The 1932 appointment of mathematician Warren Weaver as Director of the Natural Sciences marked the expansion of Rockefeller Foundation endeavors to the newly emerging field of computer science. The Foundation had long invested in physics and chemistry through the work of the International Education Board (IEB) in the 1920s and its own support for National Research Council fellowships. In the 1930s, as Weaver developed targeted programs of research, advances in mechanical calculating devices showed significant promise for machine solutions to complex problems that Weaver and his staff quickly recognized.

“A Roomful of Brains”

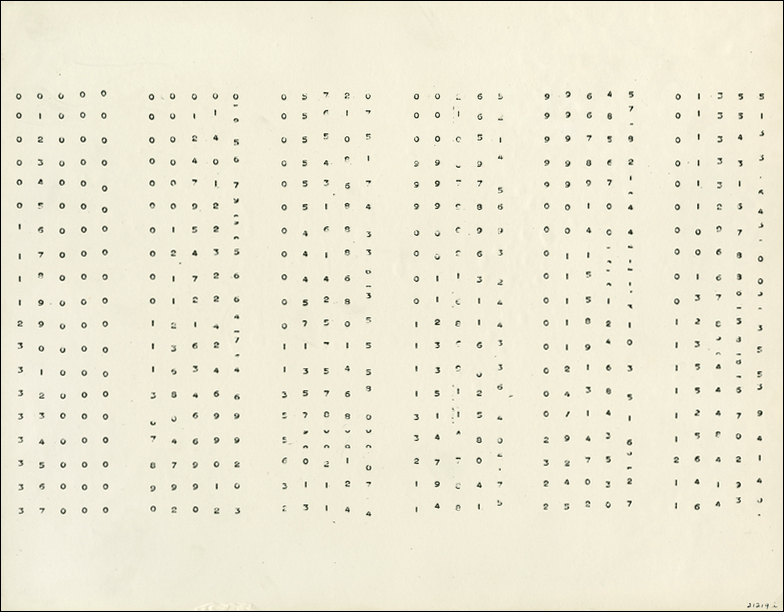

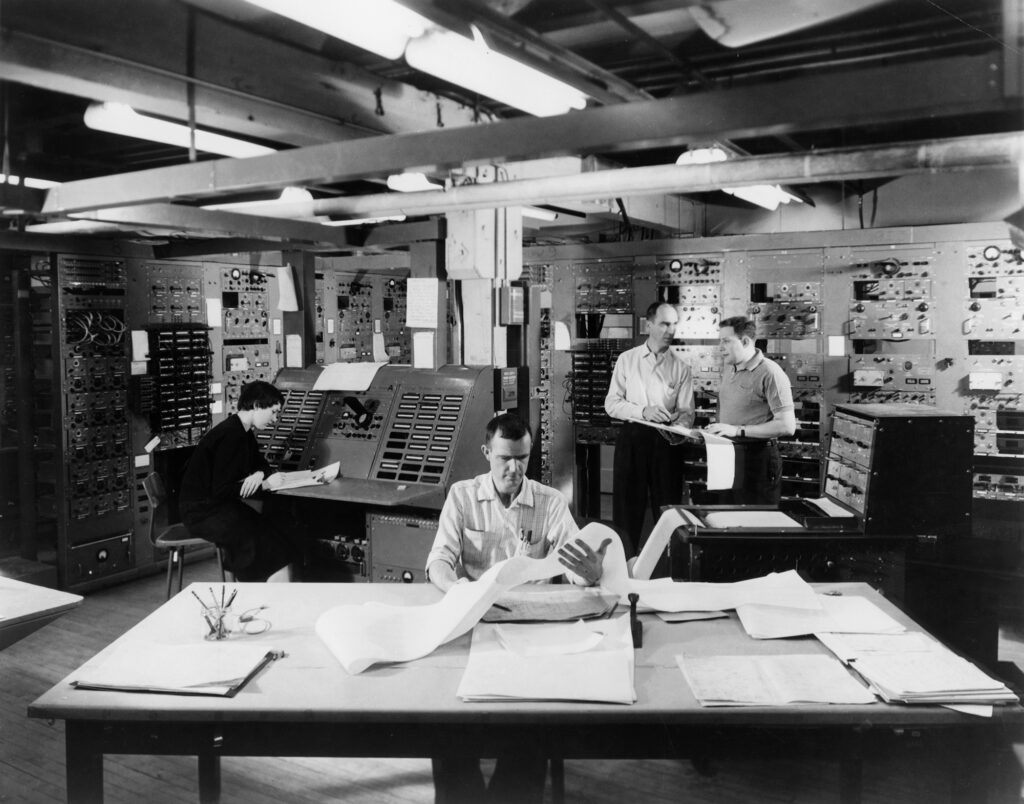

In the 1930s, the Foundation underwrote Vannevar Bush’s massive analog computer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which was finally dedicated in 1942 and named the Rockefeller Differential Analyzer.Gray, George, W., “A Roomful of Brains,” December 17, 1937, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 1.1, Series 224.D, Box 2, Folder 23. One of the largest and last of the mechanical analog computers, it weighed 100 tons, used 2,000 vacuum tubes and 150 motors. Called “analog” because it carried out an analogy of a real physical process, the machine was touted as revolutionary in mechanized calculus. It operated in real time and, unlike later digital computers, did not require a program to translate high language to binary machine language.

Merging Biology and Mathematics

In the 1940s, Rockefeller Foundation funding helped mathematician Norbert Wiener develop the new field of cybernetics. Wiener published his landmark book, Cybernetics, in 1948, after the Foundation’s grant to his joint project with cardiologist Arturo Rosenbleuth to study feedback loops in the human body. His work with Rosenbleuth led Wiener to broader speculations about similarities between the communications and control systems in machines and those in natural and biological systems.

Natural Sciences director Weaver was also involved with a breakthrough book of the same era. In 1949, he co-authored the landmark text entitled The Mathematical Theory of Communication with Claude Shannon. The book remains essential to the understanding of information theory. Weaver’s introductory chapters are widely credited with making Shannon’s higher mathematical theories accessible to a more general audience.

Machine Learning

In the summer of 1956, the Rockefeller Foundation funded a milestone: the Dartmouth Conference on Artificial Intelligence. The five-week gathering engaged a group of leading researchers who were a veritable “who’s who” of computing innovators, including: John McCarthy, founder of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab; Marvin Minsky, who developed the idea of neuron nets and founded the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab; Claude E. Shannon, pioneer of Information Theory; and Nathan Rochester, developer of the IBM 701, the first general purpose, mass-produced computer.

The field was so new that mathematician John McCarthy had to invent a new term to help explain the concept of machine learning. In fact, the first known use of the term, “artificial intelligence,” was in the proposal that McCarthy (with co-authors Shannon, Minsky, and Rochester) submitted to the Rockefeller Foundation. At the time, the implications of the field were understood only by a handful of researchers. Even Weaver, an insider to applied mathematics, tempered his support for the proposal with restraint, although he authorized Robert S. Morison, Foundation Director of Biological and Medical Research, to act as he saw fit.

McCarthy requested $13,500 for a two-month conference, but Morison offered $7,500 for five weeks. As Morison explained,

I hope you won’t feel we are being overcautious but the general feeling here is that this new field of mathematical models for thought, though very challenging for the long run, is still difficult to grasp very clearly. This suggests a modest gamble for exploring a new approach, but there is a great deal of hesitancy about risking any very substantial amount at this stage.

Robert Morison to John McCarthy, 1955Robert S. Morison to John McCarthy, November 30, 1955, RAC, RG 1.2, Series 200.D, Box 26, Folder 219.

The significance of this new field, while murky to outsiders, was immediately evident to practitioners. IBM, Bell Laboratories, and RAND all lent support for their key researchers to attend.

The Birth of Artificial Intelligence

Today, the Dartmouth Conference remains widely acknowledged as the founding moment of artificial intelligence and has influenced research and development in mathematics, engineering, linguistics, computer science and psychology ever since. Its wide range of topics included complexity theory, language simulation, neuron nets, abstraction of content from sensory inputs, and the relationship of randomness to creative thinking.

Beyond subject matter, the Dartmouth conference signaled a major paradigm shift in how mathematical work would happen in the computer age. Essential to the conference was bringing researchers with disparate specialties together, freeing them from the strictures of teaching and publishing within their own subfields, and offering time and opportunity for collaboration and exchange of ideas and information.

The Dartmouth conference proved to be the high water mark of Rockefeller Foundation funding in the field of computer science. With military and corporate research increasingly driving the computer industry in the coming years, the Foundation’s funding became less and less necessary. But the seeds the Foundation planted were crucial to many later advances in the field.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Differential Analyzer,” 1932-1950. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, Massachusetts, Series 224, Natural Sciences and Agriculture, Subseries 224.D, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Electronic Computation,” 1932-1950. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, Massachusetts, Series 224, Natural Sciences and Agriculture, Subseries 224.D, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Dartmouth College – Artificial Intelligence – (Computers),” 1955-1957. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, General (No Program), Subseries 200.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Analog Study – (Economic Self-Sufficiency for Developing Nations) – (Holland, Edward P.),” 1958-1960. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, Social Sciences, Subseries 200.S, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Computation Center – (Morse, Philip M.),” 1956-1960, 1963. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, Social Sciences, Subseries 200.S, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Computation Center – Analog Study,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, United States, Series 200, Social Sciences, Subseries 200.S, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.