This is the story of six decades of attempting to tackle Black education as a means of solving America’s race problem. But despite good intentions and the resources supplied by the vast Rockefeller fortune, work done in acceptance of the framework of segregation fell short of creating true racial equity. Furthermore, the false assumptions driving segregation proved hard to overcome even after the law changed.

The General Education Board

The General Education Board (GEB) was chartered in 1902 with $1 million in funding from John D. Rockefeller, Sr., and charged with improving education in the US “without distinction of race, sex, or creed.”Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

By 1907, Rockefeller, Sr. had increased his contribution to $43 million, making his support to the GEB the largest philanthropic gift in US history at that time. (The founding of the Carnegie Corporation in 1911 with $135 million and Rockefeller’s own $182 million endowment of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1913 would shortly surpass this record.)

Ultimately, the GEB would spend $325 million (roughly $28.4 billion in 2020 dollars) between 1903 and 1964, the year it ended its operations. This included more than $60 million (more than $500 million in 2020 dollars) spent specifically on African American education.

White Philanthropy in the Jim Crow South

While it was not the only philanthropic entity working on schooling in the South — the Peabody Fund and Julius Rosenwald Fund are other notable examples — the GEB outpaced the others in sheer size, scope, and longevity. And, although the Board’s work was to be “without distinction of race,” GEB leadership gave in to Jim Crow segregation, as did the other philanthropies working in the field. The GEB’s adherence to racial segregation, as well as the expectations it held for and communicated to Black students, whether openly or tacitly, has had long-lasting impact on the struggle to achieve true racial equality.

In the words of one historian, the Board quickly acquired “virtual monopolistic control of educational philanthropy for the South and the Negro.”James D. Anderson, “Northern Foundations and the Shaping of Black Rural Education, 1902-1935,” History of Education Quarterly, Winter 1978, Vol. 18, No. 4, 378-79, 380.

Rockefeller’s Entry into the American South

Perhaps surprising to some, the Rockefeller Foundation (the larger and better-known Rockefeller philanthropy) did not launch a program explicitly devoted to racial equality until 1963. Early on, most Rockefeller-funded work on race was conducted by the General Education Board.

Rockefeller’s only son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., thought to create the Board after taking a Pullman train tour across the South in 1901 with other wealthy northern philanthropists, including Henry Ford.William Greenleaf, From These Beginnings: The Early Philanthropies of Henry and Edsel Ford, 1911-1936. Wayne State University Press, 1964. The tour served as a survey of the region’s education system and included visits to several historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Feeling moved to action by what he witnessed, particularly the poverty of the region and the material deficiencies of its Black schools, Rockefeller, Jr. approached his father for funding.James D. Anderson, “Northern Foundations and the Shaping of Black Rural Education, 1902-1935,” History of Education Quarterly, Winter 1978, Vol. 18, No. 4, 378-79. See also “The General Education Board,” The Rockefeller Foundation: A Digital History.

Material Accomplishments…

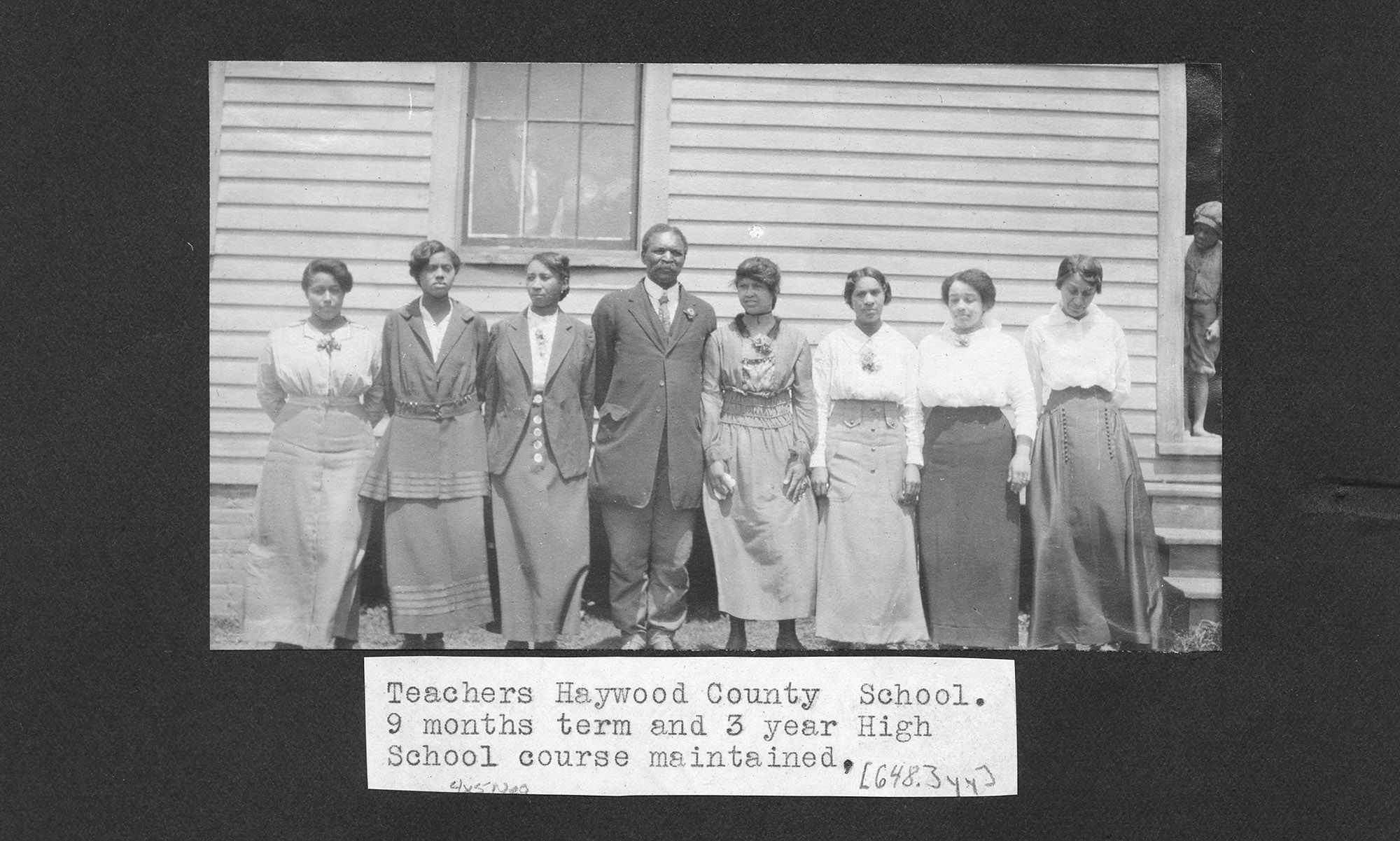

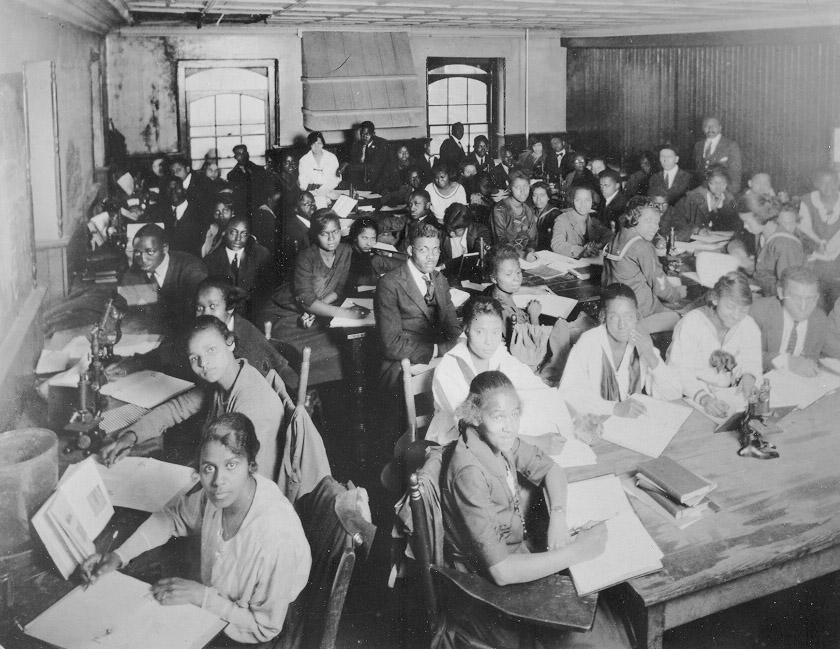

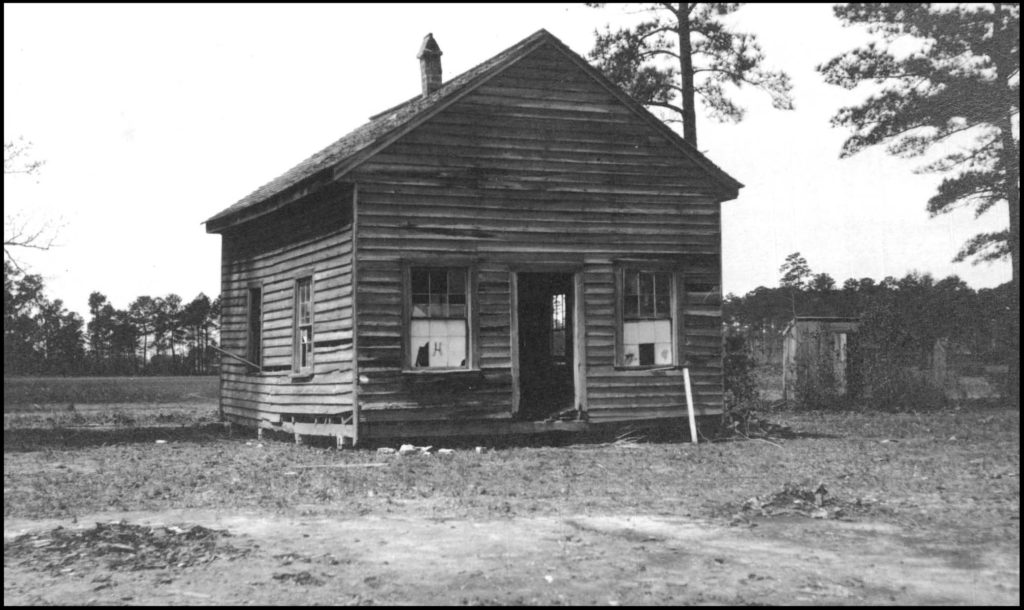

The GEB began with a focus on material improvements to schools, bringing dilapidated one-room schoolhouses into the modern age. In 1912, the Board began underwriting the salaries of state officials who were hired to pay special attention to Black schools. The Board also paid for transportation improvements, funded teacher and administrator salaries, awarded fellowships in teacher education, and built more than 412 high schools throughout eleven states.The General Education Board archives at the Rockefeller Archive Center contain sets of records, listed for every state, as “Supervisor of Rural Schools – Negro – Reports.” They appear in Series 1.1, Appropriations – Early Southern Appropriations.

In an attempt to solve the root cause of the conditions perpetuating substandard schooling, the GEB ran a full-blown agricultural development program from 1906 to 1914 to help improve the economic base for public schools across the rural South.

…but Racist Accommodations

However, working in the South within the bounds imposed by Jim Crow, the GEB built separate schools for white and Black students. The Black high schools were called “county training schools” to appease local whites. In accordance with their name, these schools, unlike white high schools, emphasized vocational training and domestic science over academic subjects.For examples of this, see General Education Board records, Series 1.1, Appropriations – Early Southern Program, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Without a doubt, the GEB had to find ways to work within the limitations imposed by local laws and culture in order to make inroads. Its funds were distributed with the guiding idea of improving schooling for poor whites and Black students simultaneously. Yet the Board’s stated program goals belied the lower expectations that its leadership had for African Americans, as well as their reluctance to address the systems and structures of segregation.

The GEB was criticized for its paternalistic approach by some African American leaders at the time, and has been the subject of further critical evaluation by scholars in recent decades. These critics have reminded readers that the GEB project involved a series of deliberate choices to accept the southern system of racial segregation, and that such choices constrained the struggle for full equality, even while providing Black students with unprecedented opportunities.

Working Under Jim Crow

Before the General Education Board was founded, Rockefeller, Jr. had actually wanted to create a “Negro education board” that would focus solely on Black schooling. But others worried that this approach would trigger a white backlash and doom the project from the start. As Henry St. George Tucker, president of Washington and Lee University and a participant on the 1901 train tour, put it,

If it is your idea to educate the Negro you must have the white of the South with you. If the poor white sees the son of a Negro neighbor enjoying through your munificence benefits denied to this boy, it raises in him a feeling that will render futile all your work. You must lift up the ‘poor white’ and the Negro together if you would ever approach success.

Henry St. George TuckerEric John Abrahamson, Sam Hurst, and Barbara Shubinski, Democracy and Philanthropy: The Rockefeller Foundation and the American Experiment (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 2013), 177.

A White-led Organization Working for Black Education

GEB personnel choices also reflected a cautious approach to racial issues and the realities of segregation under Jim Crow. For example, the State Supervisors for Negro Rural Schools (what would be called superintendents today) were almost always white.

When the prospect of placing more African Americans into these State Supervisor positions was raised, the Board’s response was that such a move would “tend to lessen the dignity of the position in the eyes of the southern white people.” GEB officers recognized that their conservative tactics fell short, but nonetheless believed they offered the only realistic strategy for working in the South. As Wallace Buttrick, a GEB officer from the beginning and its president from 1917 to 1926, explained,

As a matter of absolute justice, they [negroes] ought to participate proportionately with the whites. But…an attempt on our part to compel such proportionate representation now would in all probability defeat our efforts and work to the injury of Negro public school education.

Wallace ButtrickElizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History” (The Rockefeller Foundation: 1985), Richard W. Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Education to “Attach the Negro to the Soil”

With its emphasis on adapting to the South’s racial order, the GEB did not challenge Jim Crow segregation and, furthermore, it took a paternalistic approach to Black education. The Board’s support for industrial education exemplified this stance.

At a time when increasing numbers of African Americans were migrating to urban areas in search of new social and economic opportunities, Board leaders adopted an educational philosophy that, in effect, relegated African Americans to low-wage agricultural work. This approach aimed to stabilize the southern economy and, consequently, to benefit the overall economy of the US. But at the same time, it thwarted Black social mobility and discouraged political activism.

Robert C. Ogden, a GEB president and, from 1894-1913, the president of the Board of Trustees of Hampton Institute, an HBCU specializing in vocational education, went on record as wanting to “attach the Negro to the soil and prevent his exodus from the country to city.”Anderson, 374.

Another early GEB leader, William H. Baldwin, wrote in an 1899 edition of the Hampton Institute’s periodical, Southern Workman, that Black students should “avoid social questions; leave politics alone; continue to be patient; live moral lives.” He went on to say that it was a “crime for any teacher, white or black, to educate the Negro for positions which are not open to him,” and that people in the South already treated African Americans “far better than in any other section of the country.”Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Vintage Books, 1998), 79.

[A]void social questions; leave politics alone; continue to be patient; live moral lives.

William H. Baldwin, 1899

Having led the initial survey of the South’s educational systems from 1902-1904, Wallace Buttrick helped set the course for a GEB approach to Black education that would last for decades. Buttrick held similar views to those expressed by Ogden and Baldwin; he believed in restricting Black education only to certain “useful” fields. He thought African American schools should “teach agriculture and related industries” and support “such training of the Negro for the life that now is, as shall make of him a producer – a servant – of his day and generation of the highest sense.”James D. Anderson, “Northern Foundations and the Shaping of Black Rural Education, 1902-1935,” History of Education Quarterly, Winter 1978, Vol. 18, No. 4, 380-81.

Limited — and Limiting — Expectations

To carry out its work, GEB leadership created three new positions designed to implement industrial education across the South: the State Supervisors for Negro Rural Schools, County Supervising Industrial Teachers, and County Training Schools. Leo M. Favrot, appointed by the GEB to supervise the County Training Schools, justified industrial education by comparing it favorably to slavery, outlining a shockingly racist rationale for this educational approach:

Under the industrial system that prevailed in slavery times the Negroes were not left in ignorance, but were carefully trained along industrial lines…In those days it was to the interest of the slaveholder to train the slave Negro to become efficient. It is no less to the interest of the South today to train the Negro for efficiency.

Leo M. FavrotJames D. Anderson, “Northern Foundations and the Shaping of Black Rural Education, 1902-1935,” History of Education Quarterly, Winter 1978, Vol. 18, No. 4, 378-79, 386.

African American leaders such as W.E.B. DuBois criticized this curricular model, seeing it for the limited and limiting endeavor that it was. In 1911, DuBois lampooned John D. Rockefeller, Sr. for, as he put it, giving southern whites control over African American education.

Later, DuBois criticized Negro Education, a GEB-funded report that promoted industrial education, published by the Phelps Stokes Fund. He denounced the report for advocating “cooperation with the white South without insisting on the Negro being represented by voice and vote in such ‘cooperation.’”Marybeth Gasman, “W.E.B. DuBois and Charles S. Johnson: Differing Views on the Role of Philanthropy in Higher Education,” History of Education Quarterly, Winter 2002, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Winter, 2002), 499. For a good summary of the report, see Diane Ravitch, “A Different Kind of Education for Black Children, The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, Winter 2000-2001, No. 30, pp. 98-106.DuBois also criticized the GEB more directly, writing at one point that the Board was “spending more money today in helping Negroes learn how to can vegetables than in helping them go through college.”Diane Ravitch, “A Different Kind of Education for Black Children, The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, Winter 2000-2001, No. 30, 100.

[The General Education Board is] spending more money today in helping Negroes learn how to can vegetables than in helping them go through college.

W.E.B. DuBois

What About Grants to Black-led Organizations?

Several critics have pointed out the GEB’s failure to support African American organizations working toward Black cultural autonomy and civil rights. In the 1920s and 1930s, when the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History began to incorporate African American history into Black primary and secondary schools, the Board cut the funding it had been providing to the organization. (The Rockefeller Foundation and Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial continued to make grants to the Association, however.)“Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, 1921-1929,” Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records; “Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, 1930-1936,” Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, RG 1.1, Series 100, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The GEB also rejected several requests from the NAACP to support its legal campaigns against school segregation. Jackson Davis, the GEB’s first State Supervisor of Negro Rural Schools, saw the NAACP as a “militant” group that undermined the more gradualist approaches he and his colleagues favored.

Later, in 1939, Rockefeller Foundation President Raymond Fosdick responded similarly to a request for support by the NAACP to desegregate graduate schools. His explanation sheds light on decades of GEB rationale:

The Rockefeller Foundation and the General Education Board have consistently refused to bring any sort of pressure upon the educational institutions to determine their policies and we believe that this is a wise practice to which we should continue to adhere.

Raymond Fosdick, 1939Sarah C. Thuesen, “The General Education Board and the Racial Leadership of Black Education in the South, 1920-1960.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2001.

Fosdick himself later admitted that the GEB “which originally was to have been called the Negro Education Board, did relatively little for the children to whom nature had given darker skins.”Eric John Abrahamson, Sam Hurst, and Barbara Shubinski, Democracy and Philanthropy: The Rockefeller Foundation and the American Experiment (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 2013), 179.

Watch: “One Tenth of Our Nation,” 1940

The Rockefeller Foundation and the Future of the GEB’s Southern Program

By the 1930s, the GEB was one of two Rockefeller philanthropies working expressly on southern race issues (the other was the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, founded in 1917).LSRM, Series 3.8, Appropriations – Interracial Relations, Rockefeller Archive Center.Around this time, however, the Board’s leadership began to plan for the organization’s eventual liquidation. In turn, Rockefeller Foundation officers debated at length whether the Foundation — which focused heavily on scientific and medical research — could or should absorb the GEB’s southern program. At first, the officers hesitated, noting the philosophical and tactical differences between the two organizations.

Where the Foundation had typically directed its funding toward elite institutions of higher education and top scholars in order to “make the peaks higher,” the GEB’s approach was to work with more marginalized and less advantaged groups and institutions. As Flora Rhind, who served in her career as both RF corporate secretary and GEB vice president and trustee, explained:

The Foundation staff people placed a terrific emphasis on excellence…The [General Education] Board was used to trying to raise institutions that were not at the top, and their interests were somewhat different.

Flora Rhind, 1969Flora M. Rhind, Oral History, 1968-1969, Interviewed by Isabel Grossner. Rockefeller Foundation records, oral histories, RG 13, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Warren Weaver, director of the Foundation’s Natural Sciences division, claimed that the “characteristic RF procedure of buying research in the best market leads to exceedingly little Natural Sciences activity in the South.” Weaver also characterized Black schooling as a “self-contained and special interest” that would distract the Foundation from its project of building new, cutting-edge knowledge in the sciences.

The Fate of Rockefeller Money for Black Education

In the 1940s, the Rockefeller Foundation officers settled on a compromise: the Foundation would financially support the GEB’s operations for as long as it could, without actually absorbing the full southern program itself. But even the engagement prompted by simply funding GEB programs produced an unintended result: these programs gave the Foundation real knowledge of the South’s segregated landscape — particularly in education – just as the civil rights struggles that would shape the next two decades began to unfold.

In 1961, at the encouragement of RF president Dean Rusk, the Foundation made a five-year, $250,000 out-of-program grant to the Southern Regional Council, a group devoted to fostering interracial cooperation.Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.3-1.8; Rockefeller Archive Center. The Rockefeller Brothers Fund, a separate philanthropy set up by the children of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., began making grants to the Southern Regional Council in 1954. See, for example, “Southern Regional Council, Inc.,” Rockefeller Brothers Fund records, RG 3: Projects (Grants), Series 1, Rockefeller Archive Center.Rusk was a southerner himself and a seasoned US diplomat sensitive to how Jim Crow was damaging America’s reputation abroad.

But the RF trustees made it clear that this would be a one-time gift and an outlier. Program staff attached a statement to the grant noting that “the Foundation does not as a matter of policy undertake support for an organization devoted to promoting social reform” and the grant was an “exception to this policy in this instance.”Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.3-1.8, Rockefeller Archive Center. See also Elizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History” (The Rockefeller Foundation: 1985), Richard W. Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

A Program for Black Education at the Rockefeller Foundation

As the US civil rights revolution began to take shape in the early 1960s, however, RF leaders began to consider a more robust equal opportunity program. A major proponent of moving forward in this new direction was RF president George Harrar (1963-1972), who told board chair John D. Rockefeller 3rd that the Foundation had to begin working more on contemporary social issues — and not only in academia.

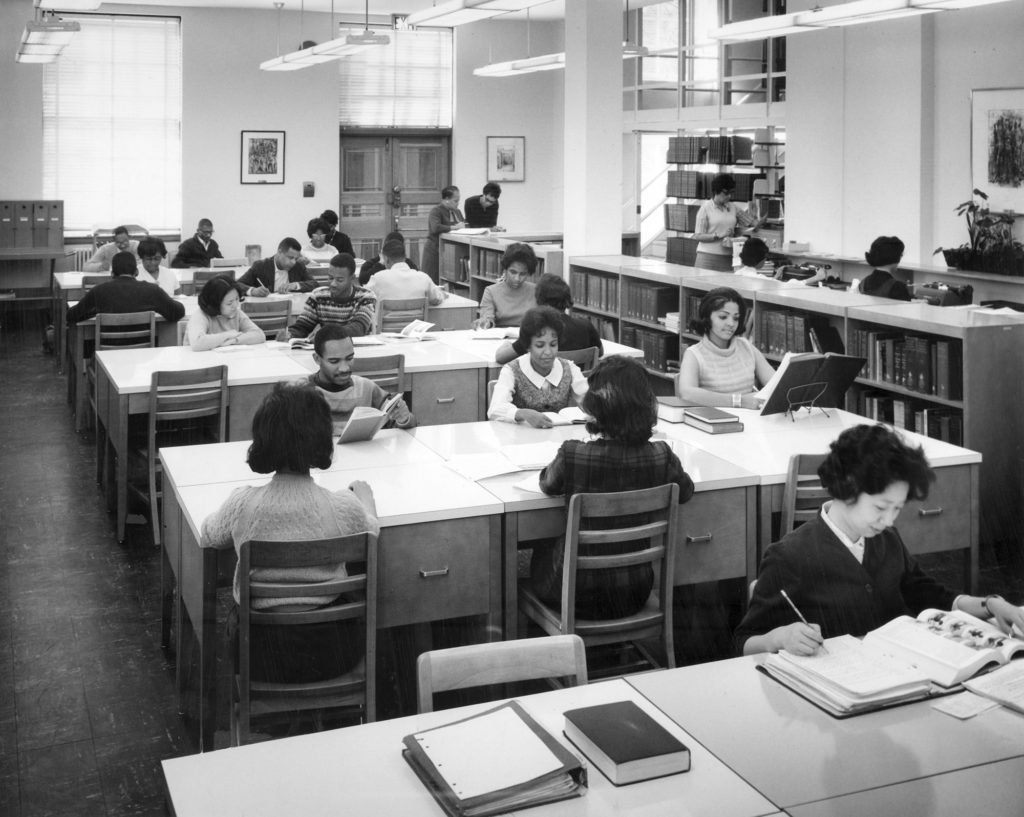

Given the GEB’s work and the Foundation’s own history, most agreed that education was the place to start. However a vigorous debate erupted over two issues: first, whether the RF should channel its support to HBCUs; and second, whether the Foundation should work to improve K-12 public schools. Initially, those tasked with launching the new EO program said “no” to both. RF officers believed — mistakenly, in retrospect — that most HBCUs were subpar institutions that would soon become obsolete after desegregation was finally implemented.

Racial Justice or “Opportunity?”

Eager to form a program quickly, the RF’s new race-related program, Toward Equal Opportunity For All (EO), by and large avoided a deeper engagement with the complexities of racial injustice. Instead, the new initiative aimed quite simply to provide “disadvantaged citizens with better educational opportunities.”

As its name suggests, the Equal Opportunity program promised individual access to education and its attendant benefits. It focused on diversifying the student body of white academic institutions rather than advocating for systemic change to those institutions.

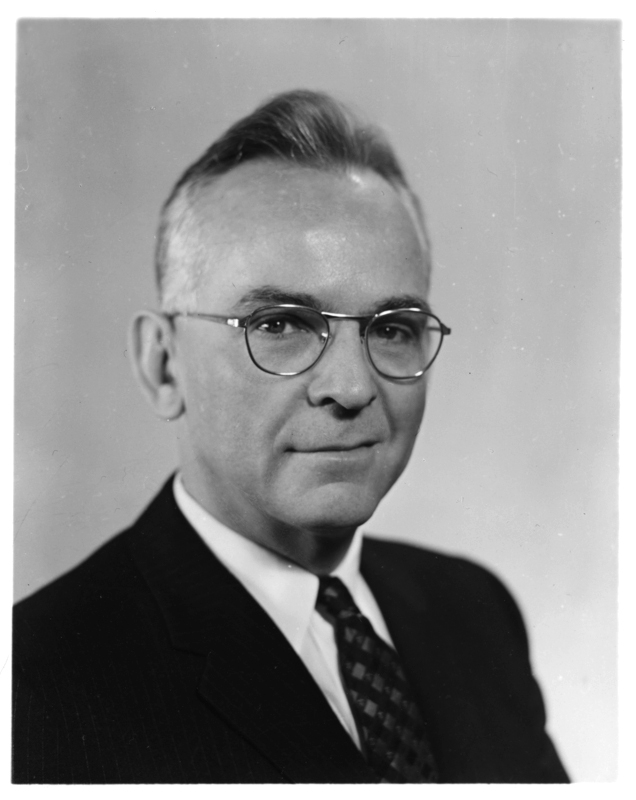

Leland DeVinney, who directed the EO program from 1963-1969, worked firmly out of the old, longstanding RF philosophy of “making the peaks higher.” DeVinney thought any potential program should focus on helping elite (and therefore white) universities recruit high-achieving African American students. In a 1963 memo, he described the need to identify “people and institutions of highest quality and potential,” the “ablest candidates,” and “the most talented students.”Leland DeVinney to Kenneth W. Thompson and George Harrar, June 24, 1963, “RF Aid to Negro Education in the United States,” Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.29, Series 900, Program and Policy – Equal Opportunity, 1959-1973, Rockefeller Archive Center. See also the fully digitized volumes of Leland DeVinney’s officer diary available in the Rockefeller Foundation records, officers’ diaries, RG 12.DeVinney believed his strategy would slowly but surely desegregate higher education and the American workforce.

The Foundation’s earliest EO grants were cautious and DeVinney himself would come to criticize them in retrospect, for not going far enough to confront racial inequality.

Two notable examples of this kind of grantmaking stand out: $250,000 each to Emory, Duke, Vanderbilt, and Tulane to provide scholarships for qualified Black students; and a $150,000, three-year grant to the Princeton College Summer Program, one of three grants supporting academic summer programs for Black students.The files for these grants, for “student assistance” are located in SG 1.3-1.8, Subgroup 8, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center. See also Elizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History” (The Rockefeller Foundation: 1985), Richard W. Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.Both projects illustrate the limitations of the “exceptional student” approach to EO work in education.

Diversifying Higher Education Begins Elsewhere

In the first case, DeVinney and admissions officers at Emory, Duke, Tulane, and Vanderbilt quickly encountered difficulty in recruiting African American students using their existing evaluative standards. Black high schools often lacked the resources to prepare students for college, and thus the white admissions officers did not have appropriate means even to measure Black students’ potential.

Once admitted, these select few Black students often struggled on campus. Duke’s admissions director recalled that students had difficulty adapting to college life, and to what he saw as the more rigorous college curriculum. He began to recognize that the diversification of top universities needed to begin long before the college admission process and that the key to true diversification was in structural reforms to primary and secondary schools. “In the early 60’s,” he reflected two decades later,

I believed that with clever programs of remediation you could overcome past deficits. I found I was mistaken…The middle-class system places a high value on education, but the system hadn’t been there for those kids.

Admissions Director, Duke UniversityElizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History” (The Rockefeller Foundation: 1985), Richard W. Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Another Failure for Black Students

The Princeton College Summer Program (PCSP) yielded a similar lesson. A six-week summer enrichment program billed as a “remedial education” program, the PCSP aimed to increase Black students’ academic confidence and build skills for college, while demonstrating simultaneously to colleges that minority youth were capable of intensive collegiate work. Initially, PCSP administrators were optimistic that, after six weeks at Princeton, these students, who had been selected for being outstanding in the first place, would return home and help raise the overall quality of their neighborhood schools. Such unrealistic expectations proved far too much for students to shoulder, and no real change occurred in the schools.Princeton, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center; Oberlin, SG 1.3-1.8, Subgroup 4, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

DeVinney eventually came to admit the shortcomings of his strategy, which had assumed that simply widening the door of access to higher education for already high-achieving minority students would “trickle down” to help solve systemic racism in America. He reflected,

We proceeded at that time under the naïve assumption that we could solve the problem of unequal opportunity by going out and finding these ‘nuggets’ as we used to call them – the Ralph Bunches and Jackie Robinsons of the minority groups… Over the years, it became apparent that there weren’t all these academic nuggets turning up, but that took a long time.

Leland DeVinney, 1985Elizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History” (The Rockefeller Foundation: 1985), Richard W. Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

DeVinney’s realization was not that Black students didn’t hold the same potential as any other students. Over time, what he came to understand was that the system itself had failed Black students by failing to provide them with the conditions necessary to excel. Making up for that would require far more than a summer program, or a grant aimed at raising college admissions numbers. Moreover, from today’s standpoint of critical race theory, DeVinney and his colleagues never achieved the most crucial bit of understanding: that the very benchmarks they used to measure excellence might themselves have been racist, and would never have provided the right framework for enabling Black students to succeed.

A Naïve Assumption about Educational Opportunity

Eventually, Princeton and Rockefeller Foundation leaders did come to see their “enrichment” plan as well-intentioned but off-base. As a later report explained:

Our most notable lack of success has been our inability to effect any significant changes that would improve education on the secondary level. While it was obvious that a program of relatively small scope […] could not hope to bring massive changes in the high schools, it was believed that these structures would be responsive to our offers of support. […] Time has proven this assumption to be certainly untrue and perhaps somewhat naïve.

Leland DeVinneyElizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History” (The Rockefeller Foundation: 1985), Richard W. Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

“Whistling Dixie While the Country was Burning”

By the late 1960s, Rockefeller Foundation officers began to feel that the Foundation had failed to make any real inroads to improving either education or inner-city poverty. This feeling was driven home by the riots that erupted in Watts in 1965 and again in the “long, hot summer” of 1967 in Newark, Detroit, and other US cities. (These uprisings were triggered by confrontations between white police officers and African American motorists). According to one commentator, the shifting political landscape led the Foundation trustees to realize that it had been “whistling Dixie while the country was burning.”Elizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History” (The Rockefeller Foundation: 1985),” Richard W. Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Although a special trustee-staff joint committee was convened in the fall of 1967 to reshape the EO program, and it met with civil rights leaders, scholars, and public intellectuals, the reorientation it proposed toward inner-city poverty, low-income neighborhoods, and new community experiments in school reform never really took off.

From Black Education to Economic Opportunity

RF president Harrar retired in 1972 and was succeeded by physician John Knowles. With the stated goal of shaking up a Foundation that was now widely perceived as stodgy and out of touch with the times, Knowles took a more activist approach to leadership. He was only the second president of any major US foundation to visit the South personally to plan work in racial equity. But Knowles died unexpectedly from pancreatic cancer in 1979, and many of his program ideas never had the chance to come to fruition.

By the 1980s, the civil rights landscape had changed. In response to the sea changes of the 1980s, in particular the Reagan administration’s attacks on the welfare system, the Rockefeller Foundation moved away from working in education and toward cultivating more equitable economic opportunity — a focus that still guides its its work today.

Further Reading

- Huimin Wang, “Psychologizing School Problems: The Science of Personality Adjustment in Interwar U.S.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020

- Kimberly Anne Probolus-Cedroni, “Separate and Unequal: Giftedness in the United States 1900-2000.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Edward-John Bottomley, “Training Poor Whites: The General Education Board and Southern Education.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2017.

- Daniel Huebner, “Philanthropic Funding and Field Agents in the Development of Teacher Education Institutions.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2016.

- Kate Sohasky, “Capitalizing I.Q.: Intelligence as Human Capital in the Twentieth Century.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2015.

- Elizabeth Lundeen, “The General Education Board’s Involvement in Higher Education for African Americans: The Case of North Carolina College for Negroes, 1909-1930.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2014.

- Craig Kridel, “Progressive Education in the Black High School: The General Education Board’s Black High School Study, 1940-1948.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2013.

- Thomas Adam, “The Scholarship Program of the General Education Board from 1950 to 1954.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2013.

- Karen Flynn, “African American Nurses and Travel: Collaboration and Social Remittances.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2012.

- Jonna Perrillo, “Teacher Research and the Rockefellers.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2012.

- Mark Schultz, “The Battle for the Schoolhouse in Jim Crow Georgia.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2010.

- Kenneth W. Rose, “The Problematic Legacy of Judge John Handley: R. Gray Williams, The General Education Board, and Progressive Education in Winchester, Virginia, 1895-1924.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2008.

- Sarah C. Thuesen, “The General Education Board and the Racial Leadership of Black Education in the South, 1920-1960.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2001.

- John Kayser, “The Early History of Racially Segregated, Southern Schools of Social Work, Requesting or Receiving Funds from the Rockefeller Philanthropies and the Responses of Social Work Educators to Racial Discrimination.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2000.