In the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records there is a folder labeled “People’s Institute – New York City – Community Work.” In it are photographs of Eastern European women demonstrating and exhibiting their needlework skills in New York City sometime between 1919 and 1929. These women were most likely members of the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild, an organization which operated under the auspices of the People’s Institute, a Progressive Era reform organization.

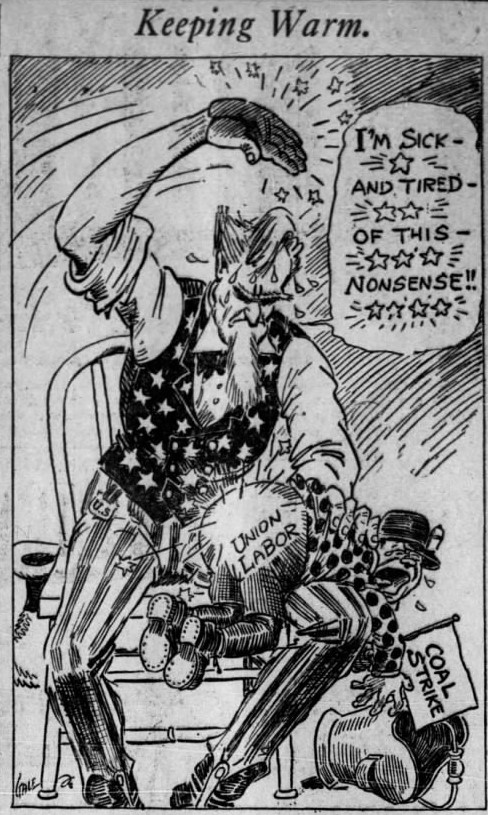

The women in these photos came to the US fleeing political unrest and sat at the center of several powerful forces of the Progressive Era (1890-1920): increased immigration, demands for women’s rights, socialist politics in the US, the first Red Scare of 1919, anarchist violence, and brutal conflicts between labor and capital.

The People’s Institute and Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild records, held at both the RAC and the New York Public Library, reveal how reveal how the People’s Institute—while publicly supporting workers’ rights and union labor—shrewdly crafted their requests for funding to the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial using explicit, anti-radical language during a time of anti-socialist anxiety.

In these funding appeals, the People’s Institute frequently described its work as “the right kind of Americanization” throughout their appeals. Its requests were going to one of the Rockefeller philanthropies. The Rockefellers were widely known as anti-radical, particularly on issues of labor, given the family’s recent dust-up in the Ludlow Massacre at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company.

The Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild offers a lens through which to examine the entanglement of Progressive Era reform, immigration, labor, and early twentieth-century philanthropy. This story traces how the People’s Institute translated its social and cultural work into a language legible—and reassuring—to elite funders during a period of intense anti-radical anxiety.

Although the People’s Institute succeeded in obtaining a modest amount of Rockefeller funding over a remarkably long period—nearly three decades—it was never able to convince the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial to increase its support to a level that would have enabled the Institute to expand its reach. What was the project of Americanization, and how was the People’s Institute’s approach compelling enough to receive consistent Rockefeller funding but not to obtain enough funding to grow?

Immigrant Women in Progressive Era New York City

Foreign born women are in danger of losing their traditional skill, and at the same time of failing to make their individual contribution to American life.

The People’s Institute Annual Report 1920-1921 People’s Institute – Reports, 1917-1949; Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; Appropriations, Series 3; Appropriations – Social Welfare, Subseries 3_07; Rockefeller Archive Center https://dimes.rockarch.org/objects/RwPKWyoSdfoNqGtjQbzaZj

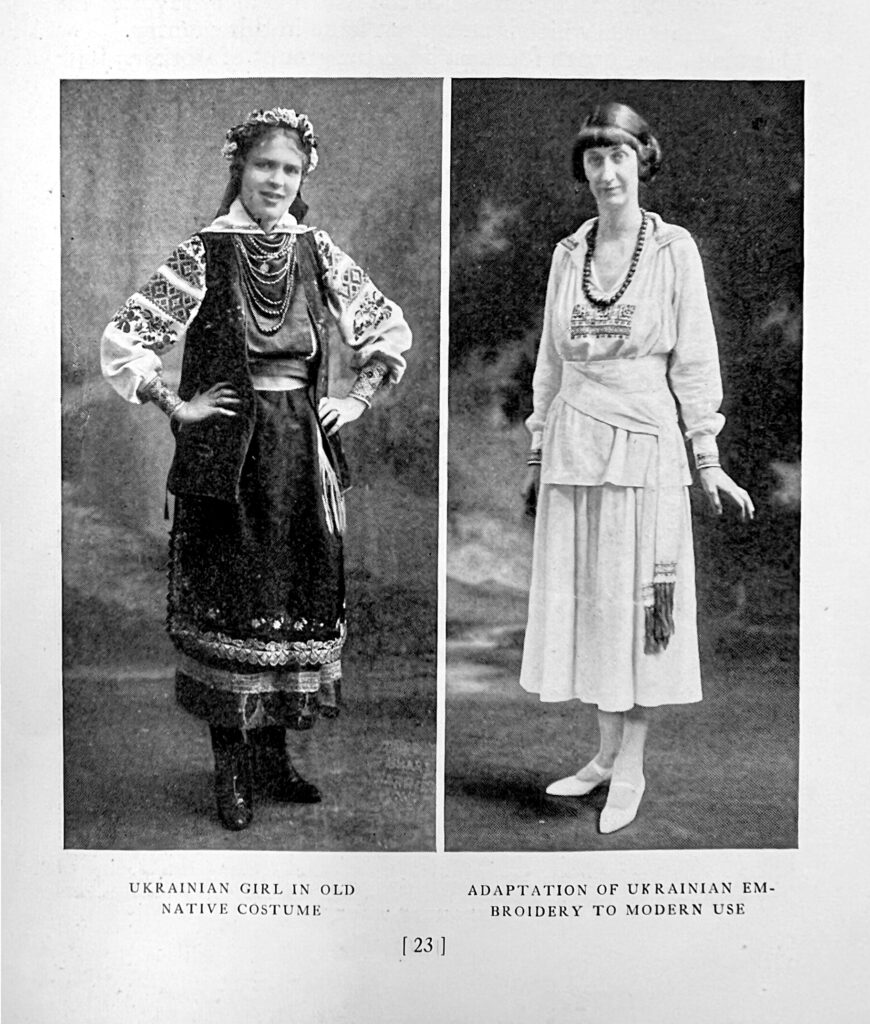

PhotographsPhotographs – People’s Institute, New York City – Community Work, 1919-1924; Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; Appropriations, Series 3; Appropriations – Social Welfare, Subseries 3_07; Rockefeller Archive Center; https://dimes.rockarch.org/objects/d4vo8tgxkBCbPAJh6S8DVt from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (LSRM) records depict eastern European needleworkers demonstrating and exhibiting their skills in New York City sometime between 1919 and 1929. They are assumed to have been members of the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild, an organization which operated under the auspices of the People’s Institute.

The needleworkers encountered an urban environment undergoing rapid change. The early 20th century was an era of economic growth, demographic shifts, and political tension between capital and labor. The United States was receiving an influx of immigrants from southern and Eastern Europe. Newcomers like these craftswomen brought with them cultures, cuisines, languages, and religious practices to which most Americans were unaccustomed.

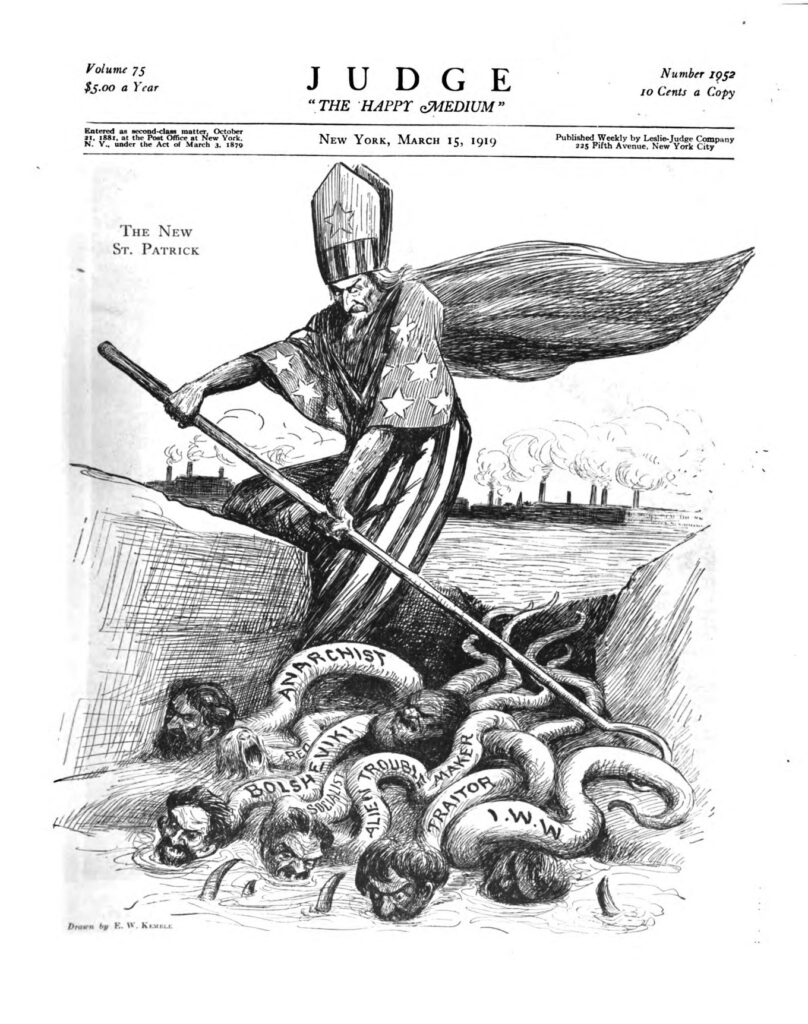

Immigration, Labor, and Radical Activism

As has so often been the case throughout American history, this influx of immigrants in the 1910s and 1920s provoked uneasiness. Americans’ suspicions of Eastern European “outsiders” were exacerbated by Vladimir Lenin’s 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Fears of far-left radicals and communist ideas infiltrating US labor organizations and the women’s suffrage movement ran rampant. Anti-immigration and anti-communist sentiments induced the nation’s first Red Scare of 1919-1920.

Fears of violence were not unfounded. The previous decades had seen anarchist bombings and the 1901 assassination of President William McKinley by Leon Czolgosz. Activists such as the Russian-born radical anarchist Emma Goldman advocated for revolution via political violence to end exploitative working conditions and the government’s brutal strike-breaking tactics. Powerful government officials and politicians conflated labor organizers with violent anarchists. They portrayed them as manipulative agitators preying on gullible foreigners.

Americanization before Radicalization

Consequently, these conditions influenced the ways in which Progressive Era reformers appealed to potential funders. The wealthy industrialists and their allies feared political violence from the left. Americans had grappled with the influx of foreigners in myriad ways, most often by engaging in debates about what it meant to be an American. This led to an “Americanization” project aiming to cement immigrants’ loyalty to the United States and to so-called “American values.”

The People’s Institute, supported by the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, was one organization among many that played a role. While People’s Institute leaders and staff portrayed themselves as progressive and inclusive, further research reveals the more conservative underpinnings of their programming. It also highlights the ways in which they endeavored to mitigate the spread of radicalization and potential violence, even in an endeavor as seemingly benign as the needlework crafts.

Progressive Era Reformers Tackle the Challenges of Urbanization

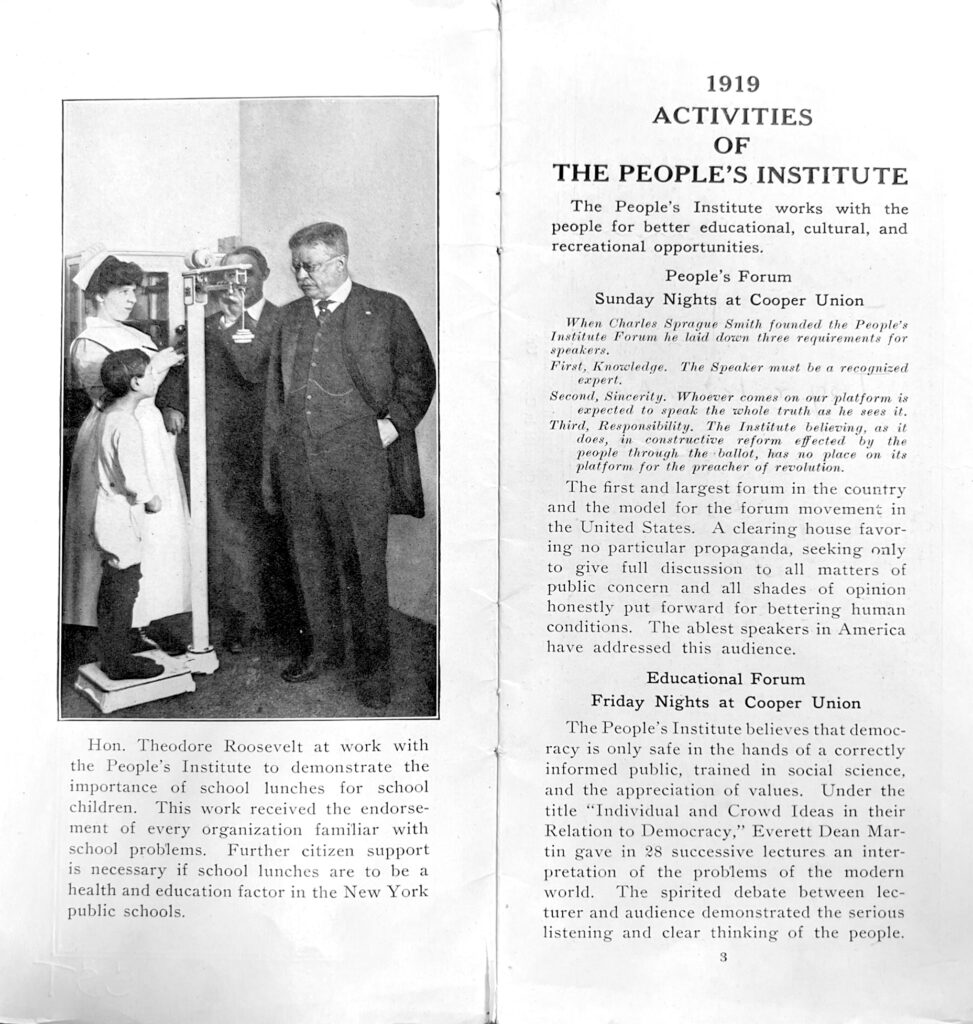

The People’s Institute was a Progressive Era organization founded in New York City by Columbia University Professor Charles Sprague Smith in 1897. Smith’s mission was to provide the space and resources to teach civics and social philosophy to workers and recent immigrants in New York City.

Broadly considered, there is no greater educational need within a democracy than training for participation in public life.

Charles Sprague Smith, “Working with the People” 1904.

Progressive Era reformers—predominantly white and from the middle class—were keen to address the challenges that arose during this era of rapid industrialization and urbanization. Such issues included housing, hygiene, and education. Reformers felt that too much power had concentrated in the hands of corrupt political machines (see: Tammany Hall) and ever-expanding corporate monopolies. They founded several organizations to aid in the Americanization of immigrant populations, particularly in major cities like New York, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Chicago.

This pursuit, they felt, was both benevolent and strategic. On the one hand, providing education in English, civics, social philosophy, and homemaking would integrate and cultivate economically productive citizens. But also, an emphasis on “American values” would, in theory, overcome any loyalty immigrants may have retained to their home countries – especially coming out of the region affected by the Russian Revolution. Most importantly, it would eliminate any radical political ideologies that might threaten American democracy and capitalism.

Progressivism wanted to get the control of the government back into the hands of the people—the right people, that is—those who understood American values, i.e., the reformers’ values.

Carlson, R. A. (1970). Americanization as an Early Twentieth-Century Adult Education Movement. History of Education Quarterly, 10(4), 440–464.

The People’s Institute – Cooperation vs Revolution

Charles Sprague Smith began the People’s Institute with a belief in robust, diverse democracy. In its 1918 Yearbook, Director John Collier said of Smith:

[No principle] represented a more intense conviction than the principle of the right of groups representing special interests and sentiments to work out their destiny in the American commonwealth.

The People’s Institute Yearbook, 1918-1919

The People’s Institute emphasized cultural and social education to integrate foreigners into American life. This was achieved through a successful, long-running lecture series called the Cooper Union Forum, a public concert program, and the establishment of multiple community centers. The Institute also supported vocational activities such as the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild. The People’s Institute operated without an endowment and relied solely on membership subscriptions and philanthropic funding.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. had supported the People’s Institute with annual gifts since 1901, first independently and then via the Rockefeller Foundation after its establishment in 1913. The Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial took over many of his donations for social welfare interests after 1919 as the RF’s focus was on funding public health and medical education rather than social issues.

The People’s Institute maintained that its philosophy towards Americanization was based in communication between different interest groups to encourage cooperation and understanding. And yet, upon closer inspection a latent paternalism comes into focus, for example, with assumptions about immigrants’ judgment:

We try to help the people reflect and examine critically, rather than to fan the flames of fanaticism.

The foreign born […] do not lack intelligence, many of them being widely read. But frequently they lack judgment. By hearing their pet philosophies subjected to intelligent criticism, many of them get their only experience of tolerance.

We have always maintained that in a country like ours, it is in the hands of the people to remedy social and political evils through the ballot, not through advocating revolution.

Henry de Forest Baldwin, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the People’s Institute, quoted in The New York Times, November 5th 1922.

Women and Citizenship in the 1910s

The formation of the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild also came at a rapidly changing era for American women. The women’s suffrage movement was about to achieve its ultimate goal: a constitutional amendment granting the vote to American women (although in practice, predominantly white women).

At this time, however, most of a woman’s legal identity—including her citizenship—was directly tied to that of her father or husband due to a doctrine known as coverture. If an American woman married a foreign-born man, it was considered her consent to relinquish her own American citizenship. It would not be until 1922’s passage of the Cable Act that women would have authority to retain their citizenship status regardless of marriage, with some exceptions.

These circumstances left immigrant women in a tenuous position and with far fewer legal protections and less political agency than their male counterparts. With limited access to naturalization or citizenship—save for marrying an American man—participation in the American economy was a key method for women to support themselves and their families. And it created an opening for Progressive reformers to “Americanize” them.

Around 1920, the People’s Institute began a concentrated campaign to raise funds to support the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild. They sent several appeals to the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial for additional funds which were ultimately declined. This correspondence, however, highlights how organizations were confident that Americanization would be a compelling argument for funders. In one appeal, Guild Director Cora McDowell directly linked the work of the Guild with the Americanization of immigrants:

This is not a part of the regular work of the People’s Institute, but an unusual service that we feel is the right kind of Americanization.

Appeal from Miss Cora McDowell to W.S. Richardson, June 15th, 1920. People’s Institute, 1919-1920; Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; Appropriations, Series 3; Appropriations – Social Welfare, Subseries 3_07; Rockefeller Archive Center; https://dimes.rockarch.org/objects/kQFL5ZTRwLx8cvHGRWniuG

The Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild

In the fall of 1919, Father Pidhoresky, of the Ukrainian Settlement at 217 East 6th Street, asked Miss Cora McDowell, who was in charge of the Institute’s work in that section, to help him show to his people the value, both to themselves and to America, of their own artistic inheritance.

The People’s Institute Annual Report, 1920-1921. People’s Institute – Reports, 1917-1949; Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; Appropriations, Series 3; Appropriations – Social Welfare, Subseries 3_07; Rockefeller Archive Center; https://dimes.rockarch.org/objects/RwPKWyoSdfoNqGtjQbzaZj

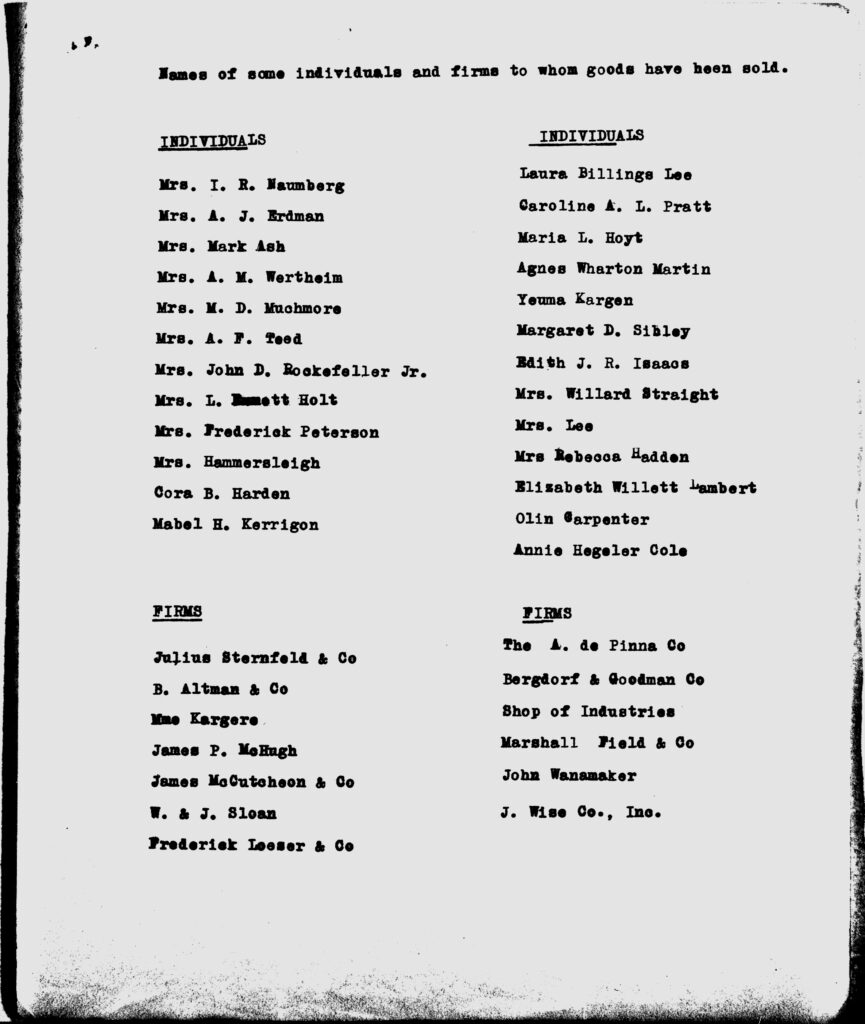

As is often the case today, the resounding argument from Progressive Era advocates in favor of immigration to the US was potential economic productivity. Additionally, the Arts and Crafts movement—begun in mid-19th century England as a reaction to the second industrial revolution—had made the journey across the Atlantic and was taking hold among American tastemakers. The backlash against the rise of mechanization in the textile industry had created a demand for traditional hand needlework for everything from clothing to home decor. Retail giants like Wanamaker’s, Lord & Taylor, Bergdorf Goodman, and Abercrombie & Fitch all made multiple orders from the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild to sell in their department stores.

The Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild’s format was successful enough to be expanded into a larger organization called the Guild of Needle and Bobbin Crafts. This included more nationality-based needlework guilds such as the Bohemian Arts and Crafts of Lenox Hill Settlement and the Italian Needlework Guild of Hamilton House. The Ukrainian Guild organized several exhibitions—such as the ones seen in these images—at their permanent Sales Centre at 70 Fifth Avenue in New York, at halls, or even in the homes of prominent society ladies.

The People’s Institute’s continued appeals to the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial emphasized the value of the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild would have as a positive contribution to the American economy.

Aside from the important commercial fact that there is real demand from the New York industries for the individual quality of these women’s work, the Institute believes that there is a great inspiration and a genuine Americanization factor for whole groups of foreign people in our appreciation of what they have to give to the Art and Industry of America.

Appeal from the People’s Institute to LSRM, January 12th, 1920

People’s Institute, 1919-1920; Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; Appropriations, Series 3; Appropriations – Social Welfare, Subseries 3_07; Rockefeller Archive Center; https://dimes.rockarch.org/objects/kQFL5ZTRwLx8cvHGRWniuG

It is revealing to examine how the People’s Institute portrayed the integration of immigrants not as a project of assimilation by giving up cultural practices, but instead as a means of making new contributions to American culture itself. Progressive organizations were diverse in their methodologies of Americanization. Several groups believed immigrants were Americanized only after doing away with the traditional food and cultural practices of their homelands. Yet the People’s Institute asked: how could the traditional needlework of these women enhance and diversify American arts and craft?

By giving these people an opportunity to work with their hands, and so to offer to their new land something beautiful and dear, America not only gains valuable citizens, but also enriches her own artistic and industrial life.

People’s Institute’s Annual Report for 1920-1921

“The Right Kind of Americanization”

And yet, it is equally significant to highlight how the work of the Ukrainian needleworkers was portrayed within the context of the larger conversation regarding labor and socialist politics. The previous decade had seen the rise of young immigrant women in the workforce. Tragedies such as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire increased the membership of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) which organized several successful strikes. These strikes were often met with violence.

In what appears to be an internal report on the Ukrainian needlework industry and the work of the Guild, a People’s Institute staff member emphasized the familial status of the needleworkers:

It is interesting to note that all of these women are married and a majority of them are mothers.

[The Ukrainian Needlework Industry was] Established with a twofold purpose, to make available to the public the beautiful hand-work from the Ukraine, and to give employment of a congenial kind to married women not as a vocation but as an avocation, the results are most satisfactory. The women take their work home where they embroider during leisure hours.

New York Public Library Special Collections, the People’s Institute Records Series VII. Community Work 1899 – 1926.

The Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild, Reports and Related Materials.

https://archives.nypl.org/mss/2380#c173786

Put in today’s terms, the work of the women in the Guild was advertised as Americanization via a domestic side-hustle. The goal was not to have immigrant women enter the full-time workforce. These women, the report implies, would not be the ones joining picket lines and striking for better working conditions.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s Support for Working Women

Notably, according to the LSRM records, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller advocated for the support of the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild. A strong supporter of the arts (she co-founded MoMA), records show she had even been a customer:

(See also: department store giants like Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia; Marshall Field’s in Chicago; and Bergdorf Goodman in New York City.)

Abby had a history of supporting organizations that improved the lives of working women. In the correspondence between LSRM executive W.S. Richardson and Cora McDowell, McDowell mentions:

In my talk with Mrs. Rockefeller, she was particularly interested, not only in the artistic value of the work, but because we are reaching women who are difficult of approach and are helping them to help themselves.

Appeal from Miss Cora McDowell to W. S. Richardson, June 15th, 1920. People’s Institute, 1919-1920; Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; Appropriations, Series 3; Appropriations – Social Welfare, Subseries 3_07; Rockefeller Archive Center; https://dimes.rockarch.org/objects/kQFL5ZTRwLx8cvHGRWniuG

The People’s Institute Appeals to the Rockefellers’ Anti-union Sentiments

The People’s Institute maintained a policy of cooperating with labor unions, which on the surface may seem opposed to the antagonistic relationship members of the Rockefeller family had had with labor.

For the previous decade, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. had been grappling with the fallout of the violent anti-union, strike-breaking confrontation at the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, also known as the Ludlow Massacre in April of 1914.Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Ron Chernow, 1998.His father, John D. Rockefeller, Sr., had long maintained a hostile and contemptuous view towards labor organizing. Senior’s refusal to cooperate with the union—and Junior’s compliance—boiled over into violence which led to the deaths of several workers and their families.

[John D. Rockefeller, Sr.] could never see unions as anything other than frauds perpetrated by feckless workers. “It is all beautiful at the beginning; they give their organization a fine name and declare a set of righteous principles,” he said. “But soon the real object of their organizing shows itself–to do as little as possible for the greatest possible pay.”

At Pocantico, he did now allow employees to take Labor Day as a vacation and fired one group that tried to unionize.

Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., 1998, p574.

The violence in Colorado was a public relations nightmare for the Rockefellers and, as the controlling shareholder, Junior was quickly cast as the villain. The fallout led to an ideological split between father and son. (While Senior maintained his derisive attitude towards unions, Junior would go on to support building the field of Industrial Relations, with the hopes that management and labor could work together and come to an understanding that benefited both parties.)

Given this context, it is unsurprising that in their 1921 appeal to the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial for continued support, the People’s Institute’s language became more explicit in the kind of ideologies and activities they were trying to prevent with their programming.

The work of the [Cooper Union] Forum during the past year has been a campaign against cheap propaganda, such as is pactised [sic] on the people on all sides by unscrupulous leaders.

There is no doubt that the Cooper Union Forum has done very much during the past year to open the eyes of restless groups who do not entirely understand American ideals to the dangers of revolutionary propaganda as presented to them by unscrupulous agitators.

Appeal from the People’s Institute to LSRM, March 31st 1921 People’s Institute, 1921-1929; Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; Appropriations, Series 3; Appropriations – Social Welfare, Subseries 3_07; Rockefeller Archive Center; https://dimes.rockarch.org/objects/FSQNDEhv8wgLYguueF8jUE

The Immigration Act of 1924 – The Project of Americanization Loses Steam

The impetus for the Americanization project fizzled largely due to the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act, better known as the Immigration Act of 1924. The Act was one of the most severe in a series of legislative decisions that significantly restricted immigration based on national origin. It placed quotas on several countries and completely excluded Asia, save for Japan and the Philippines. The Chinese Exclusion Act had been in place since 1882, under the prejudiced belief that the Chinese were so racially and culturally foreign that they could not successfully assimilate.

In the end, the People’s Institute’s appeals for additional funds for both the Ukrainian Needlecraft Guild and for the Institute itself were ultimately declined. The Institute received nearly three decades of steady support from the Rockefellers, which was still a remarkably strong record. Yet when Beardsley Ruml came on as director of the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial in 1922, the Memorial’s funding priorities shifted towards field-building and institutional support in the social sciences and away from direct social work. LSRM maintained a depreciating annual donation to the Institute through 1927.

I judge the undertaking, as I have thought right along, to be a worthy one with promise of considerable usefulness both industrially and from a so-called ‘Americanization” point of view […] Apparently this Guild is very useful to a large number of women, has started well, and may become a successful enterprise if financial support can be secured.

I doubt, however, the wisdom of the Memorial’s taking the matter on.

Assessment from W.S. Richardson to Starr Murphy, June 22nd, 1920

People’s Institute, 1919-1920; Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; Appropriations, Series 3; Appropriations – Social Welfare, Subseries 3_07; Rockefeller Archive Center; https://dimes.rockarch.org/objects/kQFL5ZTRwLx8cvHGRWniuG