The 1970s Employment Crisis

In the 1970s and 1980s, officers in the Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity program sought to address unemployment in what they called “minority” communities. These efforts aligned with the program’s broader goal: to secure and expand social, educational, and economic opportunities for people of color in the United States. As the country’s urban crisis worsened in the 1970s, Equal Opportunity program officers tried to well as support public policies designed to address youth unemployment in marginalized communities, as well as clarify the causes of that unemployment.

These foundation officers began by commissioning a background paper on the problem of youth employment. Authored by political economist Lester Thurow, of MIT’s Sloan School of Management, the paper became the basis of a conference on “Unemployment of Youth and Policy Alternatives,” held at the Rockefeller Foundation in May 1977. Discussants included Rockefeller Foundation Social Sciences Director Bernard E. Anderson, United States Secretary of Labor John Dunlop, labor economist Beatrice Reubens, and economist James Tobin.

The Foundation funded extensive research into the problem in the late 1970s.

Despite these efforts, youth employment never emerged as a full-fledged Rockefeller Foundation program. By 1980, Foundation staff and trustees had reevaluated the organization’s focus under a new president and in that process, recognized that the structural issues facing communities of color extended well beyond the single issue of youth employment.

This reevaluation may have also resulted from pragmatic concerns. In the late 1970’s, the field of youth employment was saturated with programs developed by the federal government, several foundations, and various local public and private agencies. Then, Ronald Reagan’s election as US President in 1980 made foundations more skeptical about the federal government’s willingness to replicate and enlarge their programs, or even continue its own existing services. The “Reagan Revolution,” in which federal programs were significantly cut back, posited that government-supported social programs were the problem, not the solution, and urged the non-profit sector to take up the slack.

Responding to the Reagan Revolution with a New Foundation Focus

In a time of great anxiety throughout the foundation world and the non-profit sector, this political shift forced the Rockefeller Foundation to reframe its focus on both communities of color and jobs. In 1981, President Reagan signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA), which “encouraged states to devise experimental ‘demonstration projects’ designed to get welfare recipients to work.”Judith Sealander, The Failed Century of the Child: Governing America’s Young in the Twentieth Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 123.

What OBRA meant on the ground was that Americans on public assistance feared for their livelihoods, and the non-profit social services sector struggled to keep up with the sudden enlargement of its role. Famously, Reagan introduced the mythical character of the “welfare queen” into public consciousness and popular culture. His supporters charged that the federal social programs that had been in place since the 1960s fueled inflation and made a prosperous US economy impossible, castigating individuals for not paying their own way. His critics charged that his plans for the US economy were built on the backs of the poor, cutting government aid in favor of the defense budget and tax breaks for the wealthy.

Responding to the tenor of the times, Rockefeller Foundation leadership and social sciences staff decided to implement their own demonstration project aimed at improving the circumstances of women of color receiving public assistance. It invested $17.5 million dollars (nearly $30 million today) in the Minority Female Single Parent (MFSP) demonstration, which ran between 1982 and 1988. Although the Foundation seemed to work within the federal framework, its officers approached the problem with a different ideological perspective than the Reagan administration. In a 1981 New York Times article, RF President Richard Lyman said that through the MFSP,

We want to underscore the foundation’s commitment to poor [B]lacks and Hispanics at a time when their plight ranks relatively low on the national agenda.

New York Times, December 20, 1981.

Community Partners

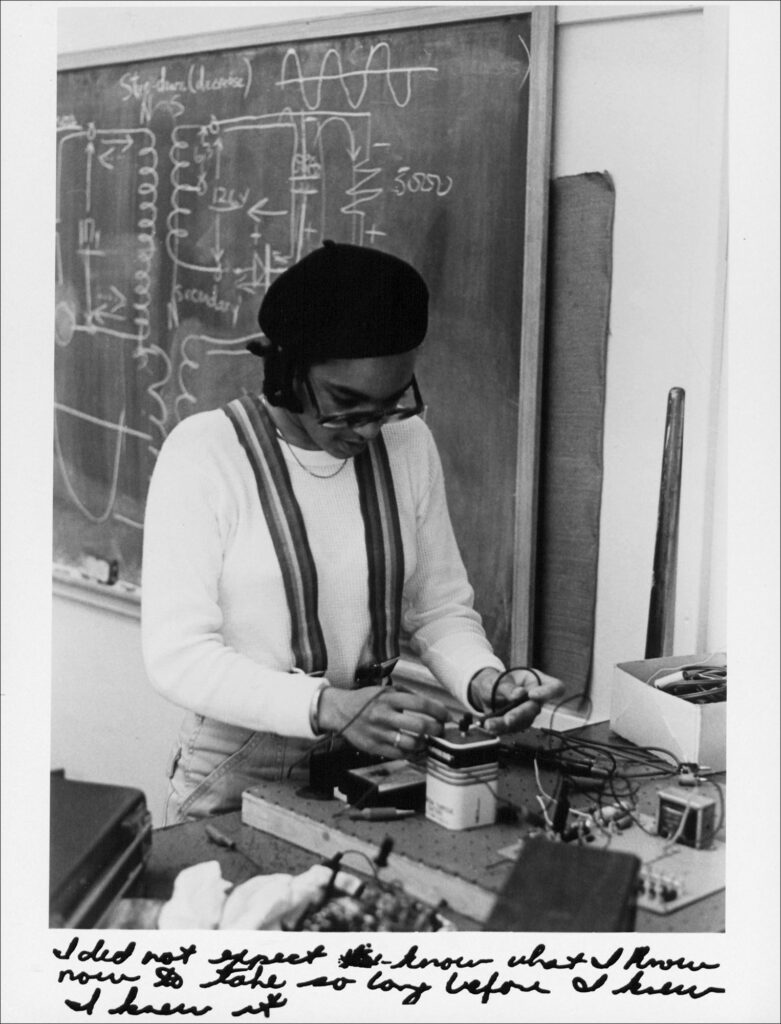

The MFSP demonstration sought to examine whether community-based organizations could run employment training and counseling programs that would reduce low-income single mothers’ reliance on public assistance. The Rockefeller Foundation partially funded four community-based organizations to operate pilot programs: the Atlanta Urban League, Opportunities Industrialization Center in Providence, Rhode Island, the Center for Employment Training in San Jose, California, and Wider Opportunities for Women in Washington, D.C.

To address the employment challenges facing low-income single mothers, each organization designed the details of its own program. Nearly 4,000 women enrolled in these demonstrations, which offered a variety of services, including job skills assessments, counseling, education, child care assistance, job-skills training, and job placement assistance.

“Day-to-Day Concerns Were Not Addressed”: Why the Program Failed

In 1987, the Foundation issued an interim report on the factors they identified as hindering the success — or causing the outright failure — of these job training pilot programs. The report’s title, “From Welfare to Work,” echoed the political climate of the 1980s. Its authors wrote,

The Foundation is publishing these interim observations in the hope that policymakers and others responsible for such programs in the future can build on the lessons of the past.

“From Welfare to Work,” 1987“From Welfare to Work: Minority Female Single Parent Program,” 1987, Rockefeller Foundation Collection, RG 1.23, Series 200, Box R3062, Folder “Employment Program for Minority Group Female Single Parents, 1992-1994,” Rockefeller Archive Center.

Lacking Support Services: Childcare, Language, and Job Placement

“From Welfare to Work” identified a number of reasons for the MFSP program’s failure to place participating women into paid jobs.

First, the report’s authors noted that childcare was essential for participants to take full advantage of the training offered, but was supplied by only one of the four centers. Second, although Foundation staff had highlighted poor reading and language skills as a significant problem for the population they aimed to serve, general literacy classes were as far as most of the training programs went. Literacy training needed to be made relevant to a job for participants to relate well to it, yet was not framed in this way. Third, the structure of the programs should have focused not only on job training, but also on job placement, yet did not do so in any systematic way. And finally, the women needed access to support services — personal counseling, transportation, medical care, family planning services, legal services, and housing — to help them succeed in the program.

As the training organizations themselves reported, “if a participant’s day-to-day concerns were not addressed, sooner or later, she will drop out.”“From Welfare to Work: Minority Female Single Parent Program,” 1987, Rockefeller Foundation Collection, RG 1.23, Series 200, Box R3062, Folder “Employment Program for Minority Group Female Single Parents, 1992-1994,” Rockefeller Archive Center.The program’s final evaluation supported these early conclusions, and added a few more: above all, “immediate, job-specific training with a strong focus on getting trainees into jobs” proved more successful than providing education first.Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., Evaluation of the Minority Female Single Parent Demonstration, Volume I, Summary Report, October 1992, xiii.

…if a participant’s day-to-day concerns were not addressed, sooner or later, she will drop out.

“From Welfare to Work,” 1987

Only one of the four programs, run by the Center for Employment Training in San Jose, California, resulted in long-term earnings gains. Perhaps not surprisingly, this was the only center that offered child care arrangements during the training. But even further, this program differed from the others in that it provided job-specific skill training up front (based on jobs that existed in the local area), and wove literacy and math skills into the training.

The other three programs led with basic education, failing to connect it to the work that participants might seek. The San Jose center’s approach to training focused not only on developing skills required for specific jobs, but also on training in areas known to have large labor needs. Because of this, the program could work to place participants in a wider array of jobs immediately after training.

A “Constructive and Important Failure”

In the end, the MFSP program achieved very minimal success, even by its own measures. Within the Rockefeller Foundation, the program’s failures prompted a major debate about whether the Equal Opportunity program should concentrate its resources on research and policy recommendations instead of action-oriented demonstration projects.

To a certain extent, Rockefeller Foundation leaders considered this an institution-wide question in the 1980s. In a July 1984 memo to Foundation President Richard Lyman about the future direction of the Rockefeller Foundation, one staffer noted,

I am struck with the persistent ambivalence at the RF over whether our mission can or should be to help solve problems or merely to diagnose their causes and suggest alternative ways for solving them.

John StremlauJohn Stremlau to Richard W. Lyman, July 16, 1984, Rockefeller Foundation Collection, Richard Lyman Papers, Box 1, Folder 5, RAC.

In the end, the MFSP demonstration tried to reconcile the tension between research and action by developing a method with applicability to other anti-poverty programs. For this reason, studying where the MFSP program fell short held important practical potential.

Many of its lessons were clear: the program had not listened to the needs of its real stakeholders: the parents it intended to serve. Neither had it questioned the desirability of moving low-income mothers quickly “from welfare to work” without the appropriate supports in place to render a job a net gain in these mothers’ lives.

Some outside commentators agreed. Historian of philanthropy Peter Frumkin, for instance, called the MFSP program “one of philanthropy’s most constructive and important failures” — and, he said, “constructive failures create value by helping us understand what went wrong.”Peter Frumkin, Strategic Giving: The Art and Science of Philanthropy (Chicago: The University of Chicago, 2006), 68.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “Program and Policy – Youth Employment,” 1976-1978. Rockefeller Foundation Records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 3.2, Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “EMPLOYMENT PROGRAM FOR MINORITY-GROUP – FEMALE SINGLE PARENTS,” 1981-1994. Rockefeller Foundation Records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.23, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Employment Program for Minority Group Female Single Parents – Supplementary Material – ABT Chronological Files,” 1982-1985, 1981-1994. Rockefeller Foundation Records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.24, United States, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Reports – The Minority Female Single Parent Demonstration: Program Costs and Operations,” 1988, Richard W. Lyman Papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Studies on the impact of the 1981 Omnibus Reconciliation Act on working welfare women,” 1983-1984, Ford Foundation Records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 11775-13948, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Opinion Research Center – Youth Unemployment,” Rockefeller Foundation Records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.3-SG 1.8 (A-76-A82), Projects (A81), Subgroup 7, United States, Series 200, Social Sciences, Subseries S, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.