Emphasis in our time fails in helping people prepare for the end of life…

Hospice, Inc. Grant Proposal to the Commonwealth Fund, April 11, 1972Grant Proposal, “Development of a Staff and Base of Operations for Planning,” Hospice, Inc.,” April 11, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

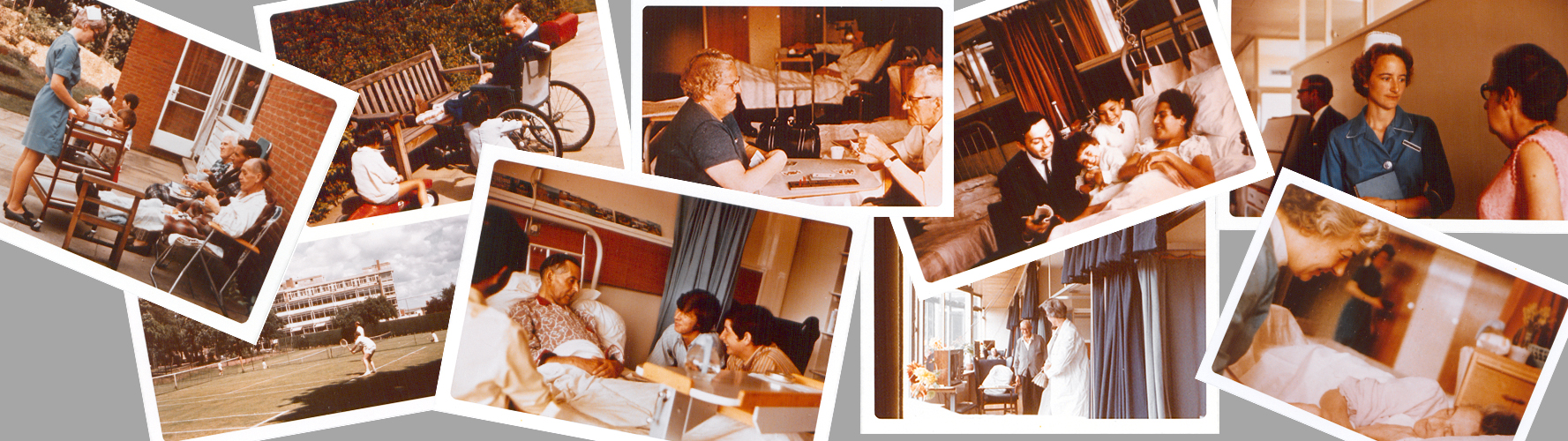

Today, the concept of hospice–palliative care for the terminally ill–is a standard component of American health care. With the goal of making a patient’s remaining days as comfortable, pleasant, and peaceful as possible, hospice services are a unique hybrid of nursing and social work. Practitioners focus not on curing disease, but instead on making the experience of disease more bearable.

According to the most recent 2019 report from the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), in 2017, 1.49 million Medicare patients benefited from hospice support.“NCPHO Facts and Figures,” 2018 Edition, Revised July 2, 2019, National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, accessed July 11, 2019.Yet until 1974, the modern hospice system was solely a British institution. (At that time, England maintained two modern hospice centers.)

What ultimately helped to bring modern hospice care to America was a two-year, $100,000 planning grant to Connecticut’s Hospice, Inc., provided by the Commonwealth Fund.

The Origins of Modern Hospice

Need death be a taboo topic? It is now, even for the medically trained.“Hospice: A New Model of Care for the Terminal Patient,” CRMP Newsletter III, No. 22 (August 21: 1972), Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

“Hospice: A New Model of Care for the Terminal Patient,” August 21,1972.

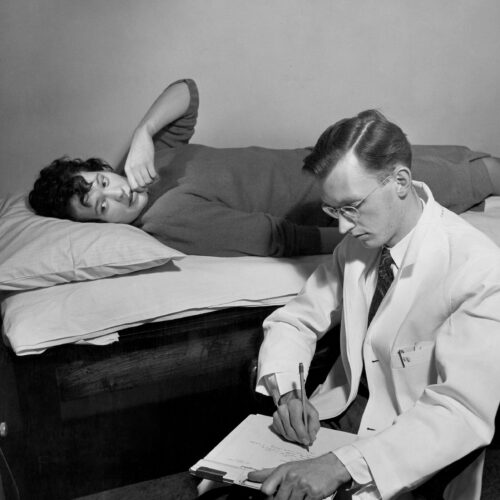

The term “hospice” historically refers to a home or location designed to care for those with a terminal illness. In the U.S. today, “hospice” is understood to represent an organized set of palliative care services, which may include a residential stay at a dedicated facility or in-home support. However, this model of end-of-life care wasn’t always the norm. In mid-century, medical professionals and nursing homes didn’t have plans in place, or didn’t know how to manage patient care for the terminally ill suffering from chronic degenerative diseases. Supporting a patient’s journey to death was often far more complicated than managing curative treatment.“Hospice, Inc.: Planning for Construction and Operation of a Model Facility for Dying Patients and their Families,” October 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In 1963, Cicely Saunders, a British nurse, physician, and medical social worker, whose practice focused on care for the terminally ill, gave a lecture on the subject at Yale University. Inspired by her words and work, Florence S. Wald, then Dean of the Yale School of Nursing, invited Saunders to become a visiting faculty member for 1965. This was an opportunity for Saunders to further develop her ideas about palliative care and share them with an American audience.“History of Hospice,” National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, accessed July 11, 2019.

In 1967, Saunders put her philosophy of a dignified death into practice, when she founded St. Christopher’s Hospice in England. St. Christopher’s was the first hospice to connect scientific research and pain management to a compassionate care approach to dying. Here, a patient’s remaining days were conceived of as being just as much about the life still lived as they were about the end to come.“Dame Cicely Saunders: Her Life and Work,” accessed July 11, 2019. Robert J. Glaser, Report of Meeting with Florence C. Wald, Edward Dobihal, and Morris Wessell, July 29, 1971, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.Saunders’ project soon became internationally known, and was a turning point for an American engagement with the modern hospice model.

Inspired by Saunders, Wald took a sabbatical from Yale in 1968 to work as a general duty nurse at St. Christopher’s.“History of Hospice.” Robert J. Glaser, Report of Meeting, July 29, 1971.Upon her return, galvanized by her experience, she joined with similarly minded Yale colleagues to create what became known as the Hospice Planning Committee (later this became Hospice, Inc.) to bring the St. Christopher’s model of hospice care to America.

Hospice, Inc.

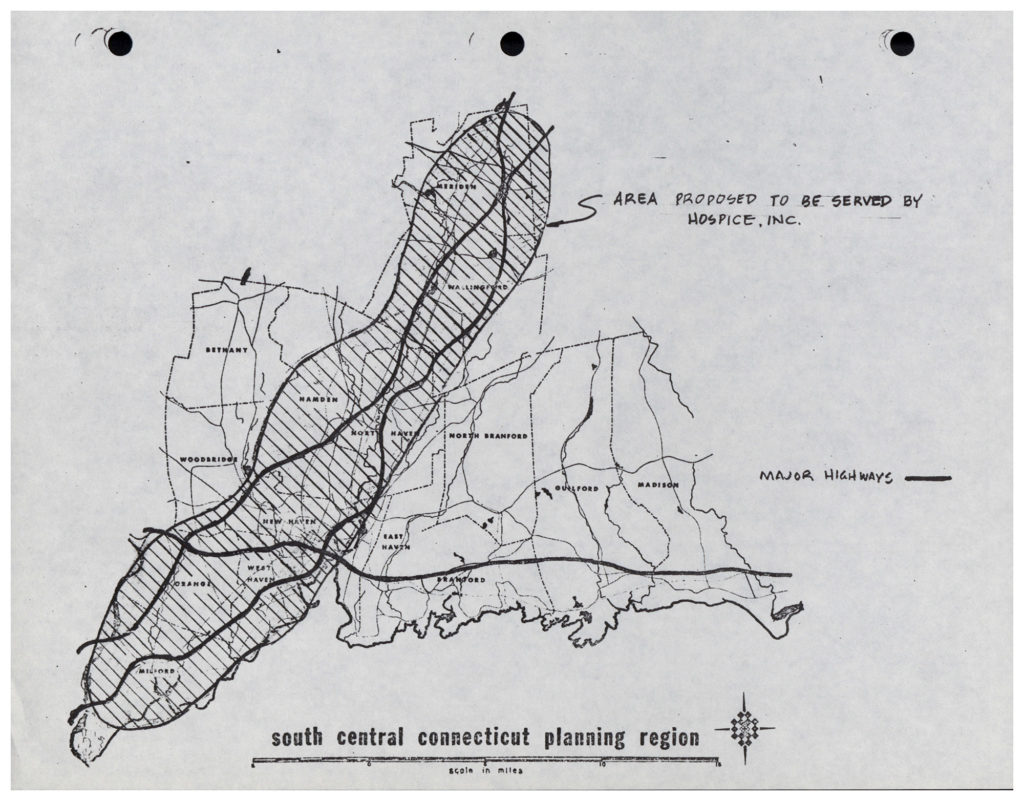

Hospice, Inc., was incorporated in 1971 in the state of Connecticut. Hospice, Inc., in part, aimed to move the needle on Wald’s statistic that, at the time, approximately 70% of the individuals who died in American health care institutions “receive[ed] care that [was] inappropriate and inadequate to help them come to the end of their living in a meaningful and gratifying way.”Florence S. Wald, “Statement by Hospice, Inc.,” on behalf of Hospice, Inc., 1970s, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Hospice, Inc. aimed not only to create a hospice program but also to build a training and research center that would serve as a “demonstration model for service” and a center for the investigation of “dying and bereavement.” Additionally, it planned to take on “other types of health care problems,” including studying the impact of quality of life on longevity, as well as extend its work to policy advocacy.Edward F. Dobihal to Robert J. Glaser, August 30, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Florence S. Wald, “Statement by Hospice, Inc.,” 1970s.

Wald characterized chronically ill patients of increasing debilitation as an “unwanted population,” with needs that fell outside the parameters of an acute treatment hospital but which nevertheless required specialized attention that was difficult to provide at home. Hospice, Inc. aspired to give this population dignity in death. As Wald put it, an American hospice would have an institutional emphasis on the dying being “loved and cared for…as important persons,” who could “find importance in the last days and moments of their [lives].”Florence S. Wald, “Statement by Hospice, Inc.,” 1970s.

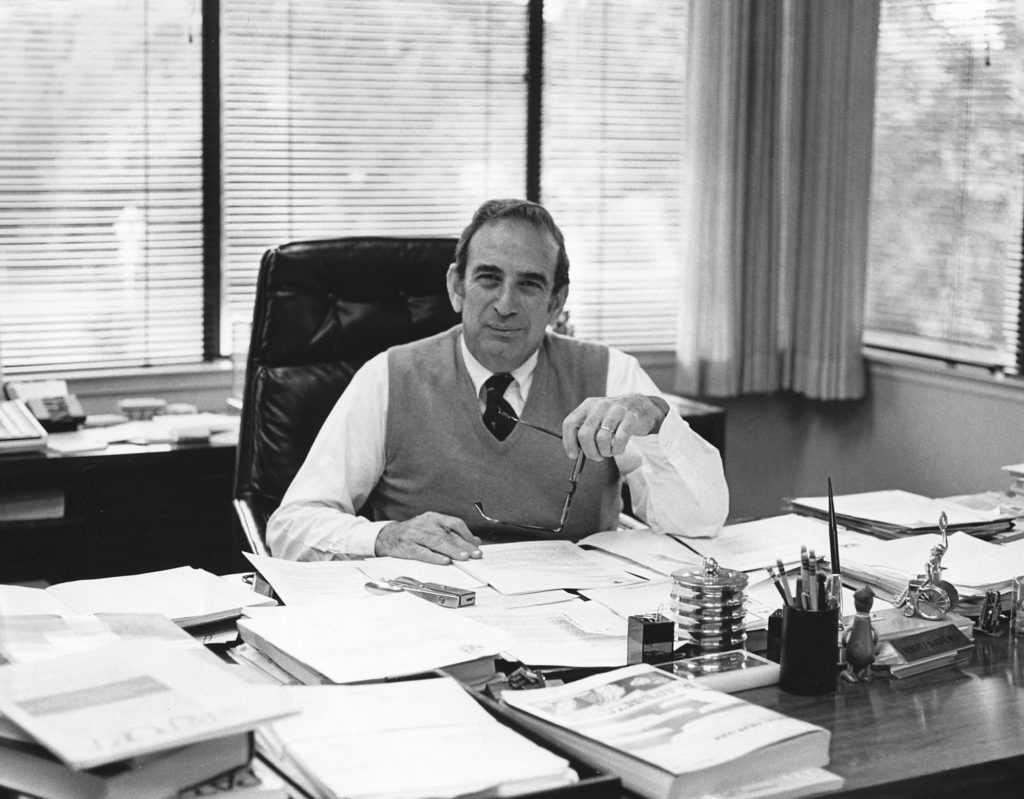

The Commonwealth Fund and an American Hospice

As it began to seek funding, Hospice, Inc. reached out to the Commonwealth Fund based on the Fund’s reputation for “developing innovative and useful modifications in the delivery of health care services.”Edward F. Dobihal, et al, December 1, 1971.The person at the Fund most likely to take an interest in the hospice concept was Vice President Dr. Robert J. Glaser. An internist by training, Glaser came to Commonwealth in 1970 following a five-year term as Dean of Stanford University Medical School. He brought to the Fund his expertise in medical education and his deep concern for patient care and clinical practice.

In July of 1971, at the suggestion of a Yale professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, Glaser met with a small group from Hospice, Inc., including Wald, Reverend Dohibal, and Dr. Morris Wessell, a Yale Pediatric Clinical faculty member who had been recruited to the organization’s executive committee.Robert J. Glaser, Report, July 29, 1971.

Central to the group’s pitch was the assertion that this new American hospice might very well launch a larger movement and serve as a model for other facilities. The Fund’s investment in this initiative, therefore, would be poised to make a bigger contribution than simply sustaining a small-town, Connecticut “service project.”Edward F. Dobihal, et al, December 1, 1971.

Glaser was intrigued. He was particularly impressed with the group’s holistic philosophy of palliative care, including its “clearly interdisciplinary approach.” But in his report from the meeting, he maintained that, despite the Fund’s interest, it could only extend financial support to the planning phase. Ongoing support would entail demands “far greater than we can meet.”Robert J. Glaser, Report, July 29, 1971.Furthermore, Glaser strongly suggested that the group obtain additional financial backing from two or three other foundations or organizations to strengthen its proposal to the Fund.Memo from W. Donway to Quigg Newton and Robert J. Glaser, March 6, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The American Hospice Takes Shape

In April of 1972, Hospice, Inc. formally presented its first proposal to the Fund: “Development of a Staff and Base of Operations for Planning.”

Guided by the philosophical bedrock of respect for the dignity of all “patients, families, [and] workers” involved in end-of-life care, Hospice, Inc. put forward its vision of an American hospice facility that would both ensure a dignified death for patients and help train and support professionals working in end-of-life fields.

Critically, Hospice, Inc. defined its hospice model as a community endeavor, with a team of patients, families, staff, volunteers, and medical professionals, each providing the other with “support and mutual understanding.” With collaboration among all parties involved in a patient’s physical, psychological, and social end-of-life care, hospice hoped that the terminally ill would then “be helped to garner strength for living and for doing what is important to them as life comes to a close.”

At the same time, Hospice, Inc.’s founders were not solely focused on humanitarian or ethical principles to make their case. They also underlined the practical, economic benefits of an American hospice. By removing the terminally ill from a hospital or nursing home, their proposal argued, hospice could help “curb skyrocketing costs of [health] care.”Hospice, Inc. Grant Proposal, “Development of a Staff and Base of Operations for Planning,” April 11, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

An Unexpected Hurdle

Though Hospice, Inc. received some early support in the form of a $10,000 loan and $22,080 gift from the Connecticut Regional Medical Program, unfortunately, by 1972, its leaders were coming up short in obtaining major financial partners outside of the Commonwealth Fund, as suggested by Glaser.“Hospice: A New Model of Care for the Terminal Patient,” CRMP Newsletter III, No. 22 (August 21: 1972), Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.Hospice, Inc. had requested support from several major foundations, but nothing materialized.Memo from W. Donway to Quigg Newton and Robert J. Glaser, March 6, 1972. Edward F. Dobihal to Reginald H. Fitz, September 19, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Margaret E. Mahoney to Edward F. Dobihal, Jr., January 12, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Desperate for the operational infrastructure required to mount Hospice, Inc.’s initial phases, Dobihal reached out to Glaser in May of 1972 to ask for a bridge grant of $20,532 for office and administrative supplies–an “urgent and immediate” need–to patch the enterprise through until a second, revised and full grant proposal could be submitted to the Fund. Edward F. Dobihal to Robert J. Glaser, May 22, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, RAC. Memo, May 4, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.Glaser agreed to provide $10,000 toward Hospice, Inc.’s interim staffing and administrative needs, which totaled more than $20,000, but only if the remaining balance of roughly $10,000 was supplied by another source.Robert J. Glaser to Edward F. Dobihal, June 9, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.As Glaser put it, “more than $10,000…might jeopardize consideration by our Board in November of your larger application.”Robert J. Glaser to Edward F. Dobihal, June 9, 1972.

By September 15, 1972, Hospice, Inc. had received over $10,500 through individual contributions. As a result, the Fund, in recognition of a “clear demonstration of effective support from local community sources,” provided the agreed upon $10,000, and the Hospice, Inc. team was able to move forward with their work.Edward F. Dobihal to Reginald H. Fitz, September 19, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center. “President’s Revolving Fund” memo, October 6, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, RAC.

The Fund and America’s First Hospice: From Vision to Reality

In November of 1972, Hospice, Inc. presented their second, revised proposal to the Fund’s board. Hospice, Inc. ultimately requested $143,300 to “combine highly-sophisticated [sic] medical management of the symptoms of the dying patient with an effective approach to the emotional crisis of dying as it affects the patient and his family.”“Hospice, Inc.”, October 1972.

Hospice, Inc. didn’t, however, want to waste time waiting for total funding support before getting to work. In their grant proposal, the organizers announced that in the interim they would start their Home Care Program, while making plans for the new facility.Hospice, Inc. Grant Proposal, April 11, 1972.

Ultimately, the Commonwealth Fund agreed to award Hospice, Inc. $100,000 to support a Connecticut hospice. The Fund’s grant underwrote a two-year planning period for Hospice, Inc. These two years gave the Hospice, Inc. team the freedom and flexibility to explore and develop criteria for admitted hospice patients and patient-care practice, and to test and implement organizational workflows without financial constraint.Quigg Newton to Edward F. Dobihal, Jr., November 15, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Dr. Robert J. Glaser, who had been the driving force behind support for the Hospice, Inc. proposal, left the Commonwealth Fund in 1972 to become President of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, where he maintained his personal commitment to the American hospice movement. In his new position, Glaser was able to award Hospice, Inc. $125,000 from Kaiser over two years beginning in 1974 to “develop community relations and for technical assistance.” Commonwealth Fund Memorandum, June 13, 1974, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Additional funding for the hospice project came from the Connecticut Regional Medical Program, the Van Ameringen Foundation, Inc., and the Max C. Fleischmann Foundation, alongside several smaller donors.Florence S. Wald to Henry Ittleson, Jr., October 20, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Quigg Newton to Julius Bergen, October 24, 1972, Series 18, Commonwealth Fund records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The First American Hospice

Connecticut Hospice was dedicated on June 29, 1980 in Branford, Connecticut. Among its more innovative features was an on-site preschool to foster intergenerational connections and add vibrancy to the community.Robert E. Tomasson, “At Hospice, Preschoolers Reach Out to the Dying,” The New York Times, December 27, 1987.

The Branford facility is still in operation as a hospice facility today and, thanks to the Commonwealth Fund’s initial support of Hospice, Inc., the modern hospice movement has grown to include over 4,500 hospice centers across the United States.“NCPHO Facts and Figures.”

Related

The “Insulin Gift”

In 1923, a wealthy philanthropist’s funding helped make life-saving treatment for diabetes available to patients and doctors.

The Long Road to the Yellow Fever Vaccine

The yellow fever vaccine developed in the 1930s has been used worldwide ever since. Creating it took years and cost several lives. Some thought it would never happen.

Photo Essay: The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission and the American South

Battling hookworm on rural farms laid the groundwork for a global public health system.

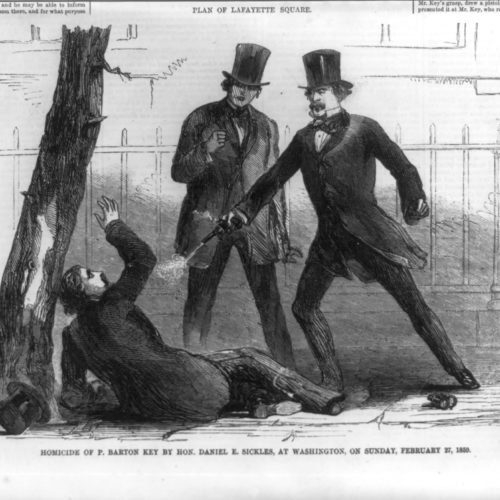

The Commonwealth Fund and the “Insanity Defense”: Unexpected Outcomes

Our understanding of the insanity defense relies on a book that was an unintended outcome of a Commonwealth Fund grant.