The Rockefeller Foundation and the Green Revolution

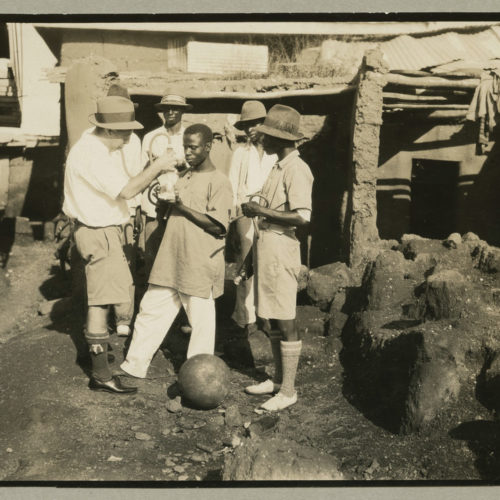

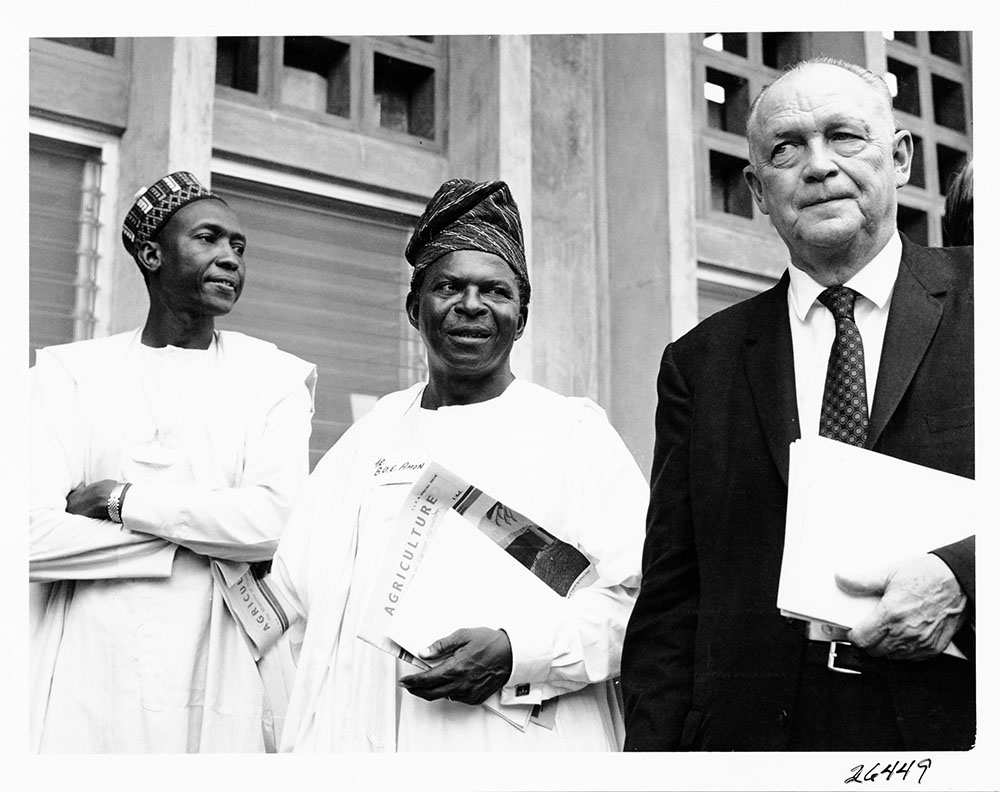

In October 1963, Richard Bradfield, a leading agronomist for the Rockefeller Foundation, visited Nigeria to explore the possibility of opening the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (IITA) at the University of Ibadan.

At that point in time, the Foundation had already helped countries across Asia and Latin America grow more food, and had launched research and training programs that produced high-yielding varieties of maize, wheat, and rice in Mexico, Colombia, the Philippines, and elsewhere. Collectively, these programs were central to the RF’s international agriculture program, Toward the Conquest of Hunger, which aimed to increase the developing world’s food supply. As a result, many recognized the RF as the creator of what we today call the Green Revolution.

Bringing the Green Revolution to Africa.

Now, Bradfield hoped to bring the Green Revolution to Africa. But the task would not be easy. Nigeria had large swaths of poor soil and uncultivated land, and a large base of subsistence farmers who grew non-staple crops using shifting cultivation.

Nevertheless, Bradfield returned optimistic. The country’s climactic variations mirrored those of the wider tropics and it had a strong potential home for IITA in the University of Ibadan, which maintained a College of Agriculture, resided near other agricultural institutions, and had already received over $1 million in RF grants for various purposes since the 1950s.Richard Bradfield, “Summary of Observations of Nigerian Agriculture and Agricultural Institutions,” October 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center; Diary Entry of John J. McKelvey, Jr., November 6, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center; for other grants made to the University of Ibadan, see Rockefeller Foundation Annual Reports, 1959, 1961, 1963 (New York: Rockefeller Foundation).

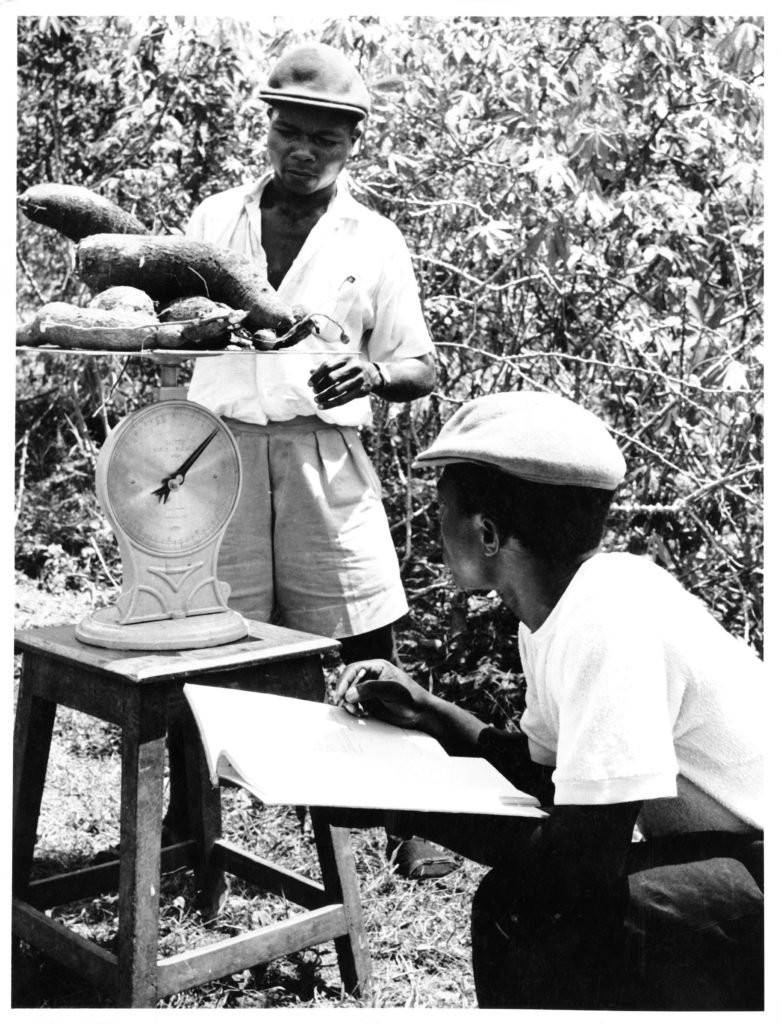

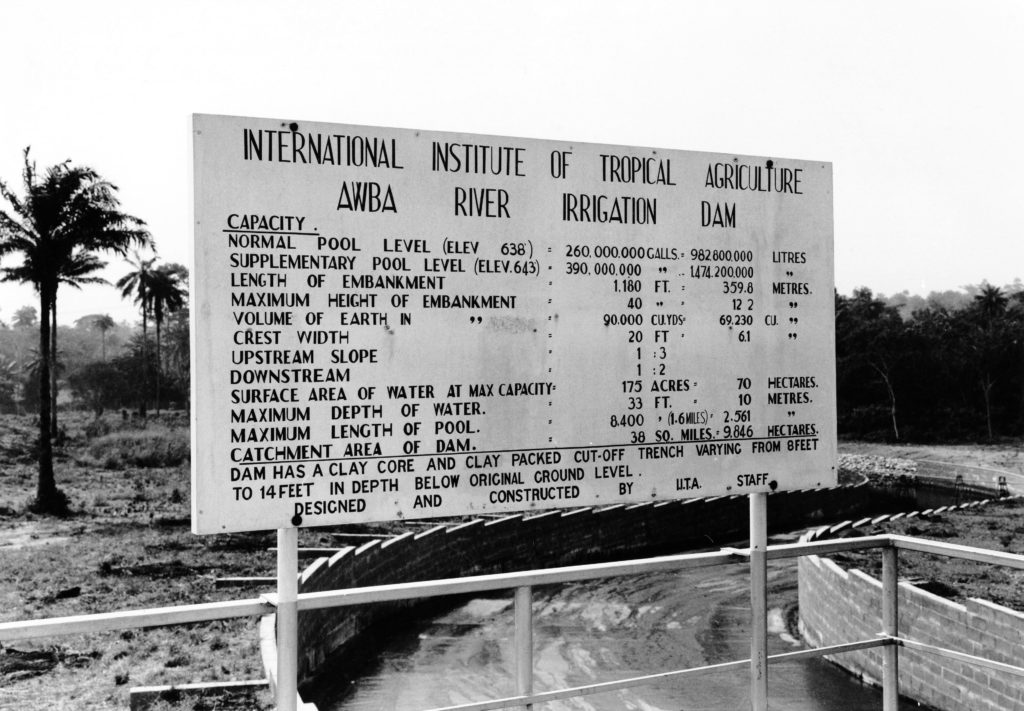

Buoyed by these factors, the RF joined the Ford Foundation, which had already been working in Nigeria, to establish the proposed new institute. In the coming years, IITA would help the African tropics improve maize and rice output, develop new breeds of non-staple crops like grain legumes and root crops, and revamp entire crop management systems. By 1980, the Institute was recognized “as a center of excellence in tropical agricultural research in Africa.”William K. Gamble, “Evolution of the Program of the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture,” Sterling Wortman papers, Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

But IITA almost never came to be.

Just as the RF and Ford put into motion their plans to build IITA, something entirely unpredictable occurred. A disputed federal election, featuring allegations of voter fraud and a massive boycott, triggered widespread social unrest in Nigeria. Suddenly, the Institute found itself trapped in a vortex of unexpected geographic and ethnic conflict. An air of distrust and anxiety enveloped the University of Ibadan and, after two military coups, a civil war erupted. By 1967, Nigeria had been split in two.

These events raised several questions about philanthropic practice: when should foundations exit from programs that may not pan out? How should they navigate volatile conditions in foreign countries? Can foundations remain nonpartisan in the face of pervasive political conflict?

Civil War in Nigeria

In December 1964, The New York Times described the start of what it termed the “gravest crisis” in Nigeria’s recent history. The crisis centered on the first federal election in Nigeria since gaining its independence from the United Kingdom in 1960. More than 300 parliamentary seats were at stake. The contest exacerbated geographic, ethnic, and religious tensions in the country, and provoked a degree of social and political discord that threatened to sabotage the RF and Ford’s plans.Lloyd Garrison, “Nigeria in Crisis Over Vote Plans,” The New York Times, December 29, 1964.

…It will be some time before it will be appropriate for us to think of talking again with the government of Nigeria about the proposed Tropical Institute.George Harrar to Joseph E. Black, January 8, 1965, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The 1964 election featured three main electoral blocs that jostled for power: the Hausa peoples, a northern faction of predominantly ethnic Muslims; the mostly Christian Igbo peoples in the southeast; and the Yoruba peoples in the southwest. Commentators predicted that the northern Hausas would win a majority of the parliamentary seats that were up for grabs.

But large numbers of Yorubas and Igbos boycotted the election, claiming their candidates had been illegally imprisoned and banned from entering the race. When the election proceeded anyway, the country’s eastern Igbo bloc called for the president, an Igbo electoral ally, to divide the nation’s assets and peacefully dissolve the country.Lloyd Garrison, “Nigeria Appears Near a Breakup,” The New York Times, December 30, 1964; “Nigeria’s Election,” The New York Times, December 31, 1964; Lloyd Garrison, “Key Nigeria Party Urges a Breakup,” The New York Times, December 31, 1964; Lloyd Garrison, “Nigeria’s Crisis of Democracy,” The New York Times, January 3, 1965.

The RF and Ford monitored these developments closely, and RF President George Harrar expressed strong reservations about opening IITA in Nigeria. “It will be some time,” he wrote, “before it will be appropriate for us to think of talking again with the government of Nigeria about the proposed institute.”George Harrar to Joseph E. Black, January 8, 1965, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Tensions Escalate Further

In January 1966, disgruntled Igbo army officers staged a coup that killed four high-ranking northern officials, including the Nigerian Prime Minister. In response, northern soldiers staged a counter-coup that killed thousands of Igbos. As a result of this violence, Igbo leaders seceded from the country in May 1967, declaring the Republic of Biafra (territory in eastern Nigeria) a new independent state.

A bloody civil war followed, lasting over two years and intensifying the country’s social and political strife. While federal authorities put down the rebellion in 1970 and reincorporated the eastern Biafran state into the country, these events unfolded just as the RF and Ford completed negotiations with Nigerian authorities to open IITA.“Nigeria: Civil War,” Mass Atrocity Endings, accessed April 12, 2019; “How First Coup Still Haunts Nigeria Fifty Years Later,” BBC News, accessed April 12, 2019.

Growing Uncertainty

Throughout the conflict, RF and Ford officials received real-time reports of on the ground developments in Nigeria. Both foundations had to improvise and develop a flexible strategy that would allow them to continue or abandon the project as necessary.

Roughly eleven months after the federal election, David Heaps, Ford’s representative in Nigeria, described alarming censorship and curfew laws installed throughout the western part of the country, where the University of Ibadan is located. He expressed his concern over Kenneth Dike, an Igbo historian who served as Ibadan’s Vice Chancellor.

The recent electoral turmoil, Heaps felt, had led Dike to enter a “highly nervous state” and to encourage “rumors, suspicions, and fears” that threatened to divide the campus. Senior administrators had also entered a condition of “frantic excitement, verging almost on panic.” Given these circumstances, Heaps questioned whether Ibadan was the right location for IITA.

But Heaps also felt it was too late to leave. There was still a good chance that any of the factions that became Nigeria’s ruling party would view IITA as a means to solidify Nigeria’s international standing (and thereby helping legitimize that faction’s power).David Heaps to F.F. Hill and George Harrar, “International Institute of Tropical Agriculture and the Nigerian Political Situation,” November 13, 1965, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Even as tensions mounted, foundation officials remained optimistic.

After the January 1966 Igbo coup, Ford and RF characterized conditions in the country as peaceful and noted the new government had continued to secure the land on which IITA would operate.

After another uprising –a counter-coup in July 1966 –-one Ford administrator in Nigeria acknowledged the situation as dangerous and uncertain, but predicted the Nigerian people would “probably realize the complete folly of a complete division of the country into regions.”J. Robert Mitchell to Will M. Myers, August 19, 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Shortly thereafter, Sterling Wortman, Director of RF’s Agricultural Sciences Division, Will M. Myers, IITA’s first director, and Frosty Hill, Ford Vice President, recommended the foundations delay some construction on the IITA site, and concentrate instead on developing its future research program.

“Despite two upheavals,” Myers reminded George Harrar in a letter outlining this suggested course of action, “the government of Nigeria has moved forward steadily with Nigeria’s responsibilities to the IITA project.”Will M. Myers to George Harrar, September 9, 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Unconvinced, Harrar asked Myers to speak with RF staff families about their experiences in Nigeria. Myers then reaffirmed what others had said before: secession was unlikely and, despite rumors to the contrary, the university had experienced little actual unrest. The RF families Myers spoke with felt secure and were, he lightly noted, “as safe here as they are in New York.”

More importantly, Myers added, the RF had already invested significant resources in the University of Ibadan to establish IITA:

This is not the time to abandon it, if for no other reason than to protect our investment…I believe the stakes are high enough to warrant the risks.William Myers to George Harrar, November 4, 1966, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture is Born

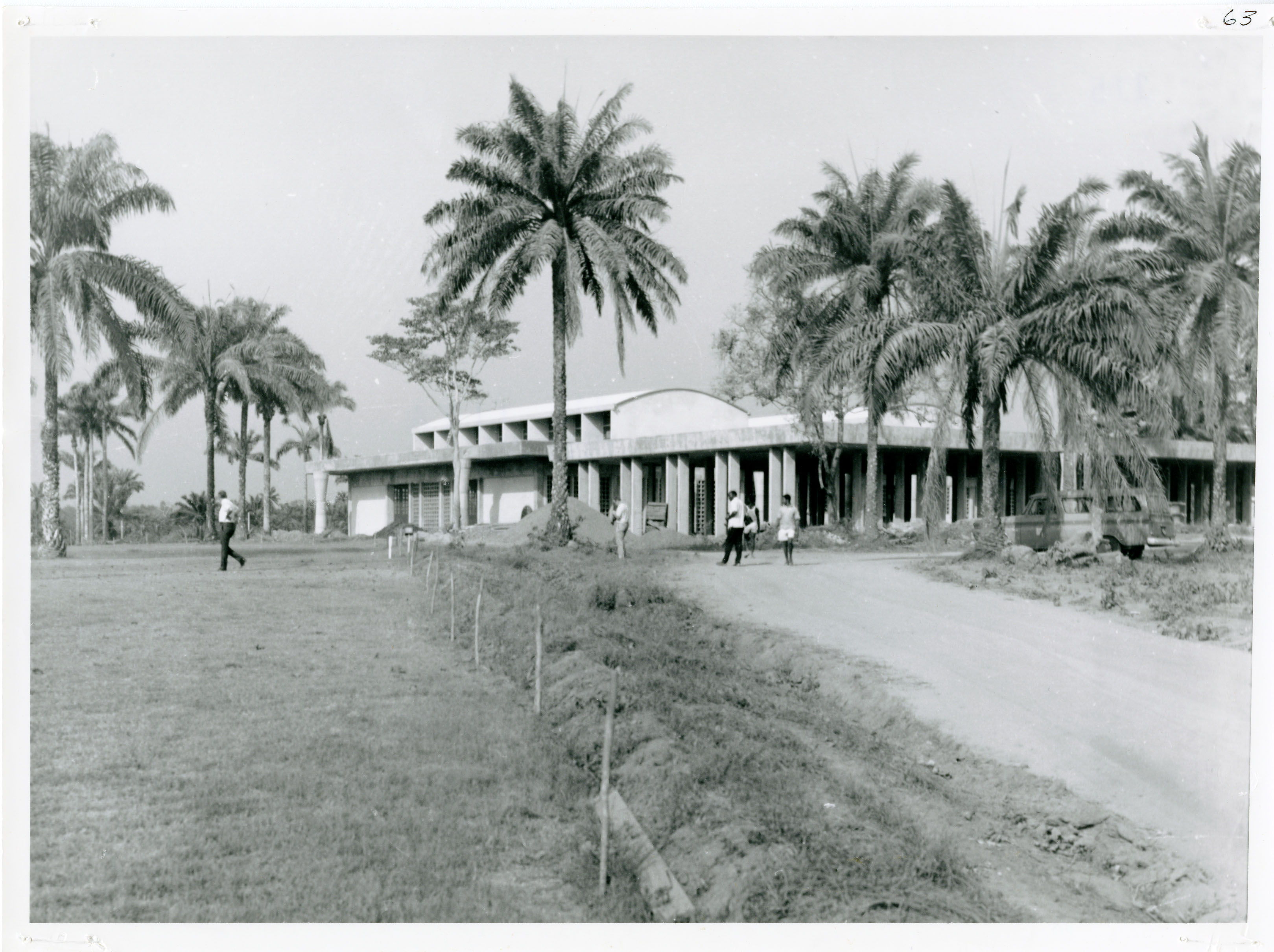

in the end, the arguments to proceed held the day. IITA was formally established in July 1967, less than two months after Biafra seceded from Nigeria. One year later, in the midst of civil war, the Institute’s Board of Trustees held its first meeting. Ford and RF representatives proposed supporting IITA for at least fourteen years, with Ford supplying significant funds for IITA’s initial construction and equipment costs and the foundations splitting the operational costs.

From a distance, the Institute appeared immune to the unrest in eastern Nigeria. As IITA continued to expand its facilities in 1969, a report claimed that “there has been no evidence that the Nigerian civil war will adversely affect in any way the development of IITA or the conduct of its activities.”“The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture,” 1969, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.3, Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Lessons Learned

But underneath the surface, a series of maneuvers by the RF and Ford helped guarantee this apparent stability. The foundations insulated IITA from Nigeria’s escalating conflict by adopting a universally-appealing, non-political mission for the Institute – addressing chronic food shortages in tropical Africa. They deftly navigated domestic unrest in a foreign nation through constant monitoring and review through a network of on the ground contacts. Rather than taking sides in a brewing civil war or abandoning the project entirely, the foundations carefully followed conditions at the University of Ibadan and adapted, when necessary, to the country’s fluid political situation by pausing certain aspects of construction and planning. This patient and neutral approach, coupled with the Institute’s inherent appeal, helped shield IITA from local tensions.

The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture has now been a major player in international agriculture for some time. It operates in thirty-five African countries with a focus on developing nutritious and high-yield crops for small farmers. The stakes, as Will M. Myers noted over fifty years ago, seem to have indeed warranted the risks.

Related

Ping-Pong Diplomacy: NGOs and International Relations

When a friendly interaction unexpectedly emerged between American and Chinese table tennis players, one nonprofit seized the opportunity to support broader cultural diplomacy.