On May 10, 1938, The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s (The Met’s) Cloisters museum opened to the public. Situated at the top of a hill and nestled among the forest and meandering paths of Upper Manhattan’s Fort Tryon Park, The Cloisters museum was built to showcase selections from The Met’s medieval European collections as well as related special exhibitions. But the building itself is also a fascinating part of the collection–a hybrid construction of various European cloisters and secular buildings acquired at a time when the American market for European architectural salvage was on the rise. John Harris, Moving Rooms: The Trade in Architectural Salvage (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

European Antiques for an American Cloisters Museum

At The Met Cloisters, pieces of the twelfth-century Cuxa Cloister from the monastery of St-Michel-de-Cuxa in southwestern France and the Saint-Guilhem Cloister from the Benedictine abbey of St-Guilhem-le-Désert in southern France encircle respective interior courtyards, while masterworks such as Robert Campin’s c. 1427-32 Merode Altarpiece and the seven 1495-1505 Netherlandish wall hangings comprising “The Unicorn Tapestries” cycle adorn The Cloisters’ interior walls. Though the modern assemblage of medieval objects and buildings feels coherent, a visitor to The Cloisters is actually traveling through a wide variety of centuries and locations.

For an institution as unique as The Cloisters museum, it is then only fitting that two of the most important men behind its creation were individuals who were equally disparate, brought together by circumstance, opportunity, and a shared appreciation for medieval art: John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and George Grey Barnard.

Portrait of Opposites

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (JDR, Jr.) was the only son of John D. Rockefeller, the world’s first billionaire and the founder of Standard Oil. Choosing to eschew the family oil business in favor of a career in the family’s other prominent endeavor, institutional philanthropy, Rockefeller, Jr. became a twentieth-century pioneer of major philanthropic giving. He was also a connoisseur of Chinese porcelain and European medieval art, and a devoted proponent of public parks and the natural world, among other accomplishments and interests.

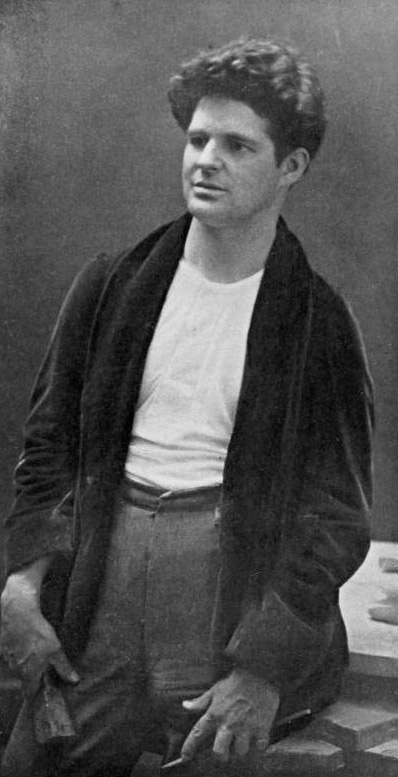

George Grey Barnard was a noted but perennially in debt sculptor who turned his side businesses as a European medieval artifacts dealer into a lucrative, and headline-grabbing gig. Nicknamed by his supporters, the “modern Michelangelo,” some of Barnard’s more famous artistic works include his 1888 Struggle of the Two Natures in Man, which was celebrated at the 1894 Paris Salon, his 1917 commemorative sculpture of Abraham Lincoln in Ohio, and the several sculptures he completed for the Rockefeller family’s Kykuit estate, including his 1923 Adam and Eve Fountain. Barnard was also a man who communicated in a “flux of bird-like words,” but one who JDR, Jr. noted was not “the most competent person to handle a business transaction.”William Welles Bosworth to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., September 14, 1916; and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to William Welles Bosworth, April 28, 1916, Series E, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

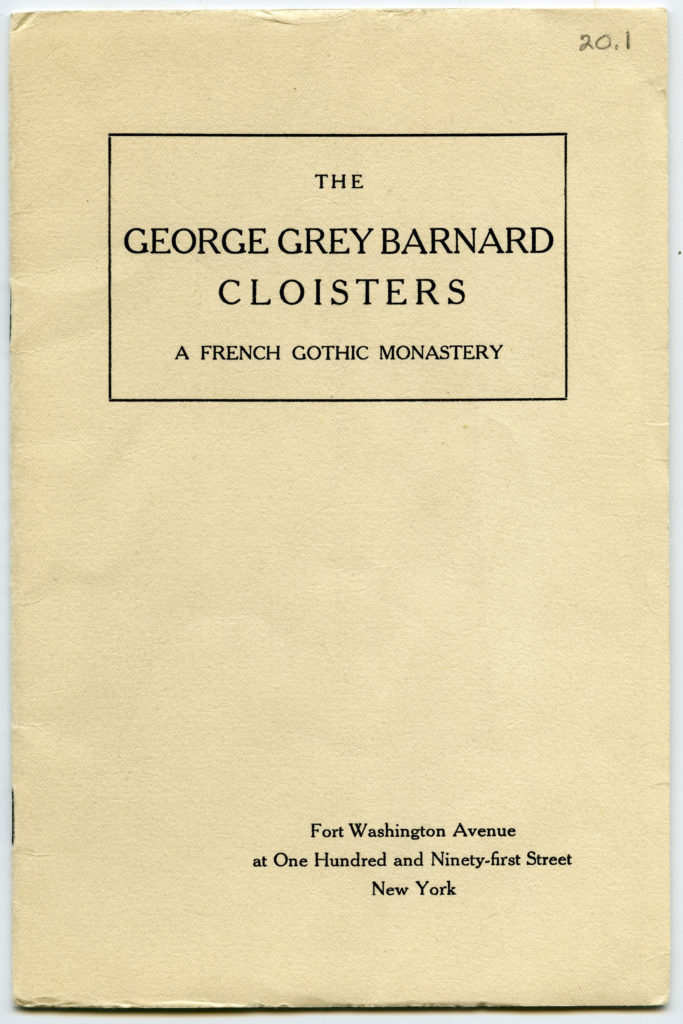

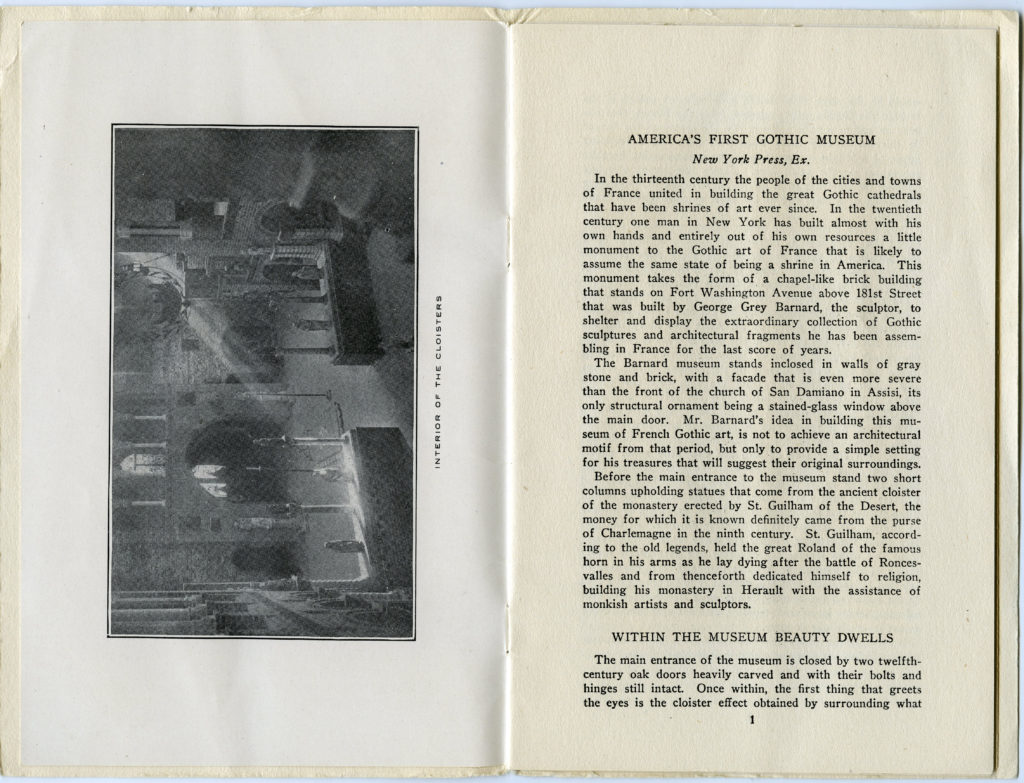

An Earlier Version of a Cloisters Museum

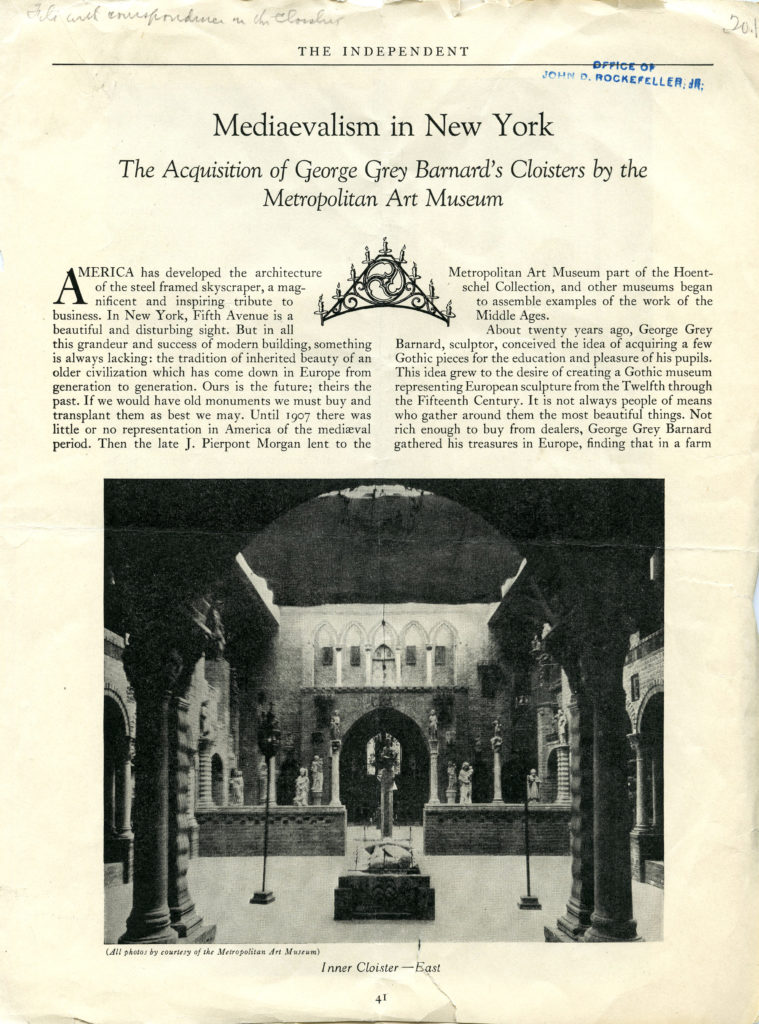

Beginning in 1914, Barnard put a core group of medieval artworks on display in his original Cloisters site on Fort Washington Avenue in New York City’s Washington Heights. Barnard’s original Cloisters museum was adjacent to his art studio and near his own residence, and he constructed his medieval composite building with a mix of Christian exaltation and aesthetic devotion—a combination not uncommon at the time.Timothy B. Husband, Creating the Cloisters (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), 10-11.

In 1916, Barnard reached out to Rockefeller, Jr. to see if he might be interested in purchasing his collection of medieval artworks and architectural fragments as well as land near Barnard’s Washington Heights home so that they could be better displayed.

To JDR, Jr., Barnard described his collection as possessed of “values of great aid to our artists, painters sculptors architects etc. [sic]” and argued that

people needed a true living expression of those glorious old Abbeys and Cathedrals of the Old World here to step within…

George Grey Barnard to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., April 1916, emphasis original. George Grey Barnard to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., April 1916, Series E, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Such a showcase for his artifacts Barnard defined as his “gift to our people—a gift of love.” George Grey Barnard to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., April 1916, Series E, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Purchasing the Perfect Site for The Met Cloisters

JDR, Jr. agreed to proceed with a purchase, thus marking the inception of today’s Cloisters museum with the acquisition of one hundred of Barnard’s objects. At the same time, in collaboration and consultation with The Met, JDR, Jr. also began the process of acquiring land in Washington Heights, which would eventually become Fort Tryon Park, within which the new Met Cloisters museum was housed. He also financed a landscape design program by the Olmstead Brothers firm, helmed by the children of Frederick Law Olmstead, the famous designer of New York City’s Central Park. Rockefeller, Jr. ultimately donated Fort Tryon Park to New York City with the understanding that the City would see to its maintenance and the installation of utilities and other practicalities.Husband, Creating the Cloisters, 15-17, 28-29.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s Personal Gift

Before the completion of The Met Cloisters, however, JDR, Jr. had no place to display the objects he had acquired from Barnard. He first put the pieces in storage and then later displayed them in Kykuit’s service tunnel before transferring them officially to The Metropolitan’s collections and their present Cloisters home.John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to William Welles Bosworth, April 24, 1916, Series E, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Husband, Creating the Cloisters, 15. In addition, Rockefeller, Jr. gifted his own collection of medieval artworks to The Met Cloisters, including his prized “Unicorn Tapestries”–acquired in 1922 through a tip from Barnard and which JDR, Jr. had displayed in the dining room of his family’s New York City townhouse. JDR, Jr. also provided the Museum with specific funds allocated for The Met’s long-term stewardship and preservation of the collection.Husband, Creating the Cloisters, 18

The Cloisters museum then equally bears the imprint of both Rockefeller, Jr. and Barnard, and is a testament to each man’s vision and foresight. However, though today’s Met Cloisters is the fruit of an inherently joint endeavor by JDR, Jr. and Barnard, such a joint endeavor was fraught, to say the least. One might indeed describe The Cloisters as a project realized despite, not because of, the relationship between the two men.

A Clash of Style and Temperament

This tension had its origins in a Barnard sculpture commissioned by JDR, Jr. and his father for the family’s Kykuit home in Pocantico Hills, New York. The sculpture, the Adam and Eve Fountain, was a project beset by innumerable delays—begun in 1916 but completed in 1923—with increasingly escalating costs. Great financial drama was generated by both Barnard and his wife–drama that included George Grey Barnard’s forgery of a letter to JDR, Jr. requesting a financial advance and purportedly written by the project’s supervising architect, William Welles Bosworth.Frederick C. Moffatt, “Re-Membering Adam: George Grey Barnard, the John D. Rockefellers, and the Gender of Patronage,” Winterthur Portfolio 35, No. 1 (Spring 2000): 53-80, 79. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to George Grey Barnard, January 21, 1922; and Edna Monroe Barnard to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., February 2, 1922, Series I, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

But the clash between the two men was not only financial. Despite the fact that JDR, Jr., Barnard, and Barnard’s workmen had settled on the appearance of the nude Adam, Barnard, in the last phases of completing the Adam, tried to argue afresh with JDR, Jr. in favor of emphasizing Adam’s nude genitalia—suggesting that he replace the modesty “clouds” strategically placed on the Adam sculpture. JDR., Jr. agreed to have Barnard experiment with a modesty fig leaf instead, and requested Barnard’s unwarranted changes to Adam be “obliterated.”George Grey Barnard to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., August 27, 1923; John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to George Grey Barnard, October 29, 1923; and John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to George Grey Barnard, November 28, 1923, Series I, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center. However, various edits on the sculpture played out for several years, as JDR, Jr. continued to press Barnard to make requested changes to the Adam and Eve Fountain well into 1927, and most times to no avail. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to George Grey Barnard, May 11, 1927, Series I, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Cloisters Museum Prevails Despite a Stand-Off

All of this occurred simultaneous with the development of The Met Cloisters, and the disagreements over the Kykuit sculpture combined with Barnard’s extensive financial and time management difficulties, made JDR, Jr. ill-disposed to engage personally with Barnard over the course of the creation of The Cloisters museum.

Writing to the director of the Met, Robert W. DeForest, in 1929, Rockefeller noted:

…you will of course appreciate my attitude in the matter and realize from what you know of my previous relations with Mr. Barnard that I cannot do business with him, nor is it wise for me to have any personal contact with him.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to Robert W. DeForest, April 24, 1929.John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to Robert W. DeForest, April 24, 1929, Series E, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In correspondence throughout the development of The Met Cloisters, similar sentiments regarding Barnard are expressed by JDR, Jr. and his team, as Barnard made it challenging for Rockefeller, Jr. to acquire additional land to move The Cloisters. Robert W. DeForest to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., October 19, 1927, and Charles O. Heydt to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., February 29, 1928, Series E, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to George Grey Barnard, December 1930, Series E, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Beneath the surface of The Cloisters’ origin narrative then lies the incompatible relationship between the two men who principally enabled the Museum to come into being. The story of Barnard, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and The Met Cloisters museum is one in which, in the service of societal benefit, the pursuit of beauty, and the promotion of culture, philanthropy sometimes makes quite strange, and unexpected bedfellows.