At the end of the 19th century, modern art emerged as a movement that questioned realism and moved toward the abstract. Because modernism rejected traditional form, techniques, and subject matter, it wasn’t immediately embraced by the art establishment. Modern art made its American debut at the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, also known as the Armory Show. By the late 1920s, individual collectors had begun to appreciate this new art form, but there was no major institution dedicated to exhibiting modern art in the United States.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and Modern Art

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, the matriarch of the Rockefeller family’s second generation, founded New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1929 with friends Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan, giving modernism a dedicated showcase. Abby’s taste in art was in stark contrast to that of her husband, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who himself would found the Met Cloisters museum in 1938, to showcase Medieval art.

Over lunch in 1928, three women launched the radical idea of founding a museum in New York just to exhibit modern art. As Abby Aldrich Rockefeller recalled, “I began to think of women whom I knew in New York City, who cared deeply for beauty and who bought pictures, women who would be willing, and had faith enough, to help start a museum of contemporary art.”

MoMA Through Time

Modern Art and Nelson Rockefeller

Abby’s son Nelson Rockefeller served MoMA as its first president beginning in 1939, when it moved into its permanent home. In fact, as Abby worked to launch the new institution, she envisioned it as an ideal outlet for Nelson’s interest in art patronage and collecting. Of all her children, Nelson’s love of art and his aesthetic taste aligned most closely with hers. At MoMA as well as the family’s other major venture of the 1930s, Rockefeller Center, Abby viewed Nelson as someone who might “hold the fort for the modern.”Richard Norton Smith, On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller. (New York: Random House, 2014), 6.

Not only as president, but as chairman of MoMA’s Junior Advisory Committee, Nelson applied personal charisma and political savvy to earn the museum wide recognition, and proved to be an expert fundraiser. MoMA quickly became a global influencer, introducing its visitors to artists like Picasso and Matisse, as well as to the International Style of architecture pioneered by Gropius, Le Corbusier, and others. For the rest of his life, Nelson continued to promote and expand the cultural institution we know today.

Many other Rockefeller family members have also served on the MoMA board of trustees. These have included Abby’s youngest son, David Rockefeller (who joined the board in 1948 and subsequently engaged renowned architect Philip Johnson, director of the Department of Architecture at MoMA, to redesign the Sculpture Garden), as well as Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller, David Rockefeller, Jr., and Sharon Percy Rockefeller.

Abby Rockefeller, wife of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was so intrigued by modern art – and especially by the artist Arthur B. Davies – that, along with two other women, Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan, she started the Museum of Modern Art in a rented space at 730 Fifth Avenue in New York in 1929. All three women believed the US needed an institution that would actively champion modern art.

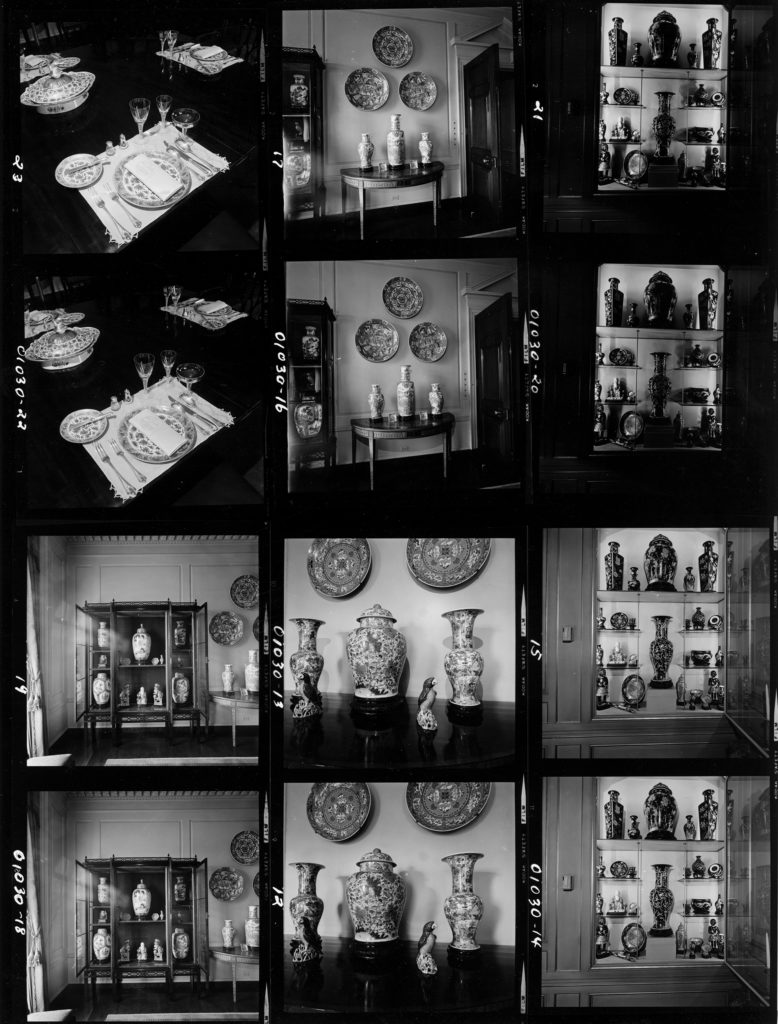

Abby’s taste in art was quite the opposite of that of her husband, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who enjoyed Chinese porcelains and Medieval art. Their townhouse at 10 West 54th St. in New York City (on land later donated to provide the site for MoMA’s sculpture garden) was the childhood home of Nelson and his five siblings.

On the top floor of their home at 10 West 54th Street, in her children’s former playrooms, Abby curated two gallery spaces (designed by Donald Deskey, who also designed the interiors of Radio City Music Hall), mixing modern art with her collection of American folk art and with some pieces from her husband’s collection. This is the larger gallery of the two.

Nelson Rockefeller took after his mother in his love for modern art. Working with MoMA’s first director, Alfred H. Barr, Nelson raised over $1 million in the early 1930s for the new museum.

In addition to art, Nelson had a lifelong interest in the culture and politics of Latin America.

Frida Kahlo’s husband, the famous muralist Diego Rivera, had the second solo-artist exhibition at MoMA in 1932.

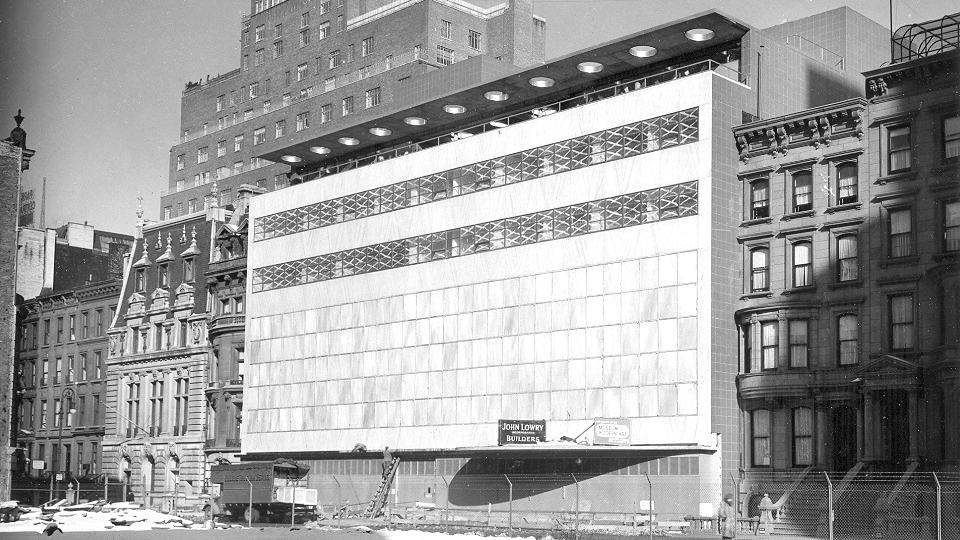

In the late 1930s, Abby and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. donated their townhouse, as well as land on 53rd Street, for the site for the new MoMA.

The museum’s new building was completed in 1939. It was designed by Philip L. Goodwin (a MoMA trustee) and Edward Durell Stone.

The new construction also included a sculpture garden designed by MoMA architecture curator John McAndrew and director Alfred H. Barr.

The Sculpture Garden, opened in 1939, was redesigned by architect Philip Johnson in 1952. When it reopened in 1953, the garden was named in honor of Abby, who had died in 1948.

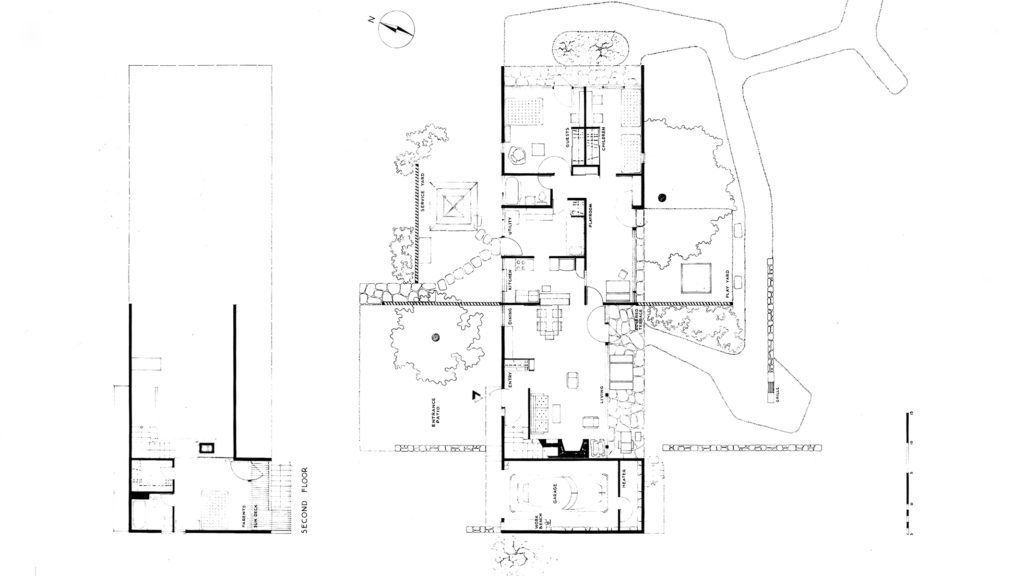

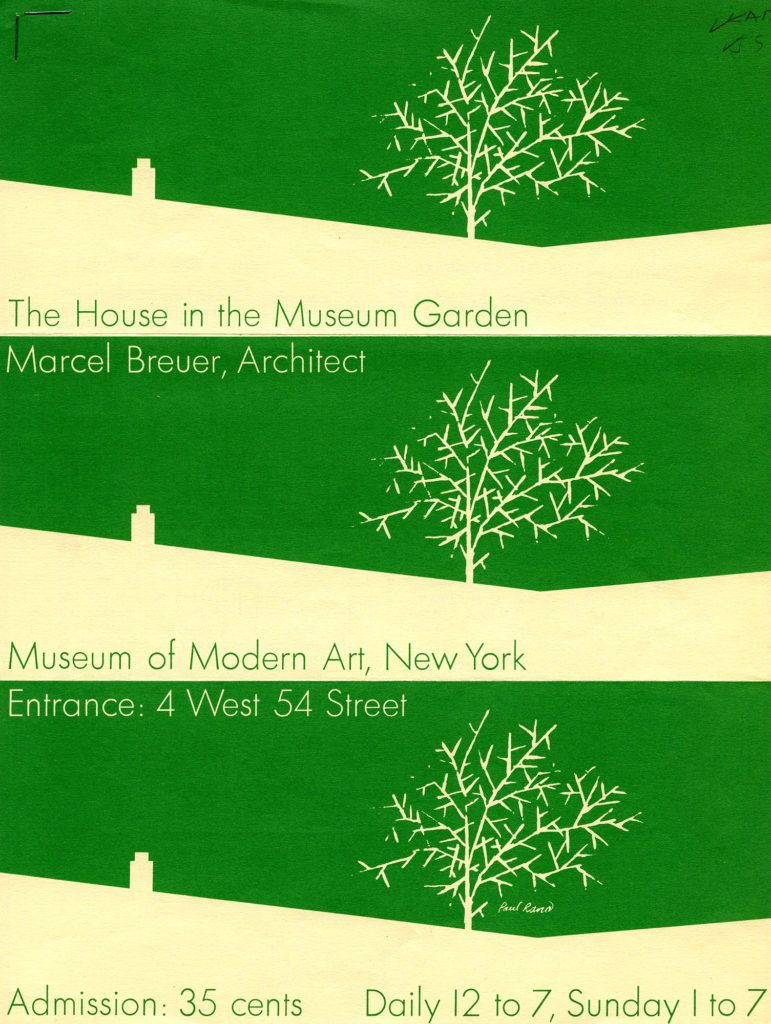

The garden’s exhibitions included one featuring a house designed by modern architect Marcel Breuer. At the end of the exhibition, Nelson Rockefeller purchased the house and had it moved to Kykuit, the Rockefeller estate in Pocantico Hills, NY, where it stands today.

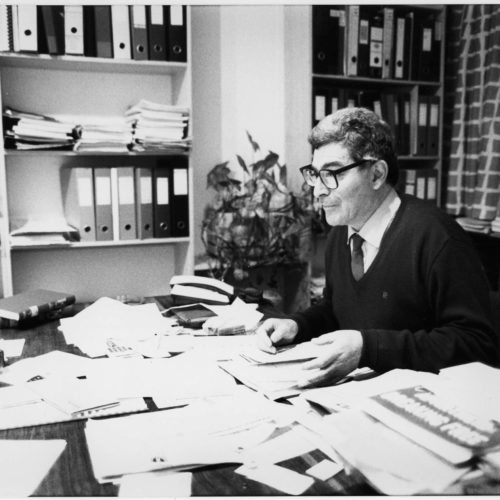

In 1939, Nelson became president of MoMA. Here he stands with René d’Harnoncourt, MoMA’s second director (1949-1967), in 1950.

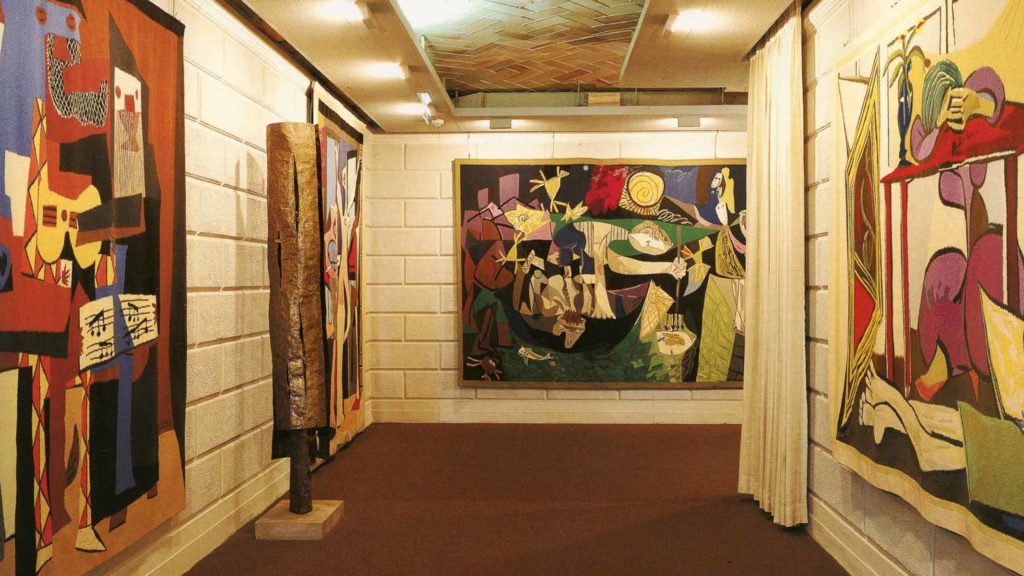

Much like his mother, Nelson created a home art gallery when he lived at Kykuit during his governorship of New York (1959-1973). It featured tapestries designed by Pablo Picasso and works by Alexander Calder, Andy Warhol and many other artists.

Nelson also wanted to see art outside. He adorned the land around the Kykuit estate with outdoor sculptures, some flown in via helicopter.

Installing part of Knife Edge Two Piece, a large sculpture by Henry Moore at Kykuit.

A Calder piece titled Large Spiny can also be viewed at Kykuit today, which is now a part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The mother and son, pictured here in 1908, whose love for modern art built a lasting institution to share with generations to come.

Further Reading

- Eliza Butler, “Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and American Modernism at MoMA.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2025.

- Elisabeth Magotteaux, “The Artist and the “Art Connoisseur”: Fernand Léger’s Artworks in Nelson A. Rockefeller’s Collection.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2024.