In 1969, the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) partnered with Ted Watkins, a local civil rights activist, to begin supporting a new jobs program in Watts, a low-income neighborhood in South-Central Los Angeles.

At the time, Watts had become an emblem of urban poverty, segregation, and decline. Nearly thirty percent of its residents lived below the poverty line; its unemployment rate was about three times the national average; and about two-thirds of its high school students dropped out before graduation. Just four years earlier, the area had witnessed one of the deadliest and most expensive race riots in US history after a police officer stopped an African American driver on the suspicion of drunk driving.Robert Bauman, Race and the War on Poverty: From Watts to East L.A. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 31, 34; “A Proposal to Establish an Urban Residential Education Center,” Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

These factors presented most social sector organizations working in the neighborhood with a series of unique challenges.

This was especially true for the RF.

To date, the Foundation had almost no experience supporting social action programs in places like Watts. Instead, the Foundation had traditionally taken a far more elitist approach in its equal opportunity work, funding higher education initiatives for a small number of high-achieving minority students.

This strategy left the RF almost completely disconnected from black communities and grassroots activists in the inner cities, and left unchallenged the structural forces — racial discrimination in the labor and housing market, as well as segregated schooling — that continued to reinforce systemic racism across the country.

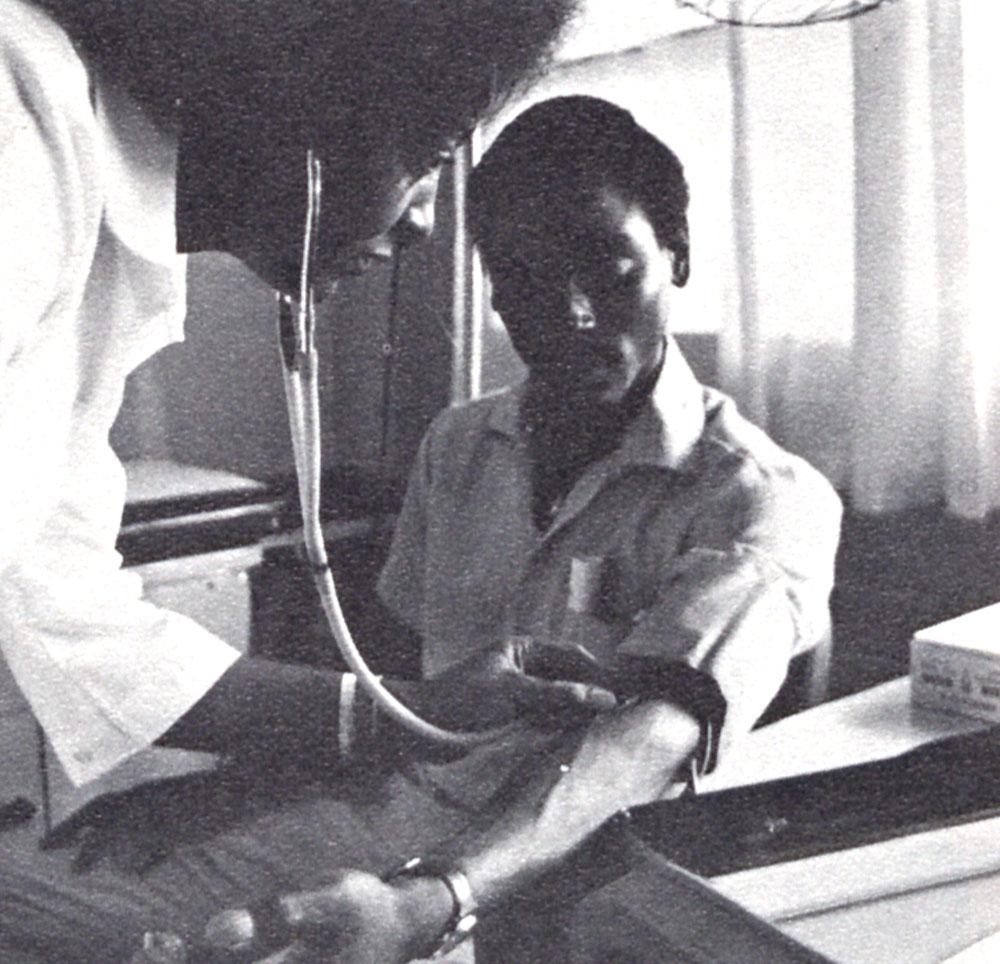

But this began to change in 1969, when the RF worked with Ted Watkins to support the Watts Labor Community Action Committee’s (WLCAC) paramedical training program, which trained at-risk youth to become dental assistants, physical therapy aides, EKG technicians, and licensed vocational nurses in and around Watts.

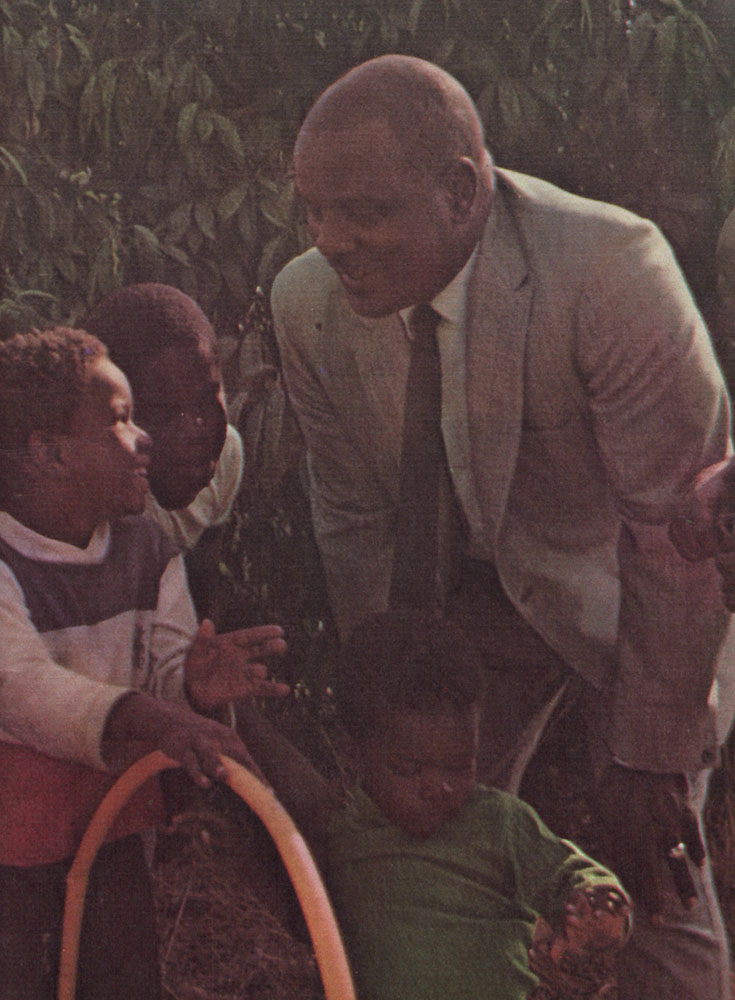

On the surface, a partnership between Ted Watkins and the RF appeared most unlikely. Watkins was an African American social activist born in the Jim Crow South. He had migrated to Los Angeles as a young teenager in 1935 to avoid a Mississippi lynch mob and, once there, began working for the Ford Motor Company. Eventually, he became a leading member of the United Auto Workers and joined the NAACP’s local Watts chapter. Dismayed by political infighting over administering Los Angeles’ federal antipoverty funds, he and other union workers shortly thereafter formed the WLCAC as an independent community development agency in the summer of 1965.Bauman, 17-30; “Conversations with the Inspiring Tina Warkins-Quaye,” VoyageLA.

RF leadership, on the other hand, was comprised mostly of well-to-do whites (except for its sole African American trustee, Ralph Bunche) who lacked first-hand knowledge of inner-city life.

Despite these differences, however, Watkins and the RF developed an extremely effective partnership. The Foundation relied upon Watkins to be its eyes and ears in the neighborhood, and he in turn made the WLCAC a safe, and potentially high impact, investment for RF dollars. On the whole, Watkins was the main reason the Foundation supported a new jobs program in Watts.

Kenneth W. Thompson, Director of the RF Social Sciences Division, on Ted Watkins, 1968

He is getting things done which practically no one else in the ghetto is doing.

In the end, because an unexpected re-distribution of federal welfare money caused Watkins’ organization to curtail its activities, this new jobs program did not achieve all of its desired results. Nevertheless, the Watkins-RF partnership was significant. It highlighted an elite foundation’s ability to identify, and lean on, strong civil rights leaders on the ground; it marked one of the first direct RF efforts to promote economic opportunity in America’s inner cities; and, more broadly, it reflected organized philanthropy’s growing support for the social justice movements of the 1960s. What began as an unlikely partnership evolved into a strong collaboration that helped RF civil rights strategy leave the ivory tower and enter the inner-city.

A Chance Encounter

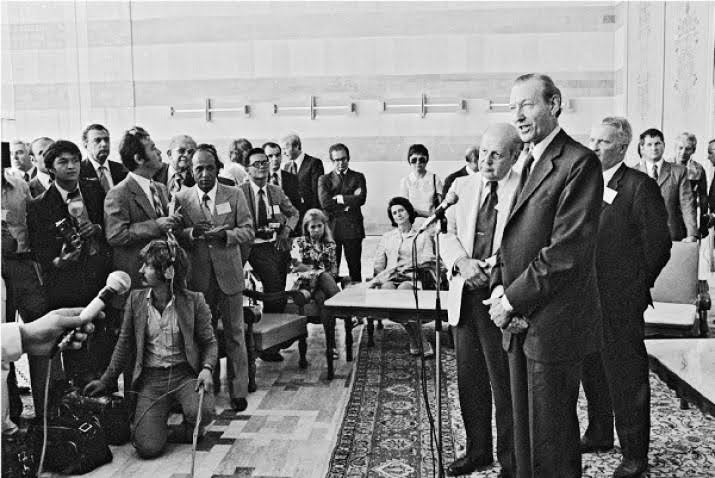

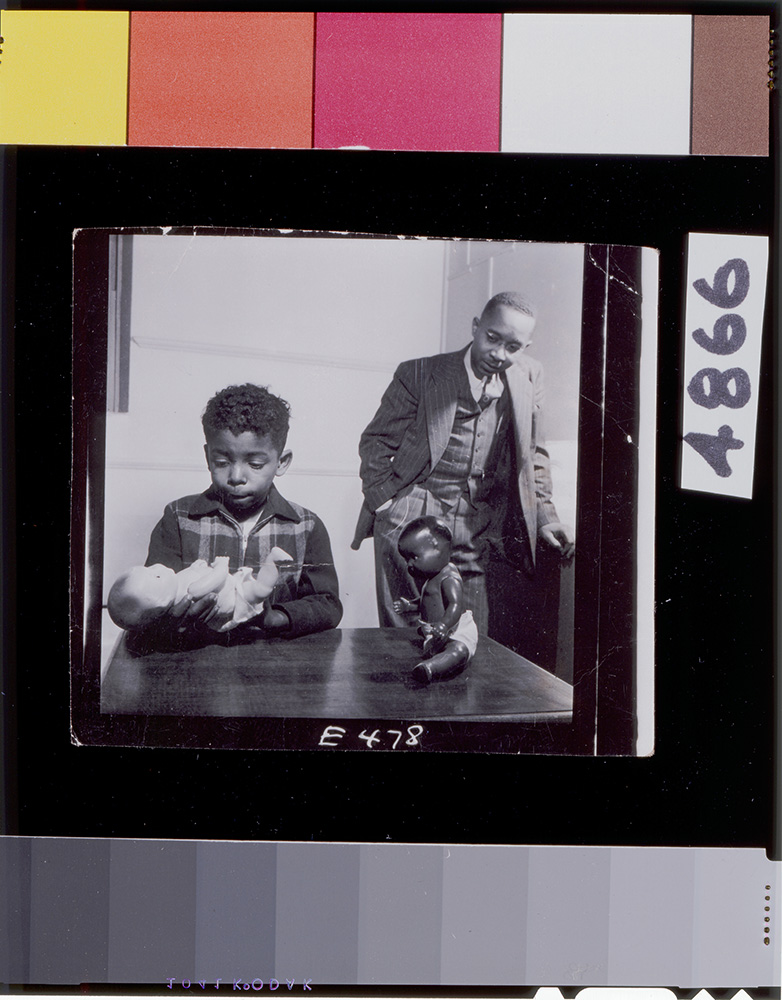

Foundation leaders first met Ted Watkins in March 1968, during a special meeting of an RF trustee-staff committee with some of the nation’s leading civil rights figures, including Kenneth Clark, a black psychologist whose work helped inform the Brown decision, Floyd McKissick, National Director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and Roy Wilkins, Director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The trustee-staff committee had formed in December 1967 to explore the ways in which the RF might begin improving the conditions of America’s poor and minority-populated urban neighborhoods.

A string of riots in the summer of 1967 — over 150 total and many triggered by the nature of the policing of heavily black neighborhoods — had recently brought national attention to the issues of these neighborhoods. Indeed, just a month before Watkins met with RF leaders, the Kerner Commission, created by President Lyndon Johnson to investigate the riots’ causes, concluded that the US was headed “toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”Justin Driver, “The Report on Race That Shook America,” The Atlantic, May 2018.

As a result of these developments, some within the RF wanted to give the Foundation’s equal opportunity work a major facelift. Rather than supporting the college aspirations of elite minority students, they argued, the RF needed to initiate more relevant and impactful work in the inner city. As one commentator noted:

For some, it appeared that the Foundation had been ‘whistling Dixie while the country was burning.’Elizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History,” 239-40, Richard Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Ted Watkins’ Economic Philosophy

At the March 1968 trustee-staff meeting, Ted Watkins found himself seated between two significant players: Tom Watson, the committee’s chair, and John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Chair of the RF Board. Despite their cultural differences — Watkins attended the meeting in a black turtleneck and bragged about buying his clothes out of the trunk of a car — the three men hit it off.ibid.

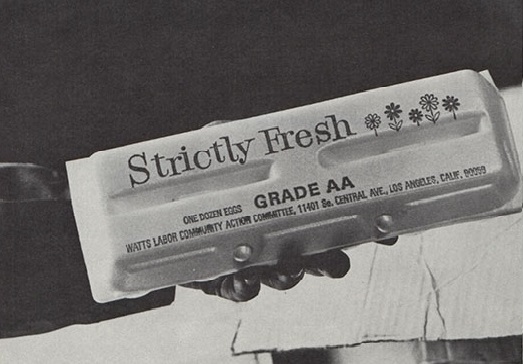

The key point of discussion was Watkins’ desire to revitalize Watts economically from the inside-out through the private sector. His main idea was to foster black economic security in the neighborhood by creating community-run businesses, new jobs, and vocational training programs that prepared residents for upwardly mobile careers in locally based industries.

While Watkins endorsed black self-reliance, he recognized the need to solicit capital from elite, predominantly white funding sources like the RF. At the end of the day, Watkins reasoned, these funds would spark the commercial development necessary to develop an economic base in the neighborhood.“Visit to Watts Labor Community Action Committee, Los Angeles, California, February 5-8, 1972,” 14-16, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.5, Series 200A, Rockefeller Archive Center.; Bauman, 72-73.

This desire to promote black financial security and entrepreneurship through normal economic channels made Watkins an attractive partner to both Watson and JDR 3rd. As one observer later recalled:

The character of Ted Watkins is so important. He was a man who was interested in free enterprise – and that was something that both the other men understood.Romney, 239-40.

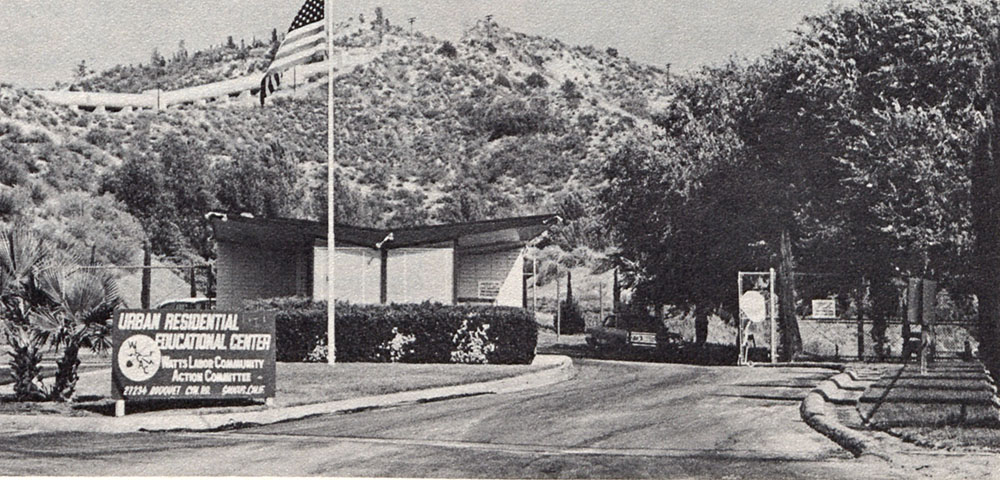

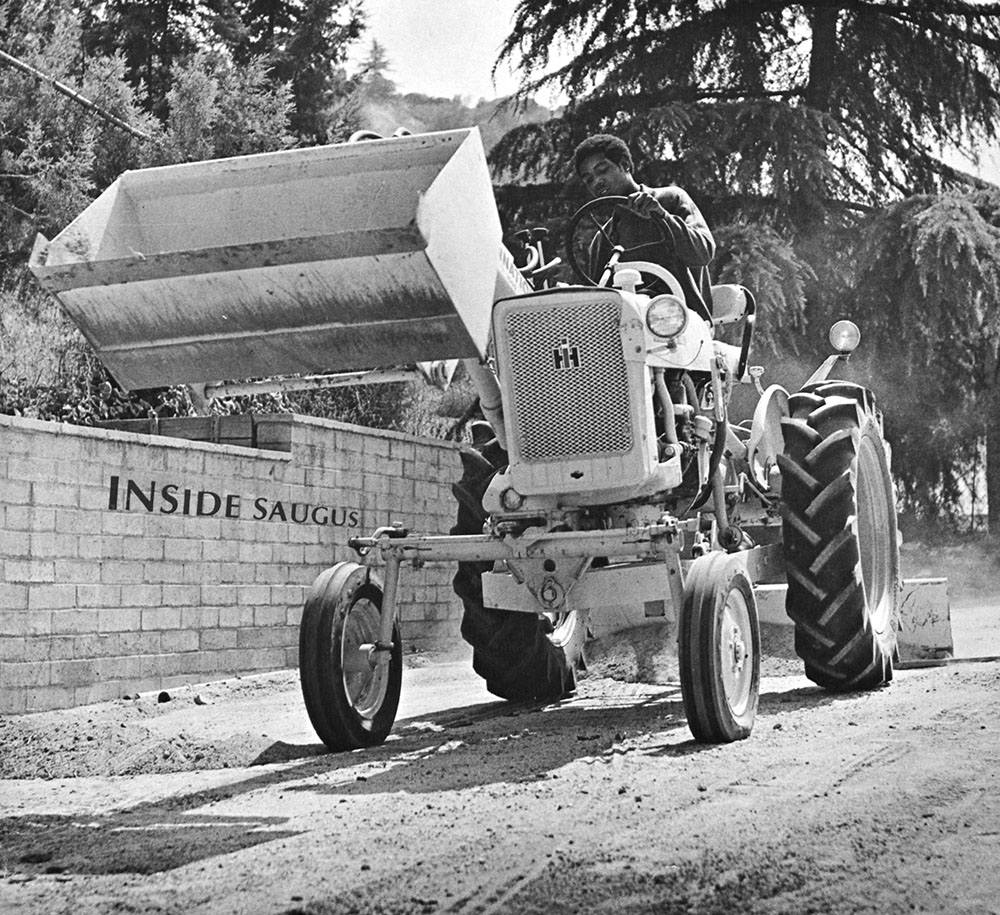

Guided by this philosophy, Watkins launched several key initiatives in Watts. By the early 1970s, he had opened a credit union; established various community-owned businesses, including two gas stations, a poultry farm, and a laundromat; and, with Ford Foundation money, begun to support local minority-owned small businesses. At this time, WLCAC also became a Community Development Corporation, a tax-exempt nonprofit that solicited private investment in low-income areas, and, with a $2.1 million grant from the Department of Labor, created a 600-acre job training facility for high school dropouts in Saugus, an area located roughly 40 miles north of Watts. Bauman, 74-75, 78; Kenneth W. Thompson Diary Entry, December 9, 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center; “A Proposal to Establish an Urban-Residential Educational Center,” November 18, 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

RF officials were awe-struck by these accomplishments. Watkins seemed to have single-handedly created an oasis of economic potential in the middle of one of America’s most destitute neighborhoods. As one RF officer noted after a site visit to Watts, “He is getting things done which practically no one else in the ghetto is doing.”

An outright grant-in-aid, to enable Watkins to do what desperately needs doing but do it better, would be money well-spent.Kenneth W. Thompson Diary Entry, April 23, 1968, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The RF Goes Interdisciplinary

One of the most important initiatives at Saugus – and the one that received the most RF funding – was the paramedical training program.“Watts Labor Community Action Committee – Paramedical Training Grant,” June 20, 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.5, Series 200A, Rockefeller Archive Center; Allocation No. 2 for WLCAC Grant, January 24, 1972, Rockefeller Foundation records, Series 200A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Choosing to invest in this program illustrated the ways in which the RF sat at a strategic crossroads in the late 1960s, still tethered to its traditional program areas while simultaneously exploring new ones demanded by the era’s social and political transformations.

By this time, the RF had become internationally renowned for its work in public health and medicine. Guided by the notion that illness was the root cause of other social problems, the Foundation had launched demonstration projects to control the spread of disease around the world, supported the professionalization of medical and public health education, and built global research networks that developed and spread new medical advances. These efforts placed public health at the core of the Foundation’s institutional DNA.

But in 1963, as part of a more general emphasis on confronting new challenges in the developing world, the RF created five new interdisciplinary program areas, including Toward Equal Opportunity For All (EO), which managed the Watts grant. While the Foundation maintained traditional academic divisions — Agricultural Sciences, Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, and Medical and Natural Sciences — they now worked in concert to attack problems holistically, from multiple perspectives.

It is possible that the RF would never have made the paramedical grant if not for this interdisciplinary structure. A medical scientist alone would have likely been ill-equipped to support a new job training program in Watts. But having both medical scientists and social scientists in the EO program made supporting the paramedical initiative possible. In this way, being interdisciplinary helped the Foundation fuse its traditional interest in public health with its newfound focus on economic inequality.

A New Program Is Born

What sold both Ted Watkins and the RF on paramedical training, though, was a heavy demand for hospital workers in the local economy and the potential for paramedics to climb the occupational ladder in Watts.

Indeed, the neighborhood’s soon-to-be created Martin Luther King, Jr. Hospital required 1,500 new paramedics, and, as an added bonus, was affiliated with the Charles R. Drew Postgraduate Medical School. The Medical School would provide paramedical workers with opportunities to enroll in continuing education classes and thus attain new positions within the medical field. Bauman, 76; Guy Scull Hayes Diary Entry, May 6-8, 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center; John P. O’Connor to Ted Watkins, May 29, 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.5, Series 200A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

With Watkins ‘in the driver’s seat,’ one gets the feeling that it will pay off.

Guy Scull Hayes, Assistant Director of the RF’s Natural and Medical Science Division, on the WLCAC paramedical training grant, 1969

As a result, Watkins believed the program could eventually create a generation of black doctors in Watts who would both bring economic stability to the neighborhood and raise the aspirations of its younger residents. Guy Scull Hayes Diary Entry, January 2-7, 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Confident in Watkins’ skill as a community organizer and the local need for new paramedics, the Foundation provided the WLCAC with a three-year, $460,000 grant for the new program in June 1969.WLCAC Paramedical Training Grant, June 20, 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.5, Series 200A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

A Successful Experiment

It was the RF’s faith in Ted Watkins, more than anything else, that made this grant possible. As Guy Scull Hayes, Associate Director of the RF’s Natural and Medical Sciences Division, noted, supporting a new and untested program in Watts was “a gamble with high stakes, but the return could be enormous…With Watkins ‘in the driver’s seat,’ one gets the feeling that it will pay off.”Guy Scull Hayes Diary Entry, May 6-8, 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

But the program’s chances for success were prematurely curtailed. In 1973, the paramedics program closed when President Nixon, committed to decentralizing the US welfare system, reshuffled the WLCAC’s Department of Labor funding. Without access to its $2.1 million federal grant, Watkins had to end several WLCAC initiatives. The RF tried to pick up the slack, but, facing economic troubles of its own, eventually told Watkins it could not offer him the much larger funding needed to continue the program.Guy Scull Hayes Diary Entry, January 3, 1974, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Nonetheless, there was an important silver lining: the RF had forged one of its first significant partnerships with a civil rights activist in the inner city, not only offering him financial support, but also allowing him to drive Foundation strategy in a brand new program area. While the paramedical training program ended prematurely, the impact of the Watkins-RF partnership endured. It demonstrated the collaborative potential between elite philanthropists and grassroots actors, and helped the RF develop a strategy more squarely centered on promoting economic opportunity in urban America.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “Watts Labor Community Action Committee (07100335),” 1971-1973, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Grants U-Z, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Watts Labor Community Action Committee, Ted Watkins — Memoranda, Correspondence, Evaluations of Shop Rite Markets (1 of 2),” 1971-1972, Ford Foundation records, Programs, National Affairs Division, Vice President, Office Files of Mitchell Sviridoff, Administrative Subject Files, Series I, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “WLCAC: the first decade: an assessment of the Watts Labor Community Action Committee (Reports 006225),” 1976, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 3255-6261, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Far from enough, but enough to be important: an assessment of Foundation grants to the Watts Labor Community Action Committee (WLCAC) in Los Angeles, California (Reports 006512),” Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 6262-9286, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Watts Labor Community Action Committee – Paramedical Training,” Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Research Group 1, Subgroup 1.3-Subgroup 1.8 (A76-A82), Projects (A78), Subgroup 5, United States, Series 200, Medical Sciences, Subseries A, Rockefeller Archive Center.