The century of biology upon which we are now well embarked is not matter of trivialities. It is movement of really heroic dimensions, one of the great episodes in man’s intellectual history. Do not be fooled into thinking this is mere gadgetry. This is the understanding of life.

Warren Weaver

The high point of the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) program in the natural sciences was its initiative in experimental biology, which ran from 1933 to 1951 under the leadership of Warren Weaver. Weaver is widely credited with coining the term “molecular biology” in 1938 to describe the work the Foundation had been supporting, and it was quickly picked up by the scientific community.

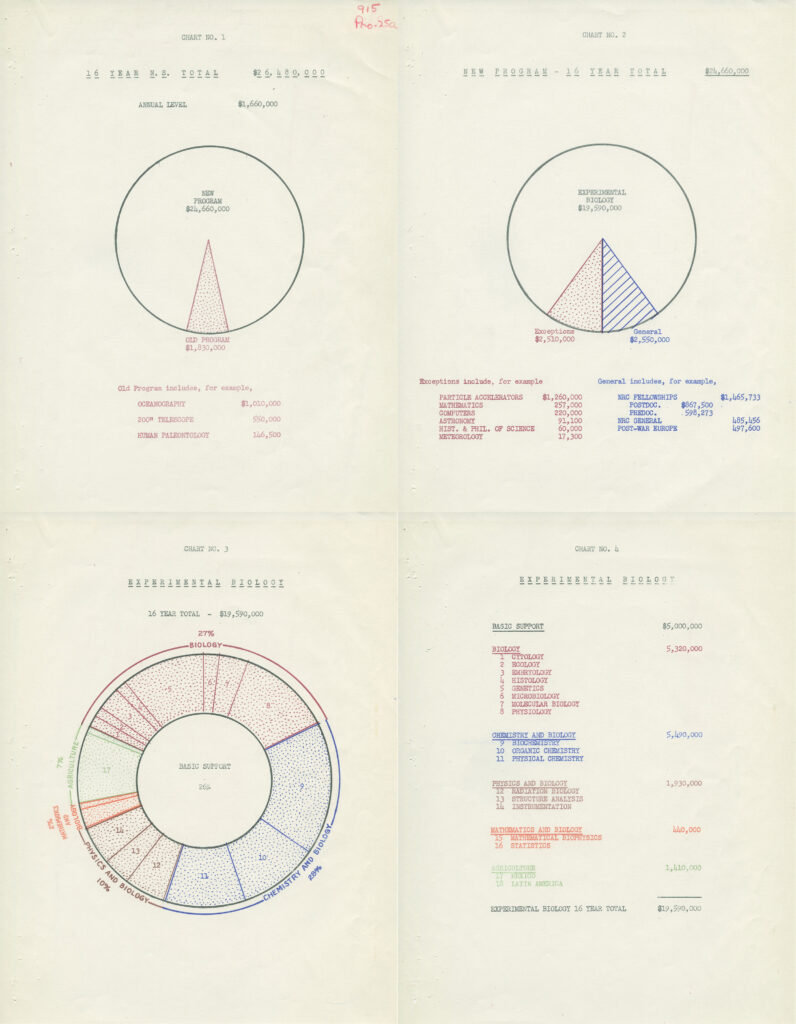

By the early 1930s, the RF had logged more than a decade of support for the physical sciences. It had helped build infrastructure in both physics and chemistry through direct grants to universities and research institutes, as well as extensive fellowship programs administered through the National Research Council (NRC) since 1919, and by the RF’s own International Education Board (IEB) since 1923.

The experimental biology initiative, however, made a more targeted contribution to the development of science. Its essential idea was that the better-developed tools of physics and chemistry could be applied to the as-yet-unanswered questions of the life sciences.

“Organized Complexity”

Warren Weaver advocated heavily for the development of an experimental biology initiative. After joining the Rockefeller Foundation in 1932, he quickly moved to define the mission of the newly established Division of Natural Sciences. Though a mathematician by training, he was well aware of recent technological advances in physics and chemistry, and undertook a program of self-directed study to help him converse with scientific researchers. As he surveyed the field, Weaver came to believe that the Foundation could distinguish itself by promoting similar advances in the biological sciences.

As he later explained, the physical sciences had successfully addressed both “problems of simplicity” involving limited variables, and problems of “disorganized complexity” involving billions of variables calculable in theoretical terms. But the life sciences represented a middle ground of “organized complexity” in which a medium-sized number of variables could not be separated from each other because the research question was biological. A watch spring, he illustrated, could be removed from its casing and studied for its own properties, but a human heart could not be similarly removed from a living organism.Warren Weaver, A Quarter Century in the Natural Sciences (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 1958) 7-10.

Building upon a network of institutional and personal contacts in the scientific community fostered by the IEB in Europe and the General Education Board (GEB) in the United States, Weaver and his staff proceeded to identify researchers whose work crossed disciplinary boundaries and persuaded them to tackle biological research. The California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the Universities of Copenhagen and Uppsala in Europe received major grants as part of the new initiative.

From “Vital Essences” to “Experimental Biology”

Throughout the early 1930s, the Division of Natural Sciences coordinated its efforts with the Division of Medical Sciences because both were ultimately concerned with bodily processes, including metabolism, genetics, disease, viruses, and cellular development. To avoid redundancies in program focus, the two divisions aimed instead to create a comprehensive “science of man” that would also contribute to the Foundation’s guiding principle adopted in 1928: “the advancement of knowledge.” By working together, they hoped to address the ill-defined relationship between the biological and the psychological–in short, to figure out as much about people as science had already discovered about physical matter. As Weaver asked, “Why do we seem to know so much more about atoms than we do about men?”“The Program in the Natural Sciences,” by Warren Weaver, March 1950, Rockefeller Archive Center, RG 3.1, Series 915, Box 2, Folder 14.

Striving to clarify the rationale behind technology transfer from the physical to the biological sciences, Weaver initially named the program “vital essences,” then later “experimental biology.” In 1938, having seen new technologies enable increasingly tiny units of measure, Weaver coined the term “molecular biology.”Warren Weaver, “Molecular Biology: the Origin of the Term,” Science, CLXX (November 6, 1970): 581-582. As he explained, this new hybrid science disputed the long-held view that “man as a conceiving, child-bearing, thinking, behaving, growing and finally dying organism presented problems that were in great part outside the range of rational analysis.”“The Science of Man,” November 29, 1933, by Warren Weaver, RAC, RG 3.1, Series 915, Box 1, Folder 7.

Molecular biology fit neatly within the Rockefeller Foundation’s strategic style in a number of ways. First, it was top-down science, since it relied on acquired expertise — a trained eye examining almost invisible particles, and a reliance upon precise and elaborate technologies. Second, it examined component parts in order to understand and eventually affect the larger whole, much as identifying “root causes” could change social problems. Third, in contrast to endowing entire institutions, funding this type of scientific research could be achieved through smaller, targeted grants, and this offered a measure of relief in the Depression-era climate of belt-tightening. Finally, program design required a managerial perspective that relied on educated hunches, strategic investments, and shrewd oversight — all qualities which Weaver possessed and cultivated in himself and his staff.

Why do we seem to know so much more about atoms than we do about men?

Warren Weaver

Science Along Particular Lines

Progress shot forward at a lightning pace as the Foundation’s’s interests and funding helped shape research agendas. Major efforts supported by the Foundation included Linus Pauling’s work on chemical bonds, George Beadle and Edward Tatum’s work on how genes govern metabolic processes, Alfred Kuhn’s work in evolutionary developmental biology, Boris Ephrussi’s work on the regulation of embryological processes, and Otto Warburg’s study of the fermentation of sugars in the development of cancer cells. The Natural Science division’s funds also supported research on photosynthesis, vitamins, and radiation therapy for cancer.

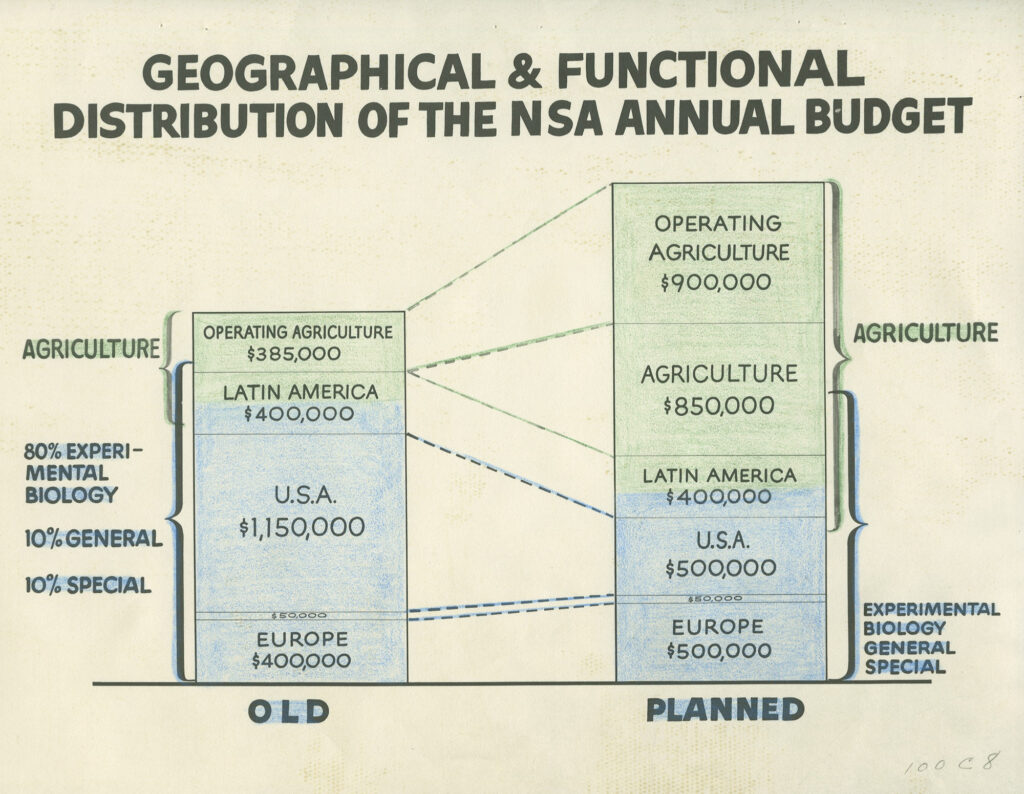

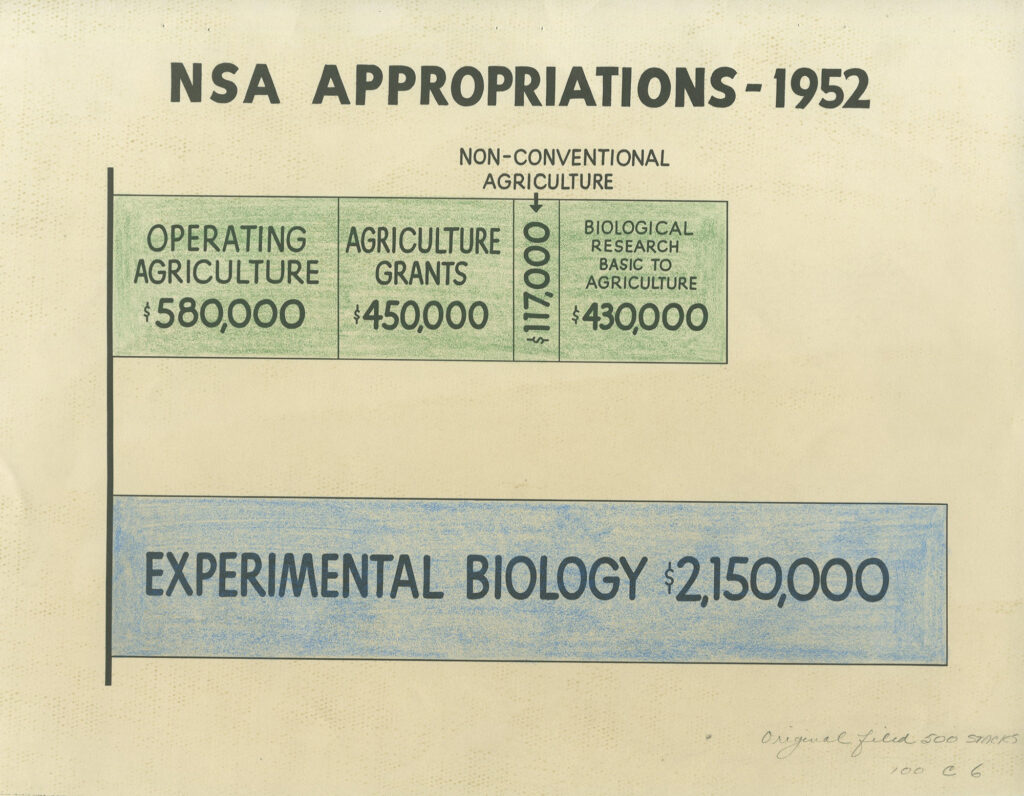

The rapid pace of progress in the field, which sped up even further during World War II, invited government and industry to begin to fund molecular biology research on a larger scale by the 1950s. Weaver himself was the architect of the Foundation’s exit plan from experimental biology, urging the Foundation to turn its attention to the more applied work of agriculture, which could mobilize molecular biology’s contributions to plant breeding in direct service to ending hunger. In fact, the rationale for housing the operating program in agriculture within the Division of Natural Sciences ass opposed to health or social sciences, was that it utilized biological research.

The Rockefeller Foundation set the stage in the 1930s for molecular biology to occupy a significant space within the scientific community by the late twentieth century. In the 1980s and 1990s, with other agencies largely covering the food distribution programs the RF pioneered in the 1960s, the Foundation was able to return to funding bench science through its International Program in Rice Biotechnology.

Rice Biotechnology: A Later Chapter in a Longstanding Legacy

In the early 1980s, the Rockefeller Foundation undertook an ambitious rice program that in many ways represented a return to its historical roots in molecular biology. RF-supported basic research had enabled the emergence of molecular biology as a field in the 1930s and 1940s. But as industry and government began taking funding for such research to a larger scale, the Foundation shifted its support to global agriculture, work that sparked the “Green Revolution” in the 1950s and 1960s.

By the 1980s, RF-initiated programs in food production and distribution had become largely self-sufficient or replicated by a host of other agencies. Meanwhile, researchers in molecular biology were on the verge of significant breakthroughs in genomic mapping, and the Foundation now sought to capitalize on technologies that might help solve more intricate problems of nutritional content in food, not simply the provision of calories. The International Program in Rice Biotechnology (IPRB), launched in 1984, reinvigorated the Foundation’s support of biological research.

Agriculture’s Next Steps

In 1981, the Foundation undertook an extensive evaluation of its agricultural commitments. The external review team concluded that the time was right for the Foundation to return to supporting research and recommended that it pursue the potential of emerging discoveries in molecular biology in hopes of applying them to plant breeding.

In 1984, the Trustees approved a comprehensive program on rice projected to last 10 to 15 years. Rice was selected because it served as a dietary staple for a large part of the world. But rice, in the world of plant biology, was far less understood than other staple crops. At the time, no DNA markers or maps had been identified or created. There was no evidence that rice could be transformed with novel genes.

The Return to Research

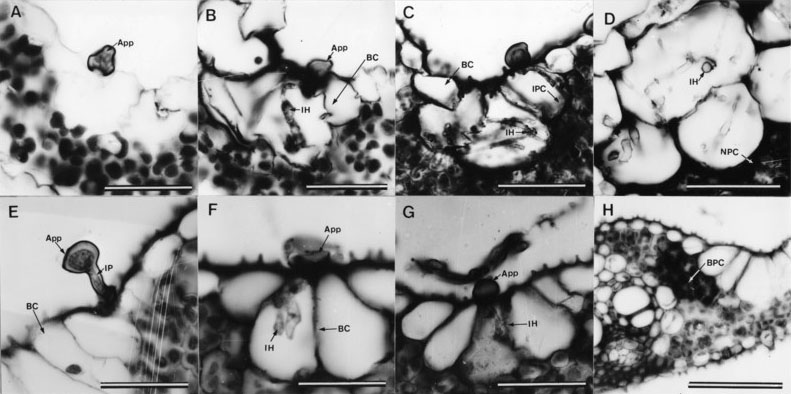

The Foundation stimulated rice research through strategically placed grants, much as it had for molecular biology when it had been a new field, in some cases convincing reluctant but especially well-qualified laboratories to take on new research. Major grants were made to institutions including Cornell University, Stanford University, Purdue University, the State University of Ghent in Belgium and the State University of Leiden in the Netherlands. By 1988, a DNA map was achieved, and by 1990 the first experimental genetic transformation had been accomplished.

Encouraged by its quick success, the IPRB turned to the ambitious goal of transferring these new technologies to rice researchers worldwide, especially in rice-consuming countries. By the 1990s, rice became the model plant for cereal genomic research, the “mother of all cereals,” and full-scale genome-sequencing projects were undertaken in Japan and the United States.

Building an International Infrastructure

Ultimately, the Rockefeller Foundation sought to enable farmers to produce greater supplies of more nutritious food while minimizing environmental damage. Funding targeted the creation of sufficient biotechnology capacity in rice-dependent countries, many of which lacked robust infrastructure. Research projects tested how the tools of biotechnology could be applied to varieties of tropical rice. The Foundation also needed to understand the consequences of agricultural change in Asia in order to foster the agronomic support necessary to to achieve the region’s adoption of new technologies.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s strategic approach to rice biotechnology was informed by decades of experience in agricultural development. Its central strategy encouraged international collaboration and focused on using research as an opportunity for training. Through graduate, dissertation, and post-doctoral fellowships, the RF built a network of highly trained experts who continued to share information and conduct joint research even after their education was completed. It further promoted knowledge exchange through sponsoring international summits and conferences.

Rockefeller Foundation financial support, coupled with this expanding cohort of experienced researchers, strengthened a core group of institutional centers. The Foundation placed field staff in Asian countries to build technical and human resource capacity so that new techniques in plant breeding, invented in predominantly Western institutions, could be applied on the ground in rice-consuming nations.

The International Program in Rice Biotechnology supported a new academic journal as well, the Rice Biotechnology Quarterly, and the publication and circulation of theses, reprints, books, and patents. Finally, the program initiated relationships with national agencies that might eventually assume responsibility for the funding and management of rice research.

Legacy

Over 700 scientists from approximately 30 countries participated in the International Program in Rice Biotechnology by the time it concluded in 2000. The identification of genes that provided immunity from blight enabled the engineering of blight-resistant rice. “Golden rice,” a genetically modified hybrid that introduced Vitamin A into the calorie-filled but otherwise nutrient-lacking grain offered better nutrition to millions.

One of the most lasting effects of the program was that rice went from being a marginal interest in plant molecular biology to its very cornerstone, all in the space of only seventeen years. In 1995, IPRB research predicted that rice would prove to be the “model cereal” for genomic research. All major cereal crop genomes can be represented by the 19 segments found in the rice genome. Since that discovery, rice-centered research has accelerated, and the IPRB work has continued through the Asian Rice Biotechnology Network, sponsored by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), as well as national programs in China, Thailand, India and the Philippines.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “California Institute of Technology,” 1929-1939. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, California, Series 205, California – Natural Sciences and Agriculture, Subseries 205.D, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “California Institute of Technology – Biology and Chemistry,” 1932-1934 June. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, California, Series 205, California – Natural Sciences and Agriculture, Subseries 205.D, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro 1 – Pro – 5a,” 1916-1933. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 1, Natural Sciences and Agriculture, Series 915, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro 6 – Pro – 9,” 1916-1933. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 1, Natural Sciences and Agriculture, Series 915, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro 10 – Pro – 16,” 1916-1933. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 1, Natural Sciences and Agriculture, Series 915, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro 25 – Pro – 29a,” 1948-1953. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 1, Natural Sciences and Agriculture, Series 915, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Food Policy – Reports – Pro FP-6a – Food and Agricultural Policy Documents 80-89,” 1981-1982. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy, Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.