Can philanthropy solve economic inequality? Should foundations use only the earnings from their investments to do their work, or should they sometimes spend capital? Are mission-related investments worth the financial risk?

Debates about the use of philanthropic assets are as old as foundations themselves.

This piece examines a century-old concept called “investment philanthropy,” which emerged at the birth of the Russell Sage Foundation in 1907. The idea is a close corollary to today’s mission-related investments, which are market-rate investments designed to support the mission of a foundation. The housing development project described below produced mixed results, but it may provide some lessons for today.

Birth of a Foundation for “Social Betterment”

The Russell Sage Foundation is the late-life creation of Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage (who preferred to be called Mrs. Sage), a multi-millionaire widow who aimed to use her late husband’s fortune for “social betterment.”The definitive biography of Mrs. Sage is Ruth Crocker, Mrs. Russell Sage. Women’s Activism and Philanthropy in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era America. Indiana University Press (2006).Mrs. Sage launched the Foundation, in her husband’s name, with the broad mission of “the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States of America.”Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage, “Letter of Gift,” (1907) Russell Sage Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.Now known for its contributions to social work professionalization and social science research, the Foundation in its early decades had a broad program, which set out to use “any means” to alleviate poverty and social problems.David C. Hammack, “The Russell Sage Foundation, 1907-1947: An Historical Introduction” in The Russell Sage Foundation: Social Research and Social Action in America, 1907-1947. Guide to the Microfiche Collection (1988), Rockefeller Archive Center.

The “Investment Philanthropy” Concept

To multiply the impact of the Foundation’s $10 million endowment, Mrs. Sage’s lawyer and chief philanthropic adviser Robert W. de Forest thought the new entity should engage in what he called “investment philanthropy.” In a December 1906 memo to Mrs. Sage, he outlined this investment approach:

“Income only should be used, for the Foundation is to be permanent and its action continuous. It might, however, say to the extent of one-half its capital, make investments for social betterment, such as tenement houses or lodging houses for women, with a limitation that such investments should always be on not less than a three percent basis.”“Suggestions for a Possible Sage Foundation,” Memorandum made by Robert W. de Forest for Mrs. Sage.” December 10, 1906. Russell Sage Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

[The Foundation] might, however, say to the extent of one-half its capital, make investments for social betterment…

In these hypotheticals, de Forest envisioned a cluster of for-profit housing projects for the working class, which would advance the Foundation’s purpose more effectively than would charitable contributions alone.

Donor Trepidation

But Mrs. Sage was uneasy with the idea of risking the endowment (and hence the Foundation’s longevity) in this way, writing:

“I have had some hesitation as to whether the Foundation should be able to make investments for social betterment which should themselves produce income, as for instance small houses or tenements… I realize that investments for social betterment, even if producing some income, may not produce a percentage as large as that produced by bonds… and that the income of the Foundation might be therefore diminished by such investments.”John F. McClymer, War and Welfare: Social Engineering in America, 1890-1925. Greenwood Press (1980) 57-58, op. cit. Crocker (2006) 226.

…the income of the Foundation might be therefore diminished…

Long-Term Stability vs. Short-Term Social Progress

In the end, Mrs. Sage struck a compromise in her letter of gift setting up the Foundation, allowing up to one quarter of the principal –rather than one half –to be made available for investment philanthropy. She further stipulated that such investments should yield a return of at least three percent.John M. Glenn, Lilian Brandt, and F. Emerson Andrews. Russell Sage Foundation. 1907-1946. Volume 1. Russell Sage Foundation (1947) 19.

The Concept in Action in Forest Hills

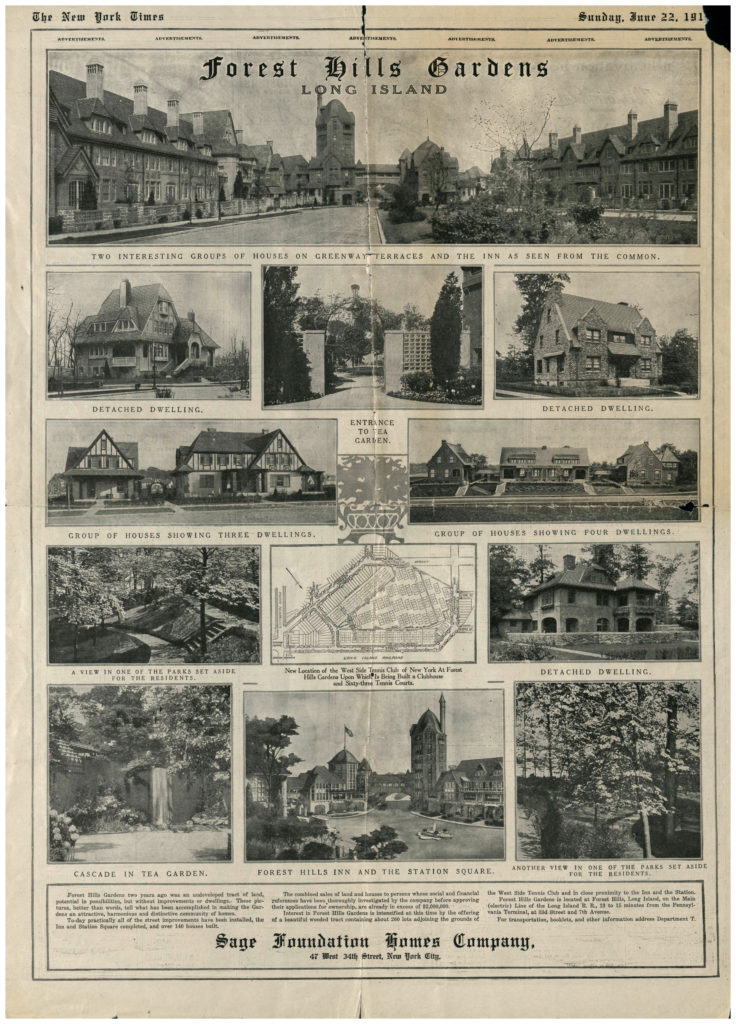

The largest investment endeavor was the Forest Hills Gardens affordable housing development in Queens, New York. Its developers aimed to create an ideal suburb for the working class inspired by the English “garden city” concept.

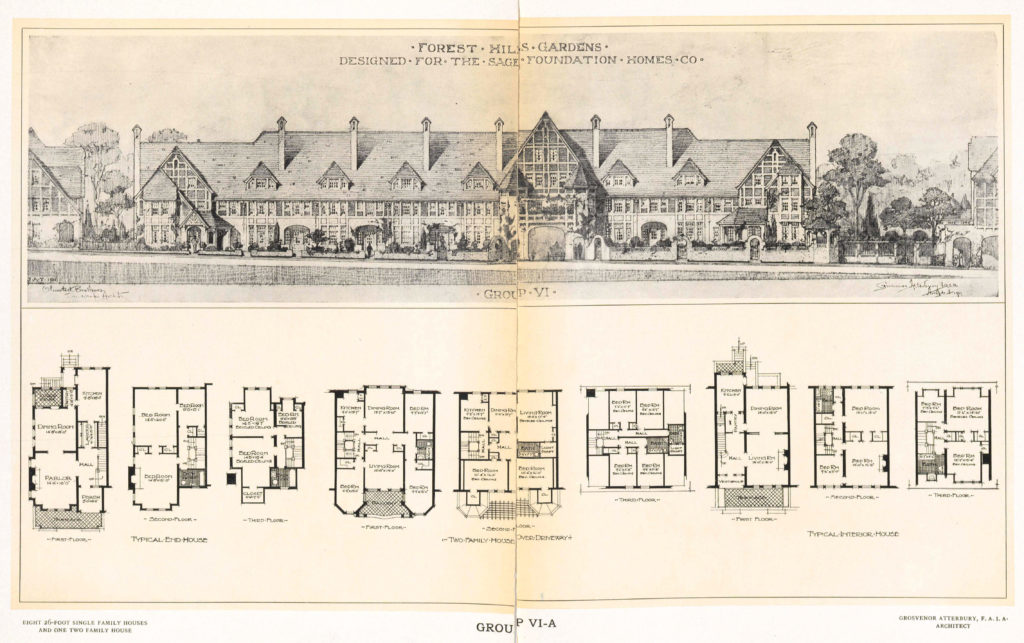

In 1909, the Foundation formed the Sage Foundation Homes Company, with none other than de Forest at the helm. The company purchased nearly 150 acres of land in Queens and hired architect Grosvenor Atterbury (who had designed de Forest’s home on Long Island) and landscape architects John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. to draft the plans.For more on the planning and development of Forest Hills, see “Early Office Files,” Russell Sage Foundation records Series 3, Rockefeller Archive Center.

It is not a charity.

Robert de Forest

In his pitch to potential buyers, de Forest was careful to promote the project as a “business investment of the Russell Sage Foundation […] conducted on strictly business principles for a fair profit.” To drive the point home, he emphasized, “it is not a charity.”Robert de Forest, “Forest Hills Gardens. What it is, Why it is, and What it is not.” Russell Sage Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The pitch worked. Forest Hills attracted buyers and investors and the development progressed. The Tudor-style buildings, gardens, and railway station made up an aesthetically pleasing architectural gem that still stands to this day.

A Sound Social Investment?

But how did the Forest Hills development measure up as an “investment philanthropy?” Unfortunately, not well at all. Although the development was praised as a model of town planning, the working-class population that was the intended beneficiary of the development was almost immediately priced out. Forest Hills’ “social betterment” objective failed. Neither was it a profitable investment. Instead of earning the expected three to five percent on its investment, the Russell Sage Foundation lost $300,000 by the time it pulled out of Forest Hills in 1922.

Leaving the non-profit field changed the rules and expected outcomes of the philanthropic project.

Moving beyond Forest Hills, Russell Sage Foundation trustees decided to pivot toward funding social policy research. Rather than invest in community projects such as Forest Hills, they instead launched a ten-year, twenty-two-county study of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut in hopes that the Foundation would have more impact on social equality through this mechanism than they had with bricks and mortar. No other American foundation would invest directly in real estate development again until the 1960s, when the idea for the device called a Community Development Corporation began to take shape.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “Forest Hills Gardens, Sage Foundation Homes Company maps,” 1911-1918, Russell Sage Foundation records, Subgroup 1, Early Office Files, Series 3, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Sage Foundation Homes Co.,” 1908-1914, Russell Sage Foundation records, Subgroup 1, Early Office Files, Series 3, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Income, Principal,” 1913-1927, Russell Sage Foundation records, Subgroup 2, Administrative, Series 1, Financial, Subseries 7, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Related

Supporting Economic Justice? The Ford Foundation’s 1968 Experiment in Program Related Investments

How the largest US foundation began supporting market-based projects in the late 1960s.

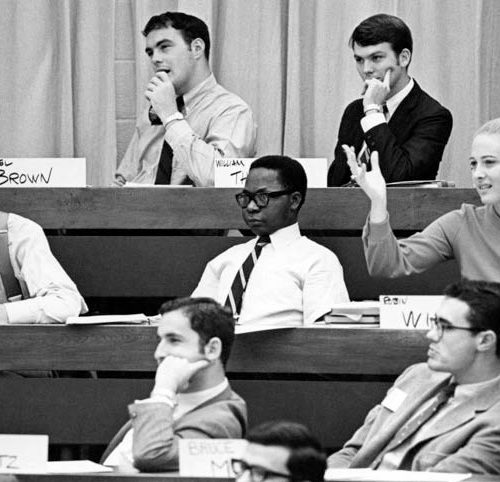

The Birth of the Modern MBA

Why would an American foundation transform the field of business education?

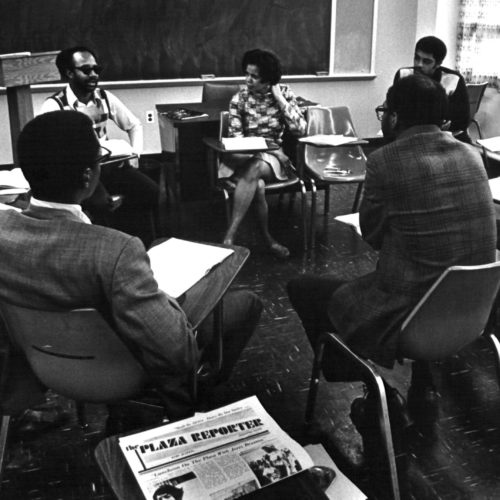

Photo Essay: Supporting Minority Enterprise in the late 1960s

In 1968, the Ford Foundation began to make social investments using a new tool borrowed from the for-profit world, the Program-Related Investment.

Timeline: Philanthropy and World War I

The onset of World War I created new demands on American foundations and donors.