2009), 2nd edition. Terri M. Couleur, “The Use of Illegally Obtained Evidence to Rebut the Insanity Defense: A New Exception to the Exclusionary Rule,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 74, No. 2 (Summer 1983): 391-427.

Weihofen also published the first textbook on legal writing, Legal Writing Style, now in its third edition and still used in law schools. He concluded his academic career at the University of New Mexico Law School, where his name was given to a chaired professorship.

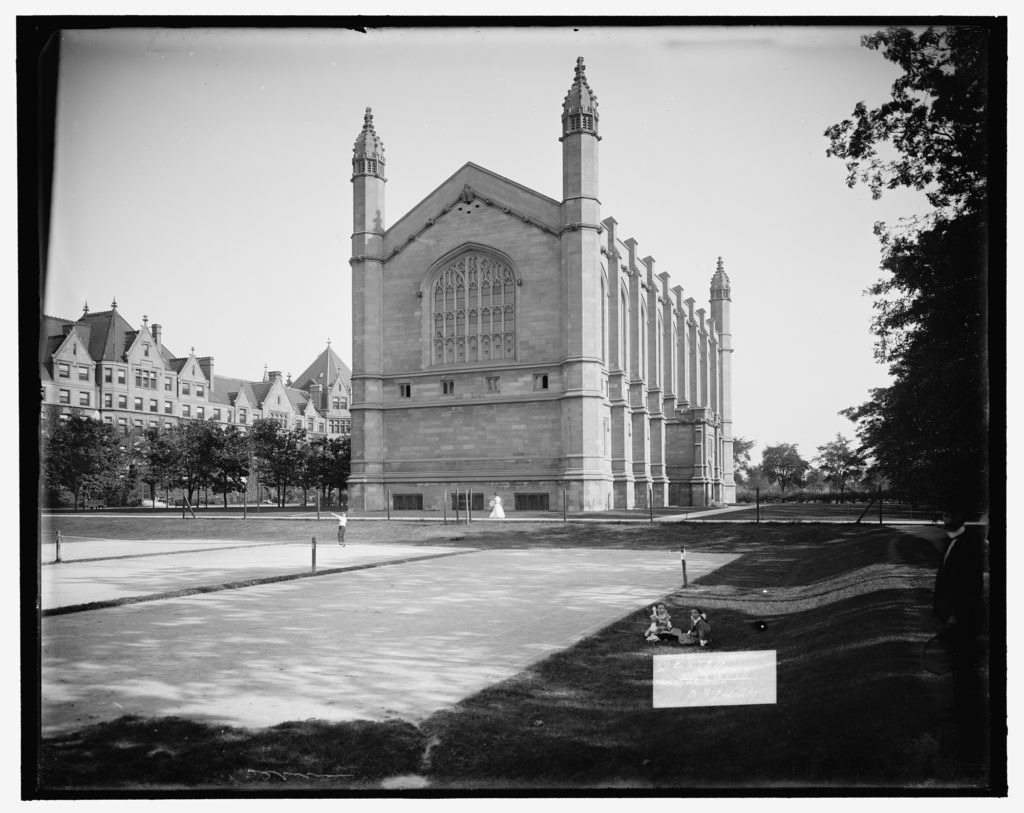

However, when our story begins, the trajectory of Weihofen’s professional life was uncertain. At the time of the LRC grant, Weihofen was merely a graduate student, working as a research assistant for more eminent faculty at the University of Chicago Law School.

A Study of the Insanity Defense

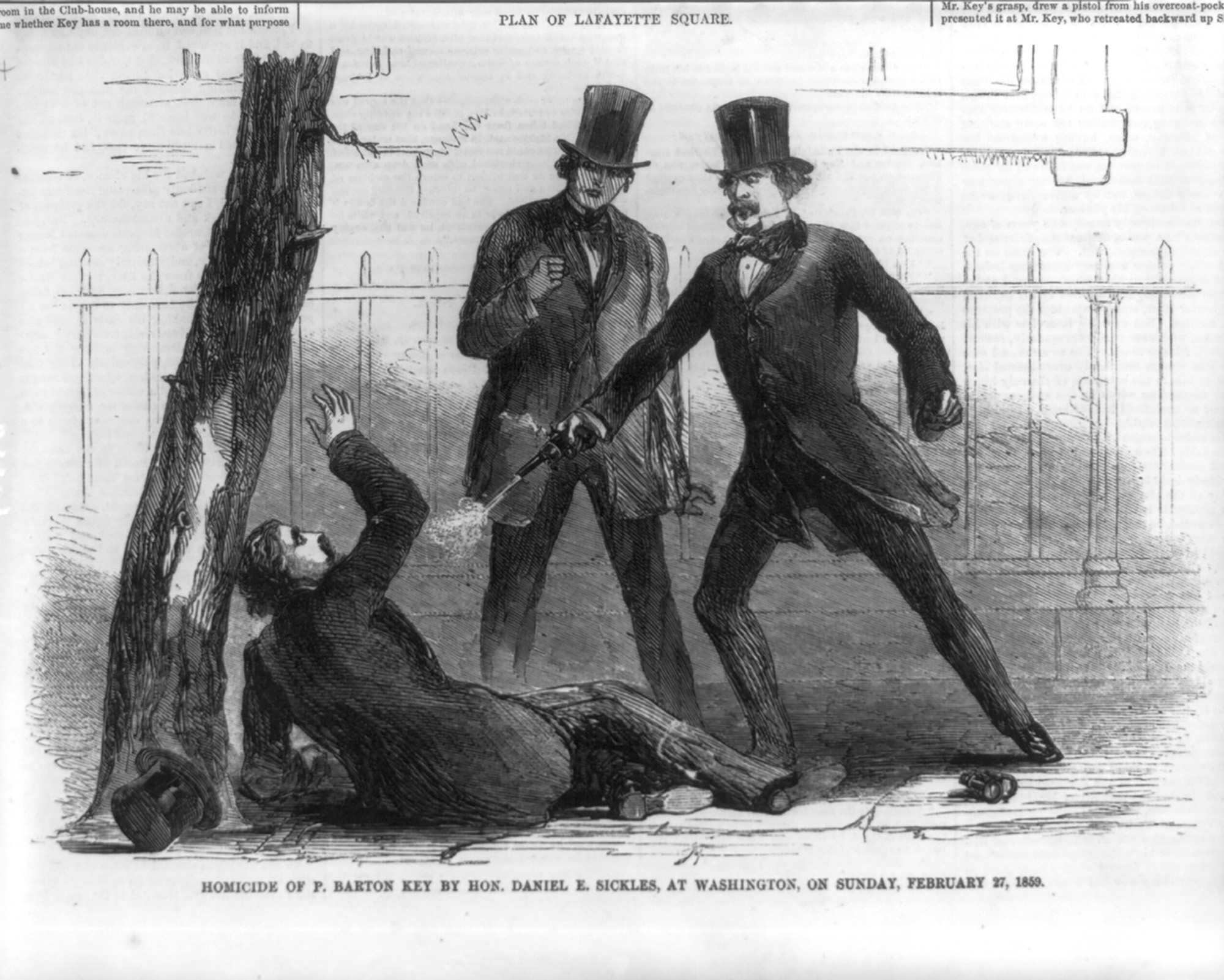

In 1927, the LRC began supporting a University of Chicago Law School study that investigated the history and validity of the insanity defense, even though the study’s subject matter was controversial.

Aside from any specific merits of Chicago’s proposal, it was a project the LRC felt compelled to give the benefit of the doubt, as then-chairman of the LRC, James Parker Hall, was, at the time, Dean of the University of Chicago Law School.Barry C. Smith to George Welwood Murray, “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data),” August 9, 1933, Series 23.2, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In correspondence with the Fund’s director Max Farrand, Harvard Law School Dean and LRC member Roscoe Pound cautioned that productive research in the field of criminal law depended upon the identification of “the right man with the right spirit,” who, if “set to write freely,” might be able to produce substantial work in the field.Roscoe Pound to Max Farrand, “Members’ Correspondence – Roscoe Pound,” July 12, 1921, Series 23.1, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.However, Pound was concerned that this study had high human stakes and that without sufficient LRC oversight, a university or institution might appoint someone who was not sufficiently qualified to take on such an important research task.

For the University of Chicago Law School’s project on “The Insanity Defense in Criminal Law,” Pound’s worry would prove prophetic.

The Student Becomes the Teacher

The Chicago study was to be conducted under the direction of senior legal faculty, with $5,000 of compensation awarded beginning in 1928 to support research or clerical help.“Minutes of the Meeting of the Legal Research Committee,” December 3, 1927, Series 23.1, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Barry C. Smith to James P. Hall, “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data),” December 21, 1927, Series 23.2, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.Consequently, in the list of expenditures the Law School provided to the Fund, only one expense was mentioned with regularity: the salary of a research assistant, identified as “H. Weihofen.”

However, by the time the new Fund Director Barry C. Smith, who succeeded Farrand in 1928, reached out to the University of Chicago in September 1929, it was revealed that the project had veered in an unexpected direction.

Getting Ahead of Himself?

By September 1929, the status of the research assistant, Henry Weihofen, had been elevated to lead researcher and author of the entire LRC insanity defense research grant — all while Weihofen was still a graduate student.“Summary of Expenditures, Commonwealth Fund: Investigation of Legal Tests of Insanity,” July 1, 1928 to September 30, 1928, Series 23.2, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center. “Summary of Expenditures, Commonwealth Fund: Investigation of Legal Tests of Insanity,” October 1, 1928 to December 31, 1928, Series 23.2, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Henry Weihofen to Barry C. Smith, “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data),” September 16, 1929, Series 23.2, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

To Smith’s surprise and dismay, LRC funding had not been used for high-level scholarship intended to impact legislation, but rather as funding for a graduate thesis. In fact, Weihofen would later receive a JSD from the Law School as a direct result of his thesis work. Harry A. Bigelow to Barry C. Smith, “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data),” November 17, 1930, Series 23.2, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Barry C. Smith to Harry A. Bigelow, “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data),” October 6, 1933, Series 23.2, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

A Groundbreaking Publication

The transformation of the LRC University of Chicago Law School grant into seed money for a graduate thesis was disappointing indeed to the Fund and to the LRC. The LRC’s advisors cautioned that such a shift in outcome should be avoided in the future. Reflecting on the incident, LRC Chairman George Welwood Murray wrote:

“…if the matter were up now I should advise the Committee that one of the main questions involved in our decision would be the personality of the individual requested to take up the investigation and exposition. I should not advise that it be left to any faculty anywhere to designate a gentleman who would do the work simply toward his doctorate.”George Welwood Murray to Geddes Smith, “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data),” August 5, 1933, Series 23.2, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Yet, despite everything, the Fund honored its original grant commitment, and provided support for the publication of what had become, at this point, Weihofen’s personal study, provisionally entitled Legal Tests of Insanity.George Welwood Murray to Barry C. Smith, “Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law,” June 15, 1931, Series 13.9, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.By the time of publication in 1933, the study had become what is now known as Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law–the text that launched the career of a distinguished legal scholar, and the text that, with its 1954 revised edition

(now entitled Mental Disorder as a Criminal Defense), remains a touch point for insanity defense studies to this day.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data)“, 1922-1923, Commonwealth Fund records, Program Files, Legal Research Program, Subgroup 1, Series 23, Legal Research Projects, Subseries 2, Administrative Law and Practice, Subseries 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data)“, 1927-1931, Commonwealth Fund records, Program Files, Legal Research Program, Subgroup 1, Series 23, Legal Research Projects, Subseries 2, Administrative Law and Practice, Subseries 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of Chicago Law School – Insanity as a Defense in Criminal Law (Correspondence and Financial Data)“, 1931-1933, Commonwealth Fund records, Program Files, Legal Research Program, Subgroup 1, Series 23, Legal Research Projects, Subseries 2, Administrative Law and Practice, Subseries 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Karpman Study of the Criminally Insane“, 1929-1930, Bureau of Social Hygiene records, Projects, Series 3, Criminology, Subseries 3_4, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Related

The Commonwealth Fund Brings Hospice Care to America

Care for the dying, not care for a cure, was a new idea in the 1970s.

The Long Road to the Yellow Fever Vaccine

The yellow fever vaccine developed in the 1930s has been used worldwide ever since. Creating it took years and cost several lives. Some thought it would never happen.

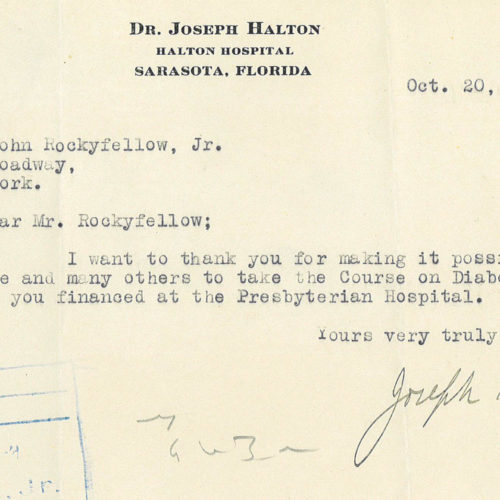

The “Insulin Gift”

In 1923, a wealthy philanthropist’s funding helped make life-saving treatment for diabetes available to patients and doctors.

Photo Essay: The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission and the American South

Battling hookworm on rural farms laid the groundwork for a global public health system.