In 1923, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Canadian physicians Frederick G. Banting and John J.R. Macleod for the discovery of insulin.

Insulin today is widely used to treat diabetes, a disease in which a body cannot adequately process blood glucose, leading to high blood sugar levels. Before insulin treatment, diabetes was a truly life-threatening and often fatal disease. Previous attempts at medical intervention for diabetics were unsuccessful, to say the least, and often involved extreme starvation diets. Insulin was therefore quite literally a life-changer for diabetic sufferers.Jeffrey Friedman, “Discovery Interrupted: How World War I Delayed a Treatment for Diabetes and Derailed One Man’s Chance at Immortality,” Harper’s Magazine, November 2018, 45.

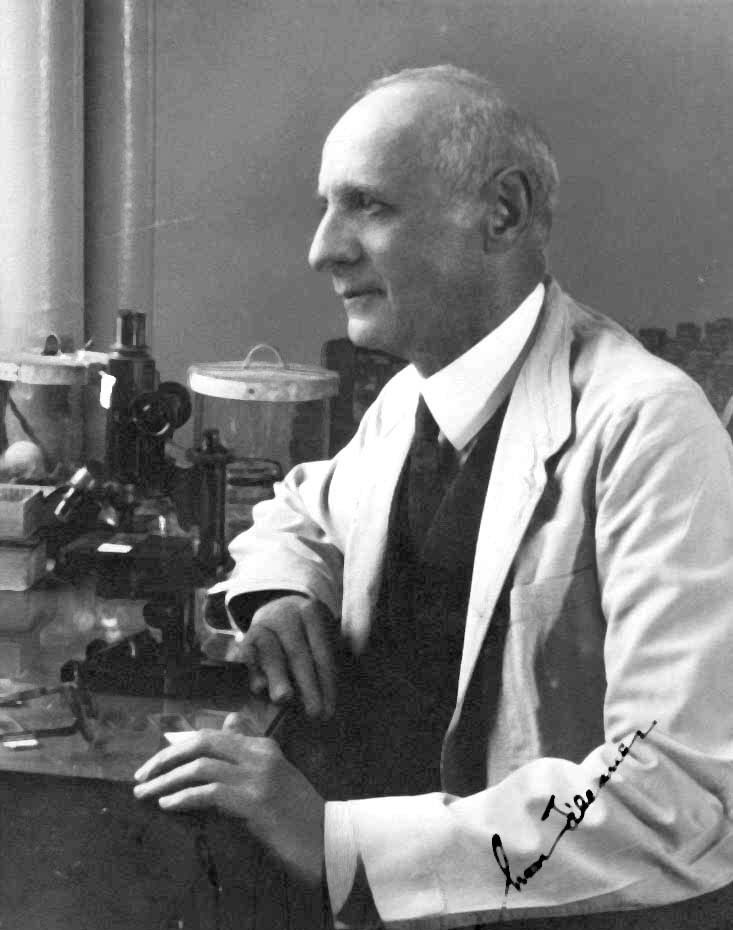

Banting and Macleod’s work was based on the initial discoveries of

Israel Kleiner, a biochemist at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (now Rockefeller University).

The disruptions caused by World War I had prevented Kleiner from moving forward with his finding that an exclusively pancreatic hormone regulates blood glucose. In studies conducted from 1914-1919, Kleiner established that a failure of the pancreas causes diabetes and that pancreatic extracts could neutralize glucose in the blood of diabetic animals. Banting, Macleod, and their team then expanded upon Kleiner’s work to develop insulin treatment for human patients in 1922. Friedman, “Discovery Interrupted.”

In 1923, the same year that Macleod and Banting received the Nobel Prize, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (JDR, Jr.) stepped forward to join with the Rockefeller Institute in ensuring the rapid application of this scientific breakthrough.

It began when Dr. Simon Flexner, director of the Rockefeller Institute, wrote to one of JDR, Jr.’s advisers to suggest that a gift of funds would enable the insulin work to “arrive more quickly and perfectly at practical results than would be the case probably if the study is allowed to take its own unaided course.” Simon Flexner to Arthur Woods, March 28, 1923, Series III 20, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Around the same time, JDR, Jr.’s office received an anonymous letter addressed to the philanthropist. The letter’s author described how his child’s life had been saved by the new diabetic insulin treatment, and pleaded with JDR, Jr. to help make this treatment more widely available so others could survive the otherwise deadly condition.Arthur Woods to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., April 18, 1923, Series III 20, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Moved by the man’s pleas, JDR, Jr.’s associates proposed to Flexner the idea for insulin distribution coupled with physician training for administering the doses. On April 18, 1923, these associates and Flexner together urged JDR, Jr. to underwrite the project.Woods to Rockefeller, April 18, 1923.

JDR, Jr.’s interest was heightened by an even more personal connection. His father’s longtime philanthropic adviser, the Rev. Frederick T. Gates, and Gates’s wife were both diabetics.

On April 28, 1923, Gates wrote directly to JDR, Jr., describing insulin treatment as “simply magical.” On the treatment, he asserted, he and his wife were both experiencing renewed “strength, life and cheer.”Frederick T. Gates to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., April 28, 1923, Series III 20, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Gates pointed out, however, that effective mass distribution would cost between $100,000 – $150,000 (more than $1.5 million in 2019 dollars).Frederick T. Gates to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., April 28, 1923.

Gates explained that the kind of insulin treatment he had received remained limited to a select few hospitals, with “thousands of people in younger life,” whose survival depended on insulin, lacking any access to those hospitals.

Gates exhorted JDR, Jr. to personally take up this cause because

…this is the greatest philanthropic plum of the generation ready to fall into your hands, and I want you to have the benefit of it.

Frederick T. Gates to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., April 28, 1923.

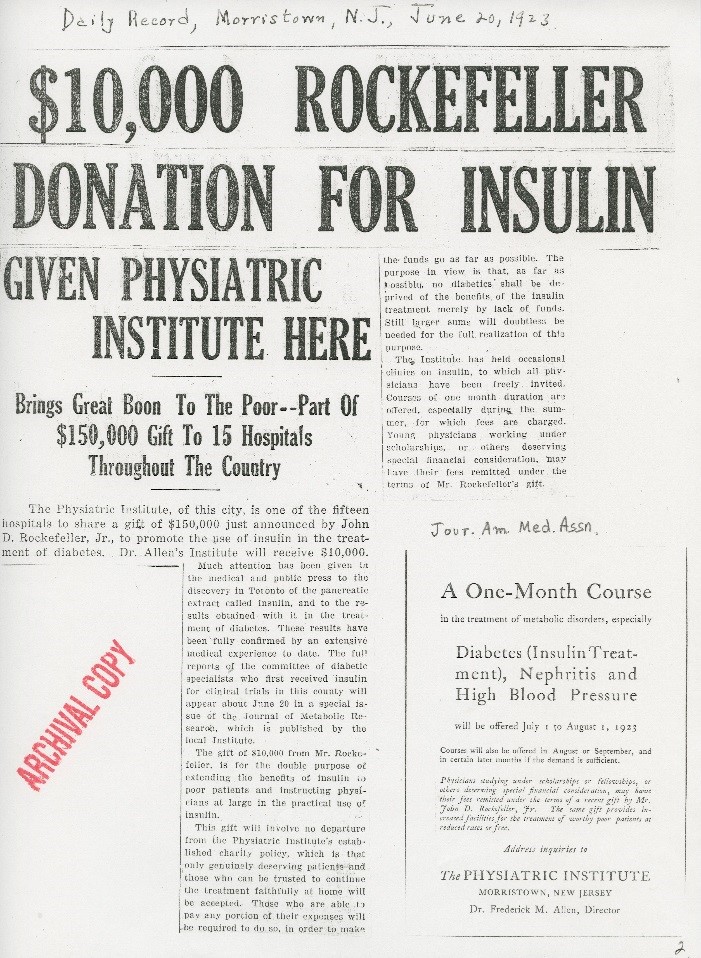

On May 2, 1923, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. pledged $150,000 toward the distribution of insulin to hospitals in the United States and Canada.A.L. Boulware to Simon Flexner, May 14, 1923, Series III 20, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

He later increased his pledge by an additional $50,000 to further the effort.John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to Simon Flexner, June 19, 1923, Series III 20, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Institute selected the hospitals and administered the gift.Moran-Thomas, Amy, “In Search of the ‘Philanthropic Plum’: Diabetes Research, Hookworm Interventions, and Comparative Philanthropy in Historical Perspective,” IssueLab, January 1, 2010.

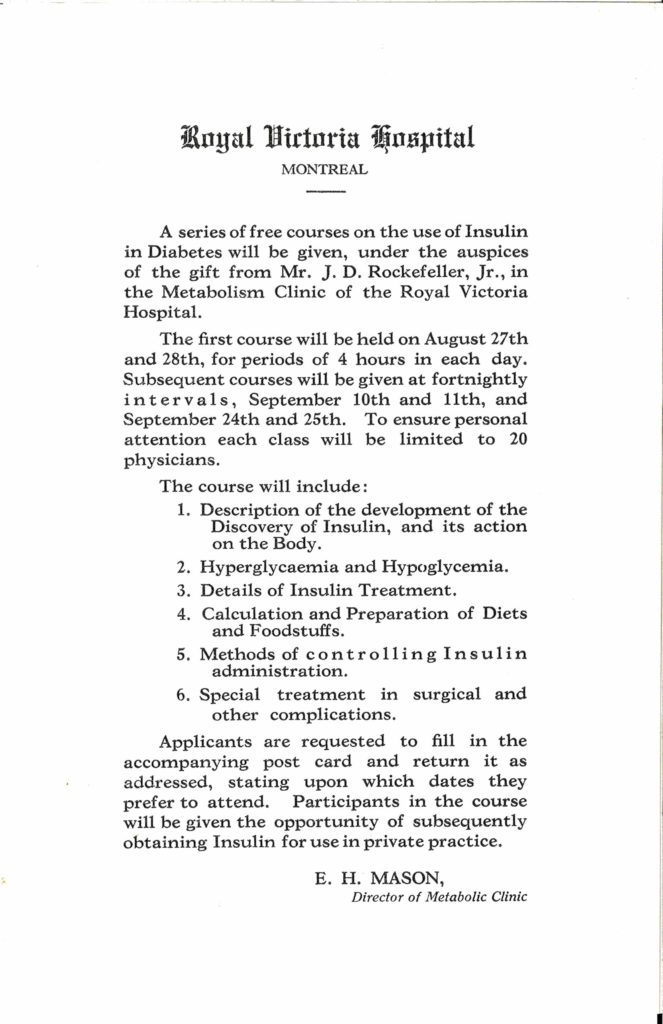

A portion of the funds was specifically earmarked to train physicians and their diabetic patients in proper insulin use. Today, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s gift is known as the “Insulin Gift.”

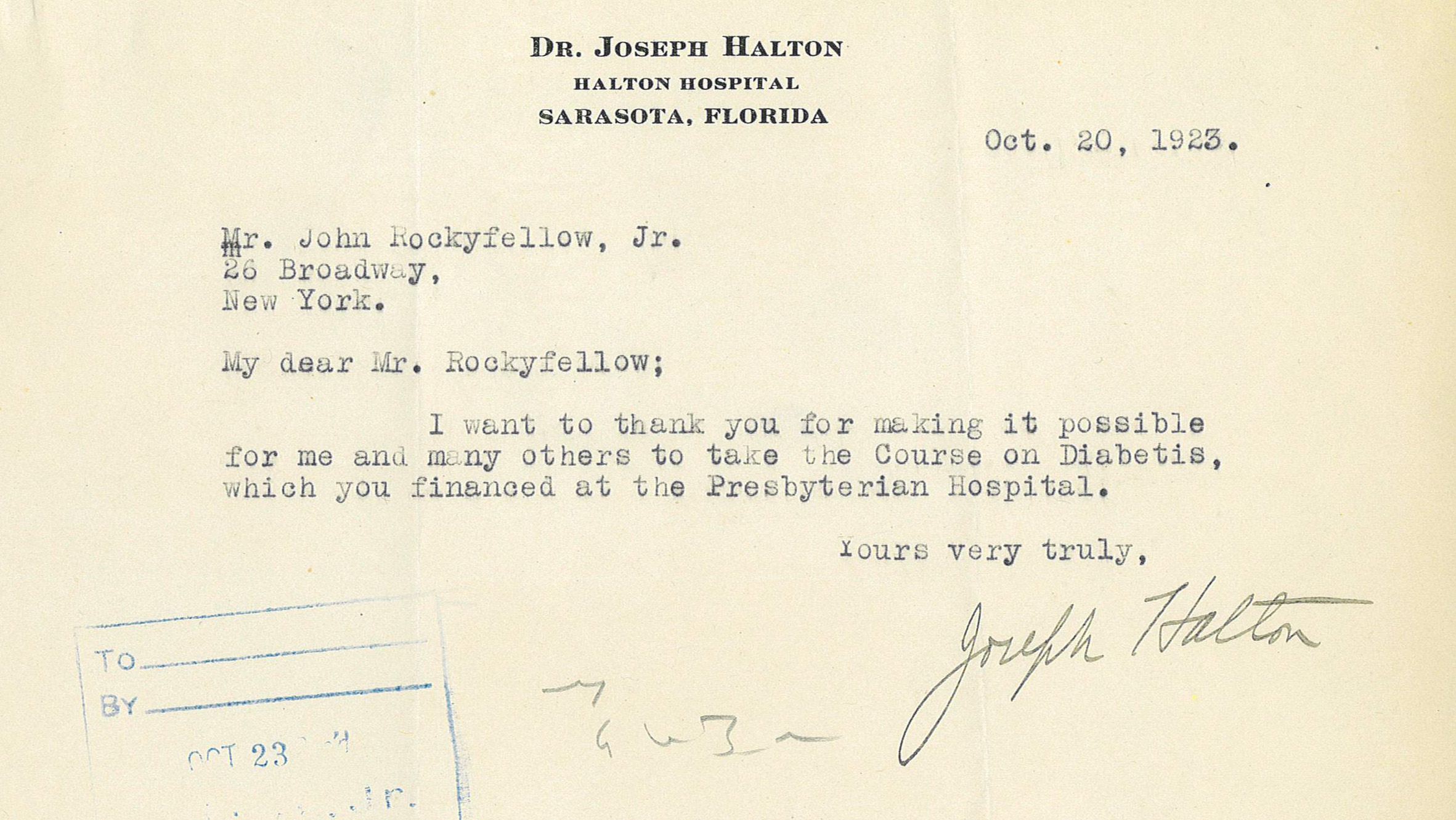

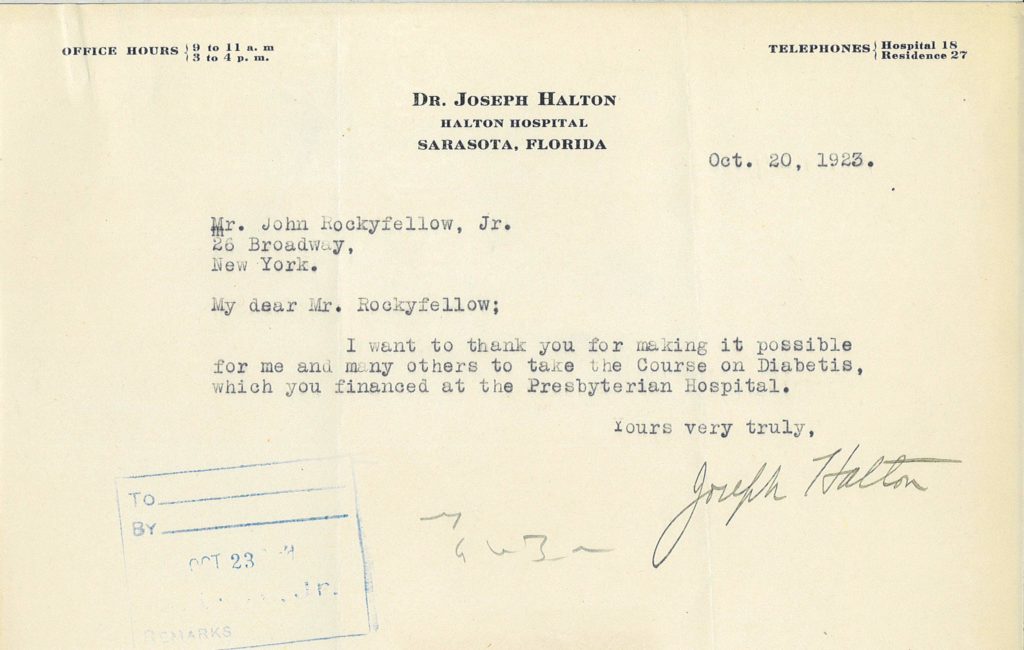

Covered by the press with great fanfare, the gift prompted many heartfelt personal letters from grateful patients and physicians.

These letters were filled with tales of children, as young as eight years old, who not only received insulin treatment but learned how to administer their own doses.Simon Flexner to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., October 30, 1923, Series III 20, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

By June 1925, seventeen hospitals had become beneficiaries of the “Insulin Gift,” leading to the expedited distribution of insulin, and rapid training of hospital staff and diabetic patients.Robert W. Gumbel to Margery K. Eggleston, June 1, 1925, Series III 20, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Today, JDR Jr.’s “Insulin Gift” remains a demonstration of the impact philanthropic giving can have on the adoption and dissemination of new medical treatments.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “Insulin Gift,” 1923, Frederick T. Gates papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Rockefeller Institute – Insulin – Treatment Pledge,” 1923-1933, Office of Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Institute, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Insulin,” 1892-1946, Simon Flexner Papers (American Philosophical Society), Series 1, Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (RIMR), Subseries 1.2, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Kleiner, Israel Simon,” 1892-1946, Simon Flexner Papers (American Philosophical Society), Series 1, Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (RIMR), Subseries 1.2, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Related

The Long Road to the Yellow Fever Vaccine

The yellow fever vaccine developed in the 1930s has been used worldwide ever since. Creating it took years and cost several lives. Some thought it would never happen.

The Commonwealth Fund Brings Hospice Care to America

Care for the dying, not care for a cure, was a new idea in the 1970s.

Photo Essay: The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission and the American South

Battling hookworm on rural farms laid the groundwork for a global public health system.

The Commonwealth Fund and the “Insanity Defense”: Unexpected Outcomes

Our understanding of the insanity defense relies on a book that was an unintended outcome of a Commonwealth Fund grant.