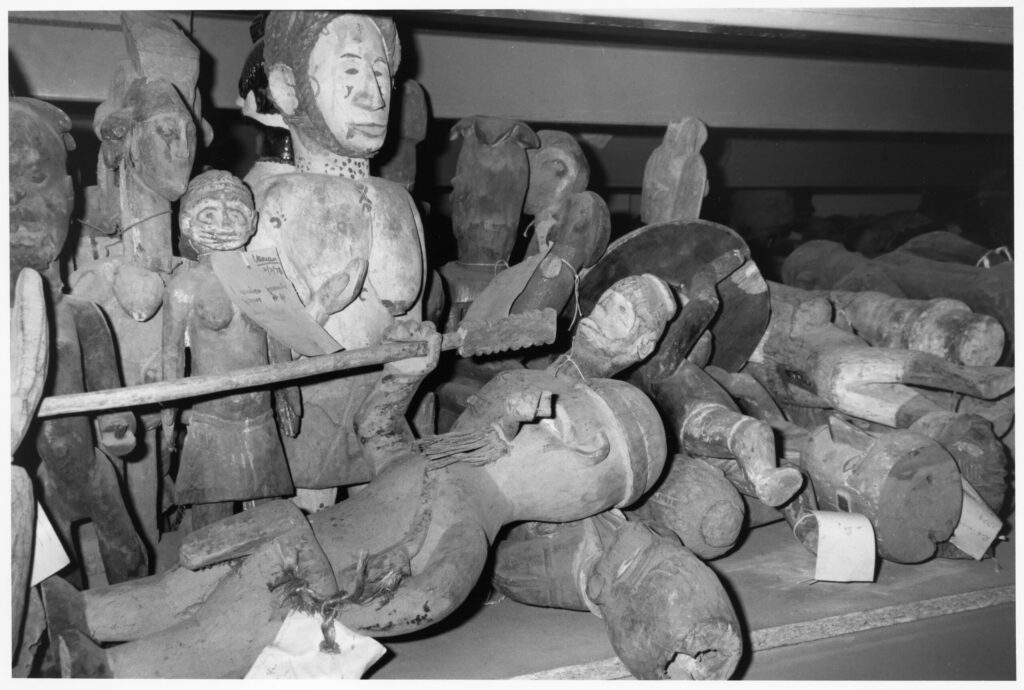

In the early 1980s, many West African museums were facing a fundamental problem: their collections were at risk of deteriorating because of insects, mold, heat, and a shortage of trained personnel.

Charles Gonyok, the museums director for Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments, explained:

We need proper storage racks, climate control, a dis-infestation program, trained conservators, and conservation materials. But we just don’t have the funds.“The Struggle to Conserve and Communicate.” Spring Report (Ford Foundation, 1993), 10. Ford Foundation records, Publications, Working Files and Photographs, Rockefeller Archive Center.

To respond to this cultural preservation crisis, concerned program officers at the Ford Foundation stepped up. In 1982, the West Africa Museums Programme (WAMP) was born, an independent organization based in Dakar, Senegal, with initial support from Ford, joined later, in 1989, by the Rockefeller Foundation.

From the beginning, WAMP went beyond simply repairing the physical decay of museum collections. It simultaneously focused on the people running the museums and what these institutions meant to local communities. To ensure the museums’ long-term viability, philanthropic funds helped support professional training programs through a network of universities and museums across western Africa.

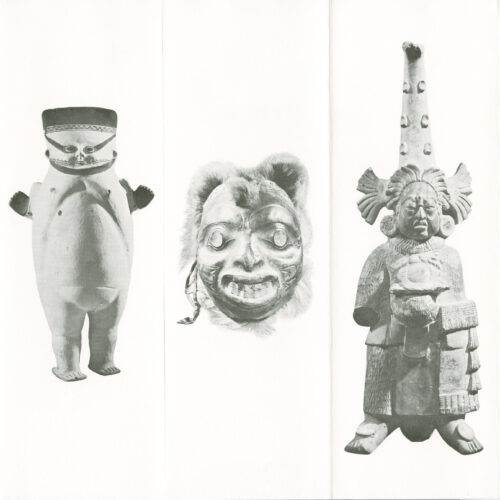

In its first decade of operations, WAMP supported museums in sixteen countries. Staffed by Africans, the museums would be re-imagined to fit a contemporary context more cognizant of African settings. In a 1993 interview, WAMP director Claude Ardouin explained: “Museums in West Africa have always been marginal institutions, created by Europeans in the classic ethnographic mold and visited mostly by tourists.”Spring Report (1993), 10.

That’s where the importance of the network came into play. Together, museum professionals could share strategies for better connecting to the communities they served. Ford-sponsored meetings enabled the network to flourish.

We must rethink the role of museums in Africa, to make them more relevant to our societies.

Claude Ardouin, 1993.

Today, WAMP’s founding vision has been substantially realized. Currently headquartered in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, it works with 200 museums in seventeen African countries. It has rescued and rehabilitated irreplaceable photograph collections, sponsored archaeological excavations and heritage preservation, documented and created databases for traditional art, craft, and technological processes, and trained museum professionals to respond effectively to conditions of war and natural disaster. WAMP consistently partners with the African Union, UNESCO, and ICOM (International Council of Museums), as well as major cultural institutions throughout Europe and the United States.

Further Reading

- Ana Temudo Gaio Lima, “Museum Development in Postcolonial West Africa, 1980-2000: A Reading from the Archives,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2025.