Developing the first Hangul (Korean) dictionary was no small venture. In fact, the Korean-born project eventually came to fruition after ten years of development during political upheaval, widespread cultural repression, staff imprisonment, and all-out war. One unlikely partner in the publishing project was the Rockefeller Foundation, and the story is revealed through that institution’s archives.

“Korea has no Korean dictionary”

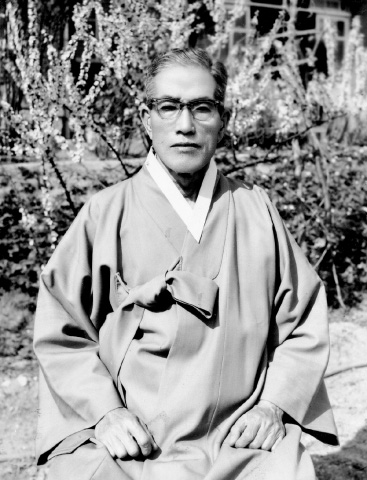

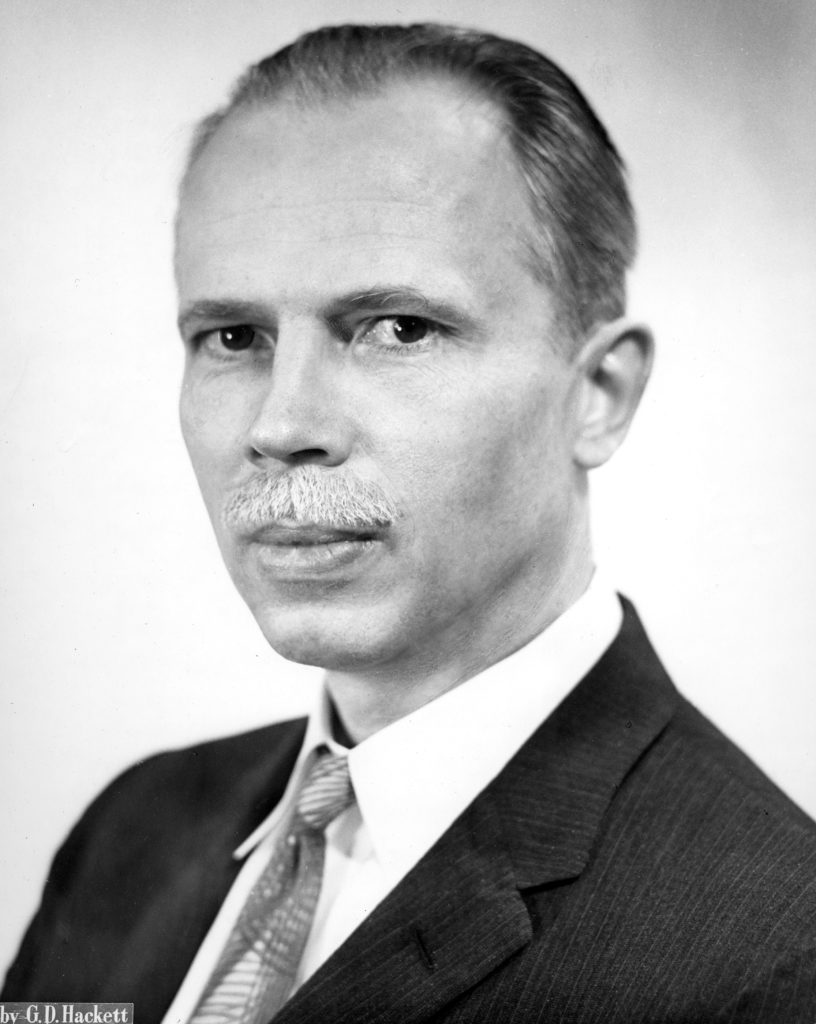

On June 12, 1947, Charles Burton Fahs, Assistant Director of the Humanities Division of the Rockefeller Foundation (RF), was more than halfway through his three-month survey trip to the Far East. He had just finished touring various institutions and locations in the Philippines, China, and Japan, to observe the effects of World War II and the initial stages of reconstruction and rehabilitation. Fahs flew to Korea for a brief week-long visit. In his diary, Fahs recounted his activities on the morning of June 12th, beginning with making a visit to Paul Anderson, a member of the United States Education Staff in Korea. Anderson, in turn, introduced Fahs to a man named Choi Hyon Pai (최 현배).

Choi has worked for twenty years on Korean language studies – grammar, a dictionary, standardized pronunciation, and simplified spelling. Korea has no Korean dictionary (i.e. no Korean-Korean dictionary), work in the Korean language having been discouraged by the Japanese as nationalistic.

Charles Fahs, 1947Entry for “June 12, 1947,” Fahs Diary, April 8-May 23, 1947, RG 12, Rockefeller Foundation Records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Choi was merely one of the twenty-five individuals that Fahs met with on June 12th; Choi’s personal history and the ongoing Korean dictionary project merit just six sentences in the officer’s diary for that day. Yet out of this brief encounter, a ten-year relationship developed, wherein Fahs, Choi, and others labored to produce the first complete dictionary of the Korean language for use by the people of Korea.For an account of the attempts and creation of the dictionary from the Korean perspective, see Park Yong-Gyu, “Historical Meaning of the Compilation,” The Archivist (National Archives of Korea), vol. 35, (Summer 2016).

Origins of the Korean Aphabet

King Sejong is credited with the creation of the Korean alphabet in the 1400s. Originally known as Hunminjeongum (훈민정음), it was also called the Eonmun (언문). Beginning in the early 20th century, it began to be regularly referred to as Hangul (한글). In the centuries following Hangul’s creation, the general preference for the use of Chinese characters in scholarly works was a contributing factor to the lack of a dictionary.

During the late 1800s, Korean-French and Korean-English dictionaries were produced to aid religious and cultural communication. In 1920, under the Japanese occupation of Korea (1910-1945), the Japanese Government-General of Korea created a dictionary for its own use.

The Korean Language Society

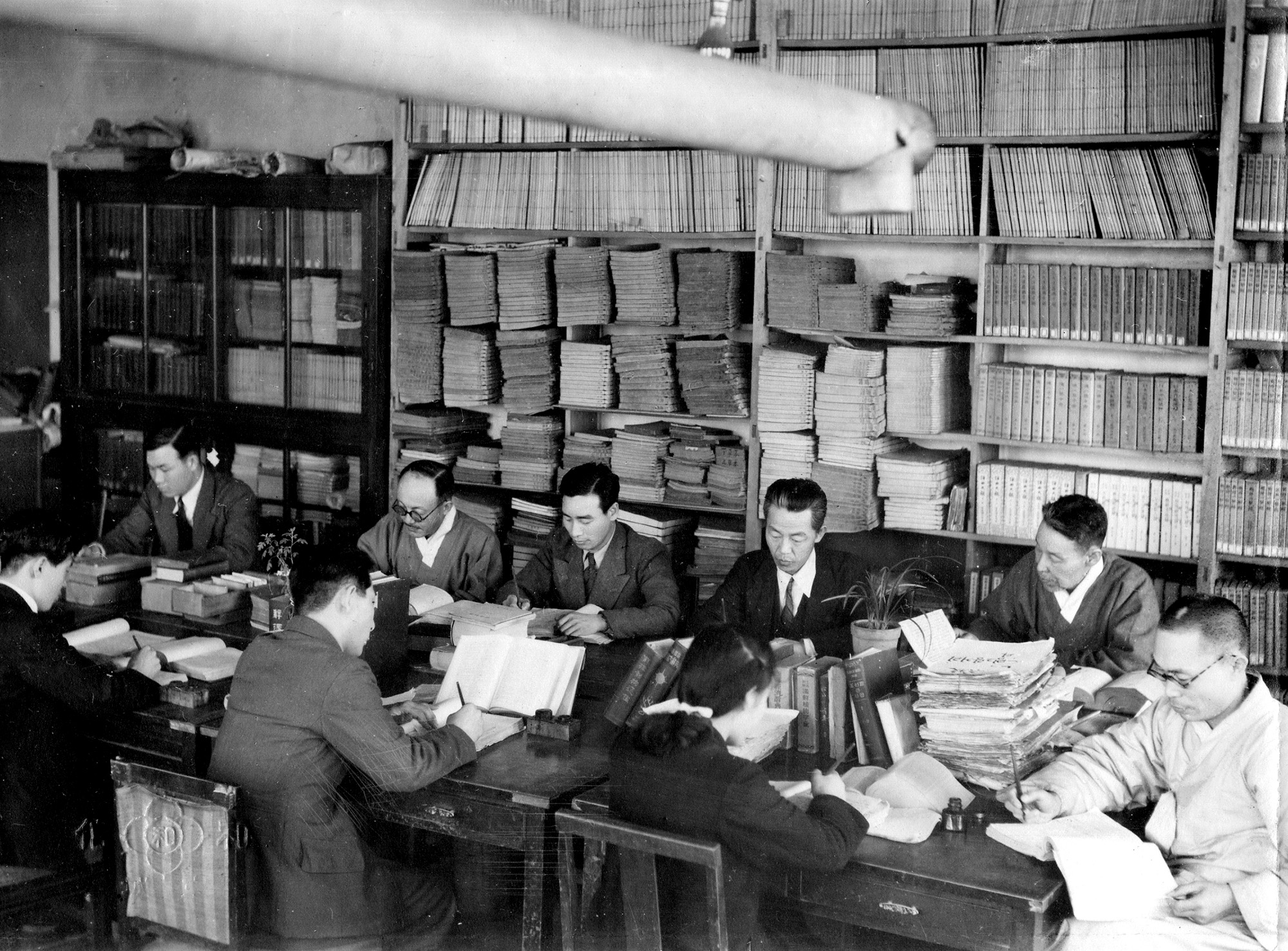

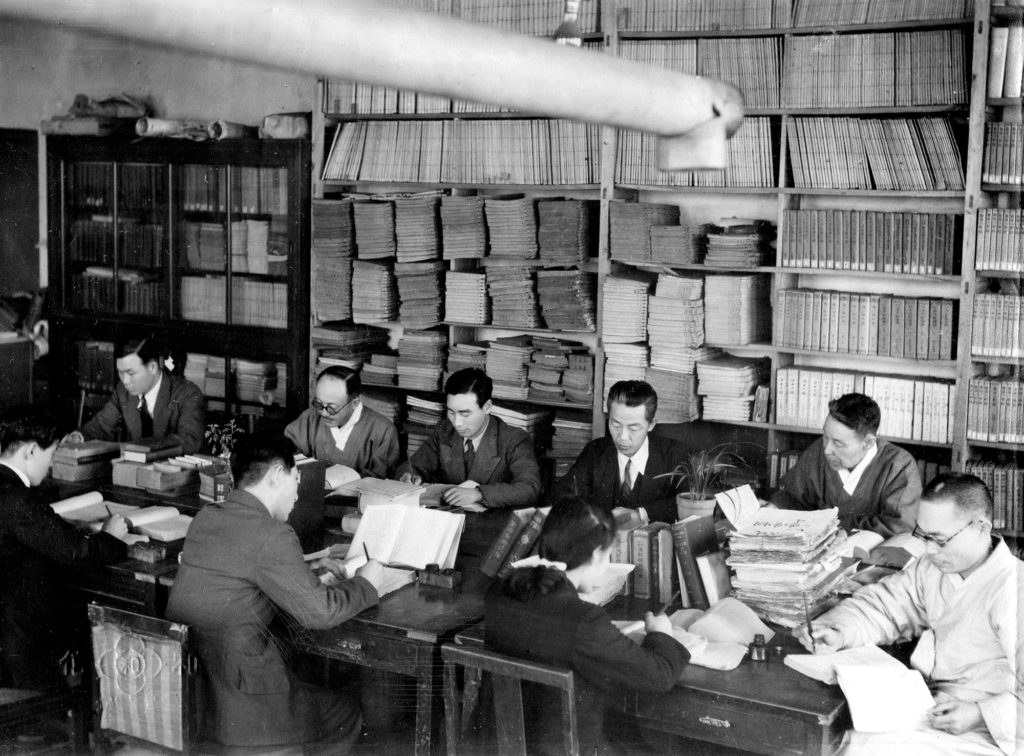

During the 1920s and 1930s, various groups formed to research, standardize, and produce a dictionary in Hangul, for Hangul. One such committee was the Korean Language Society (조선어학회), founded in 1921 (also called the Korean Language Research Society). As Fahs related to one of his Rockefeller Foundation colleagues, the Korean Language Society was “a group of over three hundred scholars which was organized during the earlier and more liberal period of Japanese occupation.”Fahs to Stevens, “Suggested Oral Presentation for Korean Dictionary Project,” March 31, 1948, Series 613 R, RG 1.2, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Anti-Hangul Repression

Choi Hyon Pai served as one of the directors of the Society, which experienced heightened persecution during the later years of the Japanese occupation of Korea, when the colonial government imposed strict anti-Hangul policies. “In the latter years…the work of the Society was forbidden, and during the war its members were arrested,” Fahs noted.Fahs to Stevens, “Suggested Oral Presentation for Korean Dictionary Project,” March 31, 1948, Series 613 R, RG 1.2, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center. The situation was so dire that thirty-three directors of the Society served jail terms under the Japanese.Fahs diary excerpt, April 10, 1952, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Despite the dangerous political climate, however, the Korean Language Society continued its work. They sought to produce a dictionary which would reflect clear, standardized spelling and syntax.

Investigating an Opportunity for the Foundation to Help

Upon his return to the States, Fahs began to explore what role the Rockefeller Foundation might play in the Korean dictionary project. Because the issue was not the creation of a dictionary but rather the publication of it, questions surrounding possible support were more practical than theoretical. Nevertheless, an added layer of complexity was the need for cooperation amongst the Korean Language Society, the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK), and the Foundation.

Fahs met with Anderson again, this time on American soil, on December 2, 1947. Anderson reported that, despite hopeful attempts, he had been unable to secure any sort of military government funding for the project. Anderson feared that publication would likely be “indefinitely postponed” if forced to rely solely on donations from the Korean people. Although Volume I of the dictionary had recently been published, nearly all Korean funds and supplies for the project had been used in the process – and yet, four volumes were still forthcoming. In fact, Anderson noted, copies of the first volume “exhausted the open or black market supply of paper.”Anderson to Fahs, December 3, 1947, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Writing again in his officer’s diary after this meeting, Fahs reflected on the significance of the project to the US government.

Anderson emphasized that completion of the Dictionary is essential to many of the programs of the military government in Korea despite inability to help.

Charles Fahs, 1947.Fahs diary interview, December 2, 1947, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

This is because the dictionary, which included a standard guide on spelling and pronunciation, would be of invaluable help to the US Army’s Office of Education textbook program. The textbook program was part of a larger reestablishment of the Korean educational system, which was in shambles following the Japanese occupation and World War II. Schools had closed, and over 40% of all teaching positions in the elementary schools, secondary schools, and colleges and universities were vacant, previously filled by Japanese personnel. The lack of “standardization as to spelling, pronunciation and in some cases meaning” hindered the USAMGIK’s Korean textbook program. Fahs diary interview, December 2, 1947, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Anderson reiterated the project’s importance as he closed his letter of December 3rd:

A grant of material from the Rockefeller Foundation that would make possible the distribution of this material would be a major contribution to the rebirth of the Korean nation.

Charles Fahs, 1947.Fahs diary interview, December 2, 1947, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Collecting Expert Opinions

Although the dictionary seemed to be of great value to the US Army Military Government in Korea, and of interest to the Rockefeller Foundation’s Division of the Humanities, Fahs sought out additional expert opinions. Having obtained a copy of the first volume, he contacted two colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley. From George McCune of the Department of History and a former RF fellow, he requested an opinion “with regard to its quality and its importance.”Fahs to McCune, December 3, 1947, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.From Samuel Farquhar, Director of UC California Press, he asked for advice regarding the amount and types of supplies needed for publication. Recent developments meant that the dictionary was now projected to comprise six volumes.

McCune reported back to Fahs with his opinion of the dictionary. Although not greatly impressed upon first review, he nonetheless relayed to Fahs his final verdict:

After considerable thought on the subject, I have concluded that this dictionary represents an enormous stride forward in Korean lexicography and that as such it deserves high praise…It is particularly important that a dictionary of this sort be published at the outset of the rebirth of the Korean language, so that a correct start be made in native writing.

George McCune, 1947.McCune to Fahs, February 10, 1948, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

From discussion with Farquhar on the most appropriate printing materials and estimates of supply, Fahs began to formulate what shape RF support could take. Farquhar believed that it would likely be best to purchase the materials in the United States and ship them to Korea, rather than to try to procure them abroad.

In preparation for adding the Korean Dictionary Project to the docket for the June 1948 Board of Trustees meeting, Fahs shared a draft with David H. Stevens, Director of the Humanities Division. There Fahs noted that the proposal was only for materials which were not available to Koreans due to restrictions imposed under the US occupation. Fahs saw nothing but benefit in RF support of the project:

It is seldom that an opportunity occurs to aid a project which represents first-class scholarship, has at the same time such basic and broad general significance and, without being political in character, has such important symbolic implications for the growth both of cultural nationalism and of good relations with the United States.

Charles Fahs, 1948.Fahs to Stevens, “Suggested Oral Presentation for Korean Dictionary Project,” March 31, 1948, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Grant Funding Comes Through for the Korean Dictionary

At the June 18, 1948 meeting, the Executive Committee appropriated $45,000 “to provide essential materials to enable the Korean Language Society to publish 20,000 copies each of the five unpublished volumes of its new dictionary of the Korean language.”Grant Action, June 18, 1948, Series 613 R, RG 1.2, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.The grant terms stipulated that all funds were to expire by December 30, 1950. The Society gratefully and enthusiastically responded that they would do their utmost to complete publication before that date.

Fahs established contact with the Society as well as with the Eul-yu (also known as Eu Ryu or Ul-yu) Publishing Company and its representative, Minn Pyung Do. Typesetting began almost immediately. The first batch of supplies arrived in the late fall of 1948, with transport and delivery within Korea supplied by the US Army. Volume II of the dictionary became available to the Korean public on June 10, 1949, and by September 30th, printing of the third volume was in progress.

Progress, Despite Setbacks

In April 1950, Fahs returned to Seoul on another of his trips to Asia. He met with the publisher, Minn Pyung Do, who explained that electrical outages caused delays in Volume III’s publication. (“South Korea has never recovered from the effects of the cutting off of power from the Soviet zone,” observed Fahs.)Fahs diary excerpt, April 18, 1950, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.Despite the delays, and an occasionally prickly relationship between the publisher and the Society, Fahs wrote that he was “relieved to learn that there was nothing seriously wrong with the dictionary project.”Fahs diary excerpt, April 18, 1950, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

While in Seoul on April 25th, Fahs attended a dinner as a guest of the Korean Language Society. At the meal, Fahs learned that all in attendance had spent between one and four years in prison under the Japanese as a direct result of their work on the dictionary manuscript. The group shared that Volume III’s publication was imminent, Volume IV was in press, Volume V was in manuscript, and Volume VI was in the last stages of editorial work. Thanks to the Rockefeller Foundation funds, the Society reported, purchase prices for the volumes could remain reasonable.

The Korean War Breaks Out

Exactly two months after that celebratory dinner, on June 25, 1950, the Korean War began with the North Korean communist invasion of South Korea.

Fahs and the Rockefeller Foundation received no communication from the Korean Language Society for nearly a year.

Finally, in late March of 1951, Fahs received a letter from Choi Hyon Pai of the Society. In it, Choi wrote a brief account of his experience.

It was early dawn on the 25th of June 1950 that the Communist invaders of North Korea opened fire, and early in the morning of the 28th we found ourselves enclosed by the enemy forces with honking and clanking tanks and glittering bayonets. Every property in Seoul was either ravaged or destroyed by these aggressors. It was obvious, therefore, that a great loss incurred upon our property was also inevitable.

Choi Hyon Pai, 1951.Choi to Fahs, March 16, 1951, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Because of the invasion and occupation, nearly all the Society members had had to flee Seoul. Many found refuge in the city of Pusan (Busan), along with the publisher, Minn Pyung Do.

Several months later, Choi and Minn returned to Seoul to assess the damage. For both the Korean Language Society and Eul-yu Publishing, the losses were great. Some members of the Society had been taken away by the Communists and the printing office had been set on fire. Choi related that South Korean and United Nations forces reported that the 410 reams of paper for the dictionary volumes “were used by the Communists to take photographs of Stalin and Kim Il-song, and to print propaganda posters.”Choi to Fahs, January 20, 1952, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Korean Dictionary Texts Saved…in Pickle Jars

Yet all was not lost, Choi maintained. When the invasion began, he took portions of the manuscripts and put them into large pots or pickle jars, burying them in the ground. The addition of charcoal mitigated moisture in the pots. “After September 28,” he wrote, “we took out these pots and aired the manuscripts.”Choi to Fahs, January 20, 1952, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

After that experience, the Society members felt that an extra copy of the manuscript was merited, “as we felt that the war might fall into a worse situation.”Choi to Fahs, January 20, 1952, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center. For 40 days, five men worked steadily to copy the manuscript by hand. For safekeeping, they sent this copy to the remote village of Chung-chong in the south, the hometown of one of the compilers. When the second Communist invasion of Seoul occurred, Choi employed the same burying method to conceal the manuscript.

[W]e took out these pots and aired the manuscripts.

Choi Hyon Pai, 1952

A Renewed Effort to Publish

In April 1952, Fahs again returned to Korea. On this visit, he was based in Pusan. He met with Choi and Minn, and discussed the possibility of renewed support from the Rockefeller Foundation. This time, the Foundation would need to coordinate with the United Nations Korean Reconstruction Agency (UNKRA) regarding material acquisitions and shipments. Unlike the US Army, UNKRA was initially reluctant to assist with logistics. However, in the following months, the Agency opted to allocate $37,000 towards the dictionary publication work.

Before bringing a recommendation to the Board of Trustees meeting in December 1952, Fahs explored the feasibility of completing the publication in Japan. There, supplies and infrastructure would already be in place, and thus easier to coordinate. In September, publisher Minn Pyung Do visited Tokyo using a $350 travel grant from the Foundation. Following his visit, he sent along two estimates from Japanese publishing companies.

Based on Minn’s estimates, on December 3rd the Board of Trustees allocated $33,000 toward the costs of the dictionary. As with the original grant, this was only to cover the costs of supplies; this time, the remaining volumes would be published in Japan. Ironically, the very nation that had earlier repressed the Korean language seemed now to be the key to promoting it.

By late March 1953, it appeared that the final pieces were falling into place with the Japanese printing company and UNKRA.

Opposition and Persistence

However, on April 28th, Robert McClure of UNKRA telephoned Fahs with some bad news.

[He] had learned in Korea that President Rhee had objected to the dictionary project on two grounds: first, he would not approve printing in Japan (there is still no peace treaty between Japan and Korea) and, second, apparently he is now inclined to reject the modern orthography adopted by the Korean Language Society and to revert to the old system.

Charles Fahs, 1953.Fahs diary excerpt, April 28, 1953, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

At this juncture, the potential withdrawal of the $37,000 UNKRA allocation, along with the high-level opposition, placed the entire project in jeopardy. McClure suggested to Fahs that the Rockefeller Foundation withhold funds for at least six months. “After 6 months the situation might change and a request for additional funds from UNKRA can be made again.”McClure to Zarjevski, forwarded to Fahs, April 27 and 29, 1953, Rockefeller Foundation records (FA387b), Rockefeller Archive Center.

During the summer of 1953, Minn Pyung Do visited the United States, meeting Fahs in New York on July 27th. Fahs explained the issue with the grant terms. The Trustees would need to vote to amend the terms of the grant; otherwise, the funds would expire. Minn’s sense was that the objections to the spelling system were not insurmountable and would likely be overcome. Still, in September of 1953, Evelyn McCune of UNKRA wrote to Fahs, “this project has had so many ups and downs that it will be a miracle if it ever comes to completion.”McCune to Fahs, September 25, 1953, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center. (The original copy was lost in the mail; a copy was handed to Fahs in person when in Korea in May of 1954.)

In May of 1954, Fahs again visited Seoul, learning more about President Rhee’s continued objections to printing the dictionary in Japan and to using modern orthography. Although shifting publication back to Korea could perhaps solve the first issue, Rhee’s objection to the revised system of orthography long endorsed by the Society presented a larger problem. It meant that the entire dictionary would need revision, despite the near-universal support of Korean scholars for the Society’s system. The previous Minister of Education had resigned over this very issue, and his position remained vacant for three months.

It will be a miracle if it ever comes to completion.

McCune, 1953.

At a meeting with Society members, Fahs learned that even the cabinet ministers wished to keep the present orthographical system in place. The members present at the dinner “attributed the President’s attitude to the fact that he and a few cronies who, like him, lived in Hawaii most of their lives, are about the only Koreans who have not learned the Hangul Society spelling.”Fahs diary excerpt, May 4, 1954, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center. Despite the deadlock, and the consequent inability to access Foundation funds, Choi remained resolute:

[Choi] made it quite clear that having fought for the dictionary through twenty years of Japanese occupation, three years in a Japanese prison, and two Communist invasions, he didn’t propose to give up at this point.

Charles Fahs, 1954.Fahs diary excerpt, May 4, 1954, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

As Marcus Scherbacher from the US Embassy in Seoul put it, “If there is any man in Korea as stubborn as President Rhee it is Mr. Choi, President of the Language Society.”Fahs diary excerpt, April 2, 1956, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Full Steam Ahead

At long last, over a year later, Fahs received some positive news from Choi. President Rhee had announced that he would no longer seek to influence the issues with Korean spelling. Given this, Choi wondered whether the Foundation would again look favorably on the project. As the previous grant had lapsed, Fahs needed to approach the Board for approval all over again.

After several months of renewed discussions of printing facilities, material estimates, and negotiations of quantities, Fahs felt prepared to bring the item before the Board. On April 4, 1956, the Trustees allocated $36,000 to provide materials for the publication of the six-volume dictionary. This time, plans were in place to ship supplies to Korea through the American-Korean Foundation.

By January 1957, the supplies had arrived in Korea. Over the next several months, the remainder of the volumes were published. Copies of the six-volume dictionary were sent to a variety of institutions in the United States (UC Berkeley, Columbia, Harvard, Library of Congress, and others), Hong Kong, England, France, and Taiwan.

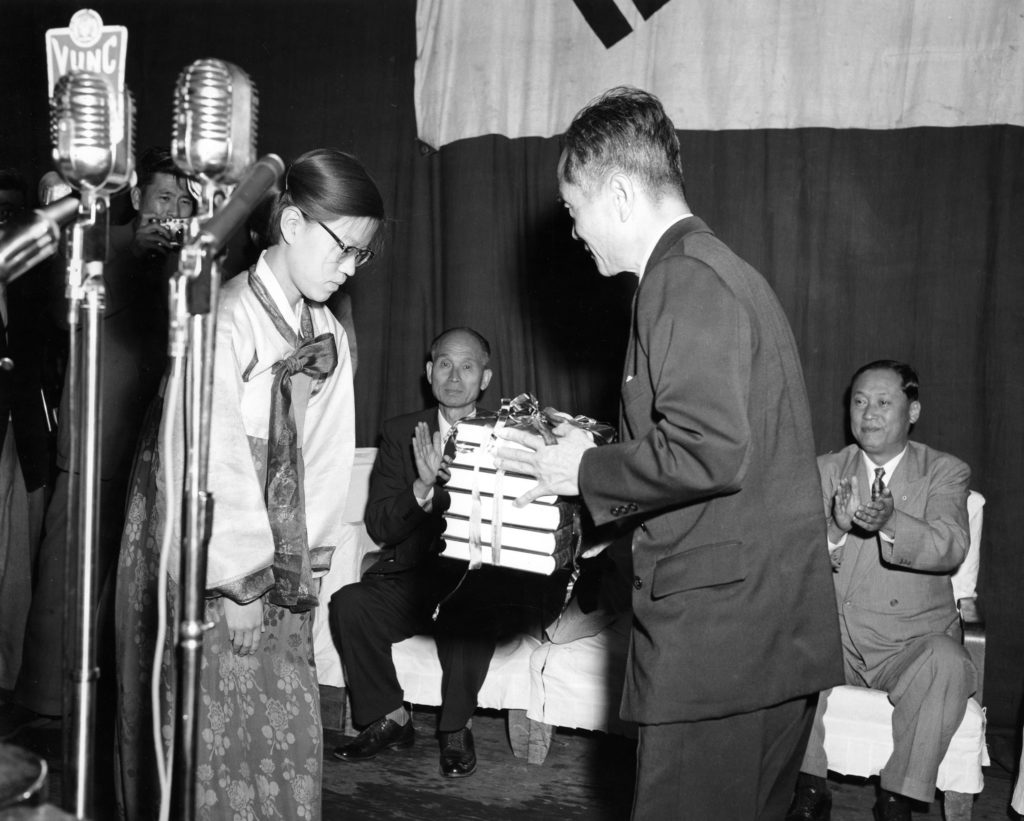

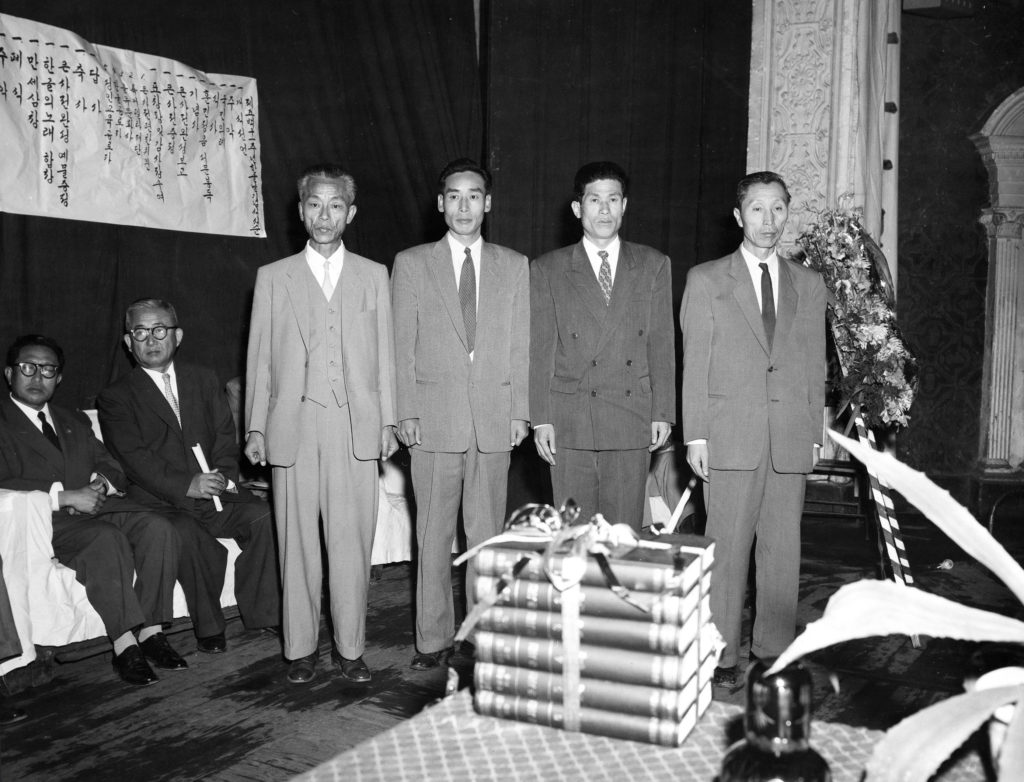

On October 9, 1957, South Korea celebrated Hangul Day. The holiday, observed since the 1920s, recognizes the creation and promulgation of the Korean alphabet. That year, for the first time ever, the first comprehensive Hangul dictionary had a place in the celebrations. Scherbacher from the US Embassy accepted an official citation from the Korean Minister of Education on behalf of the Foundation. Over 2,000 people attended the ceremony, held at the City Theater.

A Satisfying Ending to an Unlikely Foundation Project

For ten years, Fahs and the Rockefeller Foundation engaged with and supported the Korean Language Society in their quest to publish the first comprehensive Korean dictionary. Interestingly, from the start the project itself diverged from Foundation policies. Fahs wrote in 1949 that “the grant which was made for the Korean dictionary was an almost unique exception to a long-standing practice of not assisting publications.”Fahs to Werth, November 22, 1949, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Nevertheless, this project dovetailed nicely with existing Foundation programs in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The Foundation’s ongoing interest in the development of area studies, including Far Eastern/Asian Studies, likely influenced the decision to make this outlier grant. Similarly, Humanities projects in postwar Asia reflected a commitment to work in languages, libraries, and literature. Although a deviation from usual Foundation policy, the Korean Dictionary Project was nonetheless representative of RF interests in the region.

On October 10, 1957, Choi Hyon Pai wrote to Fahs once again. The letter, accompanied by some articles about the dictionary, expressed Choi’s deep thanks to Fahs and the Foundation for their persistent support over the years.

Needless to say, this is one of the epoch-making events in our cultural history and we owe this to you very much.

Choi, 1957.Choi to Fahs, October 10, 1957, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

His statement echoes those found in earlier Foundation grant action documentation. “In addition, in the course of its many vicissitudes the dictionary has become in part a symbol of the movement to build a Korean culture free from foreign domination.”Grant Action, April 4, 1956, Rockefeller Foundation records, Rockefeller Archive Center.

…to build a Korean culture free from foreign domination…

Rockefeller Foundation Grant Action, 1956.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “Korean Language Society – Korean Dictionary,” 1947-1959, Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants) RG 1, SG 1.2, Series 300-833, Latin America, Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceania, Korea, Series 613, Korea – Humanities and Arts, Subseries 613.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Korean Language Society – Korean Dictionaries,” 1949 and 1957, Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Series 100-1000, Korea, Series 613, Korea – Humanities and Arts, Subseries 613R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “D68a: Letter of appreciation: Korean Language Research Society,” 1958, Rockefeller Foundation records, Non-Textual Materials, RG 19, Decorations, SG 19.1, Subgrp 19.1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Trip to the Far East,” 1954, Rockefeller Foundation records, Officers’ Diaries, RG 12, F-L, Fahs, Charles B., Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Trip to Korea,” 1958, Rockefeller Foundation records, Officers’ Diaries, RG 12, F-L, Fahs, Charles B., Rockefeller Archive Center.