What role does popular media play in spreading disinformation? Can it drive a widespread social panic? Are there social, political, or educational factors that make some people more susceptible to fake news? These questions were as relevant in the years leading up to World War II as they are in our own era of deepfakes, “fake news,” and conspiracy theories. In the mid-1930s, program officers from the Rockefeller Foundation sought to answer basic questions about radio listening to understand better how people interacted with and responded to popular media.

By the end of the decade, the Rockefeller Foundation’s sister philanthropy, the General Education Board, was probing much darker questions about the power of radio to spread propaganda and provoke mass hysteria.

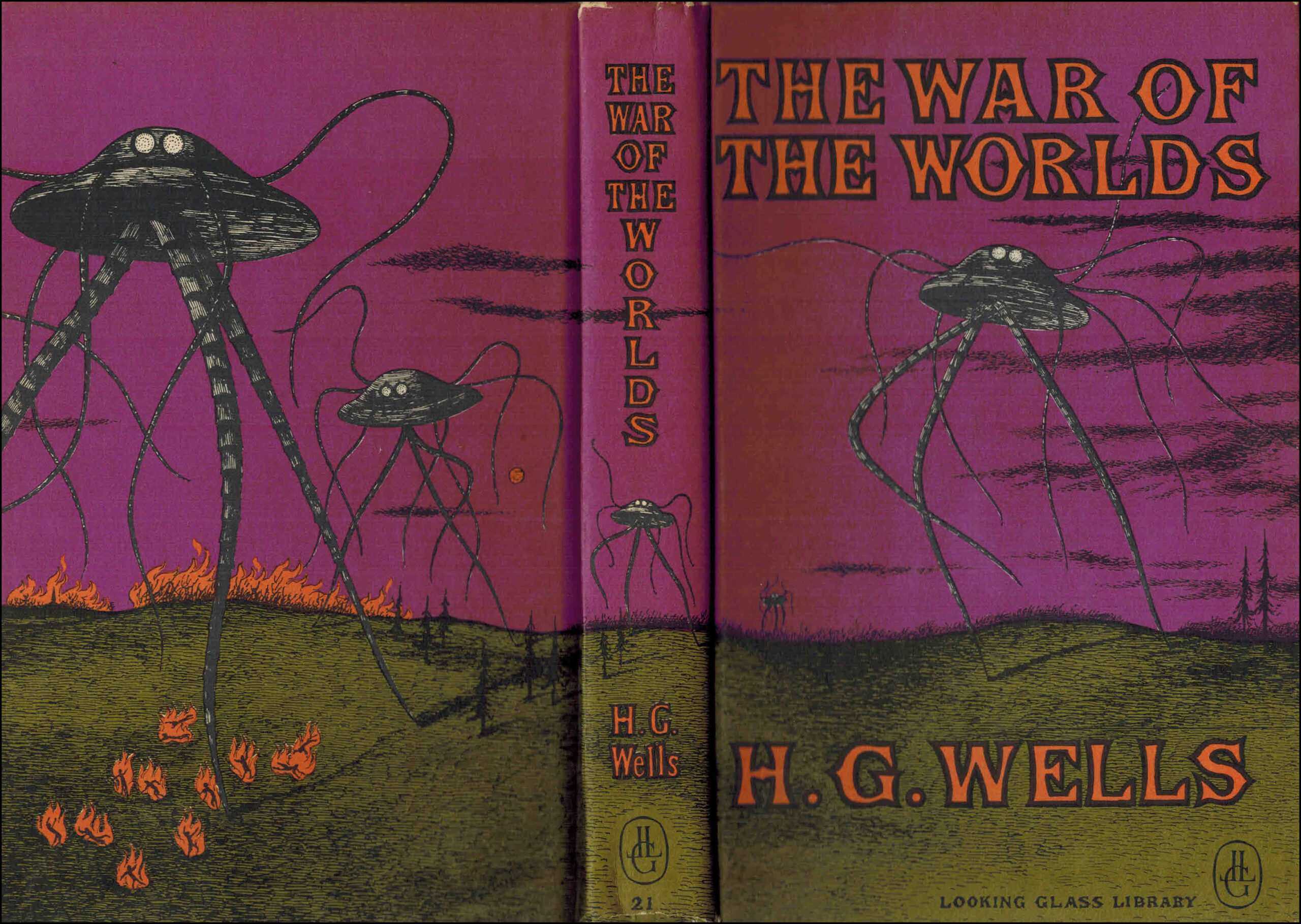

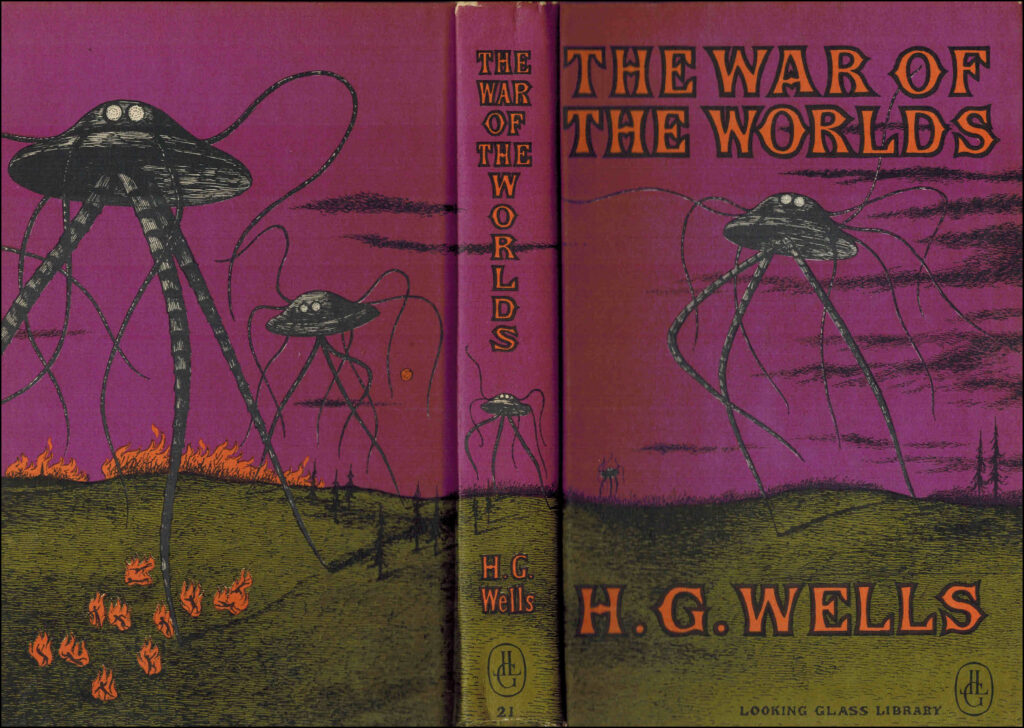

The War of the Worlds: A (Fictional) Martian Invasion

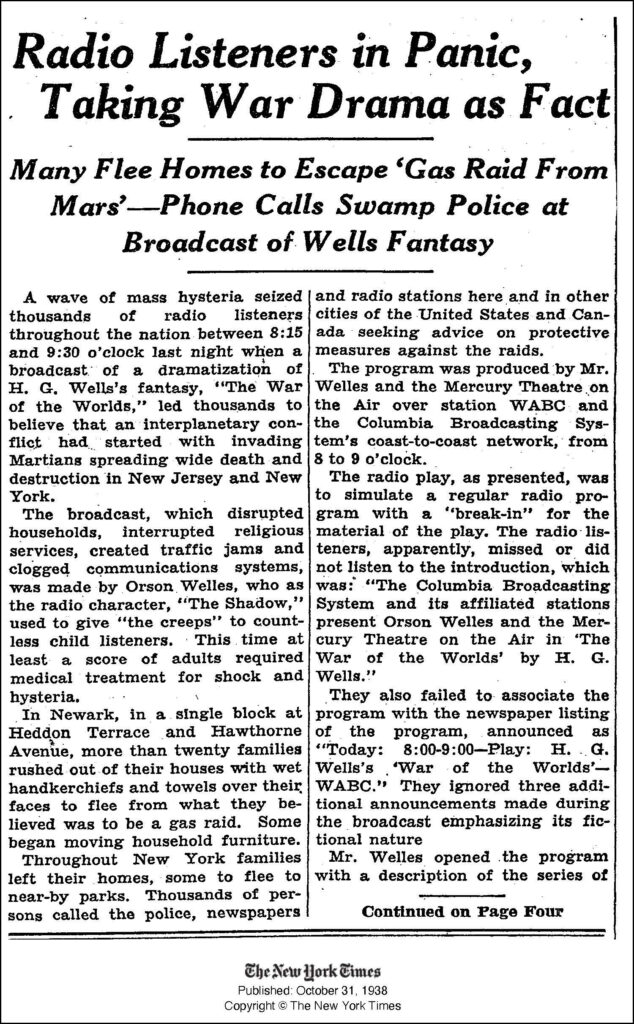

On Halloween morning in 1938, foundation program officers throughout the New York metropolitan area picked up their morning newspapers and were confronted with disconcerting headlines, including “Fake Radio ‘War’ Stirs Terror Through U.S.” (Daily News), and “Radio Listeners in Panic, Taking War Drama as Fact: Many Flee Homes to Escape ‘Gas Raid From Mars’” (New York Times).

At 8 pm the night before, radio performer Orson Welles presented an adaptation of H.G. Wells’s science fiction novel The War of the Worlds for his radio audience. If listeners tuned in a few minutes late, they might have missed cues that identified the CBS program as an episode of Welles’s radio drama Mercury Theatre on the Air and not, as the radio drama presented it, an interrupted orchestral concert.

That critical missing information led some listeners to believe the broadcast’s increasingly alarming “news bulletins” disrupting the “concert” were true.

They believed they were listening to live news coverage of an alien invasion in Grovers Mill, New Jersey.

Panic Over A “War of the Worlds”

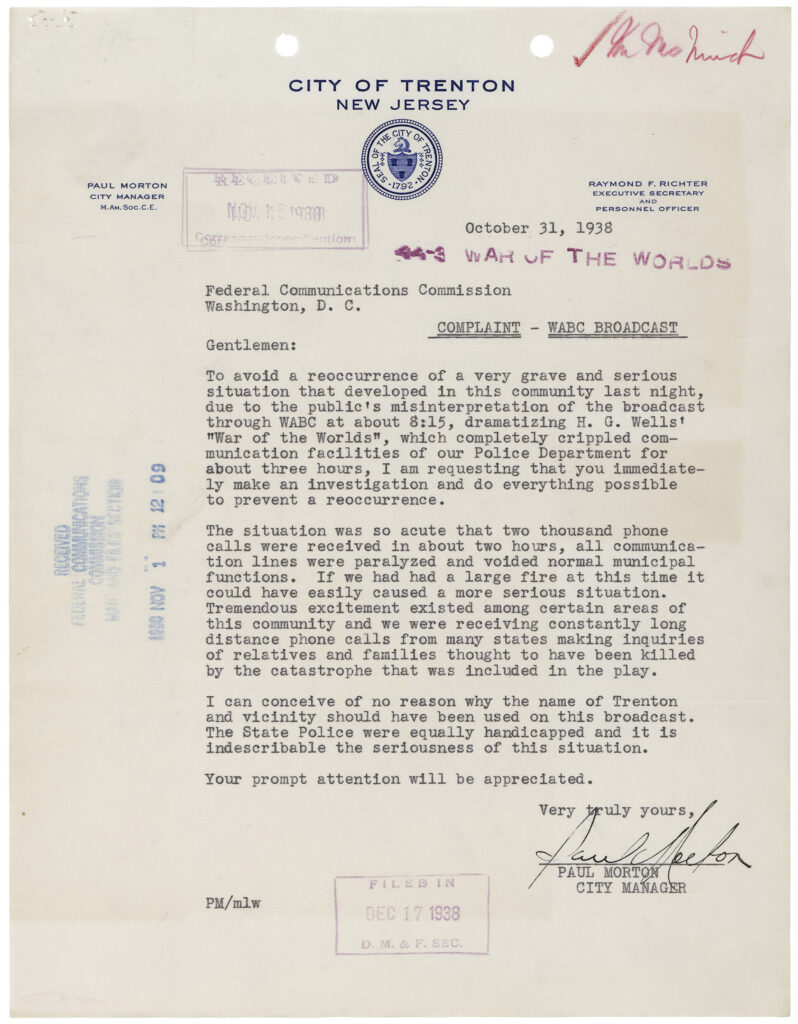

Newspapers reported that the broadcast caused traffic jams, deluged phone lines, and prompted residents to flee their homes in an effort to escape perilous Martian gas raids. In nearby Trenton, New Jersey, enough residents panicked that the city manager felt compelled to file a complaint about the broadcast with the Federal Communications Commission:

The situation was so acute that two thousand phone calls were received in about two hours, all communications lines were paralyzed and voided normal municipal functions.

Paul Morton, Trenton, New Jersey, City Manager, October 31, 1938

Scholars have rightfully called into question the true extent of the ensuing “panic,” but the fact that even a small slice of the public was frightened by the broadcast was alarming.

“Who Listens?”: The Rockefeller Foundation Explores the Promises of Radio

The War of the Worlds broadcast came at a time when foundations were beginning to explore the promises and perils of radio broadcasting. In the mid-1930s, Rockefeller Foundation program officers made grants to investigate the value and uses of new media forms, including radio and motion pictures. They recognized that radio had extraordinary educational potential, but that it was being used primarily for commercial profit rather than public service.

In 1935, the Foundation’s Humanities Division made grants to two nonprofits, the University Broadcasting Council in Chicago ($46,000) and the World Wide Broadcasting Foundation in Boston ($25,000) to develop educational and experimental radio programs. These grants sought to demonstrate radio’s potential as a public service both in the United States and around the world.Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1935, pp. 277-280.

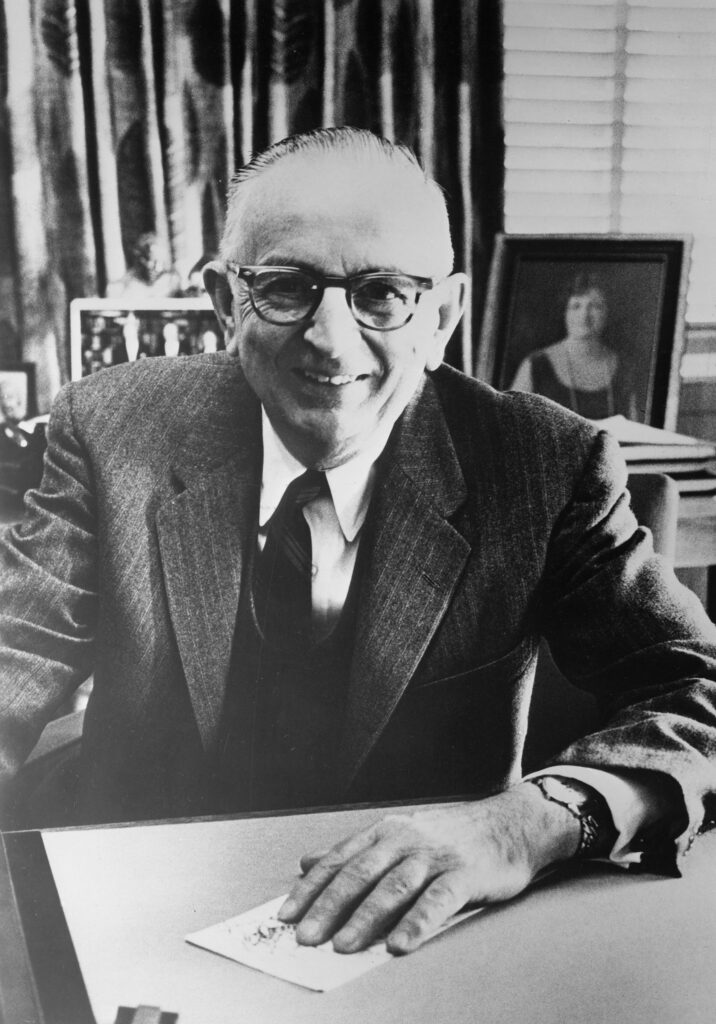

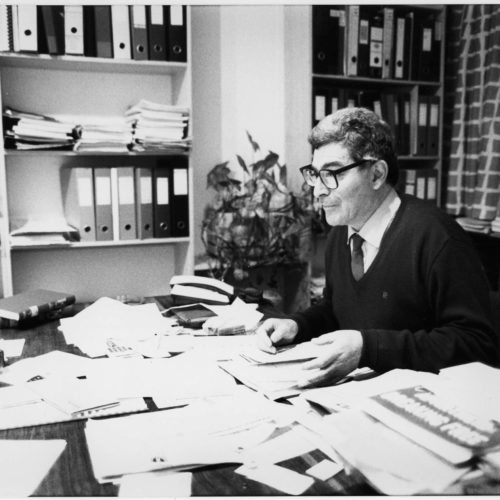

Then, in 1937, the Rockefeller Foundation gave $67,000 to the Princeton University Radio Research Project at the University’s School of Public and International Affairs to study the value of radio to listeners. This substantial grant — adjusted for inflation, more than $1 million dollars in 2021 — supported the work of sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld, social psychologist and Princeton professor Hadley Cantril, and CBS research director Frank Stanton.

Their project sought to answer basic questions about how and why Americans consumed radio: “Who listens? Where and when does listening take place? What is listened to? Why and how do people listen? What are the effects of listening?”Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1937, pp. 322-325.

Philanthropic support was critical to answering these questions. Although broadcasters had conducted extensive research about their listeners, this research was always guided by the industry’s bottom line. Rockefeller Foundation Humanities program officer John Marshall advocated for studies that instead assessed radio’s “audience not in terms of what it buys, but rather in terms of its needs, interests, and capacities.”John Marshall memo, May 1937, Princeton University – Radio Study, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1.1, United States, Series 200.R, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center. Foundations, untethered to concerns about profit, were perfectly positioned to support such research.

What are the effects of listening?

Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1935

“Mass Hysteria”: The General Education Board Explores the Perils of Radio

The public response to the War of the Worlds broadcast captured the imaginations of many foundation staffers, and brought a new sense of gravity to the Princeton Radio Project’s key questions.

How could a radio broadcast meant for public entertainment prompt seemingly rational individuals to be swept up in a mass panic? What could this reveal about the public’s susceptibility to disinformation and propaganda? On the eve of World War II, these questions loomed with ever-greater urgency. Lazarsfeld, Cantril, and Stanton began a new quest to answer them, by seeking funding for a study of the War of the Worlds broadcast and “mass hysteria”.

After the War of the Worlds Broadcast: A Flurry of Foundation Activity

A series of letters preserved in the General Education Board’s records provides a glimpse into conversations among staffers from various New York foundations over two days in November 1938.

On November 21st, Cantril and GEB program officer Robert Havighurst spoke about the proposed grant, and Cantril quickly followed up with an application.

The same day, Rockefeller Foundation Natural Sciences Director Warren Weaver wrote to Watson Davis, Director of the Science Service in Washington, D.C., to share his thoughts on the broadcast. He found “particular pertinency” in an article by journalist Dorothy Thompson in the New York Herald Tribune. He agreed with Thompson’s assessment that the broadcast revealed that:

…our popular and universal education is failing to train in reason and logic, even in the educated. […] popularization of science has led to gullibility and new superstitions…Warren Weaver to Mr. Watson Davis, November 21, 1938, Princeton Radio Research Project – Orson Welles Broadcast Study 1938-1944, General Education Board Records, Appropriations, Series 01, Secondary and Higher Education, Subseries 1.2, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Rockefeller Foundation Natural Sciences Director Warren Weaver, November 21, 1938

Also on November 21st, a staffer from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation reached out to Rockefeller Foundation Humanities Director David H. Stevens to encourage the Foundation to support the proposed study. It was outside of his own foundation’s field of work (medical research), he said, so he was sharing it in his “purely private, personal capacity because of my very keen interest in the radio and motion pictures as agencies for emotional education”.LKF to D. H. Stevens, November 21, 1938, Princeton Radio Research Project – Orson Welles Broadcast Study 1938-1944, General Education Board Records, Appropriations, Series 01, Secondary and Higher Education, Subseries 1.2, Rockefeller Archive Center.

A Concern about Media Literacy

On November 22nd, Stevens, in turn, followed up with S. Howard Evans, of the Payne Fund, which had a particular interest in the influence of radio and movies on children. The two had recently discussed Evans’ own interest in the proposed study, and Stevens wanted to keep him in the loop on the grant’s progress.David H. Stevens to Mr. S. Howard Evans, November 22, 1938, Princeton Radio Research Project – Orson Welles Broadcast Study 1938-1944, General Education Board Records, Appropriations, Series 01, Secondary and Higher Education, Subseries 1.2, Rockefeller Archive Center.Next, Stevens also joined Havighurst for an in-person interview with Cantril and Lazarsfeld on the 22nd. The group hammered out some remaining details for the study, including the General Education Board’s provision (ultimately unfulfilled) that the study be adapted into an educational report tailored to grade school and college students.

In just a few short days, these disparate conversations coalesced around a $3,000 grant from the General Education Board to the Princeton Radio Project for a study of public reactions to the War of the Worlds broadcast.

New Media, New Anxieties About Propaganda and Disinformation

Why were so many foundation officers captivated by the response to the War of the Worlds broadcast?

It came at a moment when fascination with the influence and reach of new media forms collided with fears about the rise of totalitarianism and the power of propaganda. On the eve of World War II, Americans were closely watching the rise of authoritarian governments in Germany, Italy, the Soviet Union, and Japan.

Cantril and Lazarsfeld–himself a Jewish Austrian emigre–saw the broadcast as a means to better understand how individuals fall prey to propaganda and misinformation. (It was also, of course, an opportunity to secure additional funding for their existing Rockefeller Foundation-supported research program.)See also Joseph Malherek, “Radio Research and Refugee Scholars: American Philanthropies Respond to the European Crisis before the War, 1933-39.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2018.

In his grant proposal, Cantril identified the public reaction to the War of the Worlds broadcast as “an almost unparalleled source of data” for those interested in understanding the impact of radio on mass movements. It would also be of use to educators troubled by what the response to the broadcast suggests about “critical thinking and propaganda.”Hadley Cantril, “Proposed Study of ‘Mass Hysteria,’” Princeton Radio Research Project – Orson Welles Broadcast Study 1938-1944, General Education Board Records, Appropriations, Series 01, Secondary and Higher Education, Subseries 1.2, Rockefeller Archive Center. It was a persuasive argument for program officers seeking to understand more clearly how propaganda works, and how to better educate Americans in media literacy.

“A Study in the Psychology of Panic”

The final study reached a broader audience when Cantril published it as The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic in 1940. The research team sought to understand why the broadcast terrified many listeners, and what made those individuals susceptible to misinformation. The researchers only interviewed people who reported being frightened by what they heard, and only people in New Jersey—where the “invasion” supposedly took place.

The Invasion from Mars study highlighted the experiences of the most frightened individuals within the interviewee group, thereby sensationalizing what was in fact a much more nuanced dataset. In reality, only about a third of those interviewed for the study believed that they were listening to coverage of an alien invasion; most others believed it was a foreign invasion or natural disaster. Every interviewee had also turned on the radio program late, and missed the cues that identified it as Welles’s radio drama.

All of these nuances were overshadowed by the study’s sensationalist writing style.

Ironically, Cantril’s published study helped contribute to the oversimplification and exaggeration of the “mass hysteria” that the broadcast supposedly caused. Importantly, it also largely erased the labor of the several women who conducted the interviews and research for the study, especially Princeton Radio Project researchers Herta Herzog and Hazel Gaudet.For more on the study itself, see A. Brad Schwartz, Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News (New York: Hill and Wang, 2015); and Jefferson Pooley and Michael J. Socolow, “Chapter Two: War of the Words: The Invasion from Mars and Its Legacy for Mass Communication Scholarship,” in Joy Elizabeth Hayes, Kathleen Battles, and Wendy Hilton-Morrow, eds., War of the Worlds to Social Media: Mediated Communication in Times of Crisis (New York: Peter Lang, 2013). The grant’s educational component (which Havighurst had stipulated as a requirement for the grant) was not completed.

The Power and Potential of New Media

Although Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds broadcast was, at best, a minor national event, it had an outsized cultural impact by illuminating the power and potential of radio broadcasts.

By 1940, as the U.S. inched closer to war, the questions raised by the Princeton Radio Project and the War of the Worlds broadcast were no longer theoretical. In 1940, the Rockefeller Foundation was supporting The New School for Social Research’s “Study of Totalitarian Communication in Wartime,” led by Ernst Kris and Hans Speier, to analyze radio broadcasts in totalitarian countries.New School for Social Research – Totalitarian Communication Studies, Rockefeller Foundation Records, RG 1.1, Series 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

For both the Rockefeller Foundation and General Education Board, the War of the Worlds broadcast hinted at issues that would become front and center as the nation entered World War II, especially the potential uses (and misuses) of radio and other mass media in galvanizing public sentiment and opinion. The GEB-funded study bridged the optimism driving the RF’s support for experimental broadcasting and the Princeton Radio Project in the mid-1930s, and its support for more urgent research about radio and propaganda by the early 1940s.