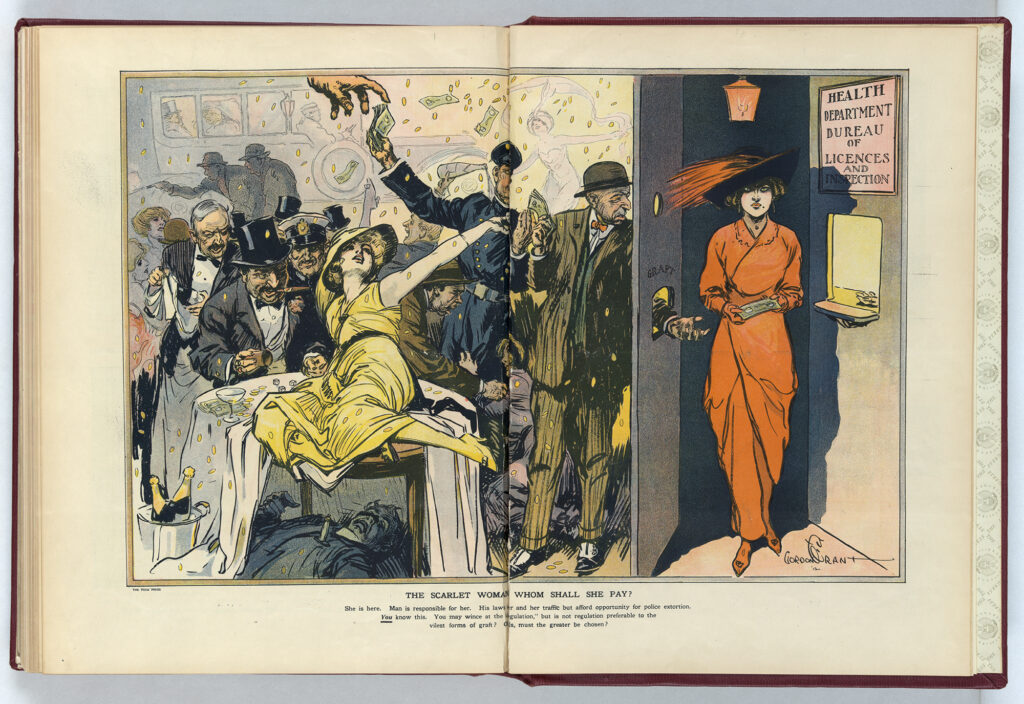

From 1911 to 1934, the Bureau of Social Hygiene funded research and sought to influence public policy on issues related to sex, crime, and delinquency. Additionally, the Bureau supported sex education by sponsoring the publication of materials related to sexual health. It then worked with state departments of health to disseminate these materials to the general public. But the Bureau’s leadership disagreed on how sexuality — and in particular, female sexuality — should be studied.

The era’s most progressive thinkers and activists — including the female head of the Bureau of Social Hygiene — argued that sexuality should be studied not only as a medical or criminal issue but as a sociological component of human life. On the other hand, most of the Bureau’s trustees felt that research along these lines would invite social backlash. This disagreement would ultimately shut the Bureau down.

Research in Service of Reform

The Bureau received contributions from a number of organizations, including the Rockefeller Foundation. Yet it depended largely on the patronage of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (JDR Jr.), who created the organization to address many of his own personal concerns and interests.

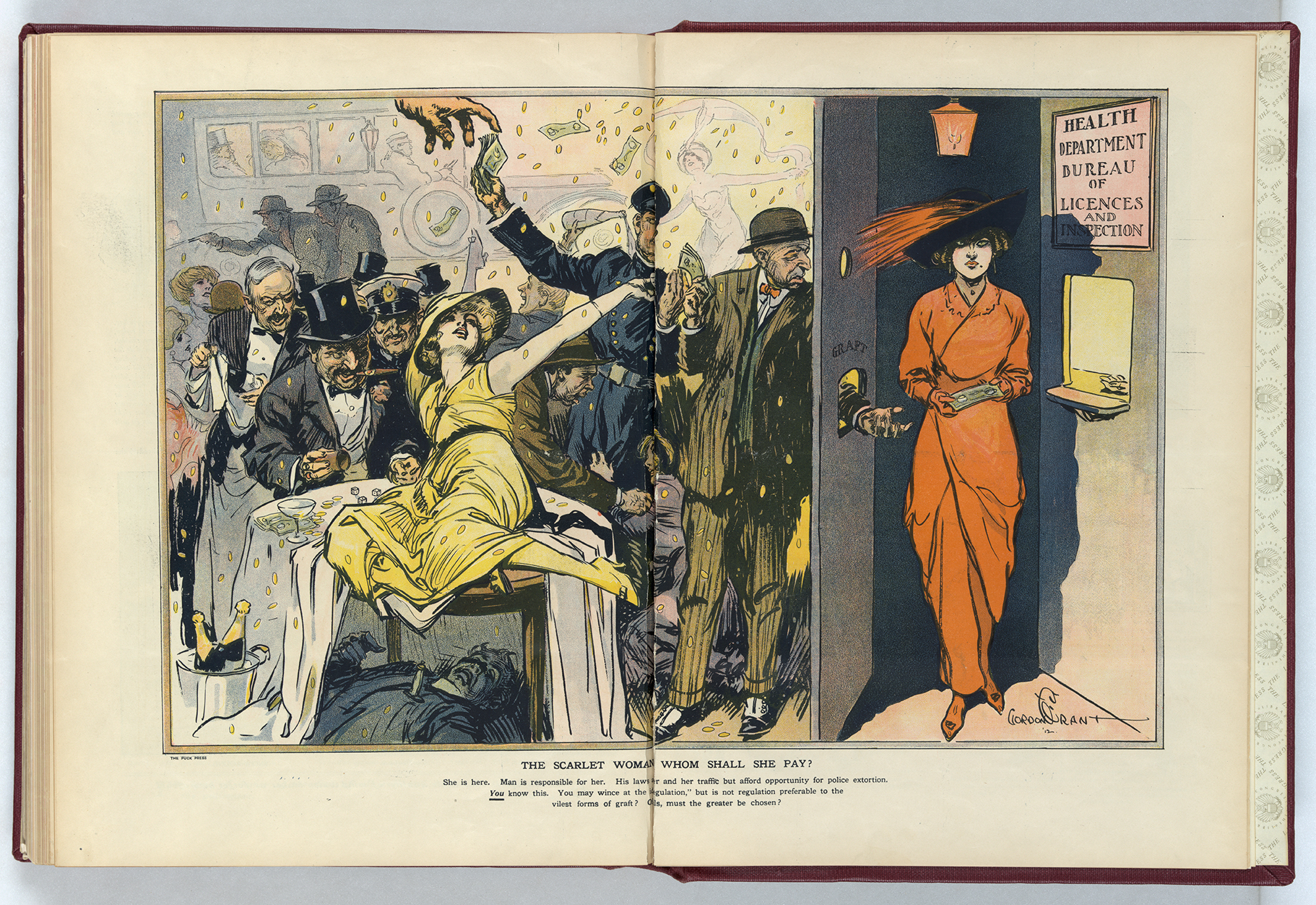

Rockefeller came up with the idea for the Bureau of Social Hygiene after he served on a 1910 grand jury investigation. The grand jury was charged with investigating “white slavery,” a commonly used term at the time for forced prostitution.

Consequently, frustrated with temporary public commissions that could only recommend governmental action, Rockfeller established a private body instead. He believed it could influence more directly what he viewed as the era’s greatest social ills. These included not only prostitution, but also corruption, drug use, and “juvenile delinquency.” “Rockefeller Way to Deal with Vice,” New York Times, January 27, 1913, pp.1-2.

The forces of evil are never greatly alarmed at the organization of investigating or reform bodies, for they know that they are generally composed of busy people, who cannot turn away from their own affairs for any great length of time to carry on reforms, and that sooner or later their efforts will cease, and the patient denizens of the underworld and their exploiters can then reappear and continue the traffic as formerly.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., “The Origin, Work and Plans of the Bureau of Social Hygiene,” January 27, 1913.

The Bureau’s earliest efforts concentrated on surveying the scope of prostitution in New York City and the “reform” of young women involved in the trade. It engaged Dr. Katherine Bement Davis, head of the New York State Reformatory for Women at Bedford Hills, to study the impact of prostitution on young women and come up with possible solutions. Davis, a member of the Bureau’s advisory committee from the beginning, was a well-known progressive-era reformer. She became New York’s Corrections Commissioner in 1914, the first female head of a major New York City agency.

Rooting Out “Problems”

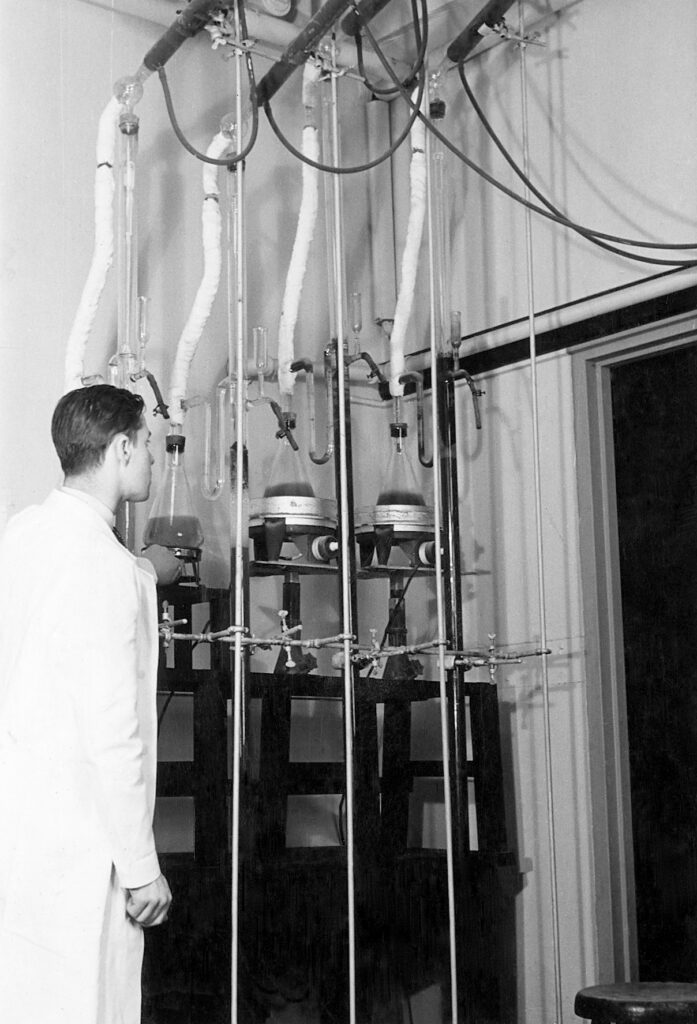

An additional $309,000 from JDR, Jr. enabled the creation of the Laboratory of Social Hygiene at the Bedford Hills Women’s Reformatory. The Laboratory operated from 1912-1918, testing female inmates for venereal diseases and making physiological and psychological assessments aimed toward defining a physical profile of the “criminal type.” Three years into its program, it added a hospital for “mentally delinquent women,” and sought to identify “inherited dispositions” for mental illness, temperaments that would supposedly lead a person to crime or promiscuity.

The Laboratory served as a clearinghouse for incarcerated females, scrutinizing them in order to discern whether or not they had the capacity for rehabilitation. Its findings helped the courts to fast-track placements in reformatories, mental hospitals, or prison, depending on how the women scored. Importantly, while the Bureau’s files show no evidence of sterilization as part of the Laboratory’s program, the Laboratory existed precisely during the brief window of time when New York State had a sterilization law in place. This law, passed in 1912, allowed sterilizations for “eugenic purposes.” Candidates included”inmates of State hospitals for the insane, State prisons, reformatories, and charitable institutions, and rapists, and convicted criminals in penal institutions.” The Supreme Court of Albany declared forced sterilization unconstitutional in 1918. The New York State Legislature repealed the law in 1920.

For the entire eight-year period that the law was in place, the State sterilized only one man. In stark contrast, the State sterilized 42 women.

Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Developing Data-driven Approaches

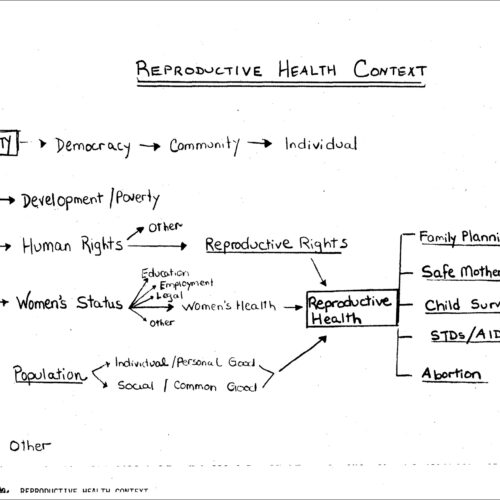

In 1917, Katherine Bement Davis became General Secretary of the Bureau of Social Hygiene, and her leadership transformed the organization. Davis believed that prostitution could not be fully addressed without a deeper understanding of human sexuality. To promote this understanding, Davis spent years advocating for more scientific research into human sexuality broadly construed. Her advocacy led to a partnership between the Bureau and the National Research Council that established the Committee for Research in the Problems of Sex.

The committee launched in 1921 and based its work plan on a proposal by Davis and Earl F. Zinn, to “undertake systematic comprehensive research in sex in its individual and social manifestations, the prime purpose being to evaluate conclusions now held and to increase our body of scientifically derived data.”Outline Presented by Mr. Zinn, Earl F. Zinn, undated, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), Rockefeller Family Boards, RG III 2 O, Box 7, Folder 50.

The proposed fields of research included the psychological and physiological aspects of the “sex instinct,” abstinence, masturbation, contraception, venereal disease and sexual relationships. Significantly, Davis and Zinn outlined an approach to research that would include not only medical and biological perspectives, but a sociological perspective as well.

…to increase our body of scientifically derived data.

Earl F. Zinn, 1921

Fear of Social Responses to Social Science

Yet to the dismay of both Earl Zinn and Katherine Bement Davis, throughout the 1920s, the Committee for Research in the Problems of Sex remained a relatively conservative organization controlled primarily by men trained in the medical sciences rather than the social sciences. Moreover, in addition to being generally uncomfortable with topics of human sexuality and fearing a public backlash for sex research, these committee members also expressed a distrust of the social sciences. Under their influence, the committee repeatedly funded studies that focused on topics of animal biology and sexuality while ignoring proposed studies on human sexuality.

Davis encountered significant obstacles from Bureau of Social Hygiene trustees who sought to distance the Bureau from its work in sex research and to redirect it towards topics deemed less controversial.

Another objection to having the Bureau of Social Hygiene go in for sex research on its own account remains to be considered. Sex research and the acceptance of new knowledge that may result from it presupposes a considerable brushing aside of certain prevailing taboos.

Leonard V. Harrison, “Comment made on Proposals Made by Miss Katherine Bement Davis for Reorganization of the Bureau of Social Hygiene,” Dec 6, 1927.

Bowing to internal pressures, Katherine Bement Davis retired on January 1, 1928. JDR, Jr. then reorganized the Bureau of Social Hygiene and appointed his close associate,Rockefeller Foundation trustee Raymond B. Fosdick, to lead it. The newly reconfigured Bureau became more deeply involved in the field of criminology, a longtime interest of Fosdick’s.

One of the arguments the trustees made against Davis’s proposed sex research work was that it would be too difficult to find a sufficient number of “normal” human subjects to study. In 1929, a year after her retirement from the Bureau (and drawing upon research conducted while at the Bureau), Davis published her comprehensive survey, Factors in the Sex Life of Twenty Two Hundred Women. Her work prefigures Alfred Kinsey’s similar work by nearly two decades. Kinsey’s headline-grabbing study, published in 1948, introduced the public to the unorthodox idea that human sexuality is a spectrum. And indeed it received a great deal of backlash. Interestingly, it was produced with support from both the Committee for Research on Problems of Sex (co-founded by Davis) and the Rockefeller Foundation.

The reorganized Bureau never really found its footing. Beginning in 1931, the Bureau of Social Hygiene planned its own demise by allowing all of its pending grants to expire. By 1933, with all grants concluded, the organization effectively ceased operations, although it did not formally dissolve until 1940.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “Bureau of Social Hygiene – Dr. Katharine Bement Davis – Study of Sex Life – Sex Research Work,” 1921-1927. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records; Rockefeller Boards – Series O; Bureau of Social Hygiene; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Bureau of Social Hygiene – John D. Rockefeller, Jr. – January 1913 Statement,” 1913. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records; Rockefeller Boards – Series O; Bureau of Social Hygiene; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Bureau of Social Hygiene – John D. Rockefeller, Jr. – Pledges,” 1911-1925. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records; Rockefeller Boards – Series O; Bureau of Social Hygiene; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Bureau of Social Hygiene – Publications,” 1906-1916. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records; Rockefeller Boards – Series O; Bureau of Social Hygiene; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Davis, Katherine,” 1925-1932. Bureau of Social Hygiene records; Administration – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Minutes,” 1917-1940. Bureau of Social Hygiene records; Administration – Series 1; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Research Council Committee on Sex Research,” 1927-1932. Bureau of Social Hygiene records; Projects – Series 3; Social Hygiene – Subseries 3_2; Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Yale University – Endocrinology,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records; Photographs – Series 100-1000; United States – Series 200; Medical Sciences – Subseries 200.A; Rockefeller Archive Center.

See Also

- Jessica L. Adler, “Health-Related Prison Conditions in the Progressive and Civil Rights Eras: Lessons from the Rockefeller Archive Center.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Leslie J. Harris, “The White Slavery Controversy, Women’s Bodies, and the Making of Public Space in the United States.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.