Business education as it exists today came out of a massive mid-century philanthropic effort to transform the field. Why would an American foundation take this on and what was the program’s impact?

Mid-Century Bureaucratic Ideals

A new philanthropic giant, the Ford Foundation, came onto the scene in a big way in 1949. That year, Ford was the largest American foundation ever to exist, and was on track to become the first billion-dollar foundation. After an intensive study period looking at how such a great fortune could be put to use to solve world problems and social concerns, Ford trustees approved a strategy that prioritized peace and prosperity through democracy and economic development.

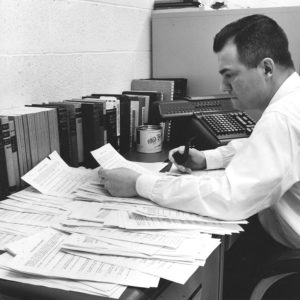

Throughout the post-war economic boom, the notion prevailed that a rising tide would lift all boats. Ford leaders were looking for ways they could encourage economic growth and stave off the negative aspects of economic cycles. Bureaucratic efficiency was everywhere evident, indeed characterized the cultural fabric of the times, but a real theory of business practice was absent.

In 1954, Ford began what would later be deemed a “revolution” in American business education, launching the development of the Master of Business Administration as we know it today.

Ford Vice President Thomas Carroll, who had received his PhD from the Harvard Business School, was one of the Ford staffers leading the charge. More influential than personal staff interest, however, were strategic and programmatic reasons to support business education, a field that had been overlooked by foundations and rigorous academic study alike. Ford’s Program in Economic Development and Administration (EDA) had been set up in 1953 under the guiding assumption that “economic well-being does not assure human welfare, but it is essential to it.” Program in Economic Development and Administration, “Evaluation and Statement of Current Objectives and Policies,” (December 1961), 1. Report #004741, Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

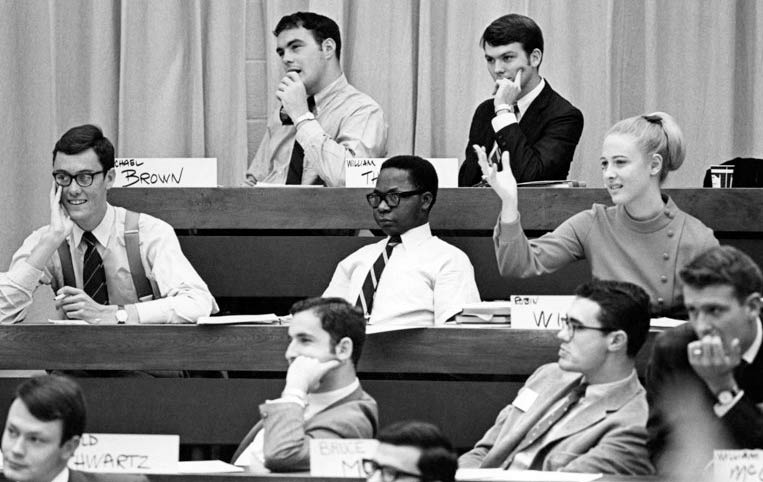

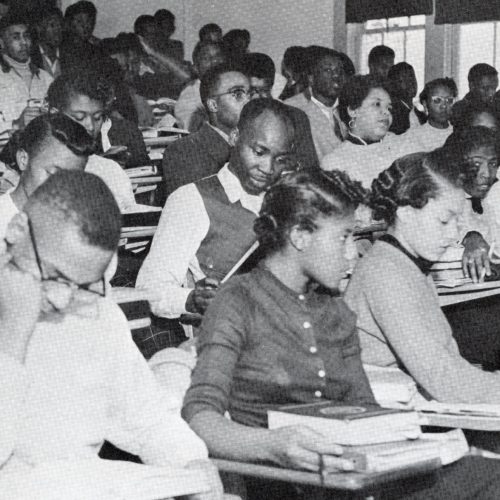

Although many elites recognized the business sector as central to American economic prosperity, business education at this time was by and large vocational. Programs focused more on the day-to-day operations of business, not on underlying fundamentals such as economic cycles, statistical analysis, consumer behavior, etc. Furthermore, even the most rigorous programs, such as Harvard’s (where the case study method and the MBA had been invented in 1908), had difficulty attracting top students.

An internal Ford memorandum described business schools as “unimaginative, non-theoretical faculties teaching from descriptive, practice-oriented texts to classes of second-rate, vocationally-minded students.” Internal memorandum cited in James E. Howell (September 1966), 3-4.One document from 1957 put it more bluntly: the Ford program was trying to bring about the “intellectualization” of business education.“‘Big Push’ in Business Schools,”(October 1957) 1. Report #002971, Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center. Internal memorandum cited in James E. Howell, (September 1966) 3-4.

Something else motivated Ford trustees and staff: a flashy philanthropic program to help the private sector could make for good public relations. On the heels of the early 1950s congressional investigations into foundations, with their attacks on the “liberal” Ford Foundation, and with intimations of communist sympathizing in the conservative press, the focus on business would testify to Ford’s commitment to both democracy and the free market within the Cold War context.

To public relations conscious trustees and officers, the proposed program in business education was indeed welcome.

James E. Howell, reflecting back on the program in 1966James Howell, “The Ford Foundation and the Revolution in Business Education: A Case Study in Philanthropy,” (September 1966) 2. Report #006353, Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Business Education: From Practice to Theory

The “big push” in business education, as Ford staff came to dub the new program, first targeted the supply of qualified faculty. Five large-scale grants created “centers of excellence” at Harvard, Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon), Columbia, Stanford, and the University of Chicago.

These centers — already elite institutions with model programs — received millions in support for research and doctoral training. Their highly-trained students would become the leaders of a network of business schools across the country. As a 1961 evaluation explained:

The purpose was not to help the rich grow richer, but to increase the supply of competent, research-oriented teachers of business administration who would be equipped with analytical habits and a command of the underlying disciplines.

Program Evaluation, 1961.Program in Economic Development, Evaluation (1961), 6.

Basic research firmly grounded in economics, statistics, mathematics, sociology, and psychology would contribute to building a theory of business practice. As Neil Chamberlain, an economist on Ford’s EDA team, put it: this theory would mean that “business schools may forge ahead of business practice and thus contribute to its development.” Neil W. Chamberlain, “Ford Foundation Activities in the Field of Business Education,” (1958) 2. Report #002970, Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

To spread the new curricular approach to the six-hundred other business programs, Ford sponsored summer seminars and short training programs for faculty and deans.

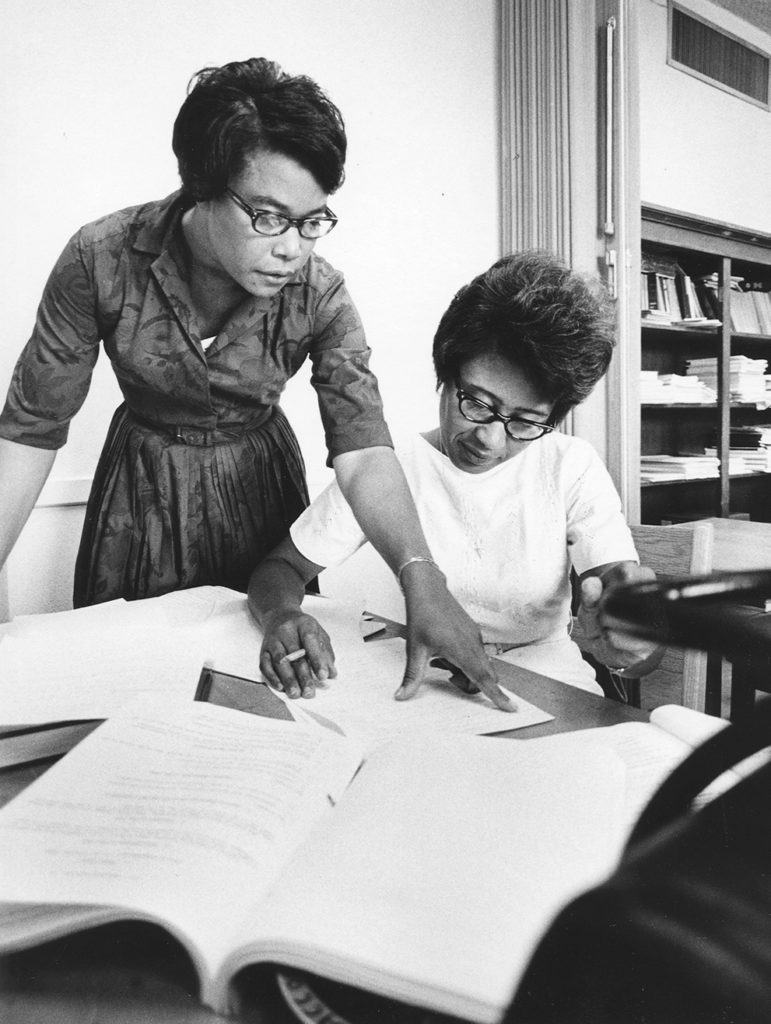

In parallel to its other efforts, Ford funded Robert Gordon and James Howell’s 1959 groundbreaking study of business education. The study argued that higher education should make students into problem solvers and ethical thinkers (Carnegie Corporation also funded a concurrent study that reached similar conclusions). To Gordon and Howell, business education should be career preparation, not just instruction on how to get through the day-to-day activities of your first job.

Gordon and Howell described an ideal business education as “a process of self-development, in which the student develops the capacity to see the relevance of what is being learned and to build on this knowledge an ability to deal with problems that he will meet in later years.”Robert Aaron Gordon and James Edwin Howell, Higher Education for Business (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959), 109.

Ford staff ensured the book was sent to every full-time business school faculty member in the country.

The MBA Becomes the Gold Standard

By 1965, Ford had spent $46.3 million on business education reform (approximately $375 million in 2019 dollars) — half of it to business schools, and the rest to fellowships, research projects, workshops, and publications.

Writing in 1966, James E. Howell called the Ford program a “revolution in business education.”James E. Howell, “The Ford Foundation and the revolution in business education: A case study in philanthropy,” (1966). Report #006353, Ford Foundation records, Catalogued Reports, Rockefeller Archive Center.

[The Ford Foundation] was the strategic force behind the reorientation of one of the largest sectors in American higher education; and it was by far the single most powerful force in bringing about that reorientation.

James E. Howell, 1966.James Edwin Howell, “The Ford Foundation and the Revolution in Business Education: A Case Study in Philanthropy” (1966), 27.

Research This Topic in the Archives

- “67. Economic Development and Administration Program (EDA) – Business leadership education,”

- “EDA Business Conferences,” 1958, Ford Foundation records, Administration, Office of Communications, Press Materials, Record Group 1, Accessions 2017:062 and 2017:078, Recordgrp 1, Press Releases, Series 1, News from the Ford Foundation Releases, No. 1-295, Subseries 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “B-799: Fellowship Program for Master of Business Administration (MBA) Graduates,” 1955-1956, Ford Foundation records, Central Index, Projects, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “The Ford Foundation and the revolution in business education (Reports 002591),” 1960, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 1-3254, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Ford Foundation activities in the field of business education (Reports 002970),” 1958, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 1-3254, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Gordon-Howell Report on Business Education – Robert Aaron Gordon and James Edwin Howell,” 1959, Ford Foundation records, Administration, Office Reports, Photographs, General, Program, and Project Photographs, Series 3, Economic Development and Administration (EDA), Subseries 3 2, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “The commonwealth: official journal of the Commonwealth Club of California, vol. 31, no. 12, March 21 (Reports 015068),” 1955, Ford Foundation records, Programs, Catalogued Reports, Reports 13949-17726, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Related

“Investment Philanthropy” Investing for Social Good, a Century Ago

An early twentieth-century foundation tried using its endowment to support for-profit projects that also would achieve a social goal.

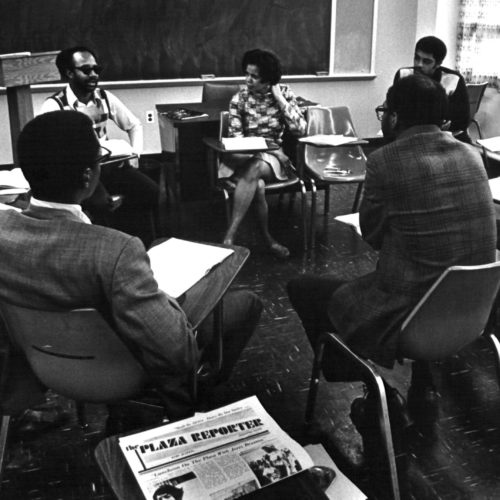

Photo Essay: Supporting Minority Enterprise in the late 1960s

In 1968, the Ford Foundation began to make social investments using a new tool borrowed from the for-profit world, the Program-Related Investment.

The Origins of the Rockefeller Foundation Equal Opportunity Program

How a simple grant request seeded the launch of a full program addressing inequality.

Supporting Economic Justice? The Ford Foundation’s 1968 Experiment in Program Related Investments

How the largest US foundation began supporting market-based projects in the late 1960s.