A New Philanthropic Tool

In 1968, the Ford Foundation board of trustees authorized a $10 million experiment. Using grant funds and investment assets, Foundation staff identified and funded private-sector, for-profit projects that might encourage minority entrepreneurship and African American economic empowerment. These market-based initiatives ranged from agriculture and manufacturing to housing and community development.

This project used a new tool called the Program-Related Investment (PRI). It was conceptualized to broaden the scope of recipients that philanthropic funds might reach, and has since become a widely available philanthropic tool. Looking at the origin story, we see that the 1968 experiment yielded mixed results.

The Civil Rights Movement was Always about Economics

Philanthropic strategists were not the first to identify economics as a leverage point for achieving social justice. The economic dimensions of racial inequality in the United States had been a core focus of African-American-led racial justice campaigns since Marcus Garvey promoted economic black nationalism in the 1920’s. Then, after World War II, African Americans were largely excluded from that era’s economic boom because of redlining and workplace discrimination. Activists responded with boycotts to exhibit the collective economic power of an overlooked population.

The civil rights movement’s political demands would have the effect, many organizers hoped, of opening up equal access to American economic life through jobs, commerce, and housing. As the philanthropic sector struggled to understand how it could assist with such major issues, John Simon of the Taconic Foundation and Lou Winnick at Ford worked to imagine new ways that their organizations, and other foundations, could have a broader impact with their relatively limited grant dollars .

Economic Assimilation

In the mid-twentieth century, wide-ranging ideological stances emerged in the racial justice field, from Black Nationalism to Marxism. By 1968, many mainstream African American activists and foundation professionals began to share similar, more assimilationist, movement goals.

One typically shared goal was the better integration of disadvantaged populations into the broader American economy. All of the groups involved hoped to make capitalism work so that African Americans would not find themselves at the bottom of the system, but rather could rise within it. As Massachusetts Senator Edward Brooke put it, African Americans should be the “owners and managers” not just “employees and laborers.”Jet. Volume 32, Number 18 (August 10, 1967). Johnson Publishing Company, ISSN 0021-5996. See also Robert E. Wemes and Lewis A. Randolph, Business in Black and White. American Presidents and Black Entrepreneurs in the Twentieth Century. NYU Press (2009).

John Simon and Lou Winnick Create the PRI

Taconic president John Simon, a Yale law professor, wrote the legal framework in federal tax regulations that would allow philanthropic foundations to give loans to for-profit entities. Beginning in 1967, Simon convened foundation leaders to persuade them to consider pooling their respective resources into a financial intermediary called the Cooperative Assistance Fund (CAF).The Rockefeller Brothers Fund kept detailed records of CAF from the very beginning. See Rockefeller Brother Fund records, Record Group 3: Projects (Grants), Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

While contributing operating funds to help run CAF, the Ford Foundation was developing its own PRI program to run in-house. In the summer of 1968, National Affairs Director Lou Winnick circulated an information paper among the Foundation’s board of trustees. In it, he first laid out the economic argument for implementing a “Program-Related Investment Account (PRIA).” The experiment promised cost effectiveness through new programs “in minority enterprise, housing and conservation where financial aids other than outright grants could achieve philanthropic goals.” This meant that “the philanthropic dollar could be stretched further to do double, triple, or even higher multiple duty.”The 1968 information paper was summarized in a 1970 Ford Foundation report, “Information Paper. Program Related Investments. Two Years Later. A Report on Progress and Problems in PRIA,”(1970), 2. Ford Foundation records. Catalogued Reports, Report #002129, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Some foundation staff believed that the economic projects would lay the groundwork for other, more far-reaching structural changes:

“Minority enterprise appears to have a unique potential for restructuring the ownership and leadership patterns of poverty areas in ways that cannot be achieved by better jobs and housing. The future may, of course, prove our view to be wrong.”Harvey Shapiro, “The Difficult Art of Mixing Philanthropy and Business. An Assessment of a Grant to the Cooperative Assistance Fund,” Project Evaluation, Division of National Affairs (1972), 42. Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Report #002211, Rockefeller Archive Center.

…the philanthropic dollar could be stretched further to do double, triple, or even higher multiple duty.

Lou Winnick, 1968

New Beneficiaries, New Practices

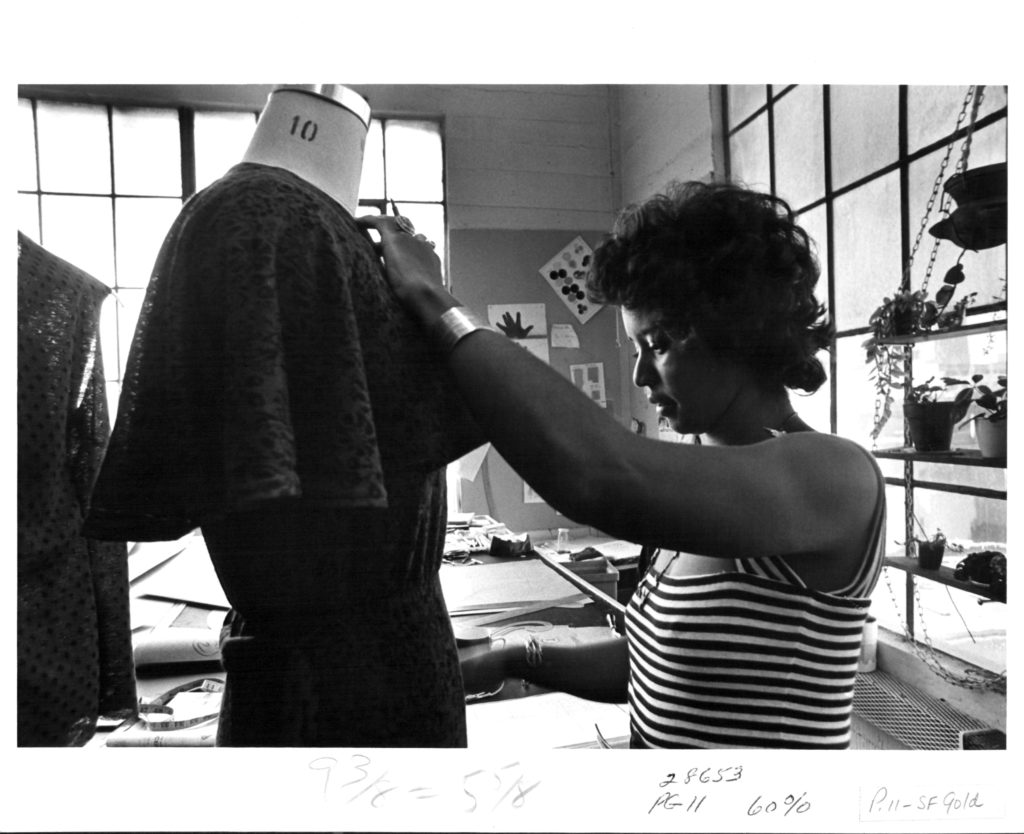

The PRI program promised to expand the range of philanthropic beneficiaries. That’s because foundation assets that would previously only have been able to support nonprofit organizations would now be able to fund for-profits such as farms, factories, construction companies, radio stations, housing cooperatives, and commercial centers. Foundation staff hoped that these funds would kick-start black-owned businesses and fuel community economic power.

Thus, this approach also assumed that PRI-funded projects would produce revenue, which could in turn attract other investments from private banks and capital funds. Ford’s PRI, Winnick thought, could “[spring] loose the resources of banks, insurance companies and other private investors not hitherto prominently associated with our grant-making operations.”Winnick, “Information Paper” (1968).

By acting as a lending partner in the private sector, the Ford Foundation could also model more just financing practices. The 1968 Annual Report described the multiplier effect it aimed to have:

“[This] demonstration of new credit practices […] might stimulate banks and other major sectors of the credit economy to respond more broadly to new public needs.”Ford Foundation Annual Report (1968), Rockefeller Archive Center.

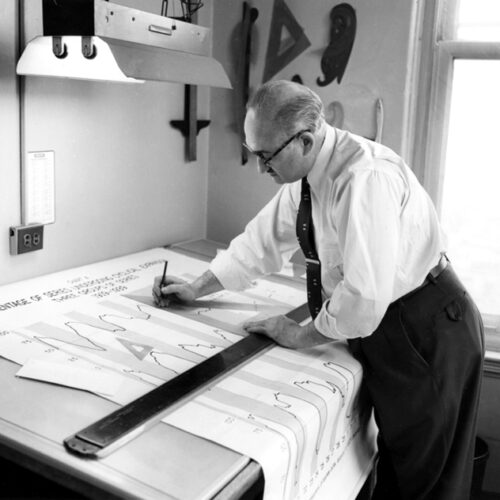

The Ford Foundation board approved Winnick’s proposal and allocated $10 million for the experiment. With the trustees’ blessing, Winnick and his National Affairs colleagues chose a first cohort of PRI beneficiaries, in fields as wide-ranging as agriculture, apparel manufacturing, and urban retail. Ford staff approached the task steeped in optimism about the structural change they hoped to stimulate.

Putting the Idea into Practice

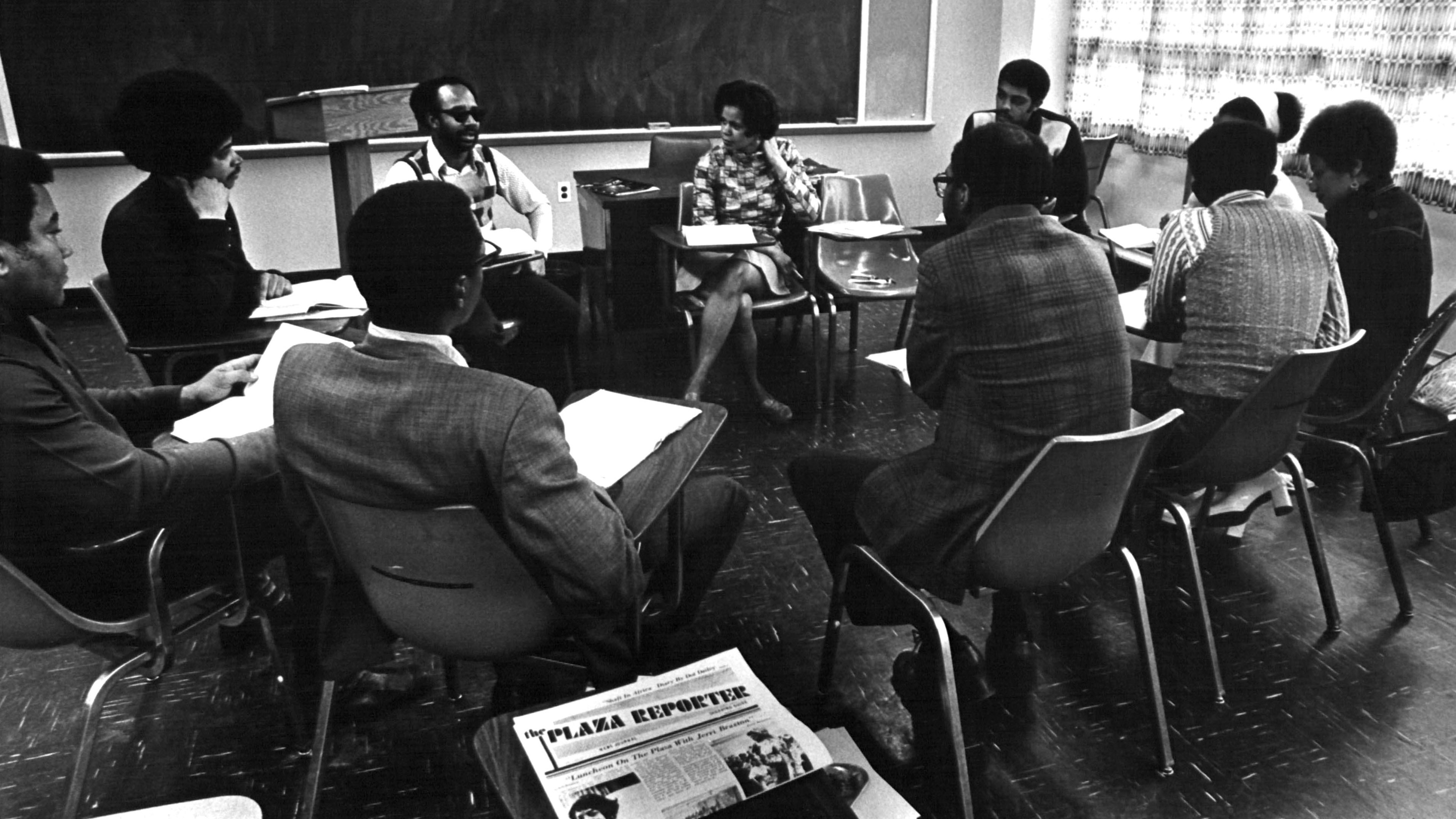

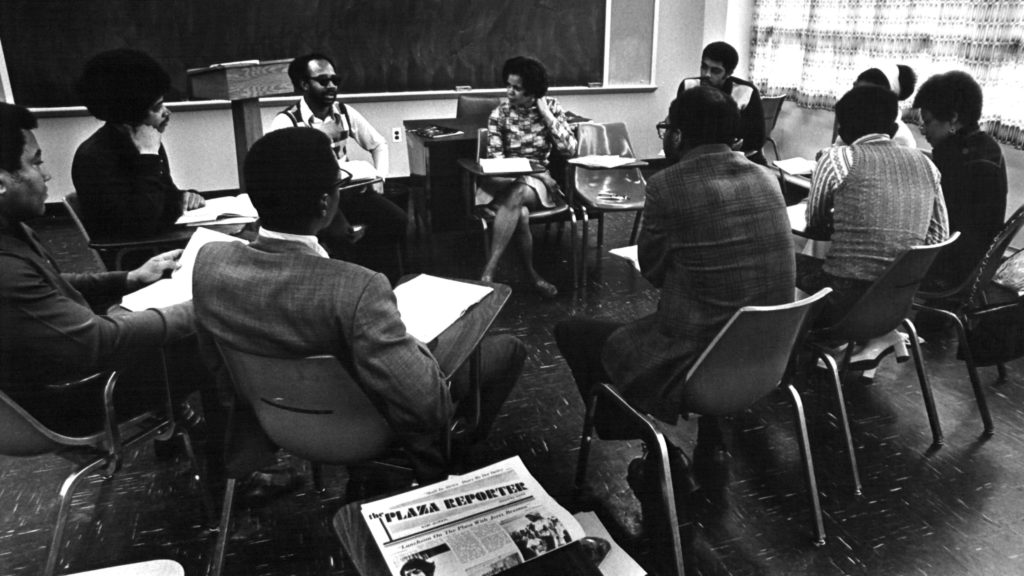

Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA.

Civil rights activist and Philadelphia organizer Reverend Leon Sullivan, who had started a national network of job training centers, led one of the first projects in Ford’s PRI portfolio. Since the early 1960s, he had been mobilizing community donations to form a local investment pool in Philadelphia, which would later become the Progress Movement community development corporation and its Zion Non-Profit Charitable Trust.Sullivan’s “10-36 Plan” asked congregants and community members to commit ten dollars a month for thirty-six months. This formed the capital basis for housing and other for-profit projects. The Zion Non-Profit Charitable Trust exists today as the Leon H. Sullivan Charitable Trust.

In 1968, the Ford Foundation loaned Sullivan’s group a half-million dollars in preferred stock to help build the Progress Plaza shopping center, the country’s first shopping center owned and run by African Americans.Stephanie Dyer, “Progress Plaza. Leon Sullivan, Zion Investment Associates, and Black Power in a Philadelphia Shopping Center” in Michael Ezra, ed., The Economic Civil Rights Movement. African Americans and the Struggle. Routledge (2013), 144-162.

The project garnered national attention, even as Ford staff were signing the paperwork. Presidential candidate Richard Nixon made a campaign stop at Progress Plaza in his effort to court African American votes. Progress Plaza fit right into the “black capitalism” concept Nixon promoted on the campaign trail.

Initial Results

Despite political and foundation support, Sullivan and his backers immediately encountered difficulties. For one, local retailers failed to meet the minimum of $1 million in assets that insurance companies required for a good business credit rating, and so were rated extremely poorly. While the shopping center itself garnered healthy investment, the poor credit ratings of individual merchants hampered efforts to draw additional investors to support small businesses. This made it difficult to populate the center with local merchants. To keep the project financed, within a couple of years white-owned chains were brought in. As historian Stephanie Dyer has shown, many local businesses had difficulties competing with the larger chains and couldn’t hang on for long under these circumstances. Dyer, “Progress Plaza” (2013).

But in the end, Leon Sullivan’s leadership and community support made Progress Plaza a success. Ford’s PRI was, of course, just one part of this bigger story. But the loan served as a sort of vote of confidence from an establishment organization and helped Sullivan’s project get over the finish line in those early years. As of this writing, African Americans have continuously owned the shopping center, and Progress Plaza was recently celebrated as an historic Pennsylvania landmark.

Investment Success, but No Silver Bullet

Like many new endeavors, the PRI may have promised more than it could fulfill. Initial assessments of the first Ford portfolio were mixed, as some businesses went under or failed to pay back loans. One statistic nevertheless stands out: Ford Foundation PRI commitments had the multiplier effect of an estimated five outside dollars amassed for every one Ford dollar invested.Shapiro, “The Difficult Art of Mixing Philanthropy and Business” (1972), 42.

Business investment couldn’t do it alone, though: PRIs often complemented rather than replaced foundation grants. While PRIs increased the pool of resources devoted to advance social goals, grants were still necessary to pay for technical assistance, leadership development, training, and other non-recoverable costs. And it was immediately apparent that PRIs cost much more to administer than grants did.

Should Foundations be in this Business at all?

Some financial analysts wondered, were philanthropic professionals even the appropriate administrators of PRIs? In 1970, Ford hired Bruce Classon, an outside evaluator from the financial field, to take a look. His review was a scathing assessment of both the wide-ranging projects and Ford staff expertise. He joked that the PRI program as Ford conceived it “would dictate staffing by a peculiar breed of super-loan officer who would be equally at home with catfish as with steel.”Bruce Classon, “Review of Program-Related Investments. A Report in Five Parts,” (1970), 8. Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Report #004510, Rockefeller Archive Center.In Classon’s view, the National Affairs division had no such superheros on staff. This deficit in expertise seemed all the more concerning given the leadership role that Ford played in its PRI partnerships. Even when the Foundation contributed less than other investors, Ford garnered an out-sized leadership role:

“The Foundation has won not only the title of respected crusader and pioneer, but also finds itself in a position of fiduciary responsibility heightened even more by virtue of the rest of the confederation not wanting to risk a move until Ford takes the first step. “Classon, “Review of Program-Related Investments” (1970), 22.

Taking a look at the projects themselves, Classon’s review characterized the operations of the PRI-supported enterprises with phrases such as “poor accounting,” “financial reporting extremely inadequate,” and “horrendous financial condition.” Through a purely financial lens, early PRIs seemed to be bad investments, although it is possible, of course, that this analysis was itself influenced by racial stereotypes and mistrust.

Furthermore, PRIs could not solve deep-seated, racist practices outside of the program’s purview. Other foundation programs soon sprang up, hoping to address housing segregation, fair access to credit, and anti-discriminatory hiring practices.

Too much risk — or not enough?

…we’re now becoming bankers.

Vivian Henderson, 1973

Finally, an ideological issue remained unresolved from the perspective of the philanthropic foundation. Did the PRI represent a financially risky endeavor for the cause of social justice or, by adopting private sector mechanisms, was it a capitulation to the economic structures that contributed to the injustice in the first place? Put simply, was the PRI too risky or not risky enough? Should Ford continue to work within the system or challenge the system itself?

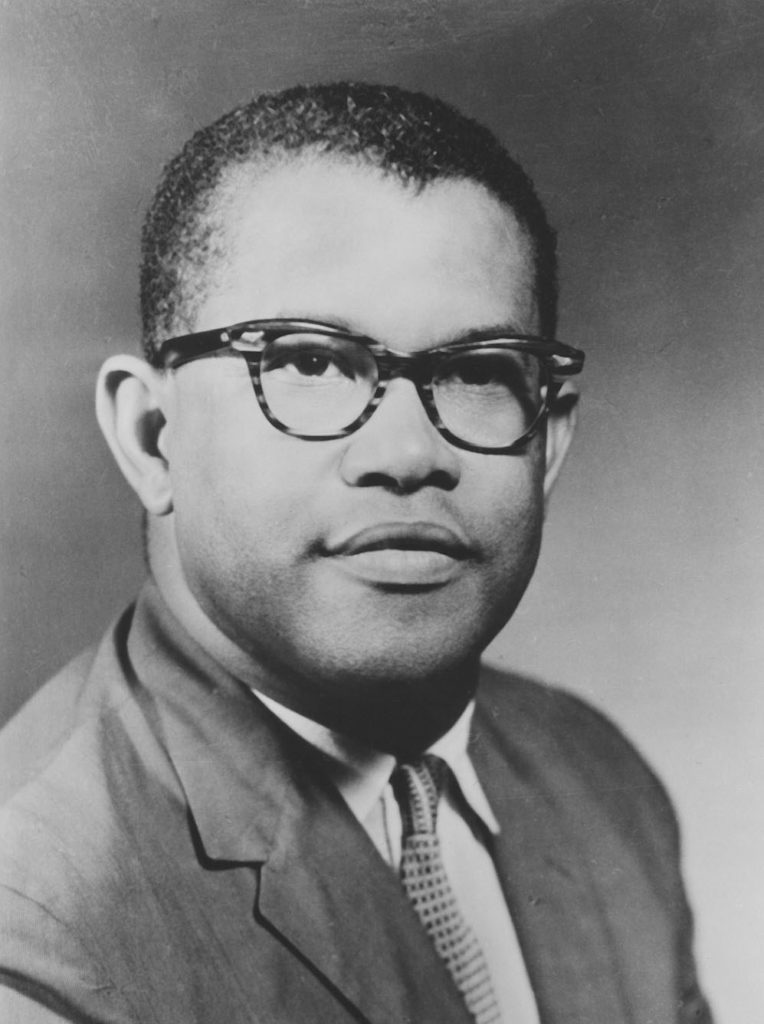

These questions remain– with perhaps increased relevance as philanthropic foundations continue to adopt private sector tools and tactics. In those early experimental years, Dr. Vivian Henderson, an economist, university president, and Ford’s first African American trustee, was concerned that the financial concern was taking over Ford’s social justice goals:

“The Program Related Investments I’m afraid are becoming very conservative; we’re now becoming bankers. […] We’re not taking any risks any more. We’re now examining every damn proposal just like the First National Bank of Chicago would examine it. […] I might raise a question about that behind closed doors and see if I might shake a little bit of it up.”Interview with Dr. Vivian W. Henderson for the Ford Foundation Oral History Project (April 16, 1973), 36. Ford Foundation records, Oral History Project, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Watch: Turning Around: A Look at Neighborhood Housing Services, 1974

Research This in the Archives

- “Opportunity Funding Corporation,” 1976-1982, Taconic Foundation, Grants, Series 1, Cooperative Assistance Fund, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “The difficult art of mixing philanthropy and business: An assessment of a grant to the Cooperative Assistance Fund (CAF) (Reports 002111),” 1972, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 1-3254, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Changing their ways to stay what they are: an assessment of the performance of the Southern Cooperative Development Fund, an organization assisting small farmers (Reports 004855),” 1976, Ford Foundation Records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 3255-6261, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Cooperative Assistance Fund — Ford Foundation PRI, Board of Trustees Meeting Notes and Reports (1 of 3),” Ford Foundation records, Programs, United States International Affairs Program (USIAP), Office Files of Louis Winnick, Subject Files, Series III, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Business for Social Responsibility (09600690) (rockarch.org),” Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants A-B, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In the fall of 2020, the Rockefeller Archive Center launched a new oral history and research project called Investing in the Good: Program-Related Investments and the Birth of Impact Investing. Directed by Dr. Rachel Wimpee, the assistant director of Research & Education at the Archive Center, the oral history project will include interviews with pioneers in the field. The book, coauthored by Wimpee, Eric John Abrahamson, and Alec Appelbaum will be developed as a resource for professionals and students in the fields of philanthropy, nonprofit management, and public policy.