Precursors to a New Philanthropy, 1892-1913

A Fortune Too Large to Give Away?

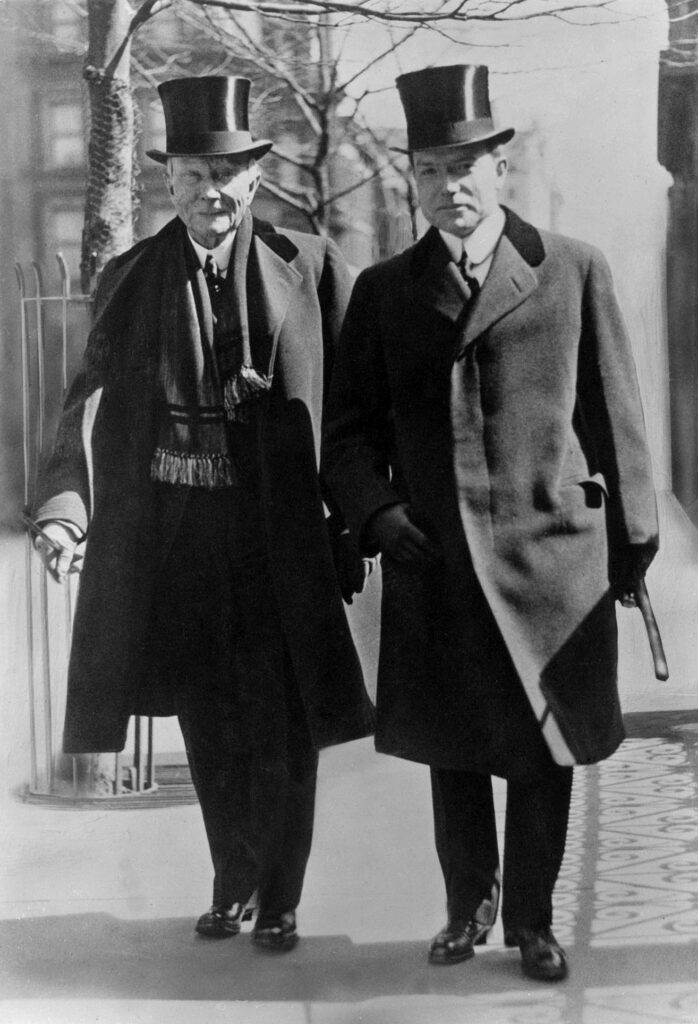

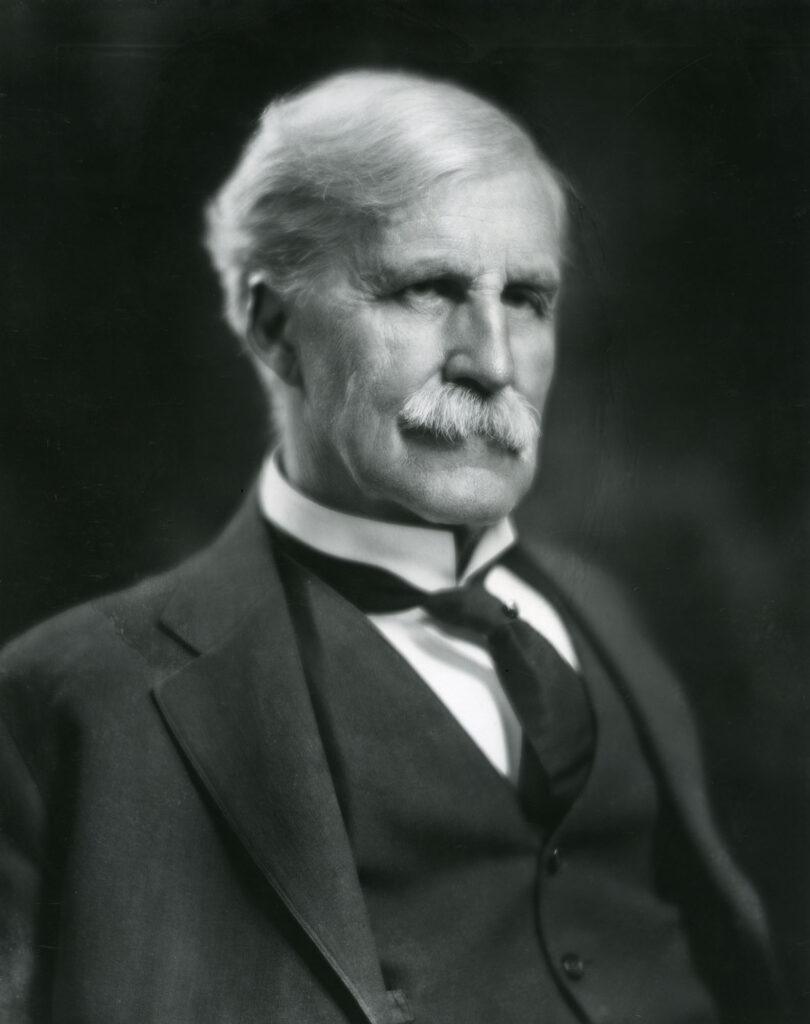

At the dawn of the twentieth century, John D. Rockefeller was the richest man in the world. In a span of only forty years, from his first job as a sixteen-year-old assistant bookkeeper in 1855 to his unofficial retirement as the head of Standard Oil in 1895, Rockefeller not only amassed a personal fortune but transformed American business practices forever. Even after his retirement, thanks to the oil shares he still owned and the demand for gasoline for newly invented automobiles, Rockefeller’s fortune ballooned even further, amounting to roughly a billion dollars by 1913, the year the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) was chartered.

Rockefeller was an ardent, lifelong Baptist and, in keeping with the tenets of his faith, had committed himself to charitable giving as soon as he had any money to give. As he said later in life,

From the beginning, I was trained to work, to save, and to give.

John D. RockefellerAllan Nevins, John D. Rockefeller, Volume I, p. 43, as cited in Raymond B. Fosdick, The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation, (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1952), p. 4.

But by the 1890s, the sheer size of his fortune had turned the process of giving into an impossible chore, as he attempted to respond personally to thousands of individual appeals.

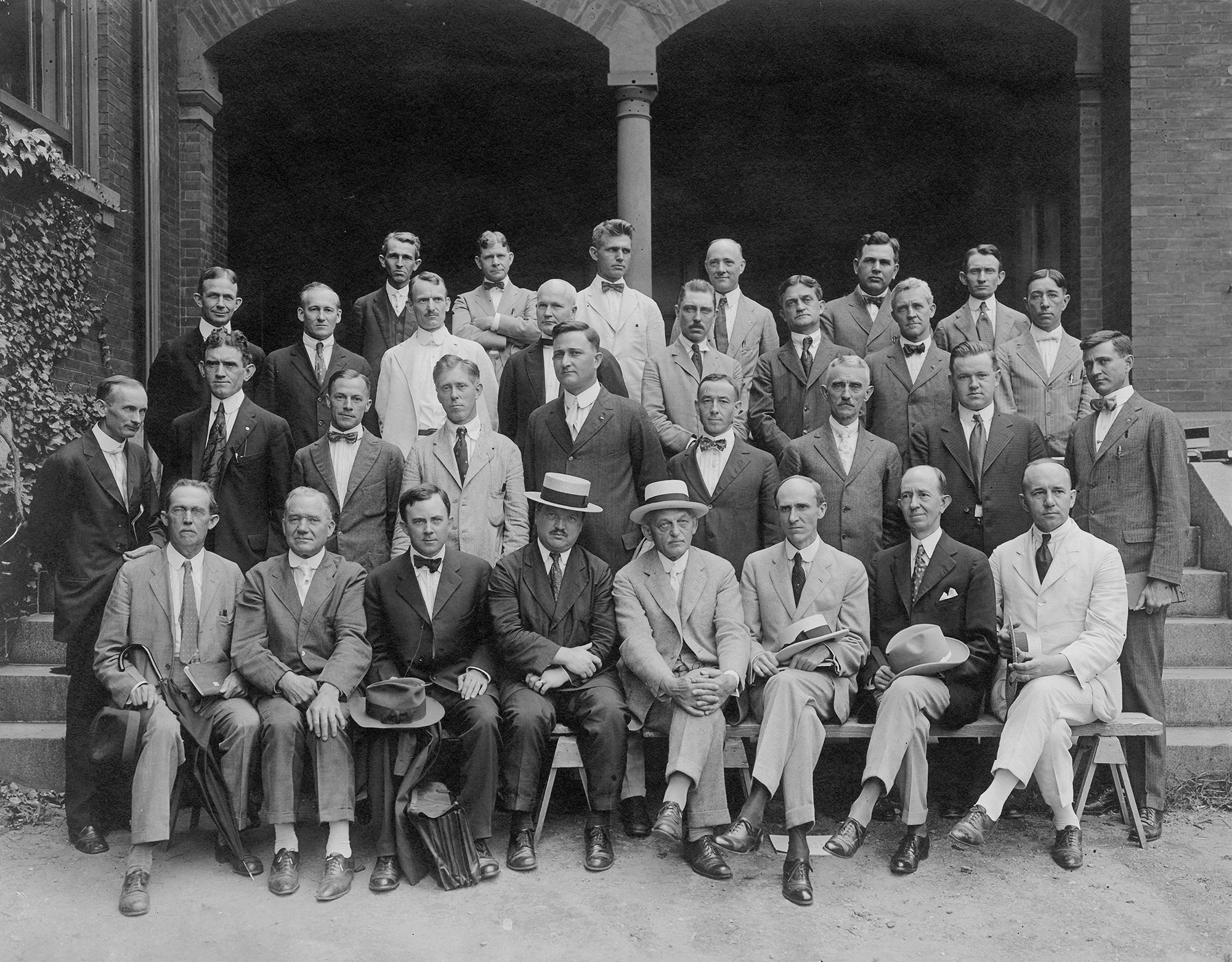

Tackling Root Causes: Making Benevolence a Business

Two men stepped in to help Rockefeller re-envision his ad hoc charitable giving. Together, Frederick T. Gates and Rockefeller’s only son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (JDR, Jr.), worked with Rockefeller to promote the evolution of large-scale philanthropy. They remade personal charity into an organized, institutional enterprise modeled on corporate business practices. This new style of philanthropy did not seek to provide direct relief to the those suffering from disease or poverty, but instead looked to systematic, scientific principles to cure the “root causes” underlying both physical illness and social problems.

As Gates recalled later,

I gradually developed and introduced into all his charities the principle of scientific giving, and he found himself in no long time laying aside retail giving almost wholly, and entering safely and pleasurably into the field of wholesale philanthropy.

Frederick T. GatesFrederick T. Gates, Chapters in My Life (New York: The Free Press, 1977), p. 161.

Progressive Era Values

The new “wholesale” philanthropy was steeped in the ethos of the Progressive era. Ironically, this ethos had evolved in response to the cataclysmic social changes brought about by the large-scale industrial capitalism that Rockefeller himself had helped to invent. Although Progressivism was infused with Protestant religious values, it embraced secular methods, particularly the “rationality” of science and the quantitative analysis of the social sciences. Its essential tools were organization, data gathering, education, and demonstration – all techniques that the new Rockefeller Foundation would zealously adopt.

The quick and unprecedented rise of industrial capitalism created both a vast underclass of low-paid workers and a new middle class that was educated, confident, and more cosmopolitan. By the time of the Rockefeller Foundation’s founding in 1913, this middle class had become increasingly professionalized. The new American middle class tended to put faith in the power of trained experts and created new systems of credentialing in many fields. While attention to social ills aimed to offset the worst effects of big business, members of this class by and large accepted capitalism whole-heartedly. The professional class that would shape the Foundation’s new style of philanthropy aimed to apply the scientific, technical, and organizational solutions born of industrial capitalism to a range of social and economic problems.

Frederick T. Gates Takes the Helm of Rockefeller Philanthropy

Rockefeller first met Frederick T. Gates in 1888 when Gates, an ordained minister, was serving as the head of the American Baptist Education Society. Gates and others were working to convince Rockefeller to fund the creation of the University of Chicago, a gift that would eventually transform a defunct Baptist college into a modern, world-class university. Impressed with Gates’s abilities in business and philanthropy, Rockefeller hired him as his full-time personal philanthropic adviser in 1892. Later, Rockefeller credited Gates with being “the guiding genius in all our giving.”Fosdick, p. 7.

Gates moved quickly to consolidate Rockefeller’s haphazard gifts and began to develop the concepts that would guide his designs for all of the Rockefeller philanthropies: efficiency, strategy, and a centralized system for the distribution of funds.

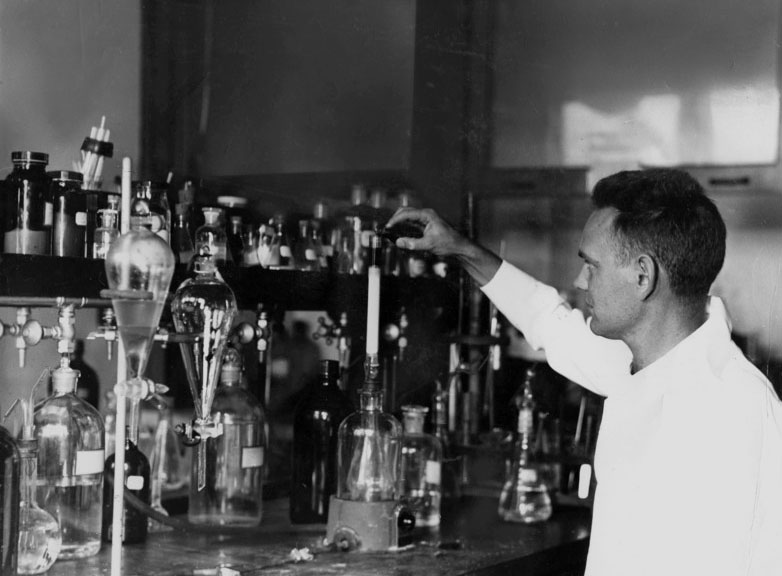

The first institution founded by Rockefeller that bore his name was the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, in 1901. On a vacation in 1897, Gates had read William Osler’s thousand-page volume, Principles and Practice of Medicine, published in 1891. Concluding from it that the state of US medicine — and, hence, disease control — was sadly lagging, Gates envisioned a permanent institution where “qualified men” would be amply paid to conduct uninterrupted scientific research. The Institute, renamed The Rockefeller University in 1965, went on to become one of the pre-eminent centers of medical research worldwide and the site of major scientific breakthroughs, with numerous winners of the Nobel Prize, Lasker Prize, and other awards among the ranks of its faculty.

Three themes evident in the founding of the the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research pervade the Rockefeller philanthropies for most of the twentieth century: the commitment to open-ended scientific research, the idea that research values are universal values, and the conviction that disease is the root of all other ills — physical, economic, mental, moral, and social.

Predecessors in Education and in Health

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. joined his father’s business staff in 1897, but soon found that business was neither his passion nor his talent. The mark he made would instead be in developing the philanthropic side of the Rockefeller enterprises. Between 1900 and 1910, JDR, Jr. and Gates lobbied Rockefeller in tandem, urging him to create a series of “great, corporate philanthropies,” the details of which could be worked out later. Many plans were proposed and discarded as the blueprint for what would ultimately become the Rockefeller Foundation slowly took shape.

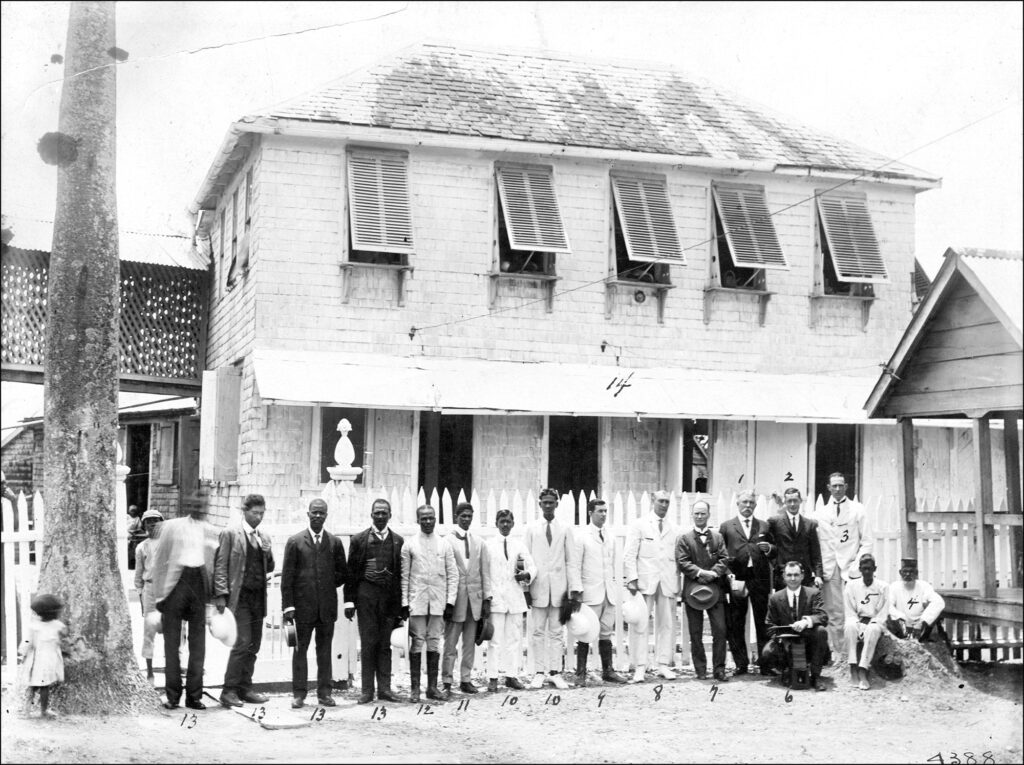

JDR, Jr.’s first project in organized philanthropy came about as the result of a 1900 train tour organized by Robert C. Ogden, focused on African American education in the South. Impressed by what he saw at institutions including Hampton and Tuskegee, but dismayed by the shortcomings of other educational infrastructure for Black students, JDR, Jr. encouraged his father to create the General Education Board (GEB) in 1903. While aiming ultimately to increase educational opportunity for African Americans, the organization quickly understood that it was politically unfeasible in the segregated South to improve the situation for Southern Blacks without including Southern whites in its programs as well, so it set out to strengthen education “without distinction of sex, race, or creed.”“General Education Board: Purpose and Program,” Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), Family Records, Rockefeller Boards, GEB, III 2 O, Box 15, Folder 145.

The GEB exemplified the Rockefeller enterprises’ concern with “root causes.” Although it aimed to improve education, program staff quickly recognized that Southern farmers couldn’t support better schools unless their livelihoods improved enough to raise the tax base to support those schools. In 1906, the GEB launched a wide-ranging and successful farm demonstration program. In 1909, realizing that hookworm disease was rampant throughout the South, and posed a serious obstacle to both education and productive farming, JDR, Sr. established the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm (RSC), to tackle the disease through education, demonstration, and direct treatment.

These two predecessor philanthropies, the General Education Board and Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, established what would become the Rockefeller Foundation’s fundamental methods: demonstration programs and infrastructure enhancement. The GEB demonstration program enabled the US Department of Agriculture to establish a comprehensive system of county extension agents that long outlasted the direct involvement of the GEB. Likewise, the RSC’s campaign to eradicate hookworm disease helped install a county-based public health system that could take on other diseases in future.

Spurred by Success

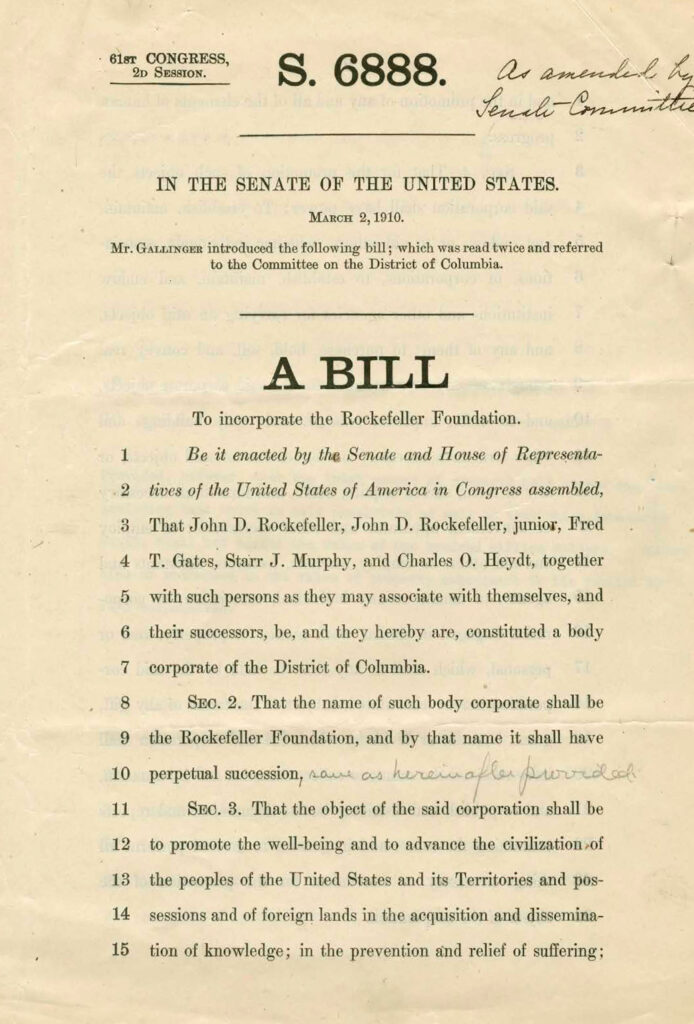

The positive results of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, the General Education Board, and Rockefeller Sanitary Commission reinforced to John D. Rockefeller the benefits of conducting philanthropy on a large scale. These organizations also confirmed the effectiveness of entrusting the disposal of funds to professional staff governed by independent boards of trustees. In 1907, Rockefeller, Gates, JDR, Jr., and family attorney Starr J. Murphy embarked on plans to launch an even broader, multi-purpose philanthropic entity. As they moved to obtain a corporate charter for the new Rockefeller Foundation, they anticipated little trouble. But the nation’s political winds had shifted and the charter struggle would prove to be far more onerous than anyone anticipated.

Finding a Footing, 1913-1928

After a long and unsuccessful quest to obtain a federal charter that played out over half a dozen years, the Rockefellers, Gates, and Murphy agreed to charter their new entity in New York State instead, and the Rockefeller Foundation was incorporated with very little trouble on May 14, 1913. On May 22, the trustees held their first meeting. Throughout the next twenty years, the RF constantly experimented with new program areas and new methods of working. Although Frederick T. Gates had proposed the concept of “wholesale” as opposed to “retail” giving as early as 1901, his idea was more of an inspiration than a blueprint for action. Building a philanthropic enterprise that would run like a business corporation was almost unprecedented on this massive scale.

From the outset, the founders’ ambitions were huge. As Gates put it, “These funds should be so large that to become a trustee of one of them would make a man at once a public character.”Frederick T. Gates, Chapters in My Life (New York: The Free Press, 1977), p. 209.

A handful of similar charitable trusts had been established before the Rockefeller Foundation, including the Russell Sage Foundation (1907) and the Carnegie Corporation of New York (1911), but several things made the Rockefeller Foundation distinct. First was the sheer amount of money John D. Rockefeller transferred to the Foundation: $100 million in the first year plus another $82.8 million in 1919 (the equivalent of more than 5.1 billion in 2022 dollars). By the 1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation had become the largest philanthropic enterprise in the world.

Second, unlike many of its peer institutions, the Rockefeller Foundation had no limits as to the geographic regions or fields of concern in which it could work. The Carnegie Corporation, for example, targeted its giving to the United States and the British Commonwealth. The Russell Sage Foundation focused on “the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States.”

Flexibility also set the Rockefeller Foundation apart from the earlier Rockefeller philanthropies. Where the GEB had tackled education and the RSC the single disease of hookworm, the Foundation’s mission was not specialized, but simply “to promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world.”“An Act to Incorporate the Rockefeller Foundation,” January 23, 1917, “Rockefeller Foundation,” Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center. What that would mean specifically was in the hands of its trustees and program officers. Rockefeller himself never attended a single meeting of the board, explaining that he aimed to avoid exercising too great an influence as the founder, and that each generation would be the best judge of needs and methods during its own time.

Responding to Crisis

The Foundation settled into two main fields of endeavor in this early period: public health and medical education. But the road to these twin commitments was not entirely smooth. Especially in its first four years, the Foundation made gifts to such a wide range of institutions and causes that there seemed to be little unifying theme. And almost immediately, World War I pressed the Foundation into service as a relief organization, despite Gates’s and JDR, Jr.’s earlier determination to avoid charity and aid work. In total, the Foundation spent $22.5 million on war relief work during World War I, more than any other single entity including the federal government.

War work was quite different from the measured, scientific approach to root causes that the Foundation had intended to undertake. It demanded immediate response and direct aid. From 1913 to 1917, the RF underwrote support for Belgian refugees, purchased and shipped food and supplies, and funded training for medical personnel. When the United States entered the war in 1917, the RF dissolved its own War Relief Commission and, from that point forward, channeled war relief funds through the American Red Cross.

International Object Lessons

The Foundation’s war work, however, was not entirely divergent from its core interests. One of the board’s first actions was to establish the International Health Commission (subsequently the International Health Division or IHD) in 1913, under the direction of Wickliffe Rose, who had successfully directed the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission. Rose then applied on an international scale his approach to eradicating hookworm domestically. After a world tour in 1915, he expanded the IHD’s mandate beyond hookworm to include malaria, tuberculosis, and yellow fever.

Just as the hookworm eradication campaign in the US had served as a vehicle for creating a public health system, IHD work also served larger goals. To Rose, the byproducts of the work were more important than the control of any particular disease. As he explained,

…by showing that it is possible to clean up a limited area, an object lesson is given.

Wickliffe Rose, 1915Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report 1915 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1915), p. 14.

These “object lessons” were aimed at changing individual behavior, but perhaps more important, changing the systems and practices of entire communities, with hopes of encouraging local, regional, and national governments to create a public health infrastructure.

In its first ten years, the Rockefeller Foundation became known more for its health work than for any other initiative. RF Secretary Edwin Embree described it as “the outstanding feature of the whole Foundation program to date.”John H. Knowles, “The Rockefeller Foundation 1913-1972: A Brief Review”, December 3, 1973, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 3.2, Series 900, Box 30, Folder 163.He credited its success to Rose’s rigidly enforced procedures, which yielded measurable results of decreased sickness and death rates. The IHD established a simple, consistent methodology even as it mounted extensive and far-flung campaigns. Its fundamental precepts became those of the Foundation as a whole:

- Work in cooperation with government authorities

- Tackle problems that are solvable

- Use demonstrations to persuade governments and other institutions to take over eventually

Building Institutions

The International Health Division’s public health campaigns revealed other, related needs and led the Foundation to new endeavors. Public health work required specialized training that almost no one had, so the Foundation began to create an institutional infrastructure for that training. It established the nation’s first School of Hygiene and Public Health at Johns Hopkins University in 1918, and went on to establish almost two dozen other such schools in the US, Canada, Europe, and Latin America throughout the 1920s.

Like public health training, medical education was not very well-developed in the US when the Rockefeller Foundation began. Medical schools were mostly for-profit enterprises without academic grounding or research facilities. The Foundation’s funding supported full-time professorships within universities and established training programs emphasizing both basic science and clinical subjects. At the same time, the General Education Board gave its support to most of the nation’s leading medical schools between 1913 and 1929, and helped to pioneer the modern, university-based research and teaching hospital. As its commitment to medical education solidified, the Foundation created a Division of Medical Education in 1919, headed by Richard Pearce, with the aim of aiding medical schools throughout the world.

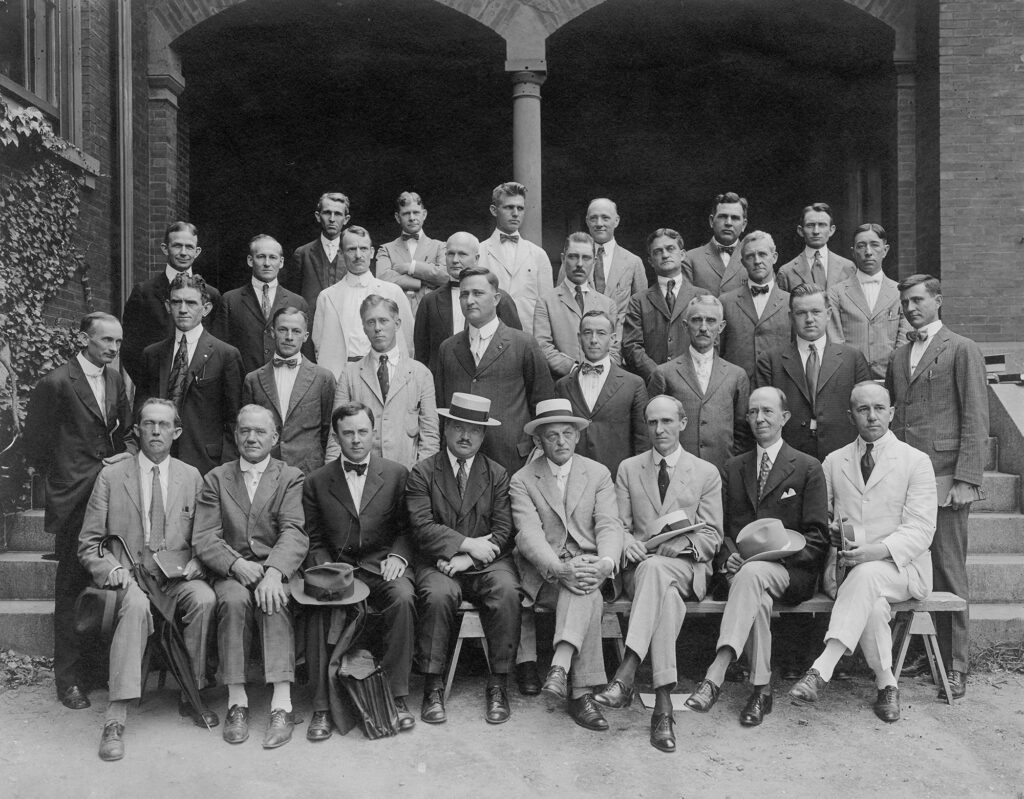

One of the Foundation’s first actions was the establishment of the China Medical Board (CMB) in 1914, and perhaps its most significant endeavor in medical education in a single location. The Foundation’s selection of China as a prime location for introducing Western medicine reflected, in part, the Rockefeller family’s interest in China — a lingering influence of its ties to Baptist missionary work. The CMB enterprise, however, became massive in its own right. After an intensive survey of existing institutions, the CMB decided to build a “Johns Hopkins for China.”Raymond B. Fosdick, The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation (New York, Harper and Brothers, 1952), p. 86.The Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) opened in 1917, received significant RF funding through 1928, and remains the largest single grantee in the Foundation’s history.

“International Trade in Men and Ideas”

In response to the devastation of World War I, Rockefeller Foundation leaders saw the RF role as “tiding over a crisis in the medical sciences,” for a continent whose institutional infrastructure had been decimated.Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1924, p. 48.

The Foundation staff had established significant relationships in Europe during the war, especially through its large-scale campaign against tuberculosis in France. Now they extended those relationships to support individuals in the sciences. In 1923, Wickliffe Rose moved over from the IHD to direct the International Education Board (IEB), a new arm of the Foundation dedicated to promoting education on an international scale. The main idea guiding the IEB was that scientific research was inherently an international concern. The connections needed to foster the development of scientific research had been broken by the war, and the IEB strived to repair them.

Rose developed a hands-on approach: visiting leading scientists, identifying the most inspiring and productive ones, and hiring them to teach the most promising young students (who would, in turn, be supported by Rockefeller Foundation funds). All of the individuals Rose identified were recommended through an extensive network of contacts that Rose constantly nurtured. Rose’s IEB fellowship program would later serve as the model for the Foundation’s support of the sciences in Europe throughout the 1930s under Warren Weaver’s Natural Sciences program. Fellowships remained a central tool at the Foundation for well over half a century, existing in various forms within several programs well into the 1990s and beyond.

“Making the Peaks Higher”

In addition to training individuals, the IEB built key institutions in the sciences throughout Europe, from university departments to independent research centers. Much as he emphasized that the most talented scientists promised the best return on investments, so too did Rose aim to help the strongest of European institutions become stronger. Rose called his strategy “making the peaks higher,” expressing his belief that creating a few centers of excellence would be more effective in his “campaign against human ignorance” than spreading aid more thinly, or working to improve lagging institutions and thereby risking “mediocrity”.Fosdick, “Introduction,” in George W. Gray, Education on an International Scale: A History of the International Education Board, 1923-1938 (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1941), p. vii; and Gray, p. 8.

Bringing Social Knowledge Into the Fold

Although the Rockefeller Foundation’s trustees remained firmly committed to the dual emphases on public health and medical education, the Foundation’s charge to “promote the well-being of mankind” inevitably called for at least some attention to the social aspects of human problems.

A solution arrived in 1918, when John D. Rockefeller established the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (LSRM), named for his late wife, in order to continue her interests in social welfare. It operated as a separate but closely related philanthropic enterprise. Like the General Education Board and the International Education Board, LSRM program officers were in close conversation with those at the RF itself. In 1923, Beardsley Ruml was appointed director and led the LSRM into a role of great influence in the emerging and rapidly developing social sciences.

The LSRM was short-lived, lasting only until 1928, but in that time it laid important groundwork for subsequent RF programs in economics, foreign policy, urban affairs, and cross-cultural understanding. Ruml devised a program of disinterested inquiry into the pressing problems of the day. His program echoed the RF’s position on the hard sciences — that increasing knowledge would naturally lead to progressive and beneficial solutions to all sorts of problems. As Ruml put it,

[S]ocial knowledge is not a substitute for social righteousness, but knowledge is a far greater aid to righteousness than is ignorance.

Beardsley Ruml“General Memorandum by the Director,” September 1922. RAC, LSRM Series II, Box 2, Folder 31, pp. 11-12.

Toward that end, Ruml worked mainly to build an institutional infrastructure for the social sciences. Under his direction the LSRM supported university departments of economics, sociology, and anthropology, and funded the work of non-governmental agencies such as the National Bureau of Economic Research. One of its lasting contributions was underwriting the establishment of the Social Science Research Council.

Next Steps in the Evolution of the Rockefeller Foundation

By the 1920s, there were four Rockefeller boards in active operation: the Rockefeller Foundation, the General Education Board, the International Education Board, and the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial. Many trustees served on more than one, and the priorities of the various boards were often in conflict with each other. Furthermore, the first generation of leadership (which included Frederick Gates, Wickliffe Rose, Wallace Buttrick, Abraham Flexner, and Rockefeller Foundation President George Vincent) was nearing retirement.

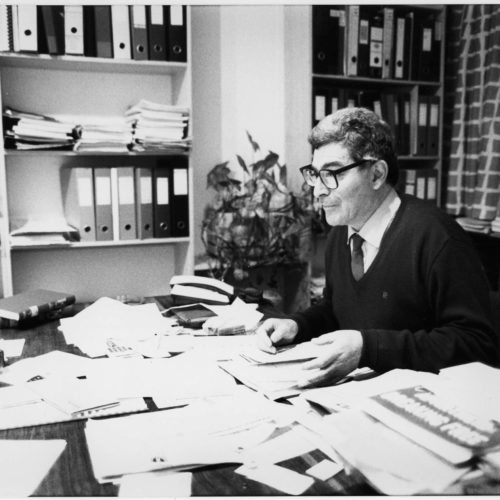

It was time for a recalibration. The first generation had brought the RF to prominence, but these early leaders were not trained philanthropic administrators – in fact, they largely had to invent their profession as they lived it. Their Progressive, reformist zeal had helped shape the Foundation, but the increasingly complex and technical tasks of administration had grown beyond them. Many of them complained about the rote tasks that now consumed their days, and the lack of time for reading, inquiry, and investigation.

Beginning in 1925, President Vincent solicited input from the senior officers on how to reorganize. The trustees formed their own committee for review. Raymond Fosdick chaired the committee and formulated a plan to carry the RF forward. The Fosdick plan, approved in late 1928 to take effect in January 1929, eliminated or absorbed the other boards and centralized control. It also marked a turn toward targeted support for research along selected lines, often through smaller grants. After 1928, the Foundation increased its emphasis on basic research and pulled away from giving large lump sums for buildings and endowments.

The Advancement of Knowledge, 1928-1963

After the major reorganization in 1928, the Rockefeller Foundation entered an era that would in some ways become its defining period. Its operations were now more consolidated than ever and its infrastructure functioned like a well-oiled machine. John D. Rockefeller and Frederick Gates’s vision of a philanthropy that would run like a corporate business had come to fruition.

The 1928 reorganization structured the Foundation into five divisions that were roughly patterned on the academic departments of universities. Most of the related Rockefeller philanthropies, which previously had independent boards, were folded into the Foundation or set free to become independent entities:

- The Division of Social Sciences was created by absorbing the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (LSRM).

- The Division of Humanities took some of its work from the short-lived Division of Studies, and some from the General Education Board (GEB). The GEB itself, which had it own federal charter, could not be absorbed and was given funds to spend down independently.

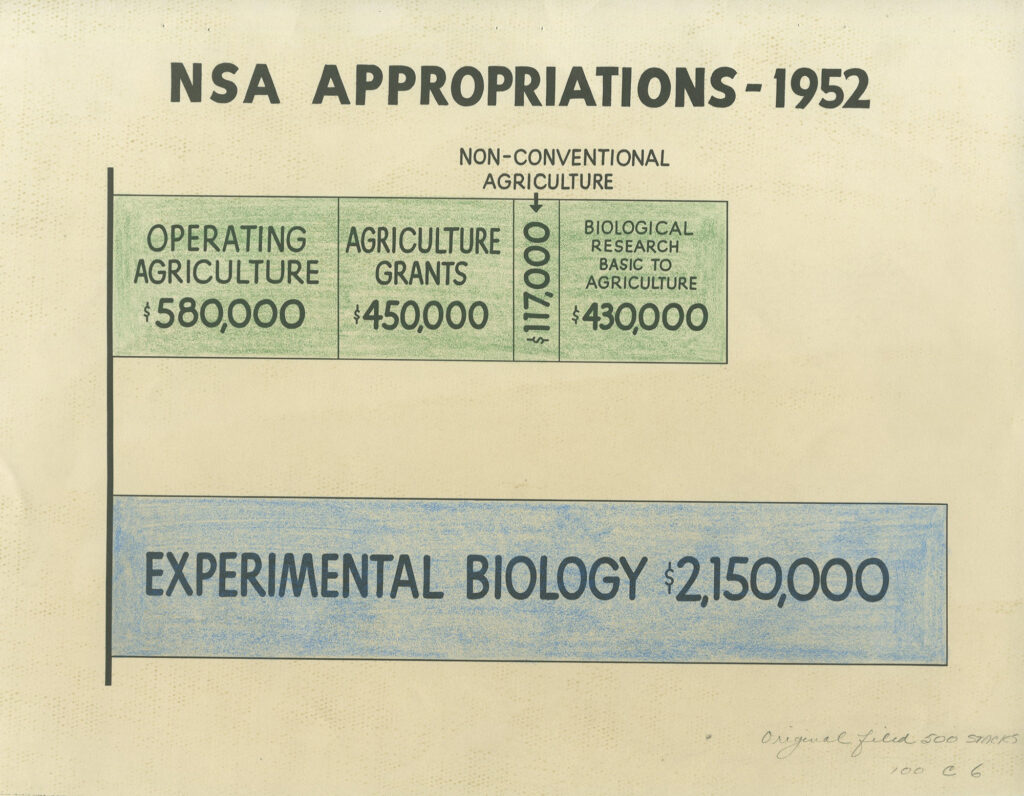

- The Division of Natural Sciences replaced the International Education Board (IEB). It maintained and expanded the IEB’s fellowship program, and developed a new research agenda of its own in experimental biology.

- The Division of Medical Education was renamed the Division of Medical Sciences to emphasize the Foundation’s move toward supporting medical research as well as training; it also began to move into the fields of psychiatry and neuropsychiatry.

- The International Health Division (IHD) continued the longstanding public health work of the RSC and the International Health Commission, and remained the only quasi-independent entity. It was part of the RF but had its own board of scientific directors and full oversight of its annual grantmaking budget.

Without changing its actual mission statement, the trustees adopted the guiding concept of “the advancement of knowledge.”The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1929 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1929)213.This maxim both reflected and extended the Foundation’s longstanding attachment to science. From the 1930s through the 1950s, the RF committed itself to scientific research as a means of enabling human progress. As Raymond Fosdick, the RF trustee and Rockefeller family friend who had engineered the reorganization (and who would become the Foundation’s President in 1936) explained,

It was not to be five programs, each represented by a division of the Foundation, it was to be essentially one program, directed to the general problems of human behavior, with the aim of control through understanding.

Raymond FosdickRaymond B. Fosdick, The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1952), 142.

Yet the Foundation was about to enter a challenging decade. The Great Depression exacted a toll, even on an entity as rich as the Rockefeller Foundation. In fact, 1939 witnessed the Foundation’s smallest-ever return on investments to that date–and hence the smallest amount of income to spend on grantmaking.

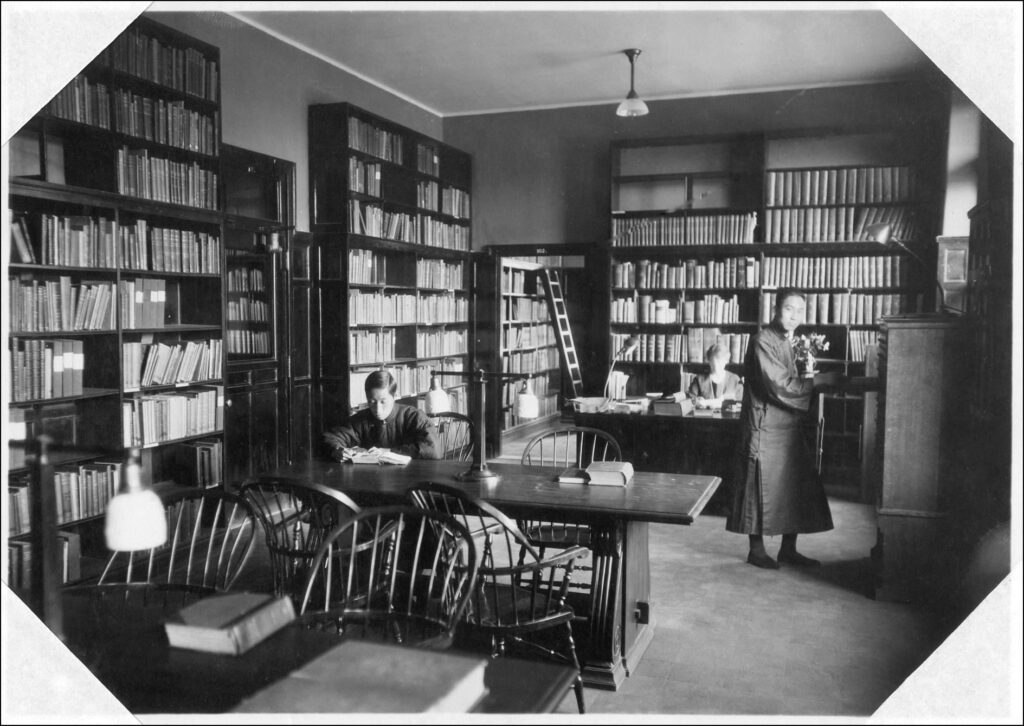

The Understanding of Life

At first, the Rockefeller Foundation’s five division directors struggled to give cohesion to their programs. From 1929 to 1934, they submitted numerous proposals to the board as they worked out the details of evolving ideas. They also grappled with the effect of the Depression on the Foundation’s finances, questioning whether smaller grants might somehow be configured to have a level of impact comparable to the grand sums devoted to institution-building in the Foundation’s early years — the many schools of public health, medical research facilities, new university buildings and libraries the Foundation had funded from 1913 to 1928.

Even with the addition of the social sciences and humanities divisions, the institutional culture of the Foundation remained dominated by science. The program in the natural sciences emerged as the most prominent of the mid-century initiatives. Warren Weaver, a mathematics professor recruited to run the division, undertook a program of self-education in the natural and physical sciences reminiscent of Gates’s immersion in medical science at the turn of the century. Weaver decided that the next great scientific frontier would be biology, which he felt lagged behind the physical sciences and offered the potential to unlock the mysteries of life itself. The multiple proposals he submitted to the board called the new program first the study of “vital essences,” then the “science of man,” before landing on “experimental biology.”The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1938 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1938) 203. Finally, as new technologies enabled the study of smaller and smaller units and the work supported by the Foundation began to bear fruit, in 1938 Weaver coined the term “molecular biology,” to describe the field he had worked so hard to develop, and the term quickly caught on throughout the scientific world.The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1938 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1938) 47.

Wickliffe Rose’s International Education Board fellowship program had been instrumental to the development of the fields of physics and chemistry in the 1920s. Weaver maintained a similar system of support for individuals, and identified fellowship candidates in much the same way as Rose had. He and his field staff constantly visited laboratories across the US and Europe to tap the minds of the era’s leading researchers, and maintained close touch with a vast network of advisers.

But what Weaver now aimed to do was to prompt and foster knowledge transfer, applying the techniques of physics and chemistry to biological problems. Under his direction, the RF funded Linus Pauling’s work on the alpha helix, Norbert Wiener’s work on biofeedback, and Dorothy Hodgkin’s X-ray crystallography, among others. Operating from both New York and the the Paris Field Office, the Foundation’s program officers in the Natural Sciences Division were engaged in some way in most of the atomic and molecular innovations of mid-century science.

The advent of World War II was possibly even harder on the Foundation than the First World War had been. Some RF-sponsored scientific research enabled startling, unanticipated developments, most signally the atomic bomb. The Foundation’s war work this time around involved rescuing and relocating hundreds of refugee scholars from its well-developed scientific network and having to make difficult decisions to bypass many others. As RF officers watched the scientific infrastructure they had helped build in Europe appropriated to serve fascism’s ends, they declared that “reason is everywhere in retreat.”The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1938 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1938) 47.

Post-War Priorities

In the decade following the war, the Rockefeller Foundation redefined its purpose and its areas of work. This represented a significant realignment and redefinition. Universities and foundations had virtually switched places in terms of wealth; where RF contributions had been essential to supporting basic research in the first decades of the twentieth century, several university endowments now dwarfed Foundation resources as did federal funding. The federal government now supported scientific research and administered social programs on a much larger scale than ever before.

On the one hand, these changes were exactly what the RF founders had hoped for: that RF-initiated programs would find government and other institutional sponsorship for the long term. But on the other hand, the RF now needed to find a new role for itself.

New Directions: Agriculture Emerges

The Foundation’s concentration on medicine and public health began to decline after the war and reached a culmination point by the early 1950s. The 1953 retirement of the Medical Division’s longtime director, Alan Gregg, had an impact as well. But the decline also reflected the maturation of seeds the RF had planted early on: medical schools in North America and Europe were now thriving on their own with support from other sources. Many basic public health problems had been significantly ameliorated in Western, developed nations. And furthermore, the creation of the World Health Organization meant there was a new multilateral organization to take on a larger global role similar to the one the RF had played in its early years.

The International Health Division was terminated in 1951, and public health work was transferred to the Division of Medical Sciences, renamed the Division of Medicine and Public Health. In 1959, it was reconfigured again as the Division of Medical and Natural Sciences, with the term “health” phased out altogether. What had been called the Foundation’s “domination by doctors” in its first thirty years had ultimately given way to a new era dominated by agricultural scientists and technicians.John H. Knowles, “The Rockefeller Foundation 1913-1972: A Brief Review,” December 3, 1973, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 3.2, Series 900, Box 30, Folder 163.

How did agriculture, which had not made the cut back in 1928 as a division or even a program of work, come to supplant health at the Rockefeller Foundation?

The Mexican Agriculture Program

The Foundation launched its Mexican Agriculture Program in 1943. The idea had been under consideration since the early 1930s, and its impetus is credited to a remark made by Henry Wallace, the US Secretary of Agriculture. Iowa-born Wallace, a corn breeder himself, asserted that that the best thing anyone could do for Mexico would be to revolutionize the production of corn and beans. By 1943, the instability of Europe made Mexico even more appealing as a safe region in which RF could work. Directed by J. George Harrar, the agriculture program aimed to develop more resilient, disease- and pest-resistant, high-yield varieties of cereal crops, as well as teach Mexican subsistence farmers new techniques that could provide a more abundant and consistent food supply.

The Rockefeller Foundation was particularly well-positioned to run such an enterprise, with almost three decades of experience conducting agriculture demonstration programs in the US and Europe. Yet the program was also a new frontier for the Foundation. It was the first large-scale, long-term operational program other than the International Health Division to be run by the RF directly, rather than a grantee organization. Its salaried staff of plant breeders included future Nobel laureate Norman Borlaug. Eventually, the innovations of the Mexican program were transferred to new programs in other countries in Latin America and, eventually, to Southeast Asia.

The Green Revolution

By the early 1960s, the Rockefeller Foundation, partnering with the Ford Foundation, built on its field work and field research stations in Mexico, the Philippines, and Colombia, and created several international agricultural research institutes, which formed a vast training network through which most scientists working on global agricultural development passed at some point. When hybrid rice developed at the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines helped stave off famine in India in 1966, the entire enterprise stemming from the early Mexican work was dubbed the “Green Revolution”.

The Rockefeller Foundation would be as renowned in the second half of the twentieth century for agriculture as it had been for its health work in the first.

While the work in agriculture was still clearly geared toward Fosdick’s “control through understanding” and continued to rely on bench research, the RF no longer funded open-ended bench science in the belief that it might unlock universal truths about “life processes.” Rather than research for knowledge alone, the agriculture program conducted research toward applied ends.

Responding to the Cold War World Order

After the war, the Foundation’s areas of geographic concern also changed. By the late 1950s, following the shift in programmatic focus to agriculture, Rockefeller Foundation programs wound down in Europe to emerge almost entirely in developing nations in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa. The trustees established task forces to study each region. In 1955, President Dean Rusk mobilized those findings to describe the Foundation’s core themes as “Man’s Physical Environment, Man’s Human Environment, and Man’s Moral and Aesthetic Values.”John H. Knowles, “The Rockefeller Foundation 1913-1972: A Brief Review,” December 3, 1973, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 3.2, Series 900, Box 30, Folder 163.

Rusk, who would go on to become US Secretary of State, was particularly attuned to the issues of the developing world. Throughout the 1950s, many former colonies achieved independence. With the Cold War in full swing, they became contested terrain in the battle between democracy and Communism. Moreover, the economic gap between the developed and developing countries was becoming more and more glaring.

As early as the 1940s, RF staff had identified both food and population as their key concerns regarding this growing gap. As they explored those issues, they also began to support new models for addressing the values to which Rusk alluded. The RF had funded linguistics and foreign language programs since the 1930s. During World War II, these funds increased to spur area studies programs in US universities. These interdisciplinary programs foreshadowed the multidisciplinary turn and the blurring of academic divisional boundaries that would take place across US universities in the 1960s.

Modeled on US Army training programs during the war, area studies provided a forum for social scientific studies of non-Western cultures that could inform and enable democracy-building initiatives and the promotion of civil society.

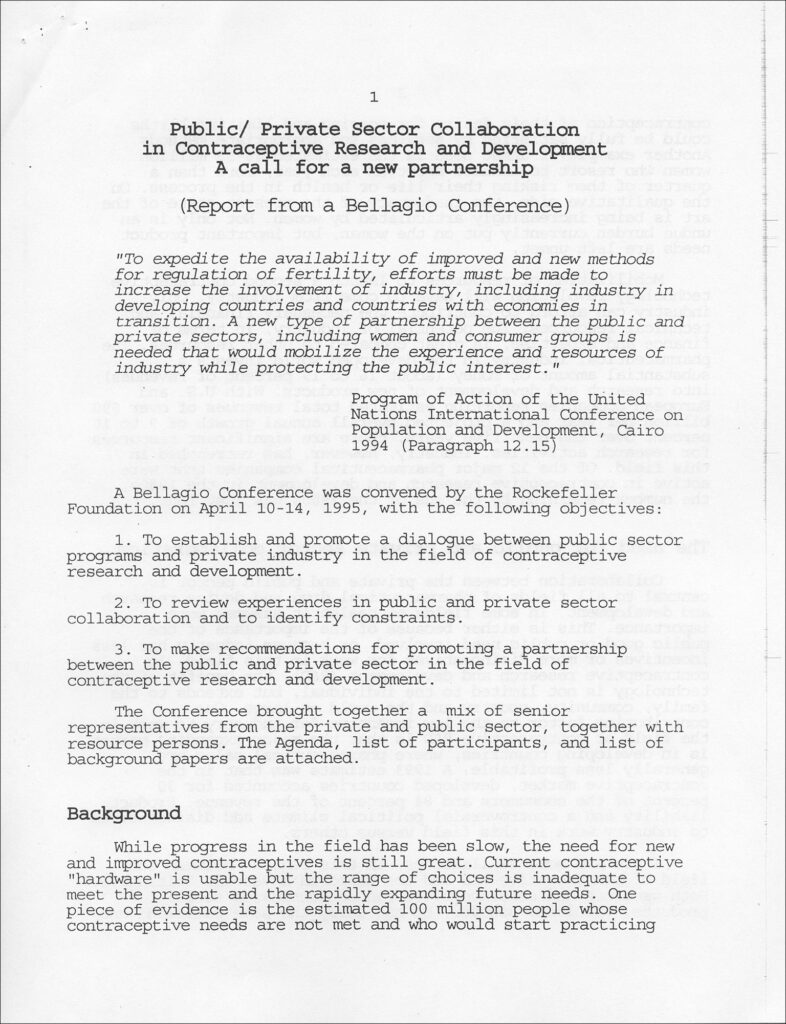

The 1959 gift of an Italian villa on the banks of Lake Como provided an unparalleled venue for a new operating program. To further both its own work and support that of others, the RF transformed the Villa Serbelloni into the Bellagio Center, a venue for international conferences and scholarly and artistic residencies. Although in general the Foundation began to move away from promoting knowledge for knowledge’s sake, the newly acquired Bellagio Center in Italy served as a key place for the exploration of ideas. From the 1960s onward, Bellagio has hosted RF-led collaborative meetings, independent scholarly gatherings, and provided space and time for individuals to accomplish creative work.

The Rockefeller Foundation at Fifty

As the Rockefeller Foundation celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 1963, its leaders once again sought to redefine the organization. As a crowd of prominent guests enjoyed a gala anniversary dinner at New York’s Plaza Hotel, the Foundation undertook a second major reorganization that adopted the interdisciplinary principles it had begun to encourage in universities, as well as an applied emphasis stemming from its agriculture program. The changes of 1963 would fundamentally shape the Foundation’s goals and strategy for the next half century.

An Ecological Web of Giving, 1963-1988

Reorganizing for Changing Times

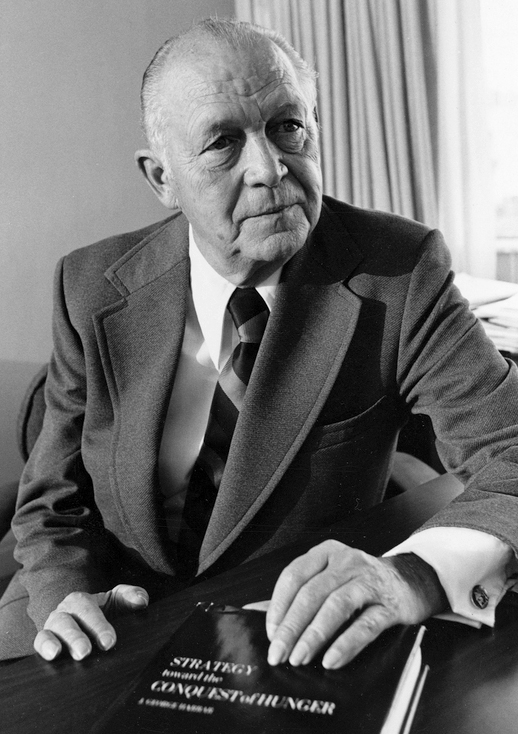

The reorganization at the fiftieth anniversary was led by President J. George Harrar, who had risen to the presidency from beginnings as a local director in the Mexican Agriculture Program. The most significant shift in program organization since 1928, the 1963 reorganization transformed the Rockefeller Foundation’s structure from academic divisions similar to university departments into “goal oriented programs in which each component was related to every other in an ecological pattern.”The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1971 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1971) 10.

It laid out five interdisciplinary endeavors:

- Toward the Conquest of Hunger

- The Population Problem

- Strengthening Emerging Centers of Learning

- Toward Equal Opportunity for All

- Aiding Our Cultural Development

Harrar claimed that these new programs were “not a radical departure from the patterns of the past, but rather the sublimated product of program evolution, set in the contemporary context and projected into the future.”The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1963 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1963) 4.

But they did, in fact, constitute a radical conceptual shift.

The new programs addressed themes that had long been important to the Foundation, but they changed the Foundation’s approach to defining problems and seeking solutions. Discussing these changes several years later, in a review celebrating Harrar upon his retirement, the RF staff noted,

[T]he Rockefeller Foundation had a long history of supporting science and scholarship for their own sakes; now it opted for the application of already existing knowledge toward the well-being of mankind throughout the world….in short,…the Rockefeller Foundation [moved] from the library and the laboratory into the fields and the streets.

Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1971 Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1971 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1971) 5.

The Gospel of Ecology

That Harrar described the new programs as an ecological pattern is typical of this era. By the early 1960s, the rhetoric of ecology had extended beyond the environmental movement. Its concepts became commonplace in academic disciplines and even in popular culture.

The ecological viewpoint, broadly put, cast social problems as complex, web-like systems in which everything was connected to everything else. In the earlier part of the century, taking care of the environment had meant effective stewardship, not interrelationships in which humans were part and parcel of the natural world. Ecology encouraged systems thinking across the board, and unseated the Progressive Era viewpoints that had shaped the RF from the beginning, including older principles of efficient, practical management and benevolent stewardship.

Foundations Under Fire

Harrar was in many ways the ideal candidate to shepherd this transition. A deeply respected leader steeped in the Rockefeller Foundation ethos, he remains the only RF President who has ever risen to the office through the organization’s ranks. He assumed the presidency of the Foundation against a backdrop that included the cultural and social upheavals of America in the 1960s and the controversial Tax Reform Act of 1969.

The Tax Reform Act required increased public accountability from tax-exempt foundations as well as a minimum “pay-out” of funds each year. While the new regulations created difficulties for other foundations, the RF had been meeting the requirements of the new law for years. It had not engaged in the use of funds for political purposes that parts of the law were meant to crack down on.

Probably the real damage the legislation did was to staff morale, as extensive Congressional hearings assailed public confidence in philanthropic institutions, and foundations felt compelled to defend their activities in public. Harrar chafed under the spotlight, arguing that

[W]e consider ourselves a trust, a public trust. That is, we have a social responsibility, and we would like to be understood rather than advertised.

George Harrar, NBC television interview transcript, 1968.

Crisis of Confidence

When Harrar retired in 1972, it was the end of an era. In the early decades of the Foundation, core personnel typically served for long periods of time and played a number of roles along the way. Wickliffe Rose, for example, directed no less than three separate initiatives. Edwin Embree served first as RF Secretary and later as director of the Division of Studies. Raymond Fosdick became a trustee in 1921 and assumed the presidency in 1936. Alan Gregg began as an IHD field staffer in 1919 and became Associate Director and later Director of Medical Sciences, working at the Foundation for 34 years until his retirement in 1953. By the 1970s, such career paths, dedicated to one institution, were no longer the norm. After Harrar, Rockefeller Foundation Presidents didn’t necessarily have a prior connection to the Foundation as a staff or board member. (Richard Lyman (1980-1988) had been a trustee). After 1972, the RF experienced increasingly frequent turnover of both staff and leadership, a trend not unique to the Foundation but mirrored throughout much of the sector, as well as in other industries.

The 1970s witnessed crises of public faith from the Vietnam War to the Watergate scandal to a foundering economy plagued by inflation and stagflation. Environmental degradation, persistent global conflict, crime, poverty, urban decay, and racial inequity seemed intractable. Compounding matters, after the 1969 Congressional hearings, foundations were criticized in the press from every direction and were accused on the one hand of being passive and conservative and on the other, profligate and partisan.

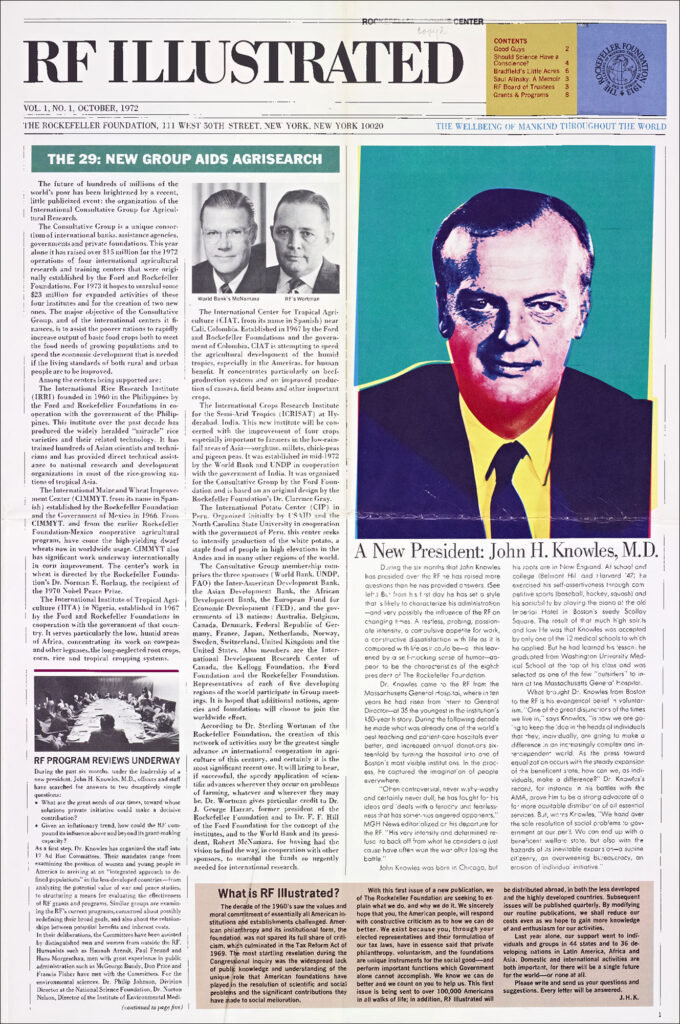

When John Knowles, physician and former head of Massachusetts General Hospital, assumed the RF presidency in 1972, the ideals that had guided the Foundation for most of its history failed to offer the assurance or indeed, the guidance that they once had. Scientific research no longer promised inevitable progress. Knowles referred to “a massive scientific and technological machine run wild” and dismissed quantitative methods as “numeracy and computerized cost-benefit analysis.” He urged a return to the humanities and answers that would emanate from “head, heart and intuition.”NBC television interview transcript, 1968.

Knowles was widely thought to be a surprising choice for president. However, one chronicler of foundations described expecting Knowles to give the RF “a new and less constipated style and its greatest shaking up in half a century.”Waldemar A. Nielsen, The Big Foundations (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1972), p. 70.

Knowles was young, administratively experienced, and outspoken. He immediately launched an intensive program review that took over two years to complete.

The review produced several tense moments that reveal the anxieties of the early 1970s. The trustees were beginning to realize that the Foundation’s traditional method of work with established institutions and government agencies failed to connect with new, grassroots nodes of political and social power. They also noted with dismay that for the first time in RF history, no program contained the word “health” in its title. They quickly attached that word to the Population program despite feedback that it was gratuitous, perhaps reflecting a more widespread feeling that the RF had somehow lost its way. Several program officers wrote to Knowles expressing their feeling that, indeed, that was the case. In the mid-1970s, Knowles instituted weekly informal chat sessions where staff could speak their minds.

In the end, the programs established under Harrar changed very little. Thematic, goal-oriented programs became the norm, although many felt that the divisional structure was never completely dismantled and cross-divisional cooperation was rarely easy. The Foundation continued to run fellowship programs, as well as to both operating and grant-making programs. These longstanding features would gradually and fitfully disappear in the years following the Knowles administration.

What seemed to begin to erode, however, was the Foundation’s clear sense of identity.

Foundation leadership adopted fundamentally new strategies and tackled enormously complex problems with less financial power than they had ever had at their disposal. The stagflation of 1974 hit the philanthropic world hard (the Rockefeller Foundation’s portfolio lost almost half its value), forcing Knowles to use the Annual Report to explain the impact of “the absolute increased cost of problem solving, the devastating effects of inflation, and the emergence of huge sources of public money.”The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1974 (The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, 1974) 8.

All of these factors would force the RF to forge a serious relationship with the concept of “leverage” from the 1980s onward.

Catalyst, Collaborator, Convener, 1988-2013

A changing global economy in the 1980s challenged the Rockefeller Foundation and other private sector organizations and changed their relationship to the public sector. Longtime RF trustee Richard Lyman assumed the Foundation’s Presidency in 1980 and steered the Foundation through a decade that included the emerging global crisis of HIV/AIDS and, in the US, the increasing privatization of social services, including those targeting urban development issues.

Working with diminished financial resources, the Foundation nonetheless succeeded in devising programs that could provide both global leadership and effective strategies to “promote the well-being of humanity throughout the world.”

Forming Alliances

The economic downturn of 1974 precipitated a loss of capital resources for most charitable foundations in the United States, and the RF was no exception. At the same time, the Foundation recognized that one of its key assets was its own history.

The Foundation’s long experience and its vast network of relationships in almost every field rendered it uniquely positioned to identify both pressing issues and potential partners for solutions. The RF also continued to use many of the same research methods it pioneered almost a century earlier. These methods included creating networks of knowledge through meetings for scholars and practitioners, building expertise through training opportunities, maintaining connections to policymakers as well as local stakeholders, and structuring funding to enable grantee organizations to achieve financial independence.

In the 1960s, the Rockefeller Foundation had worked closely with the Ford Foundation to establish agricultural research institutes and to convene several Bellagio Center meetings that launched the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Acting as both convener and catalyst, the RF reactivated this approach through the 1980s and 1990s, including as participants other foundations as well as international governmental and non-governmental organizations. This group then shaped and helped fund independent agencies that supported research in agriculture, disease prevention, population issues, economic equity, and environmental sustainability.

Because these independent agencies did not have the overhead costs of larger organizations with broader mandates, they were able to devote a larger percentage of the resources contributed by organizations like the RF to specific purposes.

Rockefeller Foundation-inspired organizations included the International Agricultural Development Service (IADS), the International Clinical Epidemiology Network (INCLEN), Partners in Population and Development, Leadership for Environment and Development International (LEAD), and the Energy Foundation. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Foundation consistently partnered with the United Nations, the World Health Organization, and the World Bank. One of this collaborative group’s most notable creations was the Children’s Vaccine Initiative.

In 2006 the RF partnered with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to establish A Green Revolution for Africa (AGRA), which works across the African continent to boost small farm productivity and alleviate poverty.

Consistency and Change

Even as new strategies became crucial, the Foundation remained remarkably consistent in the focus of its commitments. Agriculture-related initiatives, for example, were called “Conquest of Hunger,” “Agricultural Sciences,” and “Food Security,” successively. But each phase addressed similar goals: to push research forward, to improve practices on the ground, and to increase farmers’ access to resources and knowledge.

New strategies did prompt change within the Foundation itself.

By the 1980s, the RF had closed most of its field offices (Nairobi and Bangkok remain its main outposts outside New York). It eliminated or outsourced programs that it had operated directly. It no longer employed its own staff of research scientists or oversaw the running of research and educational programs directly. The Foundation sought instead to shape the research agendas of other institutions, identifying and supporting grantees to meet the Foundations’ larger objectives. It also phased out more than six decades of graduate and postgraduate fellowships in the sciences, social sciences, and humanities.

Echoing new models in the corporate and non-profit sectors, the Foundation’s patterns of staffing and board membership also changed. Program officers stayed with the RF for shorter periods of time, working on particular issues or projects in their chosen fields rather than spending their careers at the RF changing roles as needed. Beginning in the late 1980s, under RF President Peter Goldmark, board membership likewise became term-limited rather than a life appointment until the age of retirement, as it had previously been.

A “Knowledge-based Foundation”

Within the Foundation’s institutional culture, program staff had always been encouraged to be thorough, careful, and highly informed. Under President Gordon Conway, appointed in 1996, the RF began to describe itself explicitly as a “knowledge-based” foundation.“The Rockefeller Foundation: A New Course of Action,” by the Rockefeller Foundation, 1999. Fostering knowledge production and exchange was a catalytic approach, a relatively low-cost investment that offered large returns to partner institutions and organizations.

While RF programs had often addressed poverty, in the 1990s the Foundation’s program design became more explicitly about making the world’s poor its core focus. In earlier eras, Foundation leaders had viewed the advancement of science as a means to improve the human condition generally. By 1999, program staff aimed expressly to improve poor people’s lives and livelihoods through the application of knowledge, science, technology, research, and analysis. The Foundation had long supported the cutting-edge technology in every era. As the twentieth century drew to a close, the digital age revealed that poor people’s opportunities suffered particularly from gaps in access to knowledge and technological resources. In the 2000s, the Poverty Reduction through Information and Digital Employment (PRIDE) initiative attempted to redress this inequity in Asia and Africa.

Gender, Diversity and Equity

Beginning with the 1972 appointment of its first female trustee, Mathilde Krim, the Foundation focused more overtly on women’s issues, particularly the special problems affecting single female heads of household. It appointed a cross-divisional President’s Task Force on Women’s Programming in 1981.

But the Foundation concluded that integrating rather than separating women’s issues was more in keeping with its long tradition of tackling the full complexity of any problem. As then-President Lyman explained, this did not mean that the RF viewed gender inequity as a minor issue:

The Rockefeller Foundation does not pretend to be neutral on the questions of gender role or the exploitation and oppression of women. What we do seek is to operate on the basis of knowledge rather than stereotypes. Getting past the heat and into the light on gender issues is itself a worthwhile goal for a foundation. Most of our work is still in progress, but we have been able to demonstrate, for example, that it simply is not true that women are not interested in issues such as national security or that girls ‘naturally’ shun the quantitative sciences.

Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1984The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report 1984 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 1984) 6.

Rather than establish a separate program dedicated to women’s issues, the RF chose instead to tackle gender inequity within each of its existing programs. A major initiative of the 1980s was a six-year demonstration program that trained women heads of household for employment in four cities. Similarly, the key role women play as small-holder farmers in Africa permeated AGRA’s work in the 2000s.

Investing in Community-based Organizations

There were other reasons for Foundation leadership to be concerned with the concept of “leverage.” When the Rockefeller Foundation was founded in 1913, it was one of a mere handful of large-scale philanthropies. By 1982, there were over 22,000 foundations in the United States. Yet these foundations (and their governmental and international counterparts) still struggled to eradicate poverty, hunger, and poor health.

In the United States in the 1980s, as the Reagan administration signaled significant federal budget cuts, the RF pondered its most effective role in a complicated context. For the RF, especially, its historical contributions encouraged high expectations. As then-president Lyman explained in 1982:

To most people, names like Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford, and Mellon connote money, lots of it… Not only are the foundations’ resources wholly inadequate to assume the burdens of the modern welfare state, or even a substantially reduced version thereof, but to look to them for this purpose is to misread their role in American life. That role is not a simple one, given the diversity of foundations as to size, stated aims, and methods of operation.

Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1982The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report 1982 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 1982) 15.

In re-examining its role, the RF began to look to a different kind of grantee. In earlier decades, the foundation had generally channeled its funds through large, established institutions, from university research laboratories to international organizations like the Red Cross. The 1980s and 1990s introduced smaller community-based organizations that worked directly to help the poor gain access to essential goods, services, and economic opportunities. The RF began to support and collaborate within this arena, particularly when it came to issues of urban poverty.

As it had with gender, the RF took an integrated approach to the root causes underlying racial inequity, focusing once again on cities. It connected and collaborated with community-based organizations and sought to improve public schools, access to resources, and employment opportunities. In the late 1980s, the Foundation retooled its ongoing Equal Opportunity (EO) program to examine persistent urban poverty. Based on studies it conducted, the Foundation identified school reform as the root cause that might effect the largest social change. By 1999, it phased out a general EO program in favor of the Working Communities initiative, which aimed to revitalize urban neighborhoods on multiple levels.

The Global and Urban Turn

Rockefeller Foundation work had always been international in scope. In the 1990s, the Foundation began to envision its work as not only international but global, recognizing the interconnectedness of economies, markets, environmental factors, technology-driven communication, and populations. While once it might have been described as an American philanthropy working internationally, its leaders came to conceive of it as a “truly global foundation,” dropping distinctions between international and domestic programs.

At the same time, Foundation staff recognized a global population shift toward cities. They crafted approaches to address urbanization’s interconnected web of poverty, race, gender, education and economics, as well as to city planning and environmental resilience. The complexity of urban concerns — not to mention global social, economic, and environmental problems — required the Foundation to work at a systems level, from multinational to local.

The Living Cities program of the 1990s was a collaborative, public-private partnership focusing on affordable housing and low-income neighborhood revitalization in 23 American cities. As it had in the fields of health and agriculture, the RF served as convener and catalyst, organizing the now-independent National Community Development Initiative (NCDI) to connect federal agencies, banks, and over 300 local community development corporations.

The Foundation’s work in cities became increasingly global in reach, and more integrative in approach as it tackled enormous issues such as transportation and natural resource consumption. In 2008, the RF launched another comprehensive, collaborative initiative, the Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCRN) to enable the world’s most populous, growing, and environmentally threatened urban centers to withstand threats through better mobilization of knowledge for planning.

New Modes of Investing

The RF had always sought strategic investments that would yield the best return for dollars spent. In the increasingly complicated economic setting of the late twentieth century, however, it began to identify a need for new forms of philanthropy. No longer was the divide between the government and private foundations as clear as it once had been. No longer was there even a clear line between for-profit and not-for-profit charitable work or giving. In this context, the Foundation began to partner with for-profit entities in order to effect change for the poor and vulnerable, who often depended on technologies and innovations that were in the hands of the private, for-profit sector.

Cooperation between private, public, and nonprofit organizations began to be accepted across the philanthropic sector as crucial to achieving far-reaching and lasting results. The guiding idea was that, by working together, these organizations could achieve more than any one type could alone. The public sector tended to be slow and inefficient at problem-solving. Free enterprise, while more nimble, often deepened inequities in its drive to earn profits for shareholders. Community-based organizations, while “effective at the local level, [had] difficulty catalyzing change on a larger scale.”The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report 2003 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 2003) 3. Having begun the conversation during the Conway administration, under Judith Rodin the Foundation pushed these ideas even further, convening four meetings in 2008 to incubate the concept of “impact investing,” the mobilization of capital through investment finance mechanisms with the intent to generate positive social impact as well as financial returns.

In 2012, in collaboration with the UN Global Compact, the Brazilian Development Bank, UNISOL, Initiative for Responsible Investment, and Insight at Pacific Community Ventures, the Foundation helped launch the Impact Investing Policy Collaborative. The Collaborative was designed to help investors, public officials, advocates, researchers, and related communities identify and support policies that might result in capital markets becoming more effective at producing intentional social and environmental benefits. In 2013, this effort evolved into he Global Impact Investment Initiative (GIIN), and became an independent entity.

Full Circle

In the opening years of the twentieth century, when John D. Rockefeller and his associates attempted to secure a charter for their new philanthropic foundation, much controversy erupted from the fear that this organization, derived from Standard Oil wealth, would lead to private sector influence, and perhaps actually domination, in the public sphere. For almost a century thereafter, the Rockefeller Foundation strived to remain distinct from corporate enterprise in general as well as Rockefeller family business interests. The opening decade of the 21st century, however, witnessed the non-profit sector increasingly looking to business for solutions. The Rockefeller Foundation, along with others in the sector, worked more and more to mobilize its historic experience and reputation to bring together, on a global scale, the for-profit and non-profit spheres that it once had tried to keep so separate.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “Area and Language Studies Conferences,” 1943-1944 March. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.1, United States – Series 200, Humanities and Arts – Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Yale University – International Relations,” 1931-1943. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.1, United States – Series 200, Social Sciences – Subseries 200.S, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Italian Institute of Historical Studies,” 1948-1953. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, SG 1.2, Italy – Series 751, Humanities and Arts – Subseries 751.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “IADS – MINUTES,” 1975-1985. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Projects (A96), RG 1, Subgroup 1.22, IADS – Series 119, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “IADS – ORGANIZATION AND PLANNING,” 1980-1985. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Projects (A96), RG 1, Subgroup 1.22, IADS – Series 119, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “IADS – ORGANIZATION AND PLANNING,” 1973-1975, 1976-1979. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Projects (A96), RG 1, Subgroup 1.22, IADS – Series 119, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “IADS – ORGANIZATION AND PLANNING – SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL,” 1965-1996, 1980-1996. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Projects (A96), RG 1, Subgroup 1.22, IADS – Series 119, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Organization,” 1914-1948. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Organization Reports – Org-15, Org-16, Org-17,” 1926. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Organization Reports – Org-19 – Org-25,” 1927-1928. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro-27 – Pro-27a,” 1934. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro-35, Working Papers for Pro-35 – Pro-37,” 1942-1946. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Financial Administration,” 1910-1915. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Charter, Constitution and By-Laws,” 1913-1949. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, Charter, Constitution, and By-Laws – Series 902, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Charter, Constitution and By-Laws – Reports – Ch-1 – Ch-3,” 1936-1941. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, Charter, Constitution, and By-Laws – Series 902, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Members and Meetings – Dockets and Minutes,” 1913-1949. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, Members and Meetings – Series 903, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Members and Meetings – Dockets and Minutes,” 1927-1949. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, Members and Meetings – Series 903, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Members and Meetings – Gates, Frederick T.,” 1891-1930. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, Members and Meetings – Series 903, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Members and Meetings – Rockefeller, John D. III,” 1949-1954. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, Members and Meetings – Series 903, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Agricultural Economics,” 1955-1970. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, Social Sciences – Series 910, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro-20 – Pro-24,” 1942-1952. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 1, Natural Sciences and Agriculture – Series 915, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro-46, 47a,b,” 1955-1963. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Reports – Pro-62,” December 3, 1973. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Villa Serbelloni,” 1959-1961. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Villa Serbelloni,” 1962-1967, 1970, 1977. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Villa Serbelloni – Administration,” 1959. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Villa Serbelloni – Administration,” 1968-1970. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Villa Serbelloni – Administration,” 1960-1961 June. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Villa Serbelloni – Program and Policy,” 1961-1970. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, General Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Director, Assistant, Search – A-Z,” 1979. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, Humanities – Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Consultants – Report and Summary of Agricultural Sciences – Field Directors, Meetings,” 1966. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy – RG 3, Subgroup 2, Agriculture – Series 923, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Atomic Energy,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Eliot, Charles W.,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Ellison, Ralph,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Harrar, J. George,” 1960s. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Noguchi, Hideyo,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Page, Walter Hines,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Pearce, Richard M.,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Rockefeller, John Davison, Jr.,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Stakman, Elvin C.,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Groups – China Medical Commission – second,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

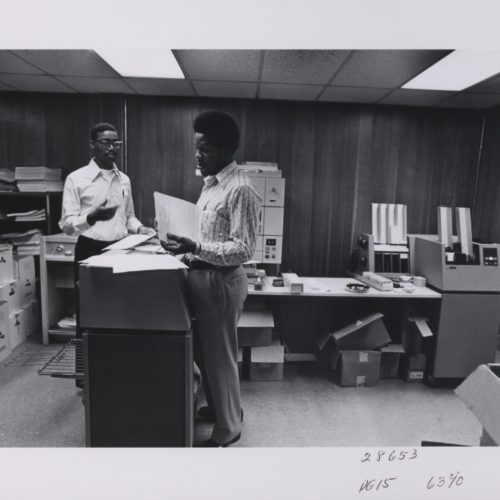

- “Portraits – Groups – Rockefeller Foundation – Christmas Party,” 1965. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Groups – Rockefeller Foundation – 50th Anniversary,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Portraits – Groups – Rockefeller Foundation – New York City Office Blackout,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International – Series 100, Portraits, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “General – With List,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) – Series 115, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Saver – Visit,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, United States – Series 200, – Social Sciences – Subseries 200S, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Corn Improvement,” 1961-1965. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, Latin America – Series 300, Natural Sciences and Agriculture – Subseries 300D, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University College, Ibadan – Broiler House,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, Nigeria – Series 497, Natural Sciences and Agriculture – Subseries 497D, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Rockefeller Foundation – Villa Serbelloni 1960-1964,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs – Series 100-1000, Program and Policy – Series 900, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Italy – Bellagio,” 1959-1991. Rockefeller Foundation records, Communications Office photographs – RG 20, SG 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “JDR – Informals,” 1923-1936. John D. Rockefeller, Sr. papers, John D. Rockefeller, Sr. family photographs – Series 1003, Prints, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “International Agricultural Development Service (IADS),” 1977. L. Sterling Wortman papers, Office Files – Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “International Agricultural Development Service (IADS), Assistance Agencies,” 1976-1977. L. Sterling Wortman papers, Office Files – Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research,” 1971-1972. J. George Harrar papers, Correspondence – Series 1, Collateral Interests – Subseries 1_4, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Latin America,” circa 1954-1966. J. George Harrar papers, J. George Harrar photographs – Series 1019, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “JDR 3rd Album,” 1967-1976, 1967-1976. John D. Rockefeller 3rd papers, John D. Rockefeller 3rd family photographs – Series 1007, Albums, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Fundamental Principles of Philanthropy,” 1908. Frederick T. Gates papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “General Education Board,” 1903-1926. Frederick T. Gates papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Peking Union Medical College 1 – Album,” 1918-1950. China Medical Board, Inc. records, RG 1, China Medical Board, Inc. photographs – Series 1048, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Rockefeller Foundation – Gifts from John D. Rockefeller and Laura Spelman Rockefeller – John D. Rockefeller Deed of Trust,” 1913. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards – Series O, Rockefeller Foundation, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Rockefeller Foundation – Gifts from John D. Rockefeller and Laura Spelman Rockefeller – John D. Rockefeller Gifts,” 1913-1949. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards – Series O, Rockefeller Foundation, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Harrar, J. George,” 1959-1991. Rockefeller Foundation records, Communications Office photographs – RG 20, SG 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Protection of the World’s Children – Conference,” 1983-1985. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, Subgroup 1.12 (A 86), Bellagio Conference and Study Center – Series 120, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “RF 91015 A 45 – FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY – AFRICAN EXHIBITION,” 1987-1996. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, Subgroup 1.23 (A97) – Rockefeller Foundation (RF), Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “RF 91079 A 36 – PAN-AMERICAN AIDS FOUNDATION – COLLABORATION NGO’S AND PRIVATE SECTOR,” 1991-1992. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, Subgroup 1.23 (A 97) – Rockefeller Foundation (RF), Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “RF 88076 – AIDS Initiatives in Africa,” 1988. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, Subgroup 1.24 (A98) – Rockefeller Foundation (RF), Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “RF 91079 A 31 – Columbia University – AIDS Projects in Senegal and Uganda,” 1988-1995. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, Subgroup 1.24 (A 98) – Rockefeller Foundation (RF), Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “AI 9220 – ASSOCIATION OF AFRICAN UNIVERSITIES – HIGHER EDUCATION IN AFRICA,” 1992-1996. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, Subgroup 1.25 (A 99), Subgroup 1.25 – African Initiatives (AI), Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “20 – AIDS VACCINE INITIATIVE – CONFERENCE,” 1993-1994. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1.27 (A2001), Subgroup AC.2001.003, Bellagio Conference and Study Center – Series 120, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “120 – AIDS VACCINE INITIATIVE – CONFERENCE – SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL,” 1993-1994. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1.27 (A2001), Subgroup AC.2001.003, Bellagio Conference and Study Center – Series 120, Rockefeller Archive Center.