For more than 50 years, public television has been part of the lineup available to American viewers. As PBS, the broadcasting system that knits together dozens of local, independent stations, turns 50 in October 2020, it’s worth pausing for a moment to ask what makes public television different than the myriad other offerings available on screen. This story offers a brief look at the formative years of its legacy.

Ironically, its legacy is evidenced by the fact that, today, public television no longer seems quite so starkly different. Formats pioneered on public television, as well as some of its subjects, have been adopted by commercial networks. Another distinguishing feature has been that public television programs run without advertising. But these days, when subscription streaming services also offer content without breaks, that distinction has become less overt (if not less important). And yet, the presence or absence of commercial advertising isn’t the whole story.

Gallery: Selected TV Shows Developed with Foundation Support

At its core, public television has a different mandate than commercial broadcasting. Public television is defined by its commitment to present a diversity of perspectives and serve a variety of audiences without regard for profit. The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) describes itself as “treating audiences as citizens, not simply consumers.”

Origin Story: How Much Does It Cost to Do Your Best?

From the start, television broadcasting has been expensive — much more costly than radio. Making room for shows that didn’t earn a profit just didn’t make sense to the commercial networks. No matter how much the networks were pressured by educators, activists, and community groups, that needle remained nearly impossible to move. In 1961, in a speech to the National Association of Broadcasters, even the the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) lamented the industry’s pursuit of the lowest common denominator, calling commercial broadcasting “a vast wasteland.”

Programming that aimed to sell products was geared, inherently, to appeal to viewers with purchasing power. It did not attune its programming to the needs or viewpoints of other groups. That meant that America’s most under-resourced populations — whether the poor, ethnic and cultural minorities, the elderly, or young children — rarely saw people like themselves, let alone people speaking to them, on the air.

As Fred Friendly, president of CBS News until 1966 and then the broadcast consultant to the Ford Foundation from 1966-1980, put it, “television makes so much money doing its worst that it can’t afford to do its best.”Remarks by Fred Friendly on Public Television Station WTTW, Chicago, January 15, 1970. Ford Foundation Records, Catalogued Reports, Report #001889, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Building a Non-Profit Network

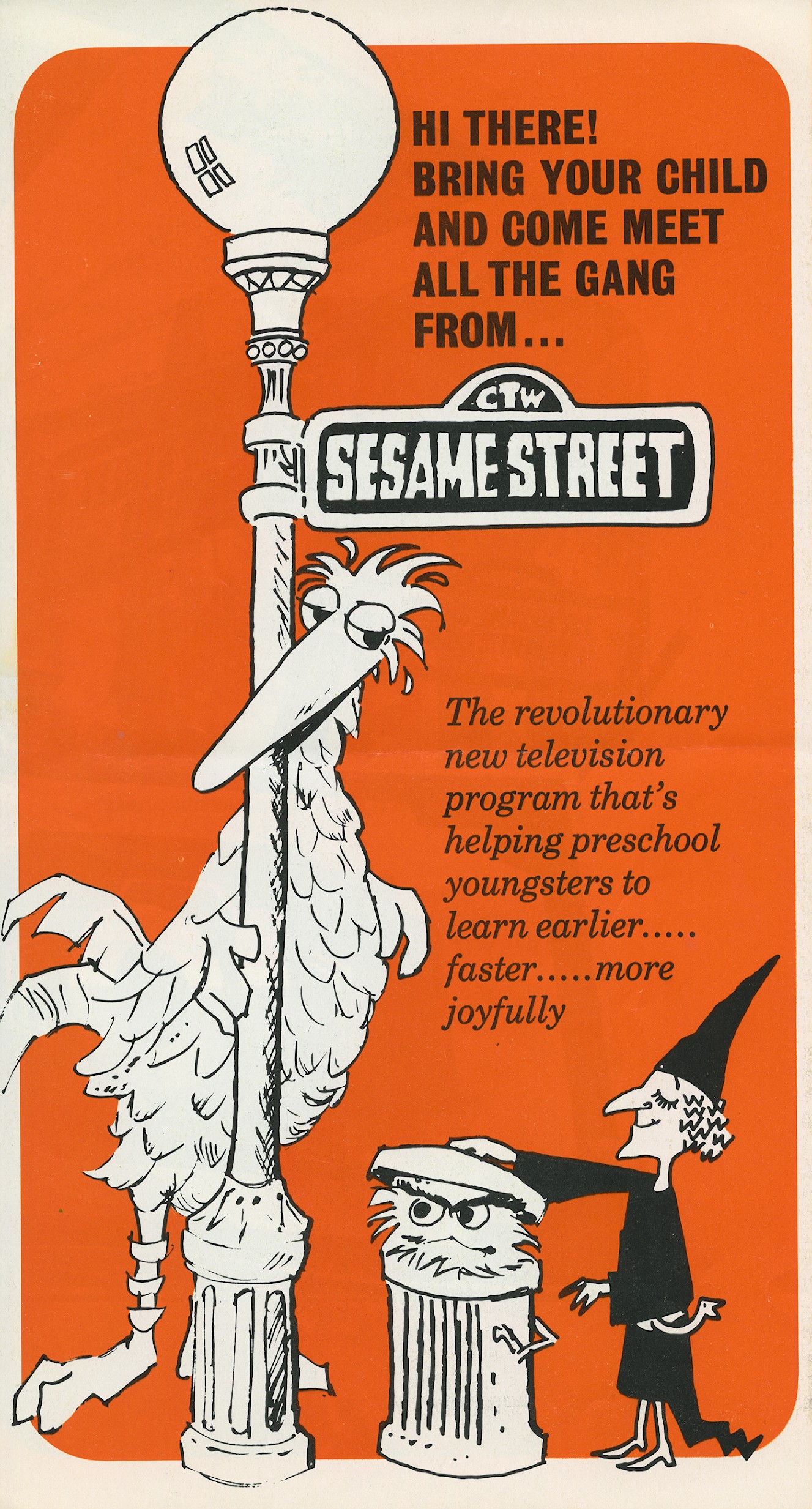

For more than two decades, from the 1950s through the early 1970s, foundation philanthropy helped public television get on its feet. The Carnegie Corporation organized the blue ribbon panel that called for federal legislation and resulted in the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. The Markle Foundation pivoted in 1969 from forty years of work in medicine to work in public television — seeing mass communications as a tool to serve a democratic society. That pivot brought Sesame Street to the world and revolutionized educational television for children.

The lion’s share of non-commercial television funding came from the Ford Foundation. Ford Foundation money established public stations, created a distribution network, provided technical training programs, and underwrote specific programs. By the time Ford concluded its public television grantmaking in 1973, it had spent $268 million on public broadcasting (roughly $1.6 billion in 2020 dollars).

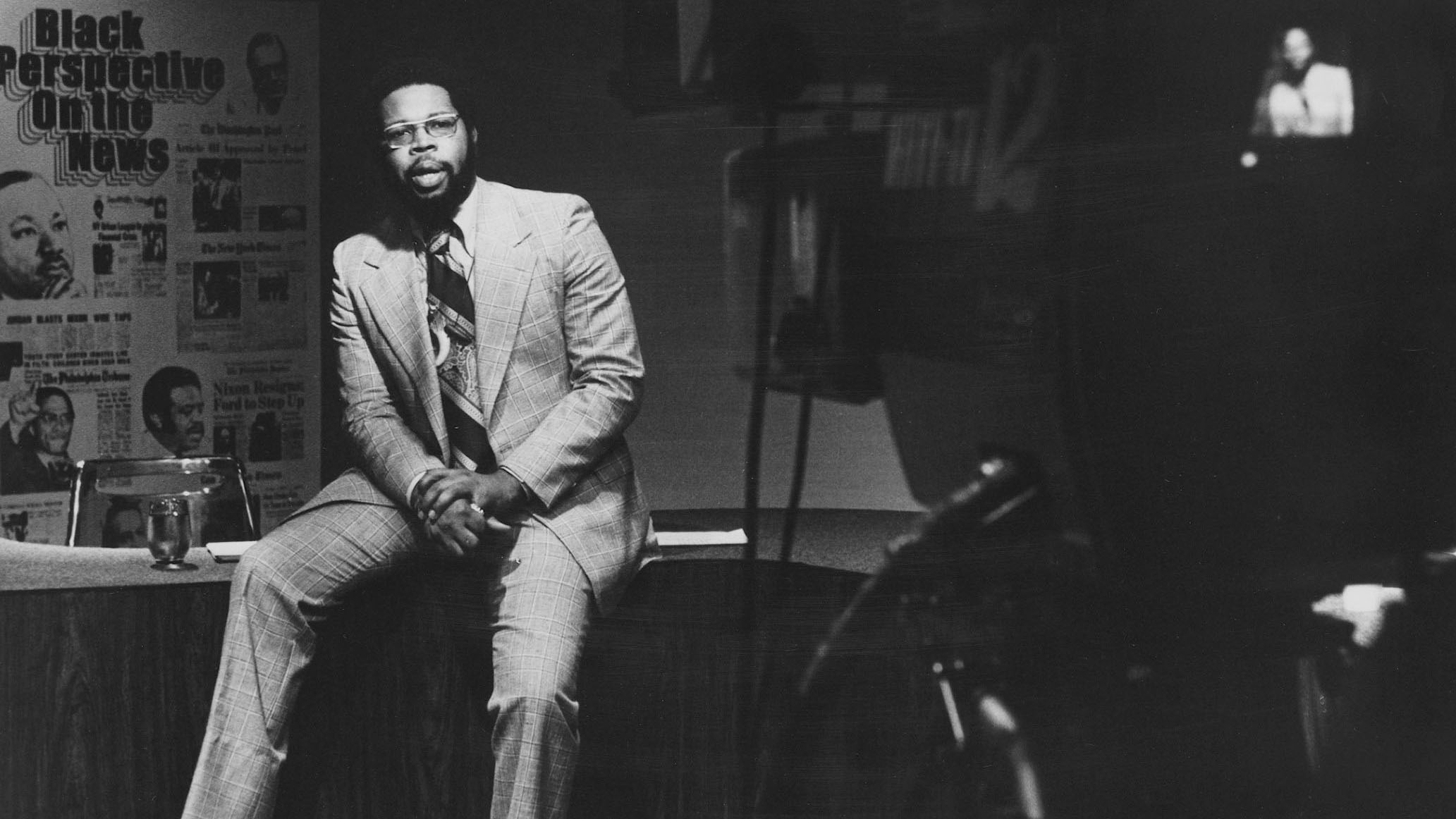

A Revolution in Representation

What began in the 1950s as an exploration of the educational potential of the new medium soon grew into a larger campaign. By the late 1960s, public television sought to serve the common good. Foundation philanthropists believed that providing a more representative portrait of the American people was a fundamental aspect of that mission.

Public television as we know it came of age in an era of social unrest and change. It emerged against the backdrop of the civil rights struggle and the War on Poverty. Grassroots causes, like the anti-Vietnam war protests, the youth movement, and the women’s movement, influenced its formative years. The hands-on involvement of foundation staff in supporting public networks and the programming they produced established a robust agenda characterized by diversity, experimentation in form and content, and social questioning.

A fair, balanced portrayal of racial, ethnic, and cultural experiences. Programming aiming to bring insight and understanding. Programming with a global focus. Programming created to narrow America’s social and economic divides, or at least shine a spotlight on abiding problems. These traits have come to seem inherent to public television. But in fact, they were carefully crafted and they evolved over the course of more than two decades, shaped and nurtured by philanthropic funders.

The attention to diversity that once set public programming apart has had proof of concept. Eventually, commercial networks found profit in appealing to a wider public. Nevertheless, the early years of public television still pose a question worth answering today: what is the difference between appealing to the public and serving the public good?

This post was updated in October 2020.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “A national noncommercial television service (Reports 001023),” 1963, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 1-3254, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Proposed financial support program for educational television stations (Reports 002806),” 1965, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 1-3254, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Educational Television and Radio Center (06700515),” 1967-1970, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants L-N, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Corporation for Public Broadcasting (06900013),” 1968-1969, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants C-D, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “637a. Public Broadcasting Corporation (PBC) and the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (ATT) agreement,” 1968, Ford Foundation records, Administration, Office of Communications, Press Materials, Record Group 1, Accessions 2017:062 and 2017:078, Press releases, Series 1, News from the Ford Foundation releases, No. 370-771, Subseries 2, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Markle Foundation – The Voters Channel (G90323) – PBS Initiative,” 1968-1998, Markle Foundation records, Accessions 1997-2008, Record Group 4, Accession 2000:016: Grants and General Files, Series 8, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Corporation For Public Broadcasting,” 1969-1978, 1980-1981, 1984, 1987, Markle Foundation records, Record Group 1-Record Group 3, Markle Foundation and Administration, Record Group 2, Accession 2, Subgroup 2, General Office Files, Series 2, Alphabetical Files, Subseries 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Children’s Television Workshop,” 1968, 1970-1971, 1974, Markle Foundation records, Record Group 1-Record Group 3, Markle Foundation and Administration, Record Group 2, Accession 2, Subgroup 2, General Office Files, Series 2, Alphabetical Files, Subseries 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Memos — Meade — Incl. Possible Original Proposal for Sesame Street,” 1967-1969, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Communications, Office of Communications, Program Staff Files, Fred Friendly Office Files, Series I, Subject Files, Subseries I.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Institute for Educational Development – Robert Filep,” 1970-1971, Markle Foundation records, Record Group 1-Record Group 3, Markle Foundation Programs, Record Group 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “KCET, Channel 28, Los Angeles, “Cancion de la Raza”,” 1968-1969, Ford Foundation records, Administration, Office of Reports, Photographs, General, Program, and Project Photographs, Series 3, Public Broadcasting (PB), Subseries 3 14, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Educational Broadcasting Corporation (07000132),” 1970-1971, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants E-G, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Related

Early Experiments in Public Broadcasting

The American public broadcast system as it exists today came out of years of work by organized philanthropy.