An Appeal

In December 1962, William Gossett, Chairman of the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), sought a meeting with Rockefeller Foundation (RF) officials to discuss an upcoming fundraising campaign.Bayard F. Pope to George Harrar, “United Negro College Fund, Inc.,” Rockefeller Foundation records, SG 1.2, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

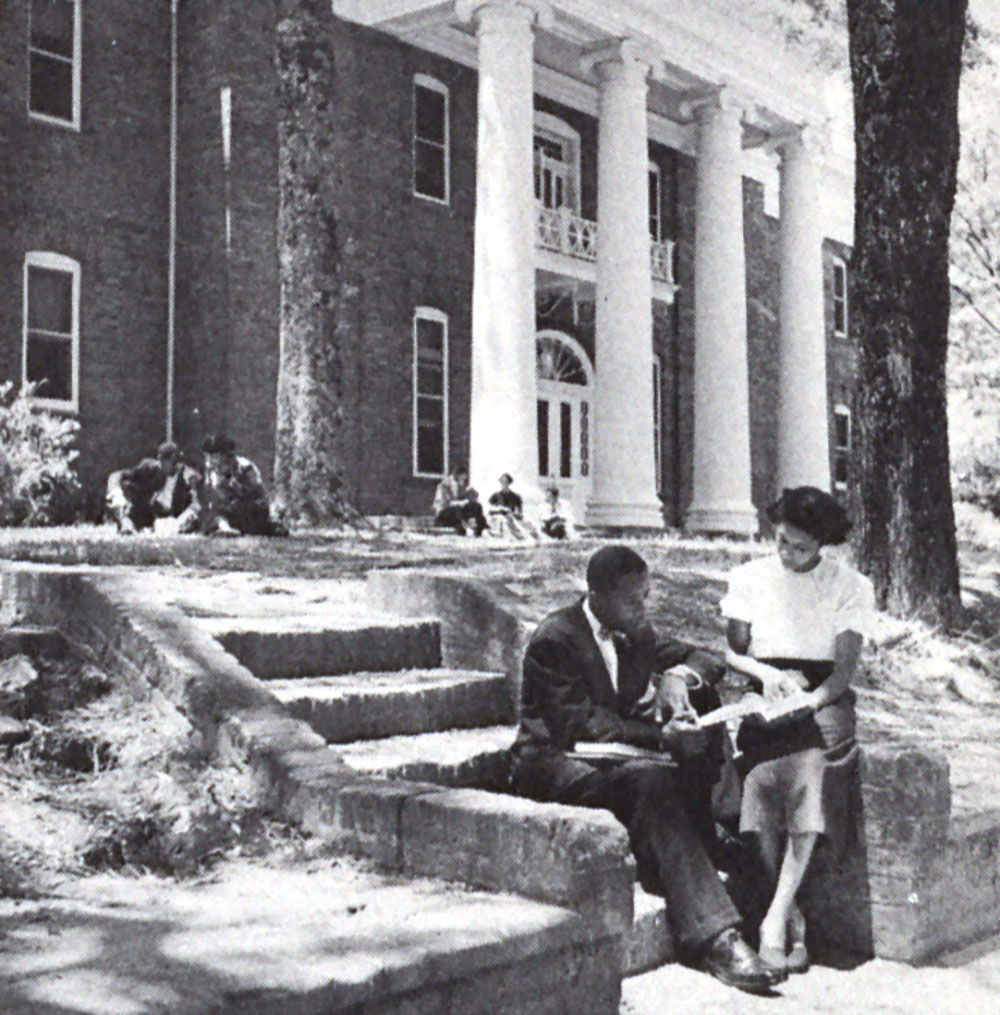

The UNCF is a consortium of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). At the time, it had thirty-three member institutions; in 2019 it comprises thirty-seven. Gossett’s letter ultimately prompted the RF to create its first program devoted explicitly to social justice issues, a program that would be entitled Toward Equal Opportunity For All (EO), and would aim to provide “our disadvantaged citizens better educational opportunities.”“Excerpt from ‘Plans for the Future – A Statement by Board Members of the RF, Adopted at a Board Meeting,” September 20, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.29, Series 900, Program and Policy – Equal Opportunity, EO-1 Through EO-7, Rockefeller Archive Center.

To some extent, the new program signified the RF’s attempt to change with the times. The Foundation historically had supported elite institutions of higher education, and even in those settings, it had focused its efforts primarily on research. As Wickliffe Rose, head of an RF sister philanthropy, the International Education Board (IEB), noted in the 1920s, this approach sought to “make the peaks higher” around the globe. Working with the best of the best, Rose and his RF associates believed, was the key to achieving real innovation.

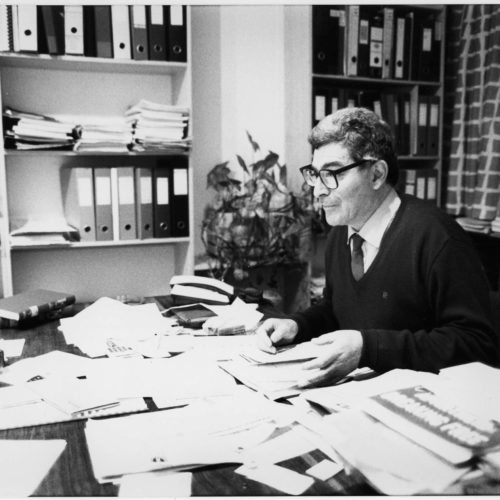

The Foundation people placed a terrific emphasis on excellence. They were used to dealing with the top institutions in the field.

Flora Rhind on RF’s traditional programmatic focus

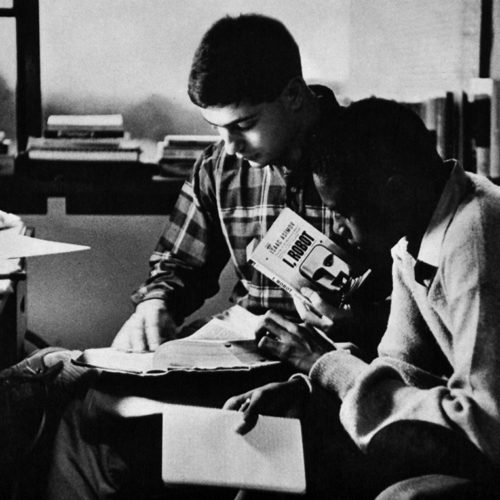

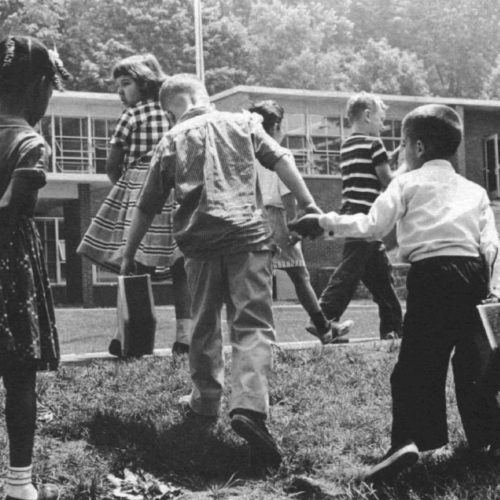

But in the 1960s, struggles for racial equality had cohered into a globally-recognized civil rights movement that brought renewed attention to segregated schools and educational inequality, issues that did not align neatly with the Foundation’s traditional focus on elite institutions.

Nevertheless, this changing political climate — magnified by direct appeals from President John F. Kennedy to support the UNCF drive, as well as the participation of several other foundations — ultimately altered RF strategy.

Earlier Rockefeller Support for HBCUs

Rockefeller family philanthropy (distinct from the RF) had long supported HBCUs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and his son, John D. Rockefeller 3rd, had chaired the Fund’s advisory committees and contributed millions to UNCF fundraising campaigns since the 1940s, as had JDR 3rd’s brother Winthrop Rockefeller.“United Negro College Fund,” Rockefeller Family Public Relations Department papers, Series 13, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Support from the General Education Board (GEB), created by JDR, Jr. to promote educational improvement in the American South, began even earlier. Since 1903, the GEB had provided over $60 million for African American schools and educational support organizations, including the UNCF.“Support of Negro Education from Date of Founding in 1902 to April 30, 1963,” Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.29, Series 900, Equal Opportunity – Program and Policy, 1959-1973, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Despite the long involvement of these other Rockefeller entities, however, the RF itself had never made support for historically black institutions – or other matters explicitly related to racial equality – a priority.

Instead, Foundation leaders viewed these issues as falling exclusively under the purview of the older GEB. Flora Rhind, who worked for both the RF and GEB, recalled this important distinction: “The Foundation people placed a terrific emphasis on excellence. They were used to dealing with the top institutions in the field. The [GEB] was used to trying to raise institutions that were not at the top, and their interests were somewhat different.”Elizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History,” 21-22, Richard Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

However, several factors pushed the RF to absorb programming that had previously been the province of the GEB. Many program officers held joint appointments in both organizations. The GEB began to spend down its funds in the 1940s, and the Foundation began to pick up the slack on some key GEB initiatives. By the early 1960s, some hoped the RF would officially take over all GEB programs in the South. ibid., 22-34

RF leaders received the UNCF inquiry just as they contemplated the fate of these programs, roughly one year before the GEB would close its books.

But would the RF support HBCUs?

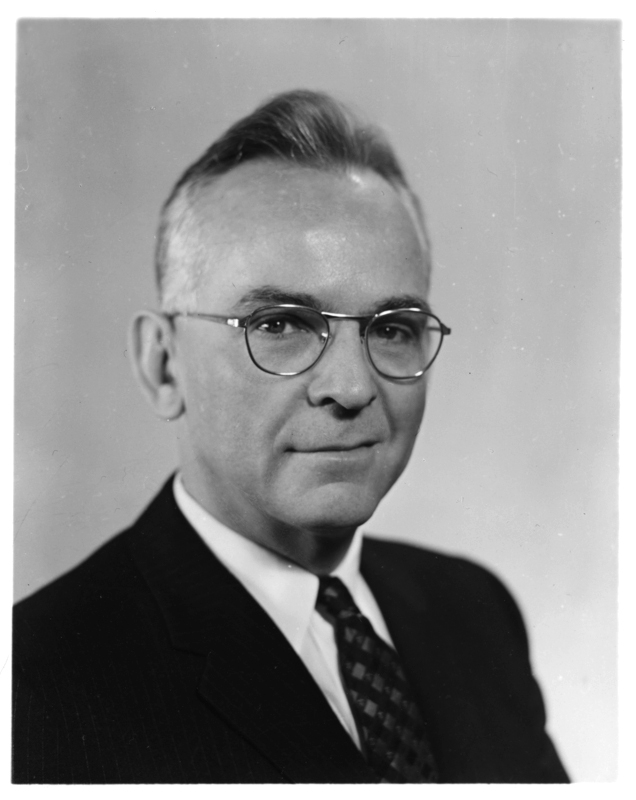

Ironically, the EO program’s first chairperson, Leland DeVinney, did not think it should. He argued that Foundation should not invest in the poorly resourced HBCUs since most were, in his estimation, inferior to top-tier universities and would take years to improve.

“You’re not willing to keep at it with black colleges for three generations,” he once told another RF officer, “and that’s what it takes. Therefore, don’t do it.”Romney, 46-47.

Instead, DeVinney wanted to open doors for high-achieving African American students to attend white colleges. Gradually, he reasoned, this process would integrate higher education, increase the flow of African Americans into professional leadership positions, and decrease the number of students attending HBCUs, rendering them a relic of Jim Crow segregation.

Others disagreed, arguing that HBCUs still played a vital role in educating African American students. As RF President George Harrar recalled:

There was clear-cut racial discrimination throughout the school system, [but] we couldn’t integrate overnight. You can’t have instant change like instant coffee.Elizabeth Romney, “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Equal Opportunity Program: A Short History,” 47, Richard Lyman papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Pressure from the Kennedy Administration

However, the RF soon shelved this nuanced debate in the face of persistent lobbying from President Kennedy, who likely viewed the UNCF campaign as an opportunity to signal his support for civil rights at a time when more Americans had come to expect federal leadership on the issue.

The first letter came in May 1963, a request sent to John D. Rockefeller 3rd, chair of the RF board, asking the RF to contribute $5 million to the Fund and referencing a recent $15 million pledge from the Ford Foundation.

The pressure applied by this letter was significant – the sitting president was fundraising for the nation’s preeminent organization of HBCUs, which had received a significant commitment from a leading philanthropic institution.

RF officers initially turned down the president’s request, citing the Foundation’s opposition to supporting segregated institutions.“Excerpt from Minutes of Officers’ Docket Conference,” June 4, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

This is a rather tough one to handle and feeling our way a bit is for the best.

John D. Rockefeller 3rd to RF President George Harrar, July 15, 1963.

Nevertheless, the officers and trustees understood the importance of Kennedy’s letter. While denying the initial inquiry, the Board pledged to examine how “the Foundation might contribute promptly and effectively to educational programs designed to train Negro leadership.”

For the first time, the RF had made a commitment to explore a new equal opportunity program.Summary of Executive Committee Discussion, June 21, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

RF leaders left the door open for future action throughout the summer. George Harrar refused to decline new UNCF requests in writing, thus allowing the RF to offer support if and when it created the new EO program.George Harrar to John D. Rockefeller 3rd, July 15, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

John D. Rockefeller 3rd agreed with this decision, noting, “It is wiser to not send a declination at this time to the UNCF people. This is a rather rough one to handle and feeling our way a bit is for the best.”John D. Rockefeller 3rd to George Harrar, July 16, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Creating the EO Program

The following month, President Kennedy again prevailed upon the RF to support the UNCF drive. In an August 6 letter to Harrar, the president noted he had enlisted Charles G. Mortimor, Chairman of the General Foods Corporation, to lead the UNCF’s fundraising campaign and that a committee had been gathered of prominent business, foundation, and education executives, including the heads of the Ford Foundation, the Commonwealth Fund, the Carnegie Corporation, the Gillette Company, Goldman and Sachs, and Harvard University. On September 12, the committee planned to meet at the White House to discuss the UNCF fundraising drive.John F. Kennedy to George Harrar, August 6, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center; List of Attendees to September 12 Meeting, Rockefeller Foundation records, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

In response, Harrar sought to expedite the creation of the RF’s EO program. The next day, he established an interdisciplinary committee of RF division heads to examine how the Foundation might support black educational opportunity. The committee continued to oppose contributing to the UNCF, but promised to outline an alternative program idea.Flora Rhind, “Negro Education,” August 7, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.29, Series 900, Program and Policy – Equal Opportunity, 1959-1973, Rockefeller Archive Center.

By this time, the RF had also started receiving additional grant requests from other educational institutions beyond the UNCF. “It would be unfortunate,” the committee noted, “if a number of good but miscellaneous unrelated projects were supported at this time.” Typically, the RF was most concerned with avoiding “scatteration,” its term for the frittering away of funds without a cohesive plan.Flora Rhind, “Meeting of Exploratory Committee re Program in Negro Education and Related Matters,” August 13, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, RG 1.29, Series 900, Program and Policy – Equal Opportunity, 1959-1973, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Final Decisions

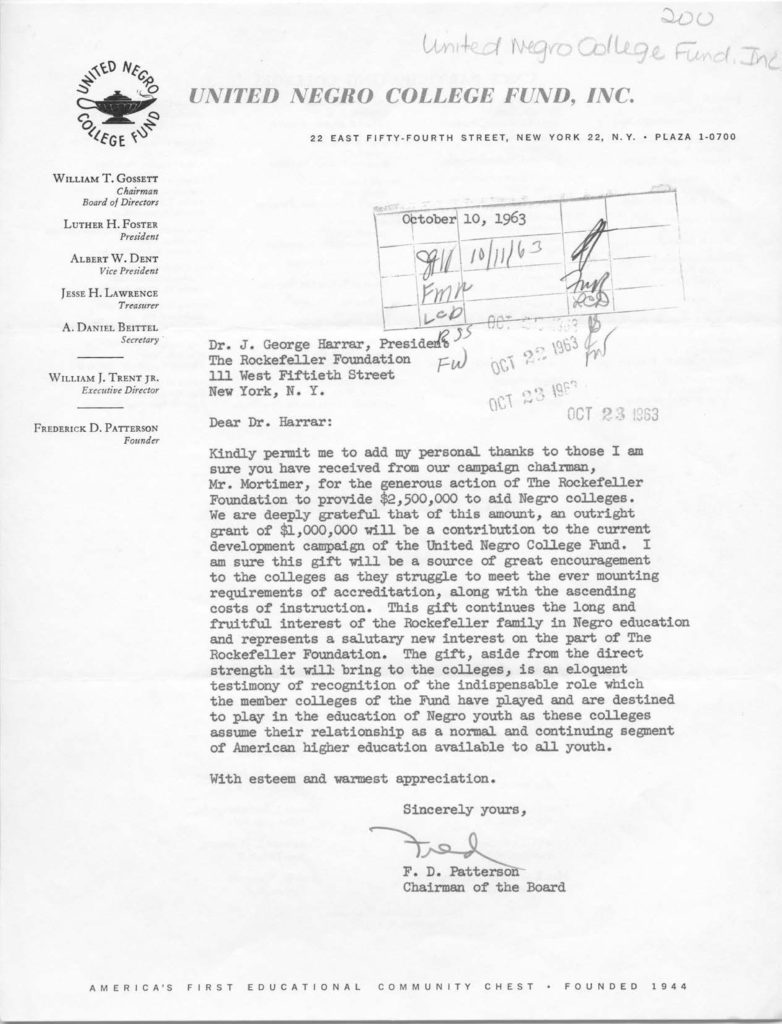

The RF Board simultaneously approved the UNCF grant and created the new EO program on September 20, 1963.

Noting that its consultations with African American leaders had illuminated the continued importance of HBCUs to black education, the Foundation appropriated $2.5 million to the UNCF over the next three years – $1 million as a general grant to the organization and another $1.5 million to a handful of colleges that were UNCF members.UNCF Grant, September 20, 1963, Rockefeller Foundation records, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The new EO program, for its part, sidestepped internal debates about the modern-day relevance of HBCUs. Instead, Toward Equal Opportunity For All embraced a mission that aimed to provide “disadvantaged citizens with better educational opportunities,” writ large.

The phrasing was important. By being non-specific, the Foundation remained open to engaging with different types of educational institutions, whether HBCUs or non-HBCUs, colleges or pre-college institutions.

It was perhaps inevitable that the RF would eventually launch this equal opportunity program. But the UNCF grant request, not to mention the political pressure that followed, accelerated and perhaps even kickstarted the process. What RF leaders had initially viewed as an anomalous funding request helped spark an entirely new program area devoted to African American education. In the coming years, the new EO program would expand its programming, supporting new experiments in community schooling, leadership development in the inner-city, youth employment demonstrations, and more for an increasingly diverse range of minority groups. In short order, the Foundation came to see these programs as crucial to its efforts to respond to some of the pressing issues of the day.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

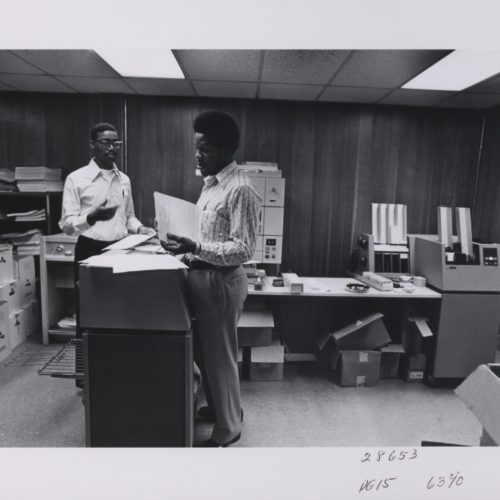

- “Baltimore – Education – Interns – Principals,” 1969-1970. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, General (No Program), Subseries 200.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “New York Urban League – Street Academy Program,” 1968. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, General (No Program), Subseries 200.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “United Negro College Fund, Inc.,” 1962-1966, 1972. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, General (No Program), Subseries 200.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

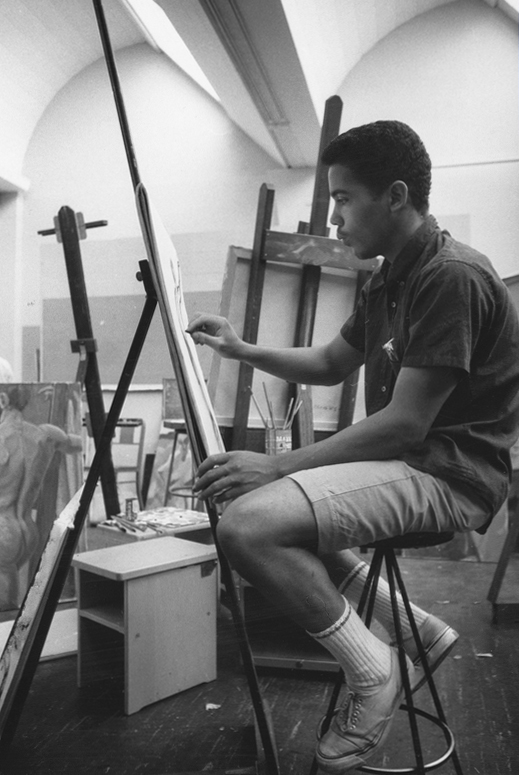

- “Dartmouth College – Summer Program,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, United States, Series 200, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Occidental College – Equal Opportunity Program,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, California, Series 205, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Wesleyan University – Summer School,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Connecticut, Series 208, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.

Related

The Rockefeller Foundation Confronts School Inequality

A college prep program increased admissions rates for at-risk students, but it also raised larger questions about systemic inequality.

Can Data Drive Social Change? Tackling School Segregation with Numbers

In the years before Brown v. Board, a philanthropic fund hoped research and data would turn the tide on attitudes toward segregation.

Photo Essay: Supporting Minority Enterprise in the late 1960s

In 1968, the Ford Foundation began to make social investments using a new tool borrowed from the for-profit world, the Program-Related Investment.

Supporting Economic Justice? The Ford Foundation’s 1968 Experiment in Program Related Investments

How the largest US foundation began supporting market-based projects in the late 1960s.