Public Television History and American Foundations

The American public broadcast system as it exists today came out of years of work by organized philanthropy. Across more than two decades following Word War II, the Markle Foundation, Carnegie Corporation, and the Ford Foundation helped carve out a non-profit forum in the fast-growing world of televised entertainment. They moved this new idea forward through leadership, research, experimentation — and millions of dollars in grants. When the Public Broadcasting Act was passed in 1967, it signaled both the culmination of all this prior work and the birth of a new era in television.

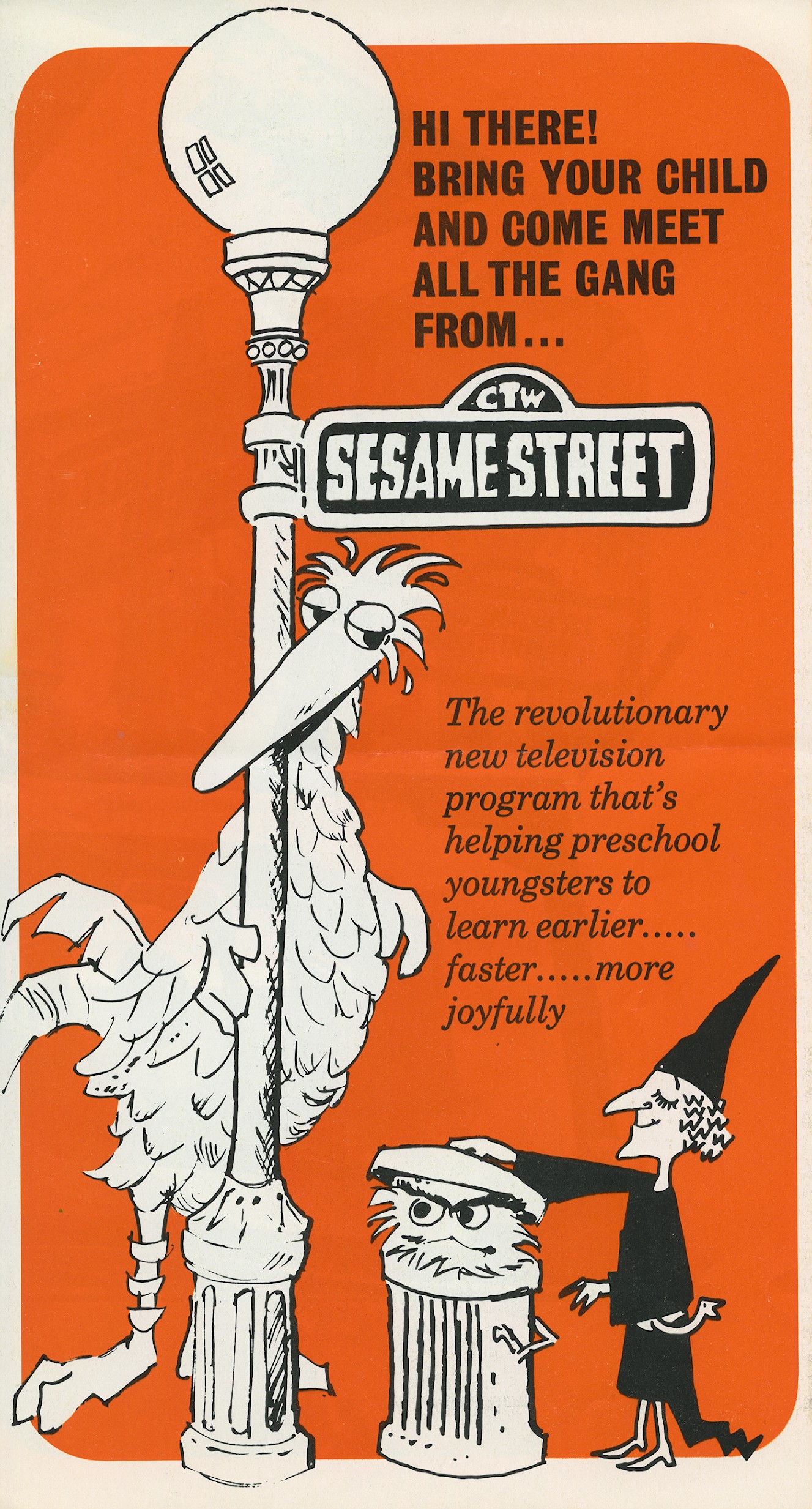

The well-known public television programs and TV stations that many Americans grew up with have an interesting prehistory. Before the emergence of a robust menu of children’s programs, documentaries, and recorded “great performances,” before Sesame Street and other programs borrowed the techniques of commercial advertising to achieve educational goals, public programming was firmly “instructional.”

Instructional Television

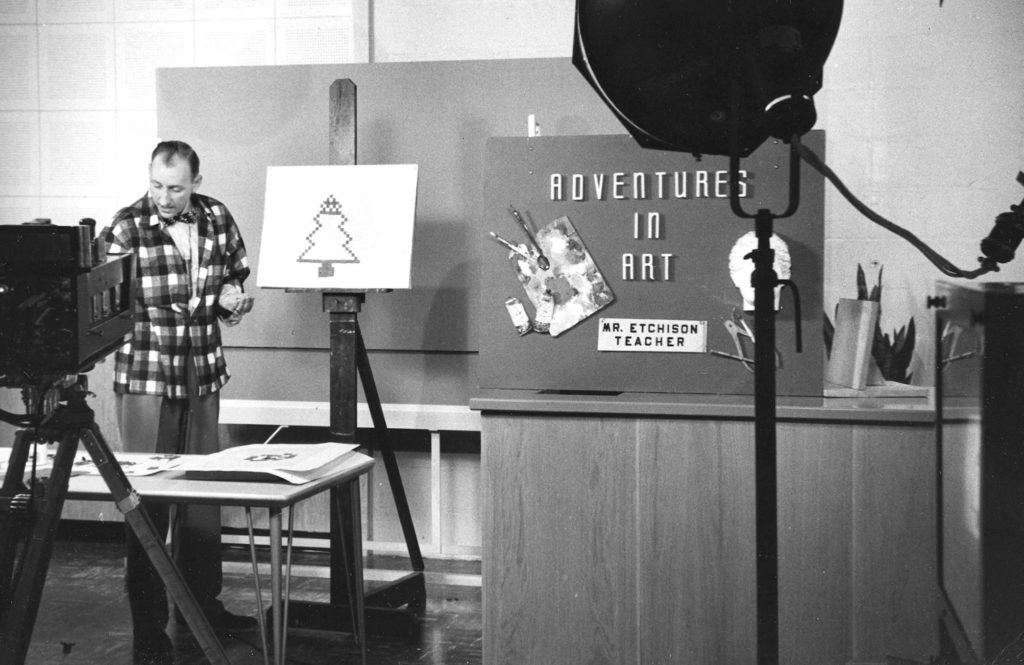

In the 1950s and early 1960s, whether geared to children or adults, instructional programs tended to present classroom lectures without much attention to the aesthetic or technological possibilities of this new medium. Furthermore, programs were constrained to local distribution areas, with little means of reaching a national audience.

Ford’s Fund for the Advancement of Education made over $5.6 million in grants to schools, colleges, and universities for endeavors that essentially were closed-circuit, often distance-learning programs. They took the form of straightforward presentations of professors giving lectures, or teachers conducting classroom instruction. Some funding enabled released time for faculty to develop “telecasts.”

Mid-Century American Television

In 1950, only twenty percent of American households owned a TV set. By 1960, that number had risen to ninety percent.Jordan, Winthrop. The Americans. Boston: McDougal Littell, 1996: 798. Between 1949 and 1969, the number of households with at least one TV set rose from less than a million to 44 million.“Television.” The World Book Encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book Inc., 2003: 119. The number of commercial TV stations rose from 69 to 566. The amount advertisers paid these TV stations and the networks rose from $58 million to $1.5 billion.

On the one hand, this kind of explosive growth seemed promising for educational television programming. Yet television broadcasting was so expensive that running shows that couldn’t earn a profit just didn’t make sense to network executives. Continental Classroom, for example, was a rare, large-scale crossover project in which telecast lectures from college courses were broadcast on commercial channels in the NBC network. Of course, that program was only made possible by a $1 million grant from the Ford Foundation.“American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education,” Grant #05900549, September 30, 1959-May 15, 1961. Ford Foundation records, Grants A-B, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Radio, in contrast, had been able to offer non-profit programs time slots in the middle of the night. Television wrapped up its broadcast day at midnight. Because television was dependent on coaxial cable laid down nationwide by AT&T, broadcasters had to consider everything in terms of cost.

That’s when foundations stepped in.

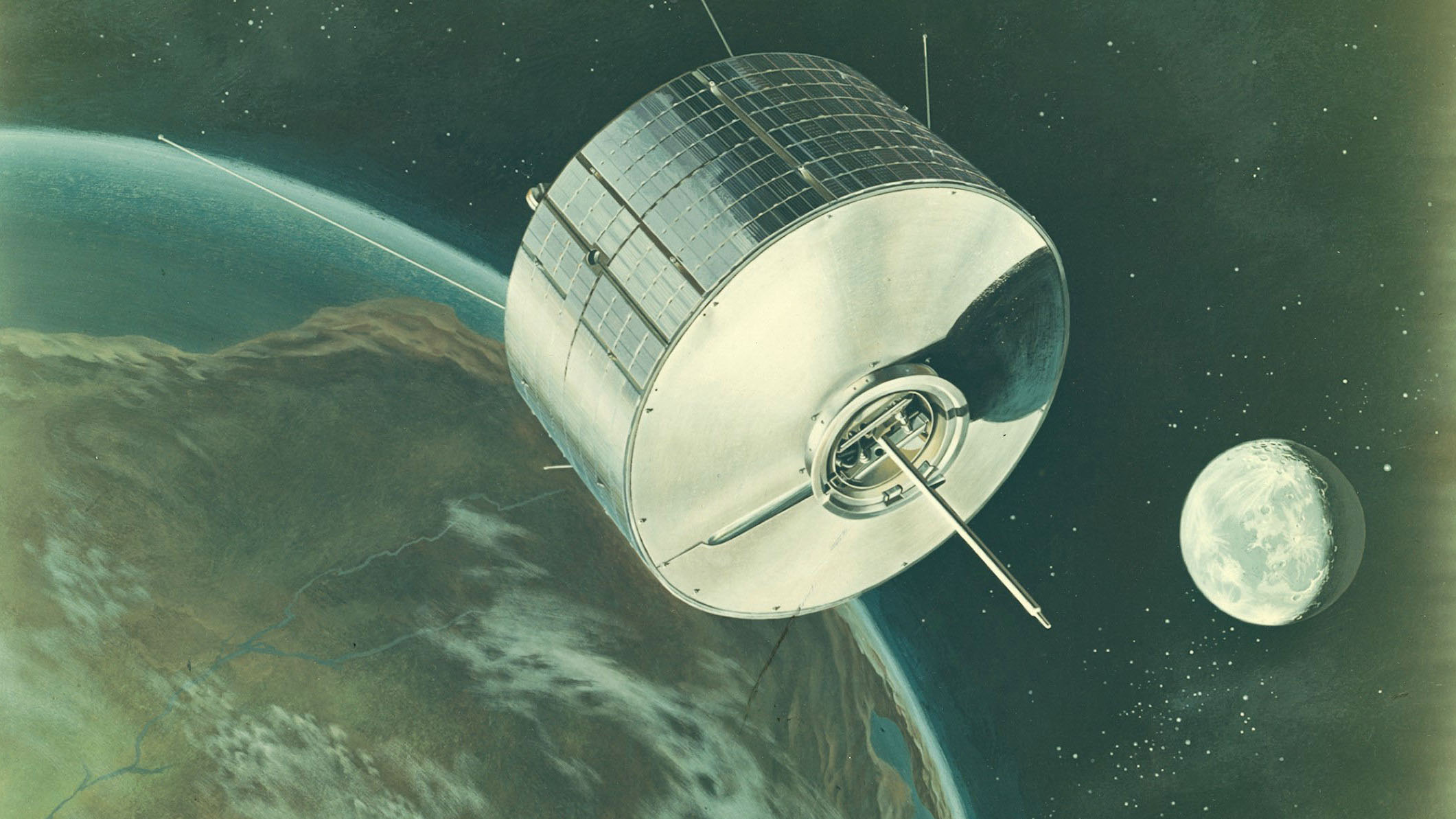

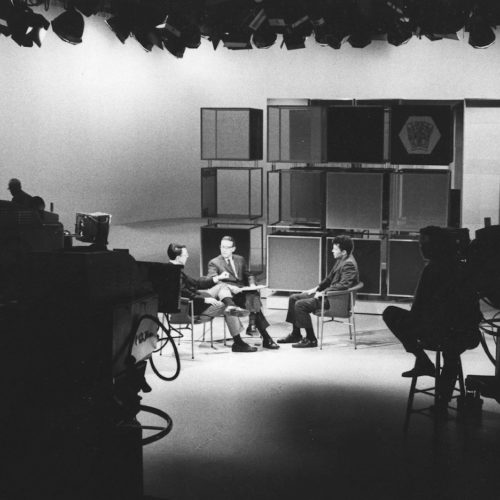

Photos: The Road to Public Television

Enter Ford’s Millions

The Ford Foundation, the largest American foundation at that time, funded new stations, underwrote specific programs, and helped establish a coordinated network of non-profit program distribution.

Ford had blazed onto the American scene in 1950, around the same time that television was beginning to gain momentum. Henry Ford’s will transferred 90% of Ford Motor Company nonvoting stock to the Ford Foundation as a means of avoiding a $300 million inheritance tax and the potential loss of family control over the Ford Motor Company. This windfall instantly transformed the previously modest family foundation into the nation’s largest. And this was by a very wide margin, with Ford assets exceeding those of all other US foundations combined.Francis X. Sutton, “The Ford Foundation: The Early Years.” Daedalus Vol. 116, No. 1, Philanthropy, Patronage, Politics (Winter 1987), pp. 41-91.

Opportunities in Mass Media

As the new foundation put its program together, it began to develop a domestic agenda that mobilized education to narrow economic and social gaps. Its study committee produced a set of recommendations known as the Gaither Report. That report specifically urged the Foundation to consider the opportunity posed by the mass media, positing that it could play

a profound role in the general education of youth and have an effect in many instances more powerful than that of our schools themselves.

Gaither Report, 1949.Op.Cit. “The History of Ford Foundation Activities in Non-Commercial Broadcasting,” September 1974. Ford Foundation Records, Catalogued Reports, Report #002027, Rockefeller Archive Center. The Gaither Report came out of nearly two years of interviews and studies. See Ford Foundation records, Papers of the Study for the Ford Foundation on Policy and Program (Gaither Commission), Rockefeller Archive Center.

Establishing Public Television Stations

National Educational Television (NET), launched in 1952 by the Fund for Adult Education (a fund established by the Ford Foundation), acquired and distributed programming to these public stations, as well as provided grant funds for local production, technical assistance, training, and publicity. Between 1952 and 1963, Ford entities supported NET with roughly $25 million. Throughout the 1960s, Ford support to NET averaged $6-7 million annually.Marilyn A. Lashner, “The Role of Foundations in Public Broadcasting, II: The Ford Foundation,”Journal Of Broadcasting, Spring 1977, p. 243. Ford Foundation Records, Catalogued Reports, Report #016765, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Following the federal government’s reservation of noncommercial bandwidth, from 1952-1961 the Ford Foundation made approximately $3.5 million in grants to 37 community organizations for the establishment of public television stations. Independent and non-commercial stations in major markets bloomed, including San Francisco’s KQED (first broadcast 1954), Boston’s WGBH (1955), Chicago’s WTTW (1955), Washington D.C.’s WETA (1961), and New York’s WNDT (1962).

Many other stations were smaller, run out of colleges, high schools, and bare-bones local facilities. After the Educational Facilities Act of 1962, the federal government began underwriting station construction and Ford grants for this purpose were phased out, and the Foundation turned its attention more robustly to grants for programming.

Two other foundations made essential contributions to public television as well. First, the 1965 Carnegie Corporation blue ribbon panel accomplished significant policy work. Its 15-member commission of highly visible, influential academic scholars, business leaders, and media professionals issued a final report titled Public Television: A Program for Action, offering a detailed vision that was a veritable blueprint for the establishment of PBS, National Public Radio, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Thus, the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television more or less directly enabled the passage of the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act.

“Creative Risks” via Public Television

That 1967 Act established the Public Broadcasting System we recognize today, which turns 50 in October 2020. The Act’s language clearly articulates the connection between public media and social justice, establishing the contours of both audience and content that would become public television’s hallmark:

It is in the public interest to encourage the development of programming that involves creative risks and that addresses the needs of unserved and underserved audiences, particularly children and minorities.

Public Broadcasting Act, 1967Public Broadcasting Act, Subpart D, Section 396, Item 6.

Shortly after the Act’s passage, a second foundation became deeply engaged with public television, when former Carnegie executive Lloyd Morrisett struck a partnership with documentary film producer Joan Ganz Cooney, who had chaired the Carnegie study. Together, they founded the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) and its flagship program, Sesame Street. In 1969, the year that Sesame Street premiered, Morrisett became president of the John and Mary Markle Foundation. He helped Markle launch a comprehensive program of ongoing support to CTW and other educational television endeavors.Markle Foundation records, Record Groups 1 and 2, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Until that point, educational television for children had consisted of the dry instructional fare usually viewed inside the classroom. To be sure, commercial television offered popular fare, such as Howdy Doody, Romper Room, Captain Kangaroo, and Bozo the Clown, some of which included instructional elements. But entertainment value and promoting the products of corporate sponsors were much more essential to these shows.

A New Era for Children’s Television

Much anticipated in the press, Sesame Street marked a new era in children’s television and boosted the cause of public programming generally. Whether it achieved its lofty goal to close the learning gap between children of privilege and their less-resourced peers has been debated ever since. Nonetheless, it succeeded in reaching a broader audience than public television had ever managed before. And it changed American culture, with its characters, songs and sketches becoming almost universally recognized to anyone born after 1965, prompting dozens of imitators, and quite literally changing educational television forever.

Further Reading

- Allison Perlman, “Re-envisioning Public Broadcasting: The Ford Foundation and the Public Broadcast Laboratory.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2025.

Related

Programming for the People: Diversity in Early Public Television

Philanthropy helped carve out a public space for the expression of race, culture, and critical perspectives.