Support for cultural projects did not come early or easily to the Rockefeller Foundation (RF). Science and health dominated funding priorities. The arts and humanities were absent at the start of the Foundation and frequently struggled to find a secure place within it.

Something of Beauty

In 1924 program officer Edwin Embree asked plaintively,

Of what good is it to keep people alive and healthy if their lives are not to be touched increasingly with something of beauty?

Edwin EmbreeEdwin Embree, Gedney Farm Conference, January 18-19, 1924, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), Series 900, Box 22, Folder 165.

He outlined an impressive set of funding possibilities, from arts training programs to international cultural exchange. But a formal program did not take shape until after the Foundation’s 1928 reorganization when it inherited the humanities program of the General Education Board.

While the humanities acquired a formal home within the Foundation, their place was still not secure. Alan Gregg, Director for the Medical Sciences, questioned the Rockefeller Foundation commitment to the humanities when so much work remained to be done in science and health, fields in which the RF was already well-versed and internationally respected. In a 1930 memorandum, Gregg argued that “in the present world, with the exception of parts of the United States, I would not consider the greater needs of mankind to be aesthetic and cultural.”Memorandum by Alan Gregg, October 27, 1930, RAC, RG 3, Series 911, Box 1, Folder 1. He went on to question whether the Rockefeller Foundation was qualified to critique or assist the cultural development of other nations and indeed whether that type of help would even be welcome. Nevertheless, the 1930s witnessed Foundation staff, under humanities director David Stevens, begin to support the arts through funding to regional theater in the US and Canada and scholarly studies of US regional culture.

While the programmatic structure has been fluid, the strategies diverse, and the usefulness of culture much debated, the Foundation has made numerous contributions to drama, dance, music and literature. Sometimes the commitment swelled within a broad national context. In the mid-1960s, President George Harrar described the RF’s work in the US as part of a national movement toward “cultural democracy.” It was an era that saw the creation of the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, the proliferation of performing arts institutions, and the growth of area studies and American studies within higher education. This national cultural efflorescence continued to animate the Foundation’s cultural programs in the 1970’s, especially its fellowship programs for individual artists and scholars.

In 1962, the humanities program was consolidated with the social sciences division, the first of many shuffles and reconfigurations of the Foundation’s cultural programs. The arts and humanities were separated, merged, separated, and merged again until the arts and humanities programs were terminated in 1999 and replaced by the thematic program “Creativity and Culture”. This theme continued until 2005, when it too was phased out.

Drama

The Rockefeller Foundation has consistently sponsored drama programs throughout its support of the humanities. Over many decades RF work has advanced the regional theater movement, improved university programs in drama, and supported emerging playwrights. Interest in drama took shape in the 1930s when RF trustees and humanities director David Stevens (1932-49) wanted to broaden popular engagement with the arts and to support distinctively American regional cultures. Drama proved an ideal medium to tell local stories in ways that would be appealing to large audiences.

Living Drama

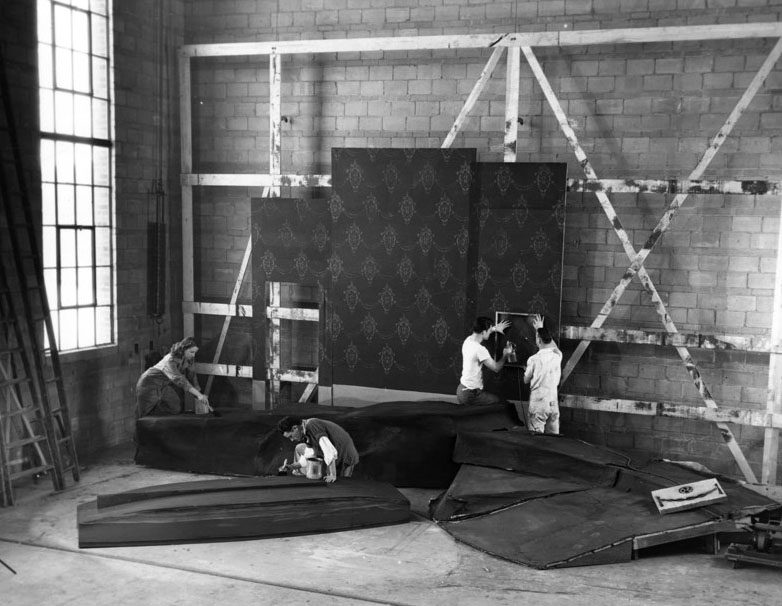

Beginning in 1933, as part of an initiative to preserve and interpret American cultural traditions and to promote appreciation of the nation’s heritage, the Rockefeller Foundation gave its first grants in drama to outstanding community theaters and university drama programs. Throughout the 1930s grants were given to institutions that included the University of Iowa, Yale University and The Cleveland Play House Foundation.

Among the first and most consistently supported grantees was the Carolina Playmakers at the University of North Carolina (UNC). The Carolina Playmakers, comprised of UNC students led by faculty member Frederick Koch, had already written and performed plays based on regional folk tales and the lived experiences of the students and their families. They had taken them to audiences throughout North Carolina and the southeastern United States, performing in towns where no permanent theaters existed. Inspired by Irish writers and poets such as Yeats and Synge, Koch was an American pioneer in the field of folk drama. The Rockefeller Foundation was drawn to his work because

[T]he plays written and produced under [Frederick Koch’s] direction deal predominantly with people and situations of which his students have direct knowledge, either by their own experiences or from living tradition. This relation of the author to his material gives the plays a value as authentic records of American life.

Rockefeller Foundation Grant Report, 1933Rockefeller Foundation appropriation to University of North Carolina, December 13, 1933, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 1.1, Series 236R, Box 7, Folder 80.

The program at UNC appealed to Rockefeller Foundation officers not only for its secure academic grounding but also because of its regional focus and its demonstrable audience appeal. The Rockefeller Foundation appropriated funds in 1933 to aid UNC programs in playwriting and experimental production and to extend the Playmakers’ reach into high schools, community centers and festivals across North Carolina. The relationship between the RF and Koch’s drama program continued for a decade. Major achievements included the 1937 production of The Lost Colony, written by former Koch student and UNC instructor Paul Green. That play traversed the state and was seen by an estimated audience of 100,000.

Along with its support for university drama programs and community theaters, the Rockefeller Foundation revived the National Theatre Conference, which had been established to raise the level of amateur drama and to promote theater education. The Foundation drew leading playwrights and directors together through the Conference and used their expertise to administer fellowships and other theater training programs. The appeal of theater to the humanities division was well expressed in the National Theatre Conference’s 1935 proposal: “No form of leisure time activity presents wider or richer possibilities than the theatre. A synthesis of all the arts, it offers to every individual some form of active or passive participation.”Draft of request for funding from National Theatre Conference to David H. Stevens, April 9, 1935, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 200R, Box 255, Folder 3042.

While RF-initiated work at UNC, Iowa, and Yale continued, other universities benefitted from RF grants in the late 1930s and 1940s, including funding for a new drama building at Stanford and for strengthened drama departments at Smith College, the University of Saskatchewan, the Stevens Institute of Technology, the University of Wisconsin, and many other schools.

No form of leisure time activity presents wider or richer possibilities than the theatre.

National Theatre Conference Proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation, 1935

The Rockefeller Foundation’s work in drama was not exclusively university and community-based. The Foundation also supported professional theaters with notable grants in the 1950s to Shakespearean festivals, including Connecticut’s American Shakespeare Festival and the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Canada.

Playwrights and Plays

With the consolidation of the Foundation’s programs in the humanities and social sciences in 1962 and the retirement of Charles B. Fahs as director of humanities that same year, every field of foundation activity saw strategic shifts in focus. In 1964 work in the arts was separated from work in the humanities. Norman Lloyd, formerly the dean of Oberlin’s Conservatory of Music, directed the program from 1965 to 1970. Drama, along with music and literature, remained the key disciplines receiving Rockefeller Foundation funding. “Cultural development” was the driving theme, an acknowledgement that while artistic creativity was thriving and audiences were more robust than ever, the financial support system for artists and artistic works was fragile. As the Foundation’s 1964 Annual Report complained:

Government support of cultural activities is virtually non-existent; of the estimated $850 million a year appropriated by foundations, perhaps only 1 per cent finds its way to the performing arts and other cultural projects.

Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1964The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report 1964 (New York, The Rockefeller Foundation, 1964) 72.

The Rockefeller Foundation, which had played a key role in the decentralization of American theater and built a strong base for theater in universities, now turned to breaking down the barriers between professional and educational theater. The Foundation helped Stanford plan for a professional theater company on campus, and it helped the University of Minnesota collaborate with the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis.

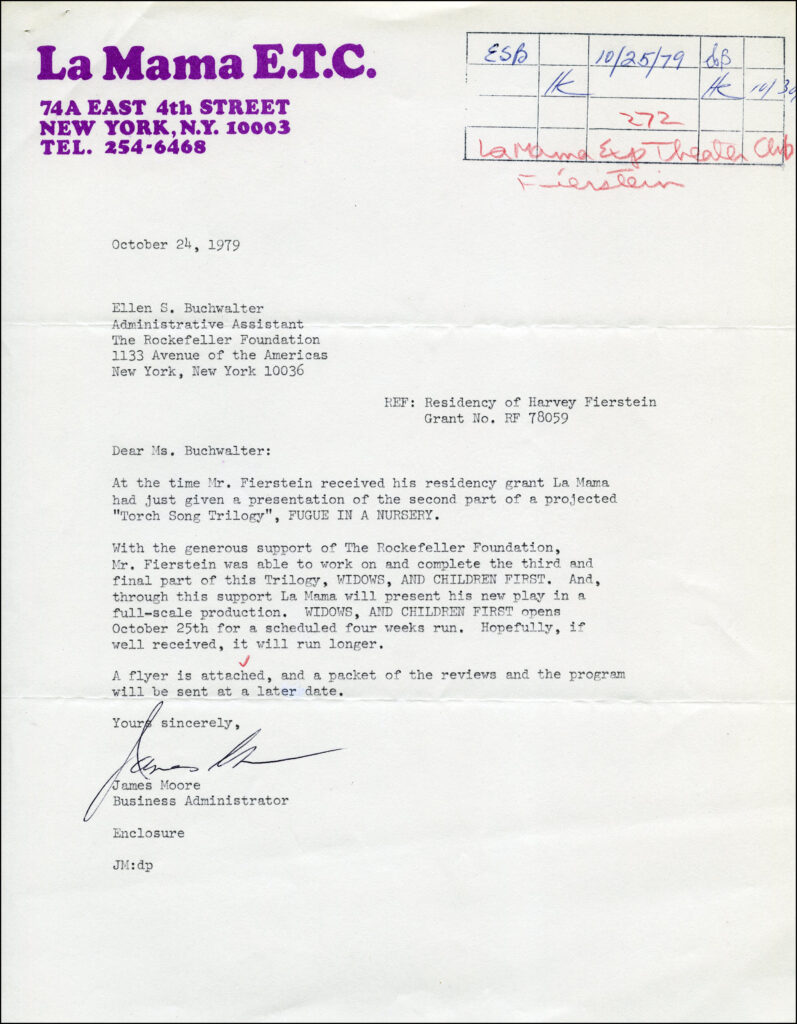

The Foundation also assisted emerging playwrights, including a financially strapped Sam Shepard, then in his early twenties. Despite his self-described doubts about whether he would be a “good investment” for the Foundation, he was given $5,500, allowing him to write full-time.Letter from Sam Shepard to Robert W. Crawford, September 22, 1965, RAC, Series 200R, Box 417, Folder 3594. During that year Shepard wrote the Obie Award winning play La Turista. In 1970 RF support for playwrights was provided through the Fellowships for American Playwrights and Playwrights-in-Residence Program. This program joined playwrights in mid-career with regional theaters across the United States for six-week residencies. The program provided a pressure-free space for creativity since there was no expectation that a play had to be produced by the time the residency ended. Notable grantees included Sam Shepard, who partnered with San Francisco’s Magic Theater, and Harvey Fierstein, who was nominated and hosted by Ellen Stewart of New York City’s La Mama Experimental Theater Club. The program had dual (and dramatic) results, supporting talented writers and also helping to create a thriving network of professional off-Broadway theaters.

This program persisted into the 1980s as the “Fellowships for American Playwrights”. Other drama grants in the 1980s included support to the Lincoln Center Theater in New York City, and funding to develop international drama at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). The establishment of the Festival Fund helped theater to take root throughout the United States, often in places that rarely saw the work of living artists, while the Fund for U.S. Artists in International Festivals and Exhibitions (partnering with the NEA, the Department of State and the Pew Trusts) exported American theater around the world.

As theater changed to expand into multidisciplinary initiatives and new types of storytelling, as well as making use of new technology, the Foundation broadened its support. In 1999 the Foundation was approached by Moisés Kaufman of the Tectonic Theater Project as he and fellow theater members worked to create a play inspired by the 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard and based on the oral histories of the people of Laramie, Wyoming. The Rockefeller Foundation contributed $40,000 to the development of The Laramie Project. The play opened in Denver before an off-Broadway run in NYC. Since 2000, The Laramie Project has been performed in numerous cities, and went on to be made into an HBO film of the same title.

Music

The Rockefeller Foundation’s most extensive commitment to music spanned slightly more than two decades. It began with programs to commission new works for the Louisville Symphony Orchestra in the 1950s, continued with support for individual composers, and reached its high point in 1976 with a project to distribute the 100-disc Recorded Anthology of American Music to schools, libraries and United States Information Service (USIS) cultural centers around the world.

Prelude

The Rockefeller Foundation did not begin to think seriously about how it might expand its humanities funding to include a program in music until after World War II. But earlier grants signaled an emerging and opportunistic interest on the part of the Foundation in funding music-related programs. The Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky had begun its Berkshire Festival concerts in 1938. Only a year later the Foundation stepped in with a $60,000 grant to help the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood get off the ground; it opened in 1940 as a training ground for musicians and conductors. While the appropriation was considered to be “out-of-program,” Jerome Greene, a major proponent of the Berkshire grant, wrote a decade later:

… I always attached importance to an occasional opportunity to do something unrelated to program if it offered a chance to support a new and sound enterprise at a moment of great strategic significance … Adaption to newly discovered needs, with the money to meet them, if they were important enough, was always claimed as one of the advantages of a great and sufficiently fluid fund.

Jerome Greene, 1950Letter from Jerome Greene to Chester I. Barnard, February 9, 1950, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 1.1, Series 200R, Box 212, Folder 2537.

Another music project also had continuing resonance, for better and for worse. Hans Eisler, a German composer working at the New School for Social Research, was given a grant in 1940 to study music composition for film. His work yielded both new scores for film and theoretical writings about the relationship between music and moving images. In the 1950s, however, the funding for Eisler was among the Rockefeller Foundation grants questioned by the congressional committees investigating foundation relationships with subversive organizations and individuals when Eisler faced accusations of being a Soviet agent and was placed on a Hollywood blacklist.

While the Foundation had supported the fields of drama and film since the 1930s, only in 1948 did talk begin in earnest about an arts program that would include music. The Foundation brought together musical luminaries including Quincy Porter, Virgil Thomson and Otto Luening to discuss possible avenues for RF involvement in music projects. The group proposed fellowship programs to nurture young musicians and conductors and funding for the publication of musical recordings and scores.

Placing a Bet in Louisville

In 1953, after several years of planning, the first grant in a more expansive music program was awarded. The Louisville Philharmonic Society received $400,000 to expand its commissioning and recording programs. Since 1948 the Louisville Orchestra had been commissioning new works by prominent composers, among them Paul Hindemith, Darius Milhaud and Virgil Thomson. The orchestra aspired to perform a new work for each week of its forty-six week season. The goal was to expand the market for new music through repeat performances, broadcasts and recordings.

The decision to award the initial grant to the Louisville Symphony Orchestra was heavily debated by Rockefeller Foundation staff. John Marshall made several visits to Louisville to meet with its mayor, Charles Farnsley, who enthusiastically sold the project, noting that any comparable endeavor would be lost on a big city and that the choice of Louisville would garner attention among outsiders surprised that a city of that size would take on such an initiative. Considering the proposal, Marshall wrote following his visit with Farnsley in 1952:

If the scheme seems, as it must at first, audacious, this may turn out to be its most engaging quality. Certainly, there is an opportunity to do something of this sort in Louisville with good reason to believe that in the present context there it could have as much if not more success than in some other location.

John Marshall, 1952Interview notes by John Marshall, October 7, 1952, RAC, RG 1.2, Series 200R, Box 372, Folder 3239.

The project in Louisville reveals an unstated aim of the Rockefeller Foundation’s cultural programs in the 1950s and 1960s. With Cold War cultural competition in mind, the Foundation supported the arts to demonstrate American ideals and promote the potential of American culture abroad.

New Directors and Directions

Following the Louisville grant, the Rockefeller Foundation entered an active period of supporting American music and musicians. Scholarships were funded at Tanglewood; the American Symphony Orchestra League received money to help train conductors; audience development projects were supported through Young Audiences, an organization dedicated to bringing concerts into elementary schools; small regional symphonies were supported; an electronic music program at Columbia University received funding in 1958; and even more substantial funds flowed into new music projects and composer residencies beginning in the mid-1960s.

Support for music continued after 1964 in a new Arts Division under the directorship of Norman Lloyd. For the first time, though only briefly, the arts were separated from the humanities. Lloyd’s program supported composers, including a special grant for African American composers, and funded eleven orchestras to perform and record little-known works by American composers. Howard Klein, a Juilliard-trained composer and a former music critic, succeeded Lloyd. He continued to support new music, especially through the International American Music Competition at Carnegie Hall. Seeing how difficult it was for individuals to receive support, Klein persisted in making grants to talented artists in every field and ultimately began to work with intermediaries such as Meet the Composer to manage the selection of grant recipients.

Coda and Decrescendo

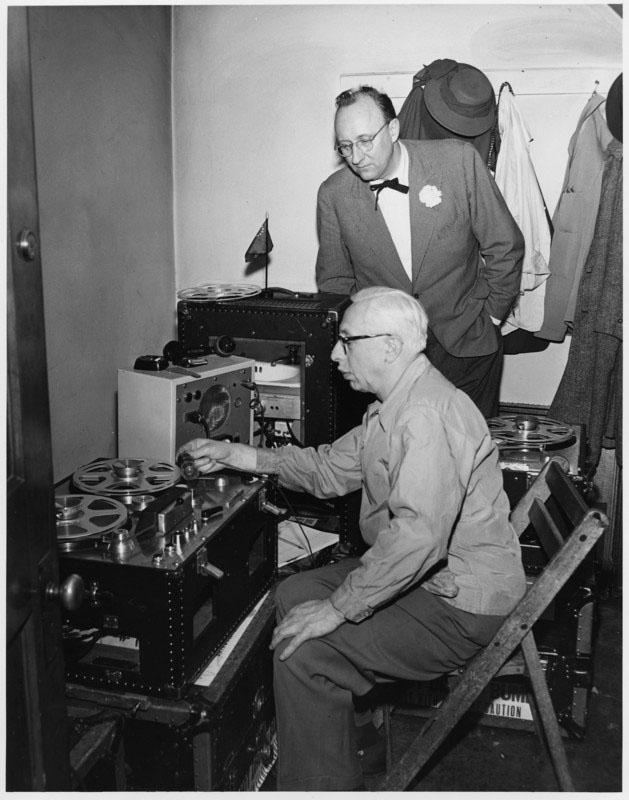

The Rockefeller Foundation’s support for music culminated in its Recorded Anthology of American Music, a project planned for the American bicentennial in 1976 and representing the Foundation’s largest-ever financial commitment to music. An independent nonprofit recording company, New World Records, was established to produce, manufacture and distribute a 100-record survey of the nation’s music. With an investment of some $4 million, the record sets were distributed to music schools, libraries, radio stations and USIS centers around the world.

In the early 1980s, the Arts and Humanities were re-combined in a single program. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Rockefeller Foundation implemented international and intercultural programs intended to reinforce the Foundation’s overall global strategies. Music organizations and composers were essential in the new program that included funding for artists at international festivals and exhibitions.

The heady quarter century that began with grants to advance American music at the Louisville Symphony ended with offerings of American music world-wide.

Dance

The Rockefeller Foundation has not consistently supported dance programs, often doing so in conjunction with funding other artistic disciplines. While its early support helped such organizations as New York City Center and the San Francisco Ballet, its later efforts focused primarily on contemporary choreographers and their companies. In keeping with its ambitions to foster intercultural understanding, the Foundation underwrote tours and festival participation for dance companies until the formal arts program came to an end in the late 1990s.

First Steps

The first grants providing significant help for dance came in the early 1950s at the same time that the Foundation was expanding its music initiatives. In 1953 a $200,000 appropriation to the City Center of Music and Dance in New York, then only a decade old and home to both the New York City Opera and the New York City Ballet (NYCB), helped both resident companies and a short-lived theater company. The companies had attained an impressive level of artistic success, and NYCB had already toured nationally and internationally. With ticket prices held to a minimum, City Center was drawing more than 500,000 persons annually to its performances. The companies’ emphasis on new works appealed to RF staff members, and City Center’s grant was intended to create new scores, choreography, costumes and sets for both opera and ballet.

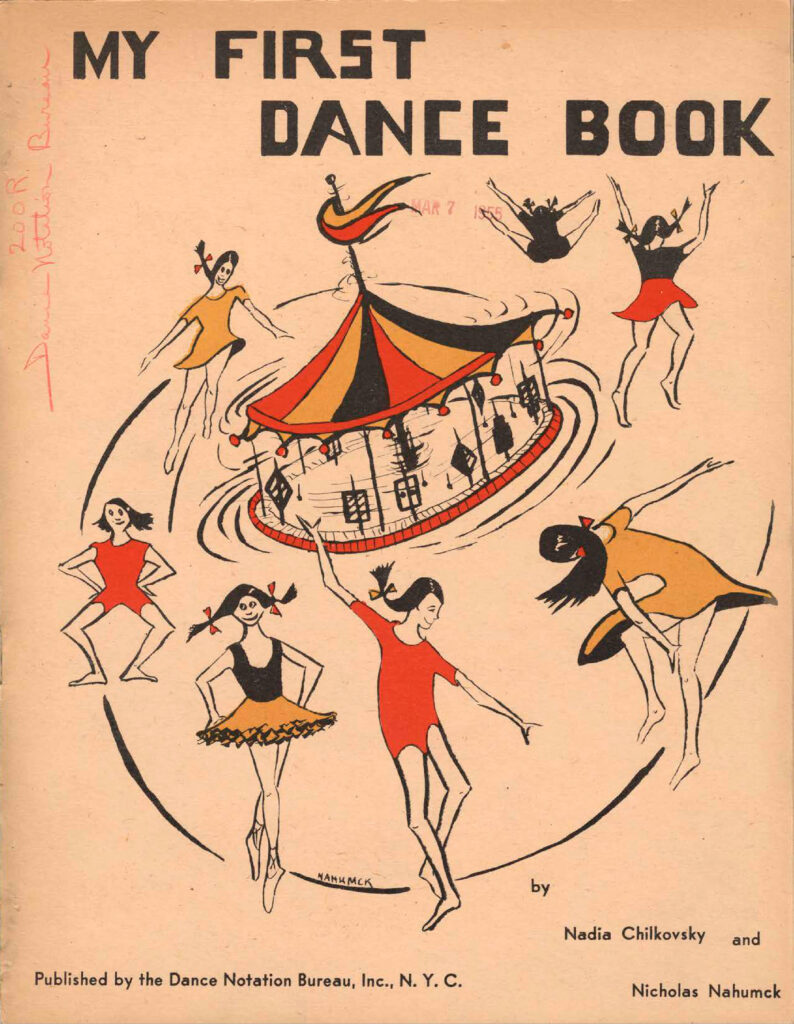

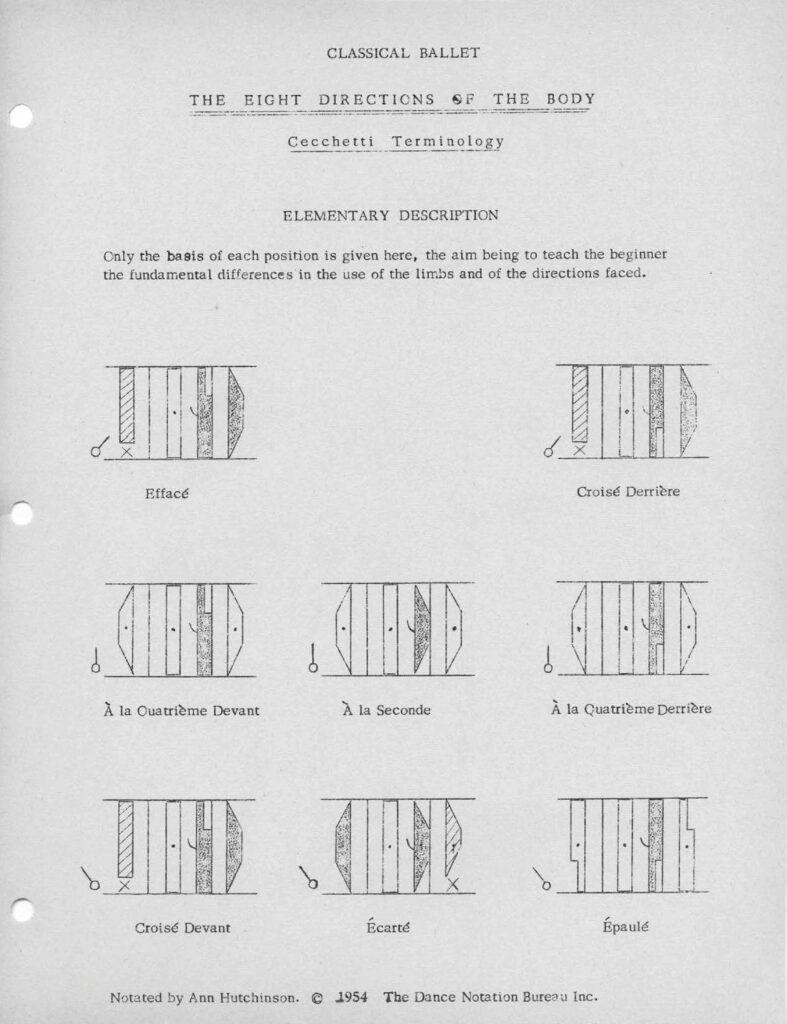

Modern dance flourished in mid-century America. RF hoped to preserve the accomplishments of this ephemeral art form. In 1955 a grant to Connecticut College’s Summer School and Festival of the Dance helped the college to film, publish, archive and disseminate choreographic works to other organizations. The college and the Dance Notation Bureau also received funding to develop Labanotation, a graphical system for noting movement that had been developed by Rudolf Laban in the 1920s and was later adapted to capture dance by RF grantee Ann Hutchinson Guest. The textbooks she wrote have proved central to the study of dance.

Companies and Choreographers

The RF ceded center stage in dance to the Ford Foundation’s much larger arts program, which expanded rapidly in the late 1950s and 1960s. While RF had supported new choreographic works at the San Francisco Ballet and the National Ballet of Canada, it was Ford that transformed major regional ballet companies into nationally prominent organizations. Rockefeller concentrated its more limited resources on supporting contemporary dance companies, including Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Alvin Ailey, Robert Joffrey, and, at the Bellagio Center, Bill T. Jones, among others.

In the 1980s, the RF, partnering with the National Endowment for the Arts and the Exxon Corporation, implemented the National Choreography Project, placing contemporary choreographers in residencies with classic dance companies to increase repertory and experimentation. The Foundation frequently funded national and international tours, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, to encourage international cultural understanding between the United States and developing countries. Dance Theater Workshop’s Suitcase Fund was among these programs funded by RF.

Although the RF’s formal arts and humanities programs came to an end in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the Foundation continued to provide funding for artistic life in its home city. The NYC Cultural Innovation Fund, for example, supported artists and institutions working to enhance the creative sector in New York, echoing the assistance first rendered sixty years ago to City Center.

Related

American Choreographers: Funding the Creative Process

Grant makers and grantees cooperated to craft a unique program in dance.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “University of North Carolina – Drama,” 1933-1938. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, North Carolina, Series 236, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 236.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of North Carolina – Drama – Supplementary Material,” 1935-1944. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, North Carolina, Series 236, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 236.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of Iowa – Drama – Reports,” 1934. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, Iowa, Series 218, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 218.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Theatre Conference,” 1933-1940. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Stratford Shakespearean Festival,” 1952 March – 1957 December. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, Canada, Series 427, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 427.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy – Music,” 1948-1958. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 1, Humanities, Series 911, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Boston Symphony Orchestra – Berkshire Music Center,” 1942-1950. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Louisville Philharmonic Society – (Contemporary Music Commissions and Recordings),” 1951-1955 August. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Philharmonic – Symphony Society of New York – (Modern Dance Performance) – (John Cage, Merce Cunningham Dance Troupe),” 1965. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Connecticut College – Dance – (Summer School),” 1950, 1952-1957. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Dance Notation Bureau – (General Support),” 1951-1964, 1978. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Dance Notation Bureau – Reports,” 1958. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Ballet Guild of Canada,” 1954-1961, 1963-1964. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, Canada, Series 427, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 427.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “San Francisco Ballet Guild,” 1955. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.2, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Program and Policy,” 1962-1974 February. Rockefeller Foundation records, Administration, Program and Policy, Record Group 3, Subgroup 3.2, Arts, Series 925, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Ballet of Canada,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Canada, Series 427, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 427.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Foundation for American Dance – Joffrey Ballet,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Louisville Philharmonic Society,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “National Theater Conference,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, United States, Series 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of Iowa – Drama Arts Building,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Iowa, Series 218, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 218.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- 200, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 200.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of Iowa – University Theater,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Iowa, Series 218, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 218.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “University of North Carolina – Drama,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, North Carolina, Series 236, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 236.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Stratford Shakespeare Festival,” 1954, 1955, 1962. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Canada, Series 427, Humanities and Arts, Subseries 427.R, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.