When the restrictive military regime that had taken power in Brazil in 1964 became even more repressive by 1969, staffers at the Ford Foundation found themselves facing a conundrum. How would they continue to work in the region when government partnerships dissolved and their grantees were ousted from their jobs? One answer lay in creating a new, independent social sciences think tank.

The story of how Ford pivoted from working with public institutions to independent NGOs in Brazil is illustrative of a major shift in American philanthropic grantmaking in the twentieth century. In the 1960s, American foundations began to move away from forming close partnership with governments and instead began funding an independent civil society space.

Shifting Strategies in the Cold War

In the decade following World War II, the Ford Foundation became the largest foundation in the history of the US and the first billion-dollar philanthropic fund. At that time, its main overseas focus was the support of democracy and development in emerging nations. Working first in South and Southeast Asia and the Middle East, Ford’s strategy was to partner with foreign governments and public institutions to fund education, training, and local capacity. Ford Vice President Frank Sutton would later describe the tenet of development ideology of that time as follows:

Development needs to be pursued with the use of modern, empirical knowledge; it is achievable through rationally organized effort. Command over the requisite knowledge for development is open to all peoples through education and training. […] Governments, faithfully representing their peoples’ interests and aspirations, have central and primary roles in development.

Frank SuttonFrancis X. Sutton, Tom G. Kessinger, James P. Grant and George Zeidenstein, “Development Ideology: Its Emergence and Decline.” Daedalus Vol. 118, No. 1, A World to Make: Development in Perspective (Winter, 1989), pp.37-38.

From the start of Ford’s Overseas Development program in 1951, then, Foundation representatives would coordinate with the highest levels of government in each country of philanthropic activity. This was an obvious approach to work in urban planning, civic infrastructure, education, and agriculture — all fields in which the Ford Foundation engaged overseas.Francis X. Sutton, “International Philanthropy in a Large Foundation,” Jack Salzman, ed., Philanthropy and American Society. Center for American Culture Studies, Columbia University, 1987.

While often effective from the Foundation’s point of view, this development strategy relied on aligning strategies and goals with foreign government leadership. When leadership changed, foundation programs could come to a screeching halt.

The Ford Foundation in Brazil

As the Ford Foundation expanded its global presence from Asia and the Middle East to Latin America, this partnership strategy remained. Following the 1959 Cuban Revolution, Ford and several American entities, such as the International Cooperation Administration and USAID, engaged in Latin America to further pro-democracy goals.Carlos Eduardo Suprinjak, “The Ford Foundation and Brazilian Economics: Modernization, Community-Building, and Pluralism.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019, 2.Foundation funds supported, for the most part, technical assistance and what Ford dubbed “modernization” through universities and government entities. To cement its commitment to the region, Ford first opened a Brazil office in 1962, in Rio de Janeiro.Nigel Brooke and Mary Witoshynsky, Os 40 Anos da Fundação Ford no Brasil. The Ford Foundation’s 40 Years in Brazil. Ford Foundation, 2002.

In the decade that followed, Ford made the largest investments in Brazil that it would make for the rest of the century. Millions of dollars in grant funds in the 1960s supported basic science, agriculture, fisheries, agricultural economics, vocational education, teaching methods, business education and management training, reproductive biology, publishing, industrial engineering, libraries, economic studies, and more.Nigel Brooke and Mary Witoshynsky, Os 40 Anos da Fundação Ford no Brasil. The Ford Foundation’s 40 Years in Brazil. Ford Foundation, 2002.

The Ford Foundation and Social Sciences in Latin America

While important, investments in the sciences and agriculture were not as central to the Ford Foundation’s strategy as were those allocated to the social sciences. Where the Rockefeller Foundation was for decades the primary international science funder, from the late 1940s the Ford Foundation defined itself as a philanthropy to address other, human problems. The social sciences would be a key part of Ford’s efforts to establish peace, strengthen democracy and the economy, to support education and to better understand “individual behavior and human relations.”Report of the Study for the Ford Foundation on Policy and Program, November 1949. See Papers of the Study for the Ford Foundation on Policy and Program (Gaither Commission), Ford Foundation records, Programs, Policy and Planning, Rockefeller Archive Center.

To guide Ford’s social sciences programs in the region, Latin American Studies pioneer Kalman Silvert served as a program advisor to the Foundation from 1966 until his death in 1976.

Changing Political Regimes

In the midst of Ford’s large investments in Latin America, a wave of political change swept the region. In 1964, a military coup in Brazil had installed a more restrictive and right-leaning regime to replace the leftist government of João Goulart. But despite its crackdown on civil liberties and on political pluralism — and despite the resulting ethical dilemma of working in such a restrictive environment — the Ford Foundation’s activities remained relatively unchanged.Carlos Eduardo Suprinyak describes Ford’s view of the military coup “as a lesser evil when compared to the alternative offered by the continued government of João Goulart, who was believed to maintain far too close relations with communist groups both within and outside of Brazil.” Carlos Eduardo Suprinyak, “The Ford Foundation and Brazilian Economics: Modernization, Community-Building, and Pluralism.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019. Over the following years, however, the political climate became increasingly restrictive and violent. A handful of Ford Foundation-supported Brazilian scholars, including sociologist Fernando Henrique Cardoso, fled into exile.

Meanwhile, when a military junta took power in Argentina in 1966, the Ford Foundation created a fellowship program to relocate scholars that had been ousted from the University of Buenos Aires.

“A Coup Within a Coup” and the 1969 Military Junta in Brazil

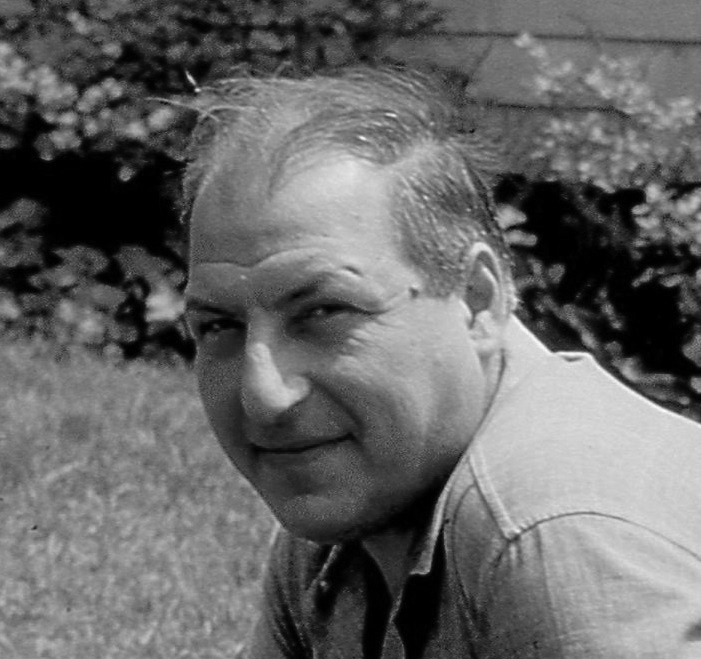

This march to extreme authoritarianism culminated in a “coup within a coup” on December 13, 1968 and then military junta in the early spring of 1969. William (Bill) Carmichael, the Ford Foundation’s representative in Brazil at the time, would later describe this moment:

I walked into the Brazil office in June 1968, only a few months [after arriving at the Ford Foundation], to watch the administration of Brazil take a sharp turn to the right and to have almost a coup within a coup in – on April 1st, 1969, when all Ford Foundation grantees and people in universities were kicked out of their jobs.

Bill Carmichael, Ford Foundation Representative to Brazil

To be sure, the previous government of Brazil, led by Costa e Silva, had pro-military and center-right inclinations. But this new regime led by a military junta went even further to eradicate the structures that had sustained democracy in Brazil. Freedom of the press and intellectual inquiry, as well as powerful public and private institutions were damaged and, in some cases, eradicated. Under Institutional Act Number 5, instituted on December 13, 1968, teachers and journalists were stripped of freedom of inquiry and freedom of speech.

The situation was a dramatic shift from the center-right government the military junta replaced. In effect, the new, authoritarian regime sough nearly absolute control over Brazil’s social and political discourse. Professors and intellectuals were fired, some of them were “disappeared” because their work ran counter to the regime’s goals and was deemed to be too political.

A Home for Brazilian Social Scientists

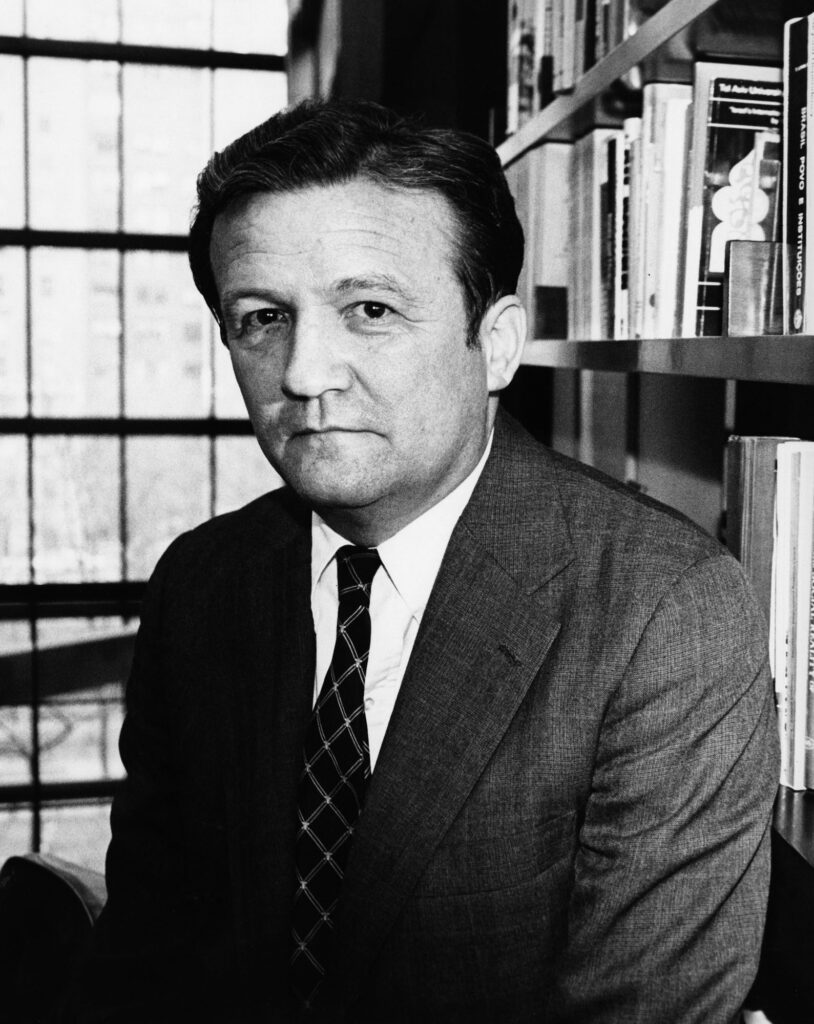

Meanwhile, Brazilian sociologist Fernando Henrique Cardoso had spent four years in exile in Chile. He approached his contacts at the Ford Foundation, including William “Bill” Carmichael, Ford’s representative in Brazil, in hopes of creating a new, independent think tank for social scientists unable to hold positions in the government-controlled public universities. The institution would be known as CEBRAP, the Portuguese acronym for the Center for Brazilian Analysis and Planning.

When Carmichael and program officer Peter Bell first wrote a grant recommendation for this new Brazilian think tank, however, the New York office of the Ford Foundation turned it down. That’s because Ford’s strategy was to tackle root causes of problems, not consequences. Foundation leadership, while sympathetic to the plight of individual scholars, believed they should not be involved in scholar rescue and should focus instead on structural change.

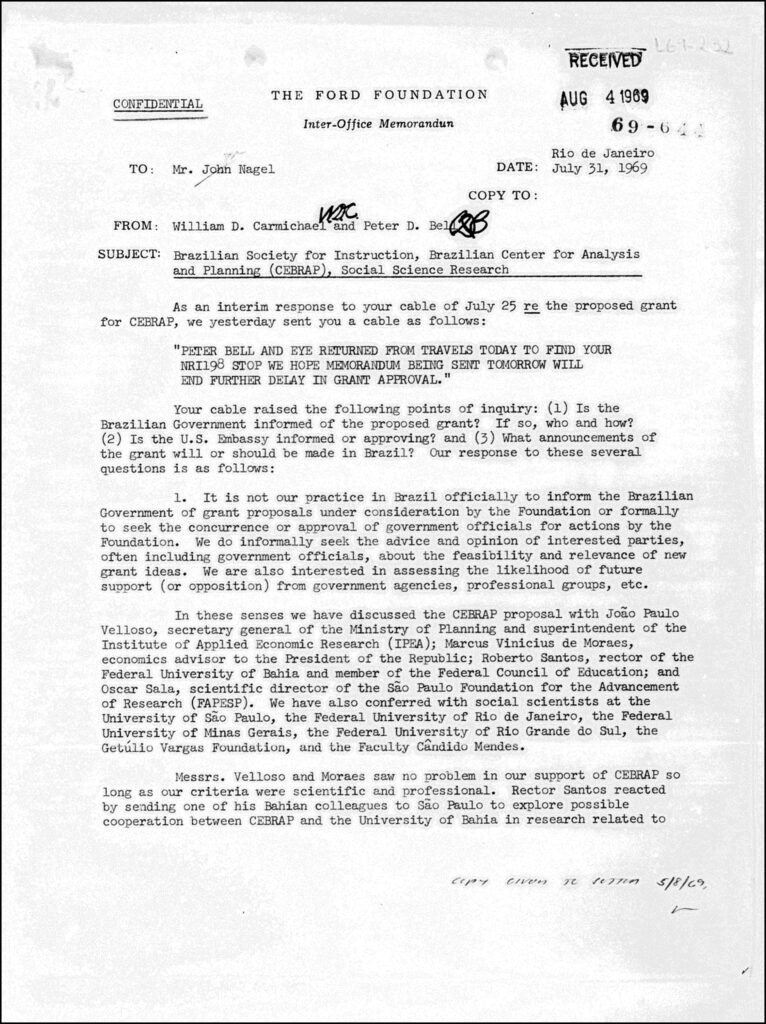

Carmichael and Bell got back to work on a second grant recommendation, instead framing the project as institution-building to save Brazilian social sciences — no longer focusing on the ousted social scientists themselves as the beneficiaries. The new version, a July 31, 1969 memo, explained:

The Request for Grant Action […] may have placed undue emphasis on the ‘rescue’ aspect of CEBRAP. We see the proposed grant as an unusual opportunity for the Foundation to assist in the development of the social sciences in Brazil, and we see nothing programmatically ‘abnormal’ about the proposal. To the contrary, the grant would be fully consonant with our established program in the social sciences in Brazil.

William D. Carmichael and Peter D. Bell to John Nagel, Rio de Janeiro, July 31, 1969Confidential Inter-Office Memorandum, July 31, 1969, Brazilian Society for Instruction (06900644)” $893,000. September 3, 1969-September 30, 1976, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants, Grants A-B, Rockefeller Archive Center.

It was in this vein that Cardoso would later describe the aims of CEBRAP as nothing less than democracy itself:

[W]e decided to start a new private think-tank called the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning, or CEBRAP. The foundation would produce sociological and economic studies, but the political goal was always to support democracy.

Fernando Henrique CardosoFernando Henrique Cardoso, The Accidental President of Brazil. (Public Affairs, 2006) p.188.

While not documented in the archives, Carmichael is said to have placed a phone call to New York after writing the July 31 memo, threatening to leave his post if Ford could not come through with the grant support for CEBRAP.William Carmichael interview with the author, February 2014.

This time, New York approved the grant.

“Breaking the rules”: Neither Sanctioned by nor Working against the Brazilian Government

With Ford support secured, the question remained: how would the Brazilian government respond?

In Bill Carmichael and Peter Bell’s July 31, 1969 memo to John Nagel, the deputy of Ford’s Latin America and the Caribbean program, the two staffers addressed head-on the issue of supporting a non-governmental entity. While insisting that “it is not our practice in Brazil officially to inform the Brazilian Government of grant proposals under consideration,” they do list several members of government they had informed of the plans. They hoped to calm any fears that may emanate from New York headquarters.

Cardoso would later describe the thinking at the time:

There is a peculiarly Brazilian way of breaking the rules in which, as long as you insist you are obeying the law, you can get away with pretty much anything.

Fernando Henrique CardosoFernando Henrique Cardoso, The Accidental President of Brazil. (Public Affairs, 2006) p.187.

The Center for Brazilian Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP) is Established

The grant establishing the new think tank, CEBRAP, was made to the Brazilian Society for Instruction. The purpose was “support for social sciences research at the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning.”“Brazilian Society for Instruction (06900644)” $893,000. September 3, 1969-September 30, 1976, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants, Grants A-B, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Despite decades of continued political repression and authoritarianism, CEBRAP would continue to produce research on the Brazilian economy and society, publishing ideas that carved out a space for later human rights and social justice work. In 1975, the Ford Foundation provided CEBRAP with endowment support and for years would fund research projects through the institution.For endowment support, see “Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP)” Grant 07500593, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants, Grants A-B, Rockefeller Archive Center. There are at least eighteen other Ford Foundation grants to CEBRAP up to 1996 in the Ford Foundation records preserved at the Rockefeller Archive Center.

Over the decades, CEBRAP would foster a “second generation” of Brazilian scholars and leaders who would later fill the ranks of governmental leadership.Peter S. Cleaves and Richard W. Dye, “Bringing Vision, Mission, and Values to Philanthropy” in Abraham F. Lowenthal and Martin Weinstein, eds., Kalman Silvert. Engaging Latin America, Building Democracy. Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2016, p.126.

The End of Collaboration with Governments in Latin America

The political upheaval across Latin America, which began in the 1960s, forced the Ford Foundation to change overseas grantmaking strategies quickly. By 1971, Ford Latin America Program Advisor Kalman Silvert was helping to develop a foundation policy — or at least a philosophical approach — to working with what he called “distasteful regimes.” He wrote:

I should like to advance the argument that if we cannot make a very strong case for distinguishing our activities from the support of politically repressive behavior in the host country, then we should withdraw. If, however, we see our programs in a given host country as contributing to the preservation of some pluralism that may come to flourish even in an undefined future, or as contributing to the immediate welfare of such populations as undernourished children, then we should remain even if some marginal benefit flows to the repressive host government.

Kalman Silvert, 1971.“Distasteful Regimes and Foundation Policies Overseas” Memo from Kalman H. Silvert to David E. Bell, October 18, 1971, in “1973 October 1-9,” Ford Foundation records, Latin America and the Caribbean Program Files on the 1973 Coup d’Etat in Chile.

Ford would face even more violence in Chile in 1973. Although Ford retained many of its Latin American offices and programs, by the end of the 1970s it was no longer feasible to work hand-in-hand with foreign governments. Reflecting on this shift years later, Bill Carmichael explained that, after 1969, Ford Foundation’s Latin America program “abandoned any assumption that ‘our natural client is the host government.'”Mary McClymont and Stephen Golub, eds., Many Roads to Justice. The Law-Related Work of Ford Foundation Grantees Around the World (Ford Foundation, 2000), 24.

Furthermore, by the decade’s end, the social sciences themselves were no longer a programmatic focus for the Ford Foundation. A 1979 report, “Brazil Office Profile,” acknowledged that Ford had “moved away from general capacity-building and discipline-building in the social sciences.”Brazil Office Profile, memorandum to Franklin A. Thomas of November 19, 1979, “Brazil Program Papers (Reports 013006),” 1979, Catalogued Reports, Ford Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

It was the conclusion of a particular era of American development ideology.

[The Ford Foundation] abandoned any assumption that our natural client is the host government.

Former Ford Foundation Vice President Bill CarmichaelMary McClymont and Stephen Golub, eds., Many Roads to Justice. The Law-Related Work of Ford Foundation Grantees Around the World (Ford Foundation, 2000), 24.

Further Reading

- Felipe Amorim, “Political Instability, Modernization, and the Institutionalization of Brazilian Political Science in the 1960s.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2021.

- Elizabeth Cancelli, “Brazil: Transition and Reconciliation, a Cold War Strategy.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Daniel W. Franken, “Hookworm Eradication in Brazil and Beyond.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Jonathan Coulis, “Rural Extension and Agricultural Transformation in Minas Gerais, Brazil, 1948-1960.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Livio Sansone, “From Afro-Brazilian into African Studies.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.

- Andrés Jiménez Ángel, “‘Law and Development’ in Latin America, 1965-1979.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.

- Carlos Eduardo Suprinyak, “The Ford Foundation and Brazilian Economics: Modernization, Community-Building, and Pluralism.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.

- Júlio Barnez Pignata Cattai, “The American Legal Programs in Brazil: From Modernization Theory to Human Rights.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2019.

- Rafael R. Ioris, “A Tale of Missed Opportunities: The Role of the United States in the Protracted Modernization of Brazilian Capitalism.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2017.

- Shawn Moura, “Modernization through Home Economics: The American International Association in Brazil, 1947-1961.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2017.

- Juan Jesús Morales Martin, “Interinstitutional Cooperation in Authoritarian Times: The Ford Foundation and the Development of Autonomous Research Centers in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile (1969-1990).” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2016.

- Arianna Kinsella, “Philanthropy during the Cold War, 1958-1985: A Case Study for Brazilian History in the United States and the Social Sciences in Brazil.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2013.

- Rodrigo Cesar Da Silva Magalhães, “International Cooperation in Health in the Interwar Period: The Rockefeller Foundation’s Worldwide Anti-Yellow Fever Campaign and its Implementation in Brazil (1918-1939).” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2012.

- Ana Paula Korndörfer, “Fighting Ancylostomiasis (hookworm infection) in Southern Brazil: Cooperation between the Rockefeller Foundation and the Government of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (1919-1923).” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2010.

- Mariano Plotkin, “Modernity, Development and the Transnationalization of the Social Sciences in Argentina and Brazil (1930-1970).” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2008.