In the early 1960s, the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) made its first concerted effort to address school inequality when it launched a brand new social justice program, Toward Equal Opportunity For All (EO). One of the early goals of the program was to assist qualified candidates for college admission and help them move up the educational ladder. A centerpiece of this strategy was a grant to develop the Princeton College Summer Program, an early effort to identify qualified students and assist them in their preparation for college. The Foundation, however, quickly discovered that such a program did not really confront the structural causes of unequal opportunity and that economic inequality, manifested as substandard high schools in low-income neighborhoods, lay at the heart of unequal access to higher education.

An Initial Focus on Higher Education

Created in September 1963, the RF’s new EO program aimed to provide “our disadvantaged citizens better educational opportunities.” Early on, it mostly limited its grant-making to colleges and universities, a continuation of RF’s historic interest in higher education as well as building upon efforts in the early part of the century by the Rockefeller-initiated General Education Board (GEB) to support historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).“Excerpt from ‘Plans for the Future – A Statement by Board Members of the RF, Adopted at Board Meeting, September 20, 1963,” Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.29, Series 900, Program and Policy – Equal Opportunity, EO-1 Through EO-7, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Early EO grants went to the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), a large umbrella organization for HBCUs, as well as Emory, Duke, Vanderbilt, and Tulane (four colleges that had previously received GEB funding) to recruit and provide financial aid to qualified African American students.Leland DeVinney, “Toward Equal Opportunity For All: A Summary Report of the Foundation’s Efforts In This Program, 1963-1974,” 12-14, Rockefeller Archive Center; Elizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History,” 62-65, Richard Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

RF leaders (perhaps too optimistically) believed these programs would slowly integrate higher education, foster economic opportunity, and erode the country’s larger culture of racial discrimination.

Few within RF believed that improving primary and secondary schools — the very sites of the “root causes” of the problem — aligned with the Foundation’s strategy at the time. EO Chair Leland DeVinney, for example, noted that the “inferior quality of primary and secondary schooling available to the bulk of Negro children” would make it difficult to find large numbers of qualified candidates for college scholarship and recruitment programs. He nevertheless thought it a mistake to lower the Foundation’s high academic standards for the sake of supporting a greater number of more disadvantaged, and lower-achieving, students.Leland DeVinney to Kenneth Thompson and George Harrar, June 24, 1963, “RF Aid to Negro Education in the United States,” Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.29, Series 900, Program and Policy – Equal Opportunity, 1959-1973, Rockefeller Archive Center.

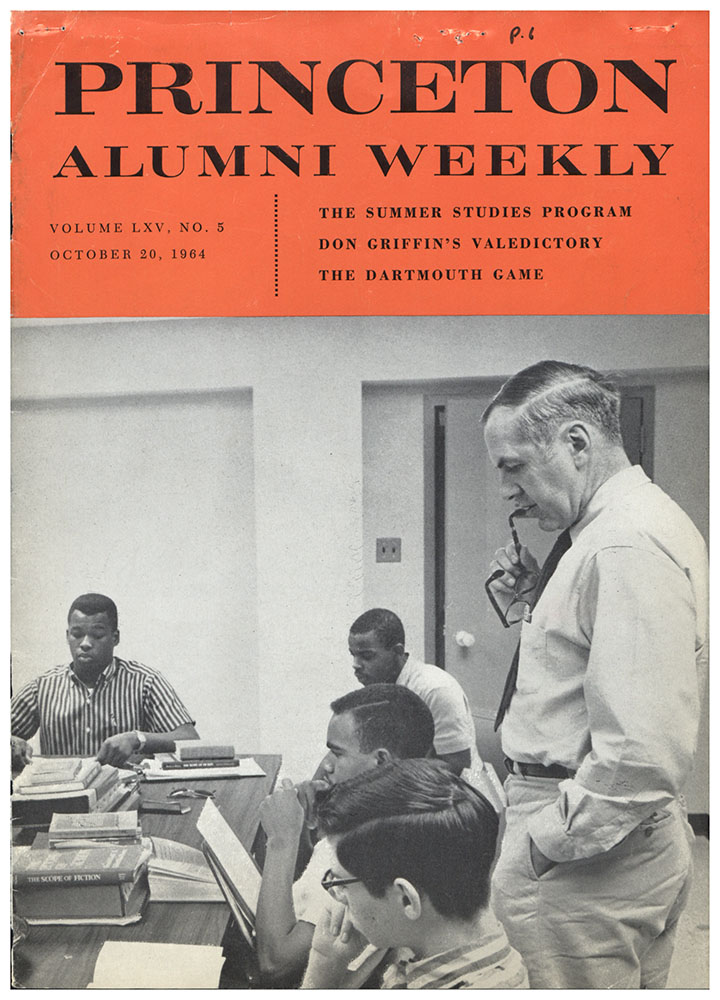

In December 1963, the Foundation awarded a grant for a promising new initiative, the Princeton College Summer Program (PCSP), after DeVinney started hearing reports from college recruiters that they could not find qualified minority students for admission.

DeVinney believed the recruiters were not looking hard enough, and Princeton officials — most notably J. Merrill Knapp, Dean, and Robert Goheen, the university’s president and an RF trustee — agreed.Romney, 108; LCD Interview with J. Merrill Knapp et al., November 11, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.The PCSP proposed to address this problem by preparing, and helping colleges identify qualified minority students for university admission.

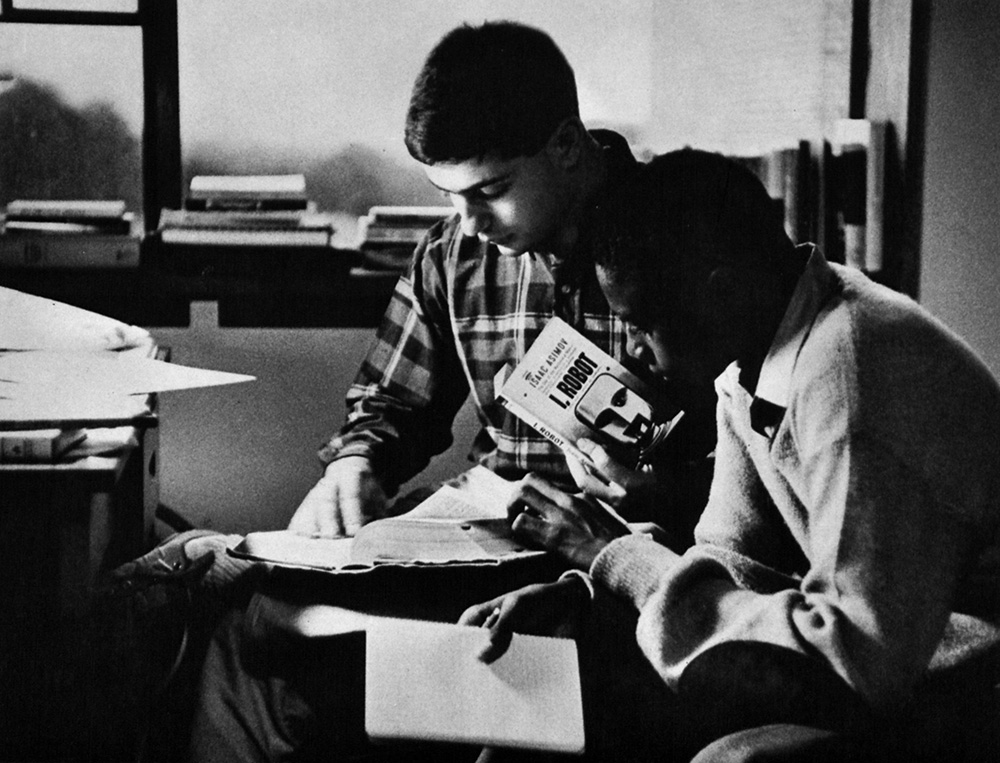

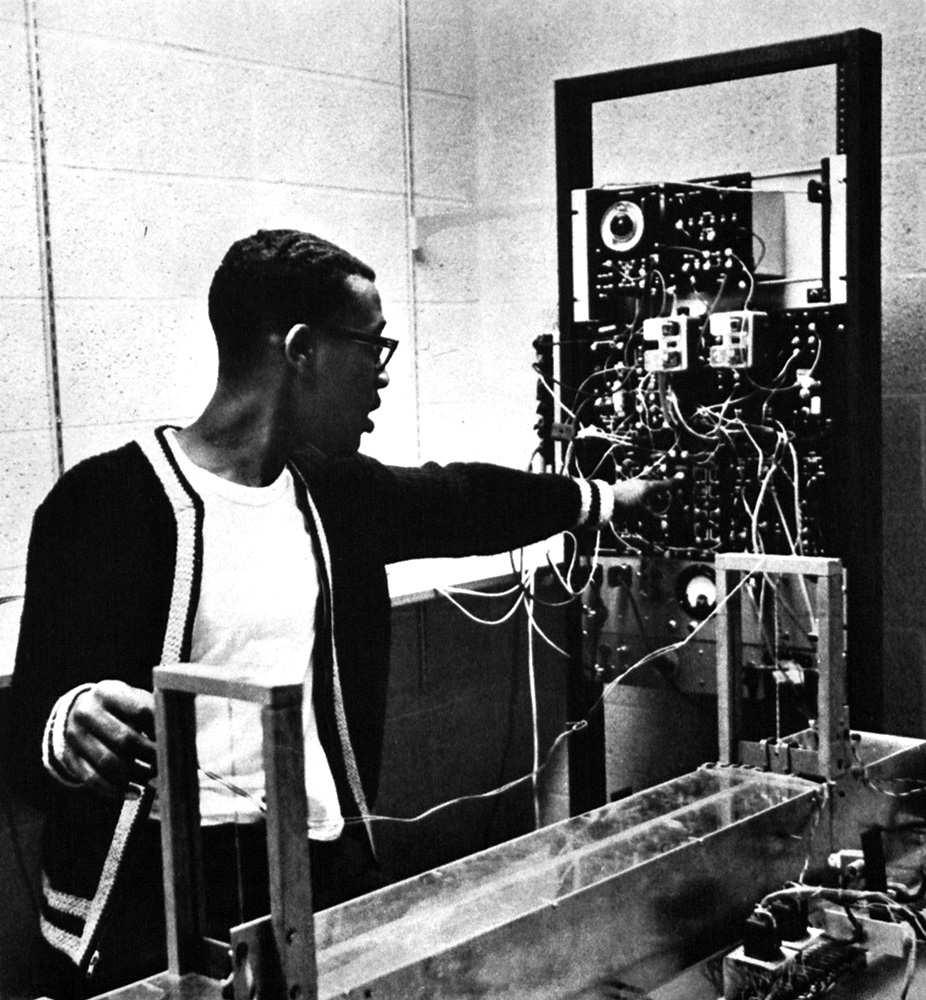

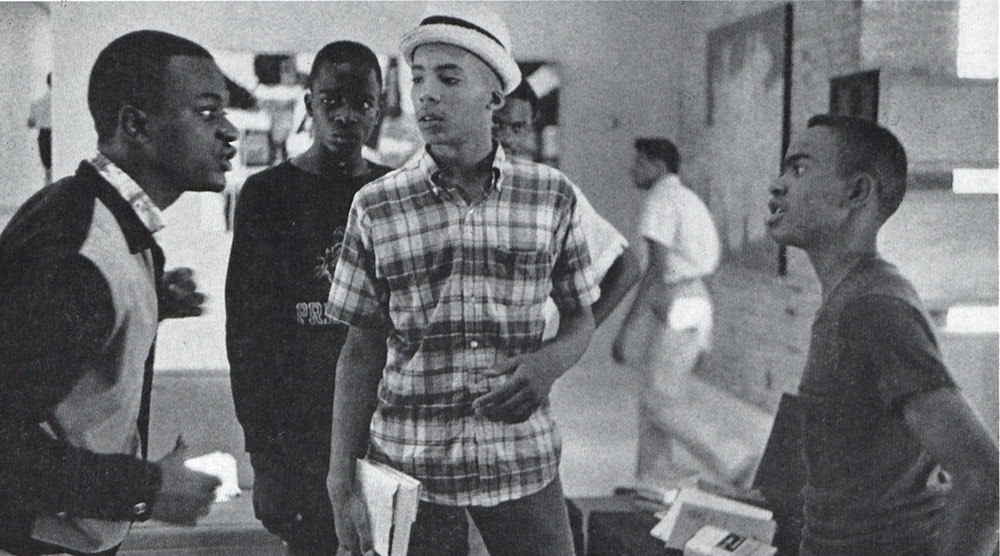

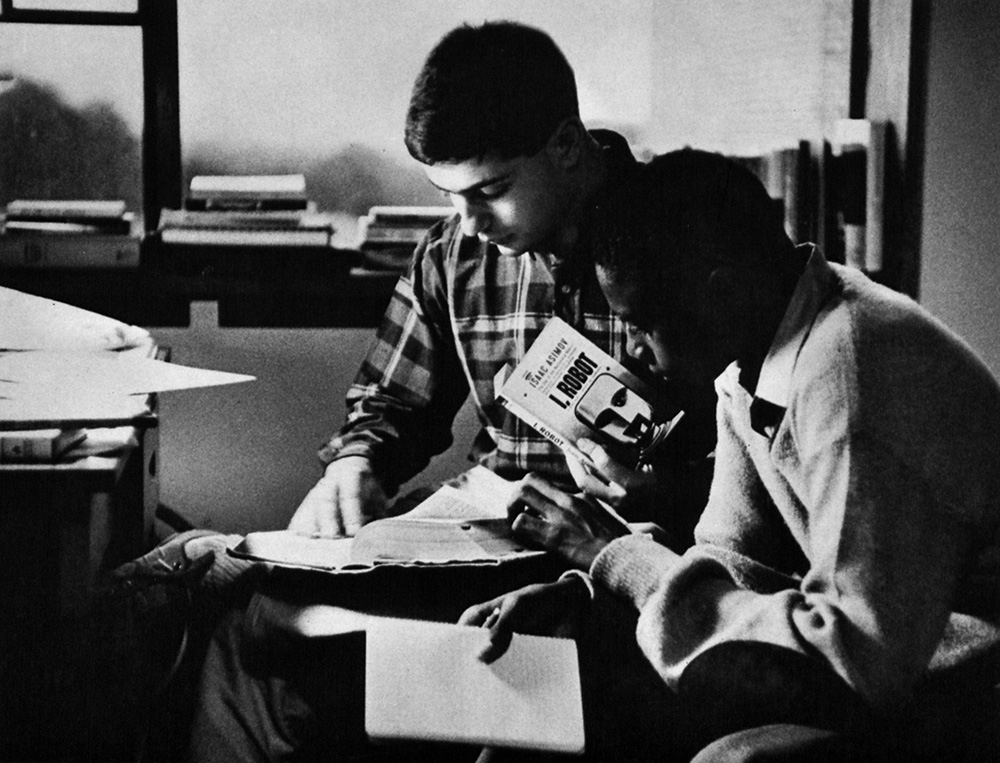

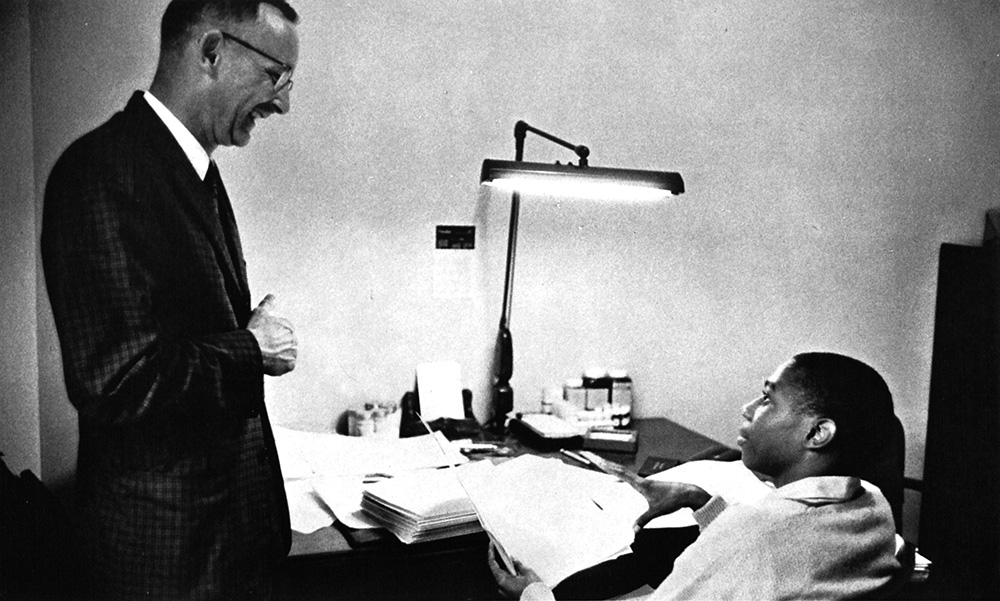

Initially funded with an RF grant of $150,000 over five years, the PCSP selected 30 to 50 students described as “youngsters who had shown good but not fully realized potential,” from low-income schools across New Jersey.“Remedial Summer Programs for High School Students,” 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center. The program was designed and implemented by Princeton undergraduates and professors, as well as local high school teachers, and featured math, science, reading, and writing curricula, as well as off-campus field trips and organized social activities. After the program, students received follow-up academic counseling and college application sessions from PCSP staffers.Sheldon Judson and Charles W. McCracken to R.F. Goheen, “Interim Report of Princeton Summer Studies Program,” for the Period January 1 through September 30, 1964, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center; Romney, 129-30.

We have demonstrated that boys can be transferred from ‘center city’ to the ‘greenhouse’ of Princeton.

Sheldon Judson, “Princeton Cooperative School Program: An Interim Report, September 1965,

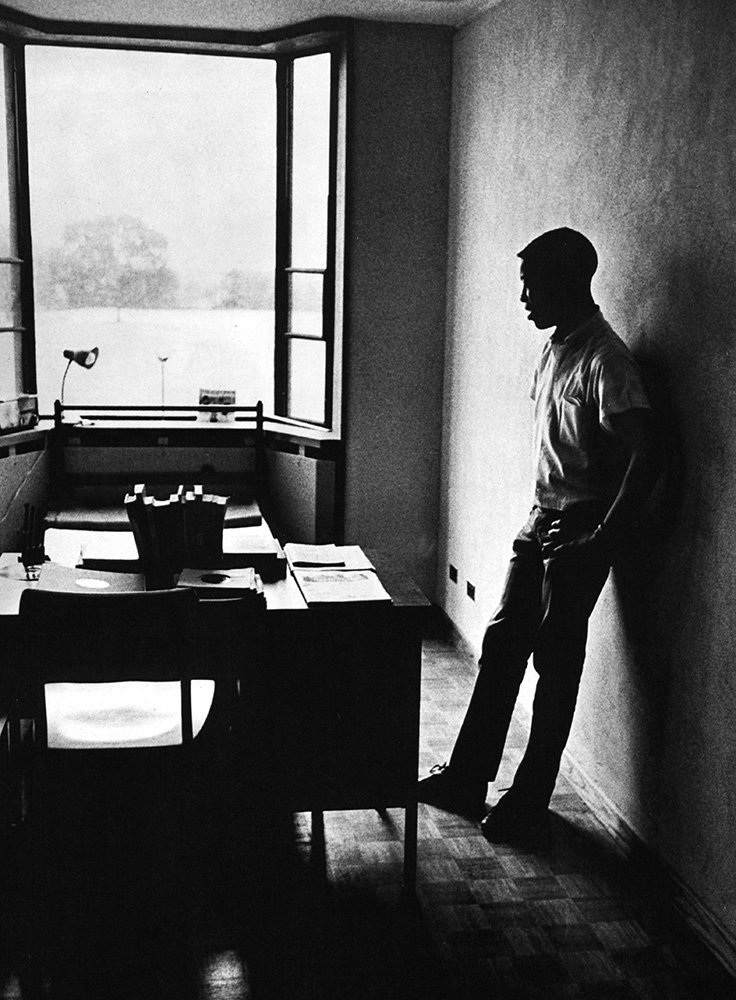

The PCSP hoped to cultivate in students a love of learning and academic discovery. The program promised to “free students and faculty alike from ordinary academic routines, notably from such machinery as examinations and grading” and instead emphasized independent study, small discussions, and experiential learning. These activities, PCSP leaders reasoned, would help students gain the confidence and motivation to “to acquire new skills or strengthen weak ones.”Sheldon Judson and Charles W. McCracken to R.F. Goheen, “Interim Report of Princeton Summer Studied Program ,” for the Period January 1 through September 30, 196, Rockefeller Archive Center.

How to Measure Success

By the main metric on which it measured itself, college admissions, the PCSP was quite successful. There were forty students in the program’s original cohort. Thirty-six received college acceptances and two-thirds graduated college, a slightly higher percentage than the national average. These trends continued in successive years: no fewer than 71% of students in the PCSP’s first five cohorts entered college.“A Survey of Retention and Attrition in the Princeton Cooperative School Program (Upward Bound), 1966-1975,” Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

But these statistics were in some ways misleading. Initially, the PCSP selected students solely on the basis of academic merit — grades, teacher recommendations, and a personal interview.Sheldon Judson and Charles W. McCracken to R.F. Goheen, “Interim Report of Princeton Summer Studies Program,” for the Period January 1 through September 30, 1964,” Rockefeller Archive Center.

When the Princeton program began receiving federal funding in 1966, its selection criteria changed. The new federal funding came through a program called Upward Bound, established in 1965 as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Johnson’s programs pumped billions of federal dollars into new education, job training, and community action programs through a new national bureau called the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO).

Tasked with alleviating poverty, not only with helping select individual students apply to college, Upward Bound mandated that the PCSP accept candidates from more economically-disadvantaged backgrounds. Under these guidelines, only students from families earning below a certain annual income level would qualify for the program.

As a result of this change, the program began accepting more students from lower-income brackets, and from different (less well-funded) school districts. Though the RF continued to provide the PCSP with some small funding until 1971, the vast majority of program participants after the late 1960s were identified using the government’s antipoverty guidelines. Romney, 40, 114-120; R.F. Goheen to George Harrar, January 3, 1967, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

A Changing Strategy

Accepting these students revealed to the PCSP the effects of subpar secondary schooling. In response, the program began devising initiatives that might counteract the structural inequalities of the US public school system.

For a while, both the RF and PCSP had believed these interventions were unnecessary. Instead, they hoped the Princeton experience would transform students, returning them to their local schools as role models capable of elevating their classmates’ levels of achievement and sparking a more engaged academic environment.R.F. Goheen to George Harrar, January 20, 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

As one PCSP report claimed:

The possibility that excellence of education (as represented by Princeton) and problems of the urban center…can be brought in direct combat to mutual benefit is perhaps the single most important fact that has emerged in the last two years.Sheldon Judson, “Princeton Cooperative School Program: An Interim Report,” September 1965, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

By the early 1970s, however, the PCSP had changed its tune. Analyses showed that the program had not had the same effect on the federally-funded Upward Bound students as it had on their earlier counterparts. For example, one report noted that 80-90% of Upward Bound students entered college, but only about 40-50% ultimately graduated, a lower percentage than among the program’s initial participants.

While there were many reasons for this decline, the report noted that there were “several negative social forces operating over which we had no control,” most of which stemmed from conditions fostered by the increasingly chronic poverty of inner-city neighborhoods in the early 1970s, including violence, drug use, and “urban high schools where the educational quality was rapidly declining.”“A Survey of Retention and Attrition in the Princeton Cooperative School Program (Upward Bound), 1966-1975,” Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The lesson was clear: college prep was not a one-size-fits-all solution to educational inequality. To further broaden the pool of candidates applying for college admission –and improve their chances for success once admitted – the PCSP would have to stage more direct interventions into improving local high schools.

But was the PCSP capable of doing this? Untangling the web of issues plaguing inner-city schools seemed far beyond the capacity of a single college prep program. Nevertheless, PCSP officials tried. Program staff began exploring ways to integrate PCSP-type programming into local communities and schools. PCSP leaders proposed having program staff attend educator workshops, discuss school policies with administrators, and perform outreach to local parents and civic organizations. In all, the PCSP hoped these grassroots efforts would help combat at least some of the factors that had created high schools that produced students unable to thrive in the PCSP (and college) setting.“Remedial Summer Programs for High School Students,” February 25, 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center; “Princeton Cooperative School Program Annual Report,” October 1969; “Princeton Cooperative School Program: Work Program Narrative,” October 27, 1970, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

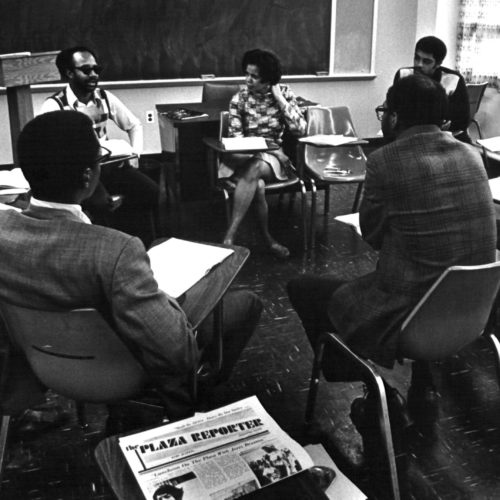

Reflecting this shift, the PCSP removed the word “college” from its name and started to call itself the Princeton Cooperative Schools Program. It also began to establish community centers staffed with local teachers and guidance counselors for PCSP students, and convene meetings between Upward Bound officials and local teachers to discuss the larger challenges facing urban education.“Princeton Cooperative School Program Annual Report,” October 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

These efforts signaled a clear shift in the PCSP mission. It was simply not enough run a college prep program for a few dozen students each year. A far greater impact could be made by confronting structural inequality within the country’s neighborhood school system.

This evolution proved instructive for the RF. Watching the PCSP grapple more concertedly with public school reform helped the Foundation identify gaps in its own EO programming.

Just as the PCSP began working at the neighborhood level, the RF formally established a community schooling component for its EO program that supported local experiments in public education. Moving forward, the RF, much like the PCSP, would focus far less on college acceptance and more on addressing the chronic poverty and segregation that fostered inferior schooling at the neighborhood level.

But this would not be an easy road. The PCSP suspended its operations after the summer of 1976 and, looking back, lamented its inability to address more fully the challenges its Upward Bound students brought to the classroom.

Aren’t you pretty hard on yourself?” one federal official asked the head of the PCSP after reading its final program report. “You point out the principal difficulty: an educational program…became a social program and took on the societal problems as well as the educational ones.John Rison Jones, Jr. to Earl Thomas, April 28, 1977, Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

By the time the PCSP closed down, the EO program had similarly confronted the challenge of addressing a broader range of “societal problems” beyond access to higher education. The experience of the Princeton program helped the Foundation embrace this more ambitious strategy.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “United Negro College Fund, Inc.,” 1962-1966, 1972, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, General (No Program), Subseries 200.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “The United Negro College Fund (Reports 011086),” 1967, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 9287-11774, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Papers for Equal Opportunity workshop on affirmative action,” 1961-1991, 1970-1982, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.9-SG 1.13 (A83-A87), (A83), Subgroup 1.9, United States, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Earlham College – Remedial Education – (Upward Bound),” 1966-1971, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.2, Series 100-253, International and United States, United States, Series 200, General (No Program), Subseries 200.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Community Development — Upward Bound and Community Action,” 1968, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Leadership Development Program, Administrative Files, Northeast Region, Series 1, Northeast Region Administrative Correspondence, Subseries I.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Related

Can Data Drive Social Change? Tackling School Segregation with Numbers

In the years before Brown v. Board, a philanthropic fund hoped research and data would turn the tide on attitudes toward segregation.

Photo Essay: Supporting Minority Enterprise in the late 1960s

In 1968, the Ford Foundation began to make social investments using a new tool borrowed from the for-profit world, the Program-Related Investment.

“Investment Philanthropy” Investing for Social Good, a Century Ago

An early twentieth-century foundation tried using its endowment to support for-profit projects that also would achieve a social goal.

Supporting Economic Justice? The Ford Foundation’s 1968 Experiment in Program Related Investments

How the largest US foundation began supporting market-based projects in the late 1960s.