The history of America’s national and state parks includes a long-lasting engagement with more than three generations of the Rockefeller family. While wealth has enabled the family to acquire plenty of land for their own enjoyment, various family members have also donated their own land for public use or purchased tracts of wilderness with the intention, from the beginning, of donating them. The nation’s parks, perhaps our most remarkable public resource, have a history of private largesse.

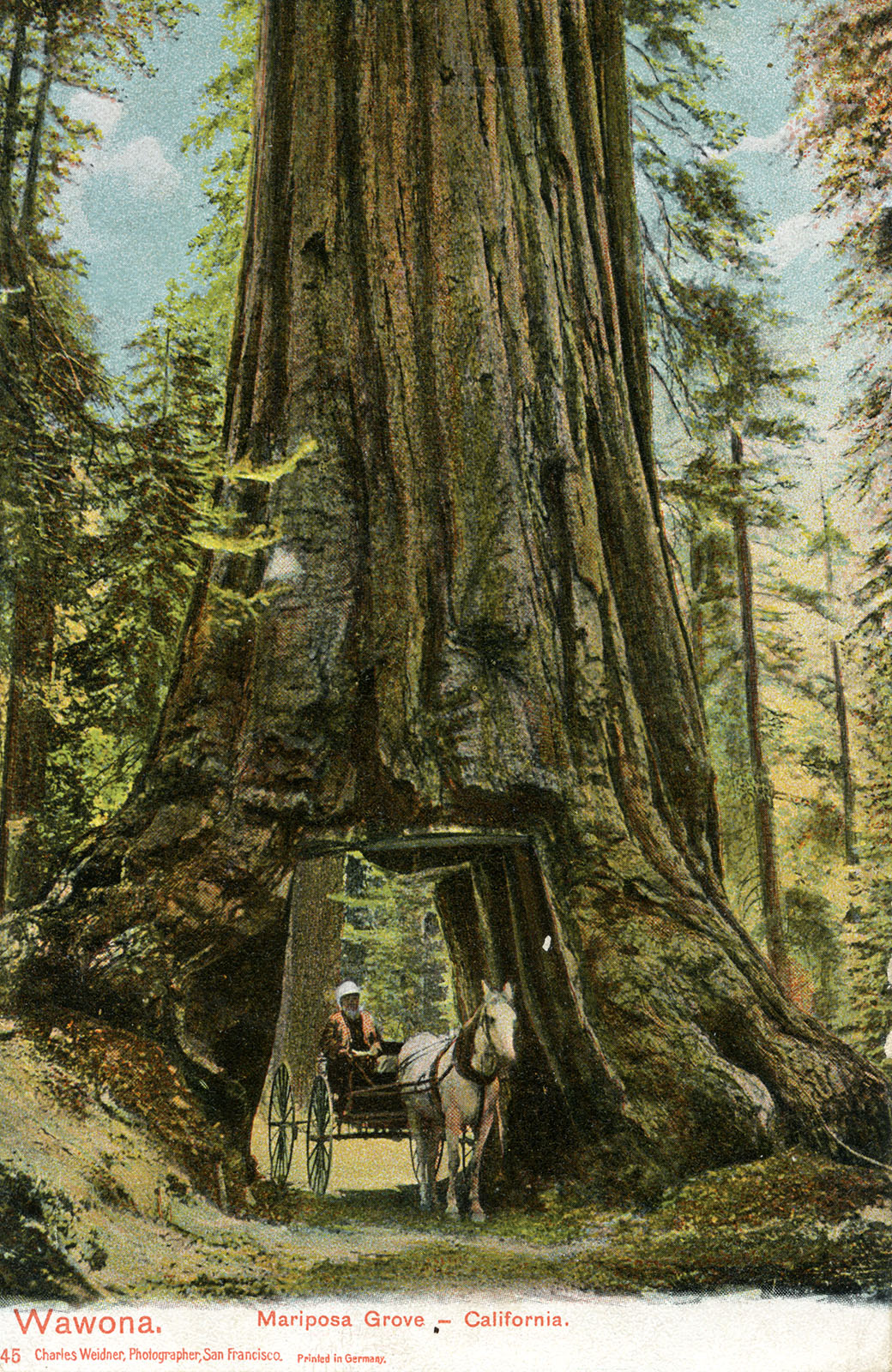

The roots of the national park system precede the Rockefellers, going back to Abraham Lincoln’s decision in 1864 to grant Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove to the State of California, permitting the state to own it on behalf of the public and empowering the US Army to protect it. Yosemite was not the first national park — in 1872, Wyoming’s Yellowstone took that title. Then, in 1890, Yosemite joined it, becoming the nation’s third national park (Sequoia was the second). But it would not be until 1916 that Congress acted to create the National Park Service.

John D. Rockefeller Reshapes the World

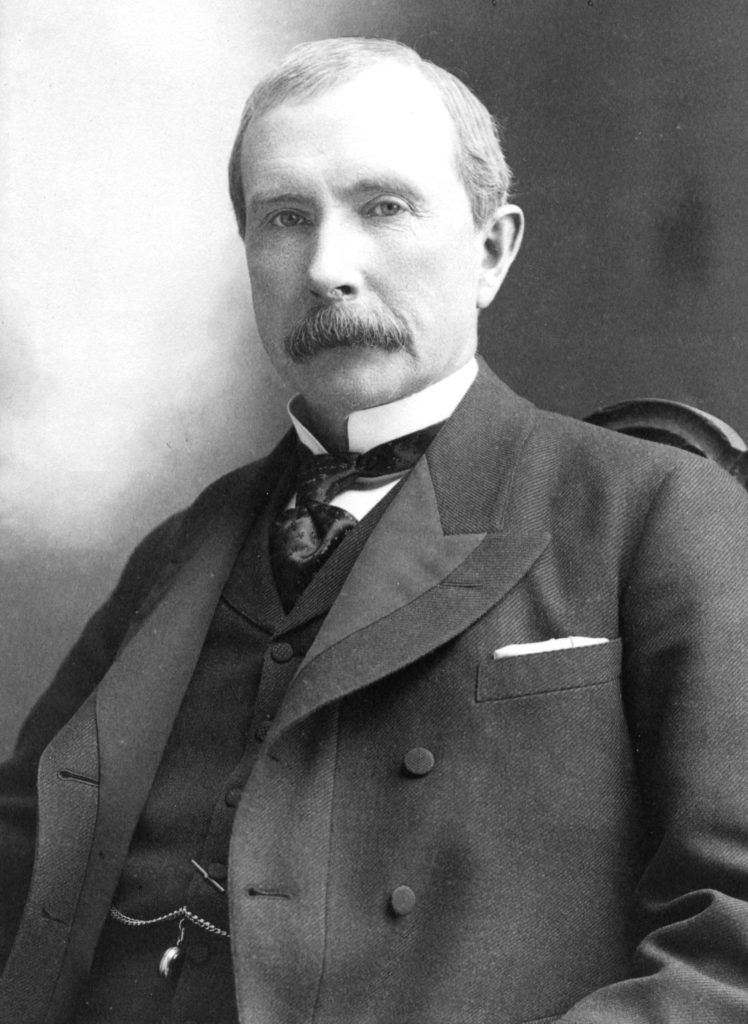

John D. Rockefeller was born in 1839, twenty-five years before Lincoln granted Yosemite to California. When California acquired Yosemite in 1864, the young Rockefeller had just entered the emerging oil business. By the time Yosemite became a national park in 1890, he was on the cusp of retirement from the Standard Oil Company, the unprecedented corporation he founded, and well on his way to becoming America’s first billionaire.

In the relatively short timespan between Lincoln’s gift and the establishment of the first handful of national parks, Rockefeller not only made a personal fortune, he transformed American business practices forever. Standard Oil (along with several of its contemporaries) introduced a style of unfettered industrial capitalism that concentrated extreme wealth in the hands of a few, threatened natural resources with extractive industries, and reshaped the American landscape with new infrastructure and development enabled and driven by these industries.

It is slightly ironic, then, that Rockefeller would produce a family tree brimming with conservationists.

Growing up in upstate New York, Rockefeller first experienced the natural landscape among the fields and forests near the town of Richford. Later, his family moved to a larger home in the Finger Lakes region, set on 92 acres including a gentle hillside sweeping down to the brilliant blue shimmer of Owasco Lake.

Rockefeller’s youngest child and only son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was born in 1874 at the height of Standard Oil’s dominance, and had a more urban and suburban upbringing than his father’s. At the family’s home in the Cleveland, Ohio suburb of Forest Hill, the natural beauty of the rolling landscape captivated both father and son. According to JDR, Jr., his “passionate awareness of the outdoor world” developed at Forest Hill.

Father and Son

Together, the two Rockefellers marked out carriage trails, designed dams to create ponds and lakes, built stone bridges, and planted trees. They thoroughly enjoyed cultivating and manipulating the landscape around them. This urge to enhance the beauty of the natural environment through careful staging would remain with the younger Rockefeller all his life, directly contributing to his engagement with the national parks.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. left school several times throughout his youth to recover from illnesses or periods of stress. As a teenager, he spent time chopping wood and wandering the Forest Hill estate on his own. He later recalled, “I think perhaps I have always had an eye for nature. I remember as a boy loving sunsets…I remember the fairy forms of the trees when they shed their leaves. I remember what the sycamore trees looked like, and the maple trees. Every time I ride through the woods today, the smell of the trees — particularly when a branch has just been cut and the sap is running — takes me back to my early impressions in the woods.”John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to Raymond B. Fosdick, as quoted in Raymond B. Fosdick, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.: A Portrait. Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1956, p.302.

Making a Home in the Hudson Valley

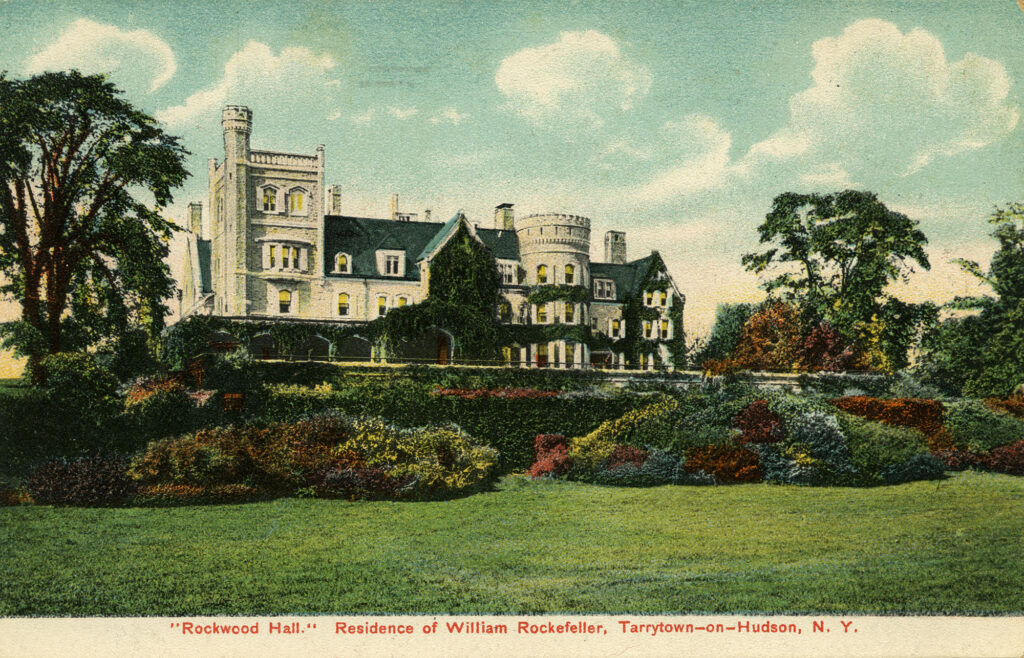

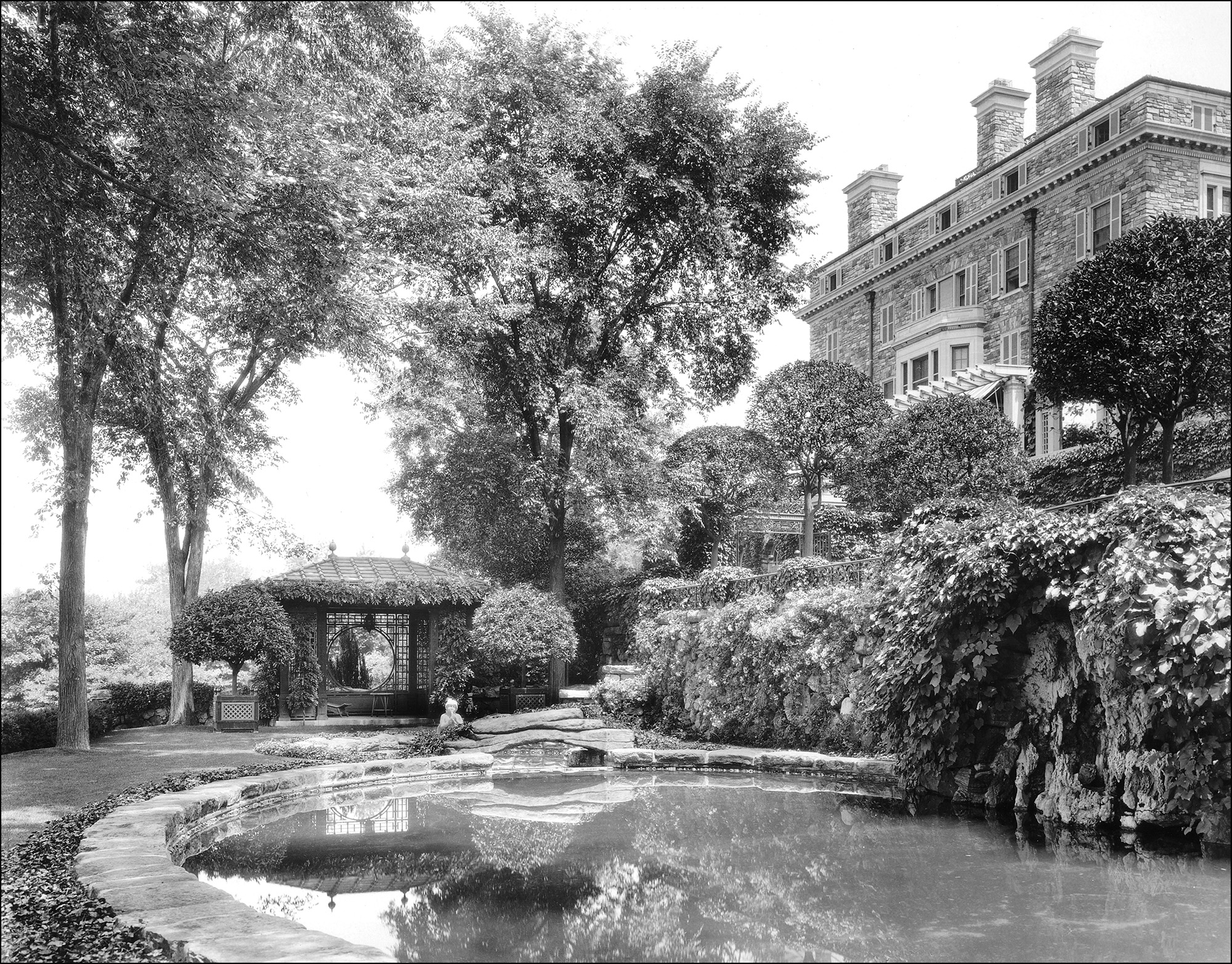

John D. Rockefeller, Sr.’s younger brother, William, was his business partner in Standard Oil. William Rockefeller became the first member of the family to acquire property in New York’s Hudson River Valley when he purchased Rockwood Hall in 1886. He transformed the estate into one of the nation’s grandest houses (204 rooms) and most beautiful landscapes, showcasing rare plants and specimen trees. Rockwood’s gardens, greenhouses, and carriage trails were carefully tended. Some features were even guided by one of the era’s most renowned landscape architects, Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of New York City’s Central Park.

John D. Rockefeller followed suit in 1893, purchasing a large tract of nearby land in Pocantico Hills. His tastes were more restrained than his brother’s, however, and he initially contented himself with occupying the extant Parsons-Wentworth house while undertaking the planning for a grander manor home, a process that would take more than a decade. Parsons-Wentworth burned down in 1902. By 1913, the house known as Kykuit (from the Dutch word for “lookout”) was complete — following a few false starts (Rockefeller wasn’t happy with the home’s first iteration and extensive redesigns were required).

JDR, Sr. occupied the home until his death in 1937, after which John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and his wife, Abby, moved in. When their son, Nelson, became governor of New York in 1959, he took the family home as his residence (Abby had died in 1948 and JDR, Jr., by then married to his second wife, Martha Baird Rockefeller, would soon pass away in 1960). The house and its gardens and art-filled grounds served as the family seat for four generations of Rockefellers, all told, before being passed into public hands.

Passing Private Estates to the Public

In 1976, Kykuit was designated a National Historic Landmark. Former New York Governor and US Vice President Nelson A. Rockefeller, the home’s last occupant, surprised the rest of the family when they discovered upon his death in 1979 that he had bequeathed his one-third interest in the estate to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Thus began a long series of donations by other family members and the reconfiguring of the property as a Trust property with portions rented back to the Rockefeller Brothers Fund for its Pocantico Conference Center. Today, Kykuit and its gardens are open to the public for tours conducted by Historic Hudson Valley, the successor organization to Sleepy Hollow Restorations, established by JDR, Jr. to restore historic homes in the area near Kykuit.

After William’s death in 1922, Rockwood Hall’s land was sold off, some of it to family members and some to investors. When business ventures such as a country club failed and the costs of maintaining the buildings proved too expensive, the physical structures were demolished in 1942. Only the outlines of Rockwood Hall’s foundation are still visible today.

In 1967, Laurance S. Rockefeller announced that the Rockwood Hall property would ultimately become a state park and the planning process began. Since 1983, various parcels have been donated to New York State, creating a preserve of more than 1,400 acres known as Rockefeller State Park Preserve. Today, members of the public are free to walk on the network of carriage roads that John D. Rockefeller, Jr. so meticulously laid out across the property more than a century ago.

Palisades Interstate Park: Preservation Close to Home

Near the Rockefeller family homes, just across the Hudson River on the outskirts of New York City, the Palisades cliffs have been celebrated by famous writers and depicted by painters. Stretching thirty miles along the west bank of the lower Hudson River, the Palisades had been quarried for decades to meet New York City’s demand for cobblestones and building blocks. As the demand for concrete grew in the late 19th century, dynamite blasting began to seriously deface the cliffs, and citizens of New York and New Jersey rallied to protect the shoreline.

Back in 1894, the cliffs stretching from Fort Lee, New Jersey to Piermont, New York had been given to the US government as a military reservation. That gift kept the land intact.

In 1900, New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt appointed a commission to acquire more land running inland from the top of the cliff. Gifts from wealthy New Yorkers, including J. P. Morgan, Mrs. Edward H. Harriman, and John D. Rockefeller, Sr. enabled the land purchases. It was a collaborative effort, combining private philanthropic dollars and public bond issues in two states in 1910, 1917, and 1924.

It was also a collaboration among Rockefeller entities, with funds given by JDR, Sr., the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial.“Palisades Interstate Park Commission,” 1915-1916. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), RG 1, United States, Series 200, General (No Program), Subseries 200.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center; “Palisades Interstate Park Commission,” 1919-1924. Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial records, Appropriations, Series 3, Leisure, Subseries 3_04, Rockefeller Archive Center. These donations built summer camps, park buildings, and hiking trails. At the north end of the Palisades, Bear Mountain, with an inn and campsites, became a model for similar parks across the eastern US.

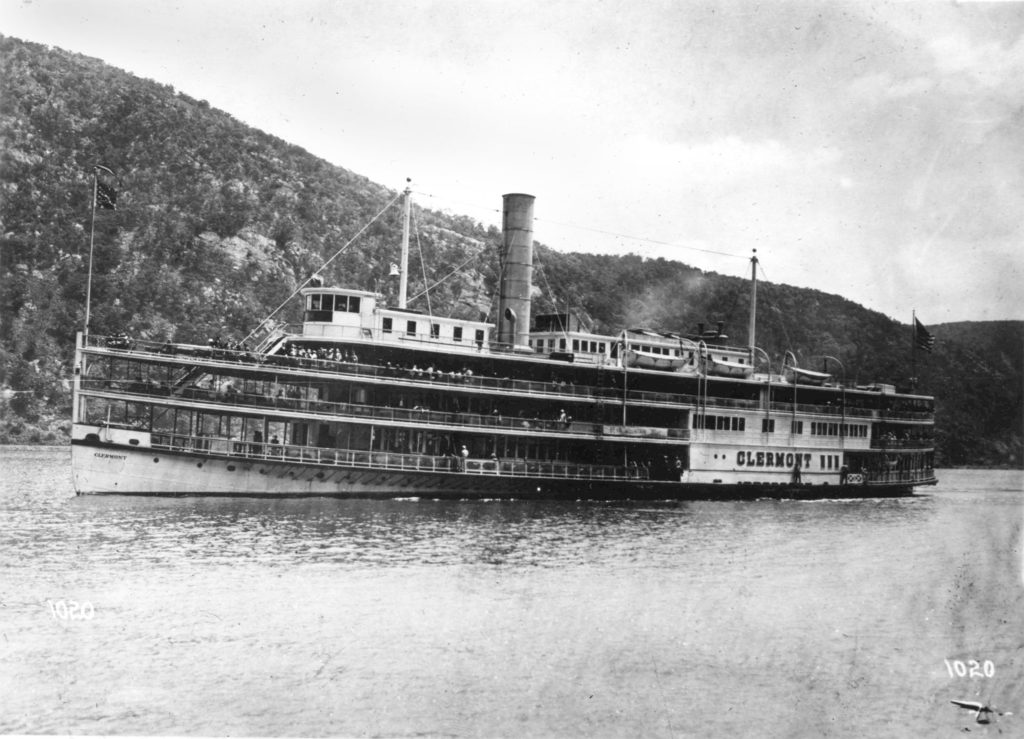

When the Palisades Interstate Park was dedicated in 1909, JDR, Sr. added another $500,000 to his contribution. Later, the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial provided funds to purchase two steamboats, the Clermont and the Onteora, to carry visitors from New York City to the Palisades.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who had often taken his horse on the Fort Lee ferry across the Hudson to ride along the Palisades, continued to be concerned about developments threatening the skyline vista along the top of the cliffs. In 1933, he purchased 700 acres and gave the land to the Interstate Park Commission “to preserve the land lying along the top of the Palisades from any use inconsistent with your ownership and protection of the Palisades themselves.” Ultimately, he gave $11 million for land that would form the Palisades Interstate Parkway.

The Parkway was constructed between 1947 and 1958. JDR, Jr.’s son, Laurance, continued his father’s interest in the Palisades. He served on the Interstate Park Commission from 1939 to 1978. Meanwhile, his brother, Nelson, served as New York Governor from 1959 to 1973. Together, the two Rockefeller brothers were able to preserve not only the storied and scenic Palisades vista, but also to set aside significant land for responsible use and recreation. Laurance’s son, Larry, then succeeded him on the Commission in 1979, furthering the family’s engagement.

Acadia: The First National Park on the East Coast

Cadillac Mountain looms as the tallest of the eighteen mountains on Mount Desert Island, Maine. In fact, it is the highest peak on the Atlantic coastline. European mariners were drawn to the bays and harbors of the island as early as the 1500s. Tourists began to flock to the island in the 1870s and by the turn of the twentieth century, some of the mountain peaks were occupied by small hotels.

Concerns about tourism led some summer residents to band together to purchase the summit of Cadillac Mountain as well as other important sites. Their organization, the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservation, met with Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane in 1913 to discuss the future of Mount Desert Island. Three years later, the land, which had been held as a public trust, was accepted by the US government as Sieur de Monts National Monument. Then, in 1919, it was established as Lafayette National Park, becoming the first national park on the east coast. It was renamed Acadia National Park in 1929.

The Rockefellers in Acadia

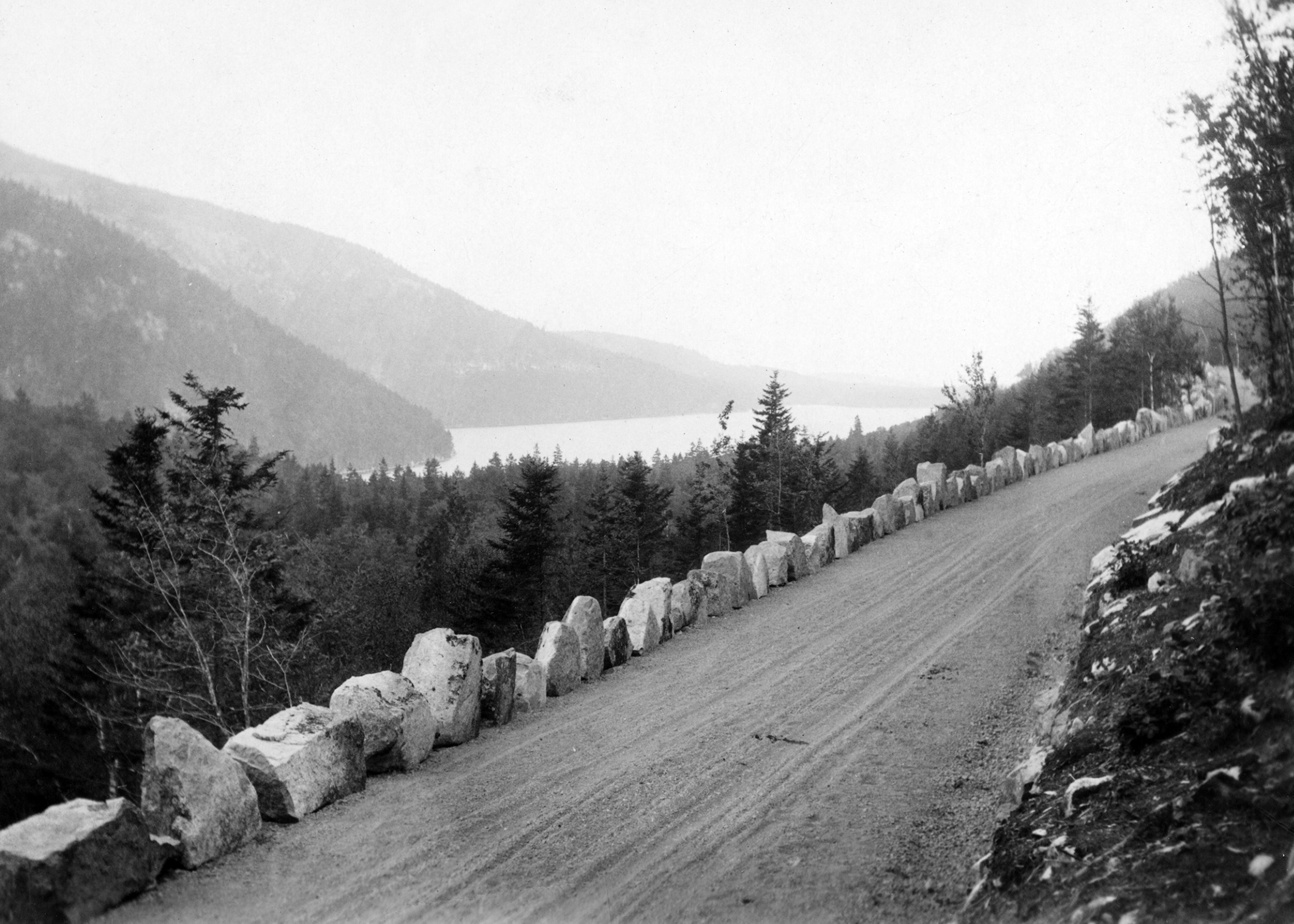

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and his family acquired a summer residence at Seal Harbor in 1910, a 65-room “cottage” that had been built for a Williams College professor. They added to it, eventually bringing its size to 100 rooms, and used it summer after summer. The family was involved in the park from its earliest stages of planning. JDR, Jr. gave 2,700 acres to expand the boundaries of the park. In 1917, he offered to help the federal government build a carriage road system to open up the vistas.

Later, JDR, Jr. would reflect, “One of the things which attracted Mrs. Rockefeller and me most to Mount Desert Island some twenty years ago was that there were no motors on the island. I greatly deplored the pressure to open the island roads to motors and was one of those who opposed their admission to the last.”Seal Harbor Times, August 8, 1928. As quoted in Raymond B. Fosdick, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.: A Portrait. Harper and Brothers, Publishers, p.305. It was a fight he would lose, but in the meantime, he worked with surveyors and engineers to design and complete some 60 miles of carriage roads and bridges, the most elaborate network of roads in the national park system.

Expanding the Function of Parks in the West

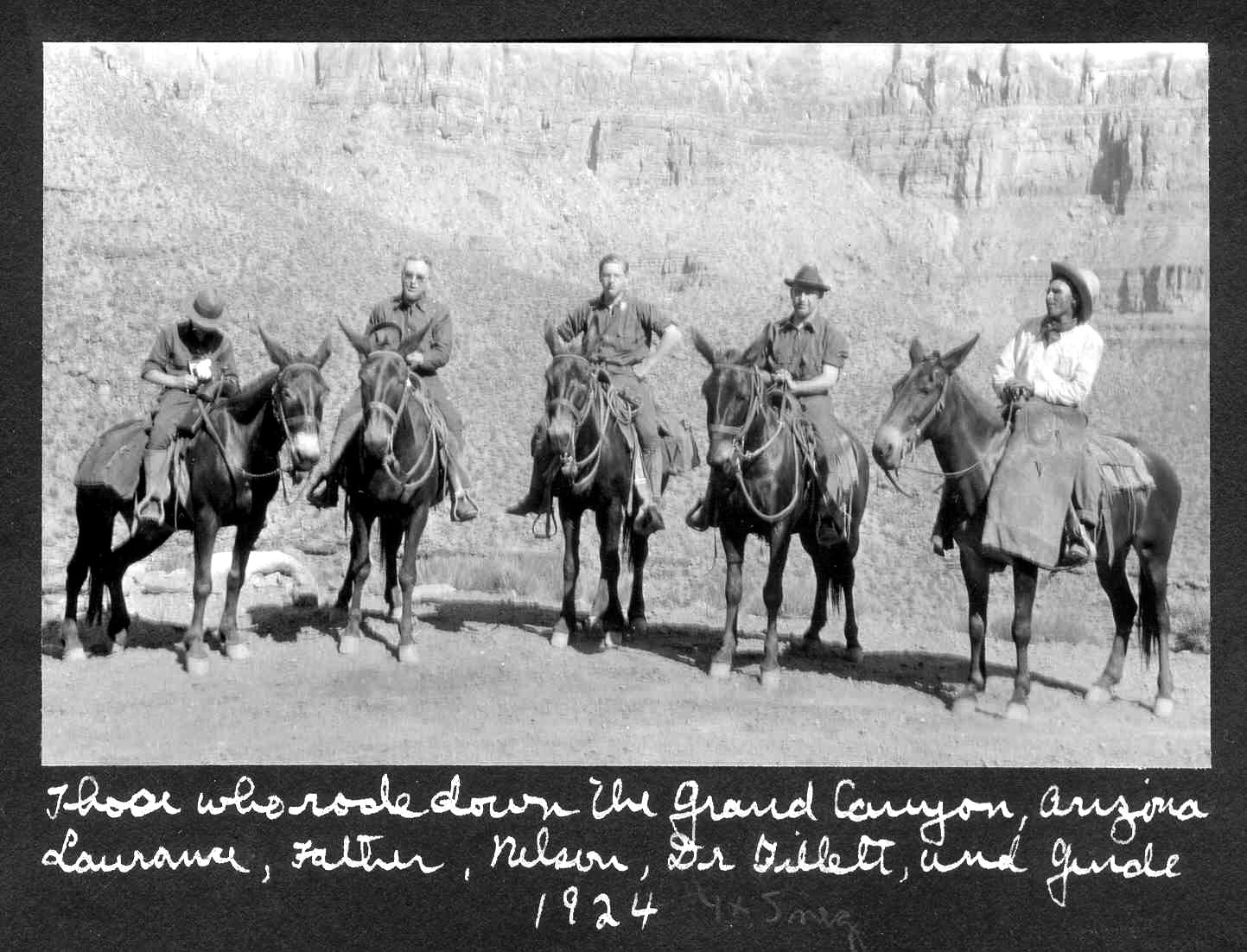

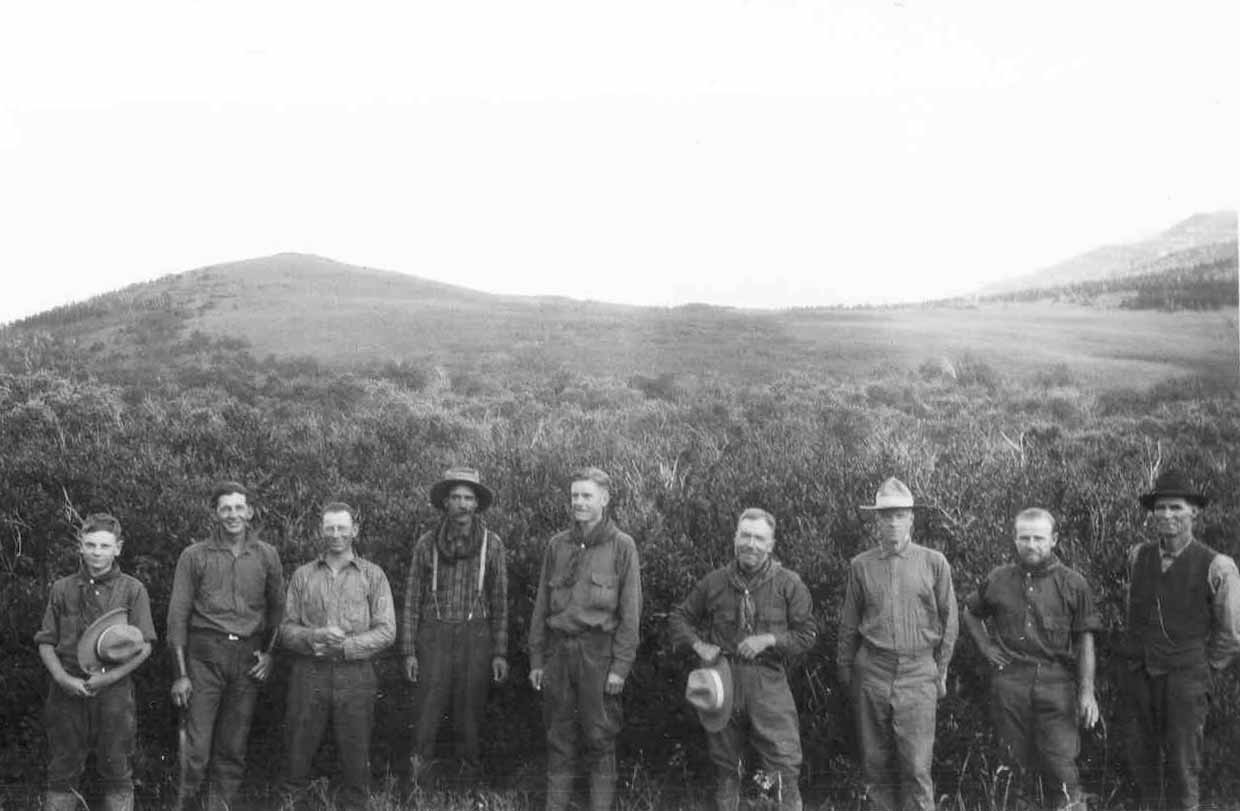

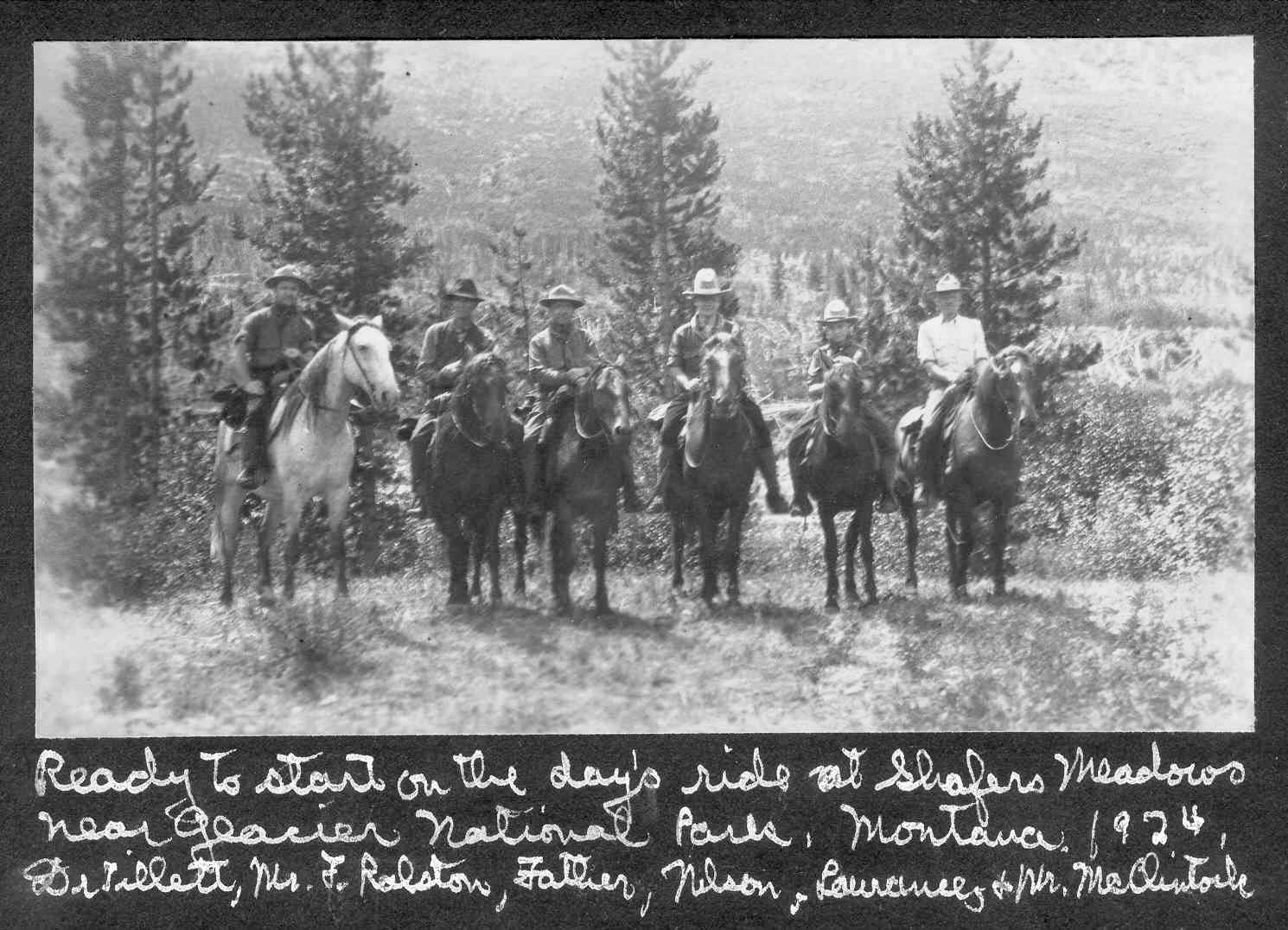

The Rockefeller conservation story extends well beyond the Hudson Valley or even the East Coast. John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s interest in the western United States sparked a similar passion in his sons, and it began with family trips filled with camping and horseback riding. On a trip in 1924, JDR, Jr. took his three oldest sons, John 3rd, Nelson, and Laurance, to visit Taos, New Mexico, Mesa Verde, Yellowstone, Glacier, and Jackson Hole. On another trip in 1926, he took his wife Abby, Laurance, and younger sons Winthrop and David, this time visiting Yellowstone, Jackson Hole, the Grand Canyon, and the California redwoods.

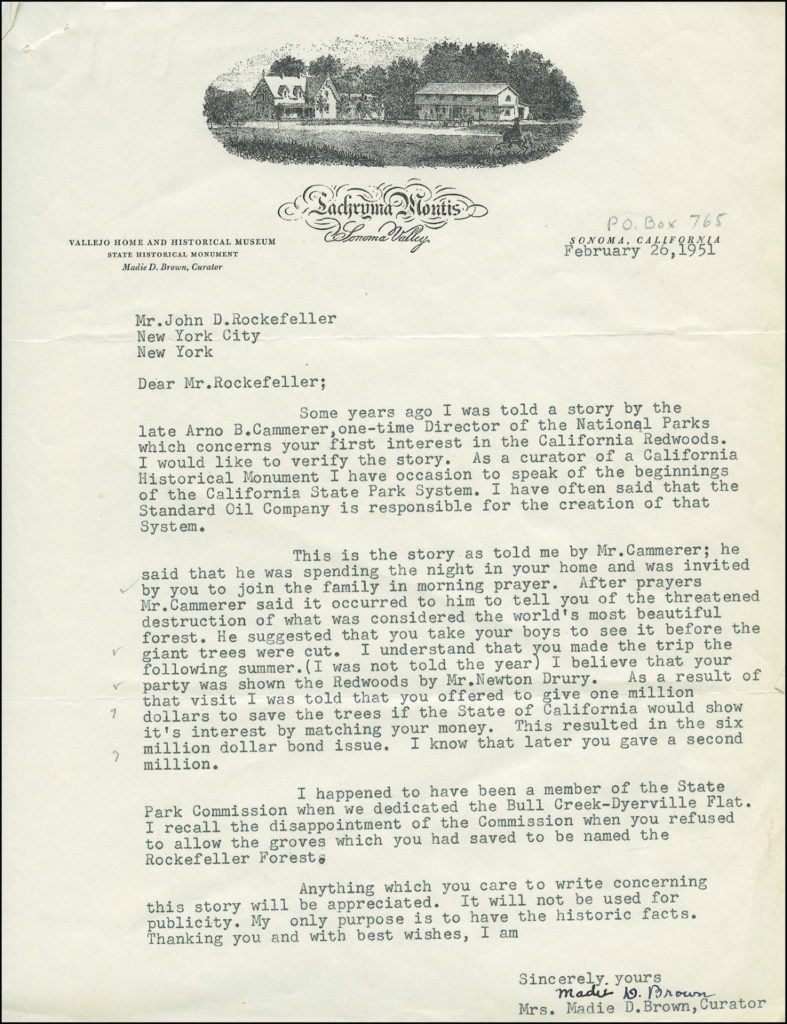

Saving the Redwoods

By 1923, one third of the great redwoods of the California coastal region had been logged, and all but 5,000 of the remaining acres were owned by logging companies. With the US Forest Service predicting total extinction within 100 years, the newly-formed Save the Redwoods League reached out to John D. Rockefeller, Jr. for help. Before he could complete a careful study of the situation, as was his approach to all problems, a specific and outstandingly beautiful stretch called Bull Creek Flat was slated for cutting. Rockefeller quickly mobilized, making an anonymous gift of $1 million to enable the League to begin negotiations to buy the land.“Organizations and Parks – Save the Redwoods League,” 1925-1927. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Cultural Interests, Series E, Organizations and Parks, Rockefeller Archive Center.

On the 1926 trip with Abby and the younger boys, Rockefeller decided to investigate personally. After viewing the trees, he told a reporter, “I am speechless with admiration. I wasn’t prepared for anything so beautiful as the forest we came through today.”Grants Pass, Oregon, Daily Courier, July 9, 1926. As quoted in Raymond B. Fosdick, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.: A Portrait. Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1956, p.317.

JDR, Jr. gave an additional million once the League had proved it could match it (and the state agreed to match it as well). All in all, sum total of $6 million staved off the destruction of the coastal redwoods.

I wasn’t prepared for anything so beautiful as the forest we came through today.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., upon visiting the California redwoods in 1926

Interpreting Mesa Verde

At Mesa Verde, JDR, Jr. began to realize the impact of education and interpretation on visitors’ understanding and enjoyment of the park. Touring the site with Park Service archaeologist Jesse Nusbaum, he asked how he might help with the interpretative aspects of Mesa Verde — always preferring to call it interpretation rather than education. He soon provided funds for an “interpretive center” at Mesa Verde, as well as support for archaeological excavations to ensure that there would be artifacts to populate the center’s exhibits.

The Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial continued this work, developing “trailside museums” at Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon. These Rockefeller initiatives ultimately led to the creation of other museums, inspiring the Park Service to create its Branch of Interpretive Services in 1941.

Protecting the View: Yellowstone and Grand Teton

The journeys to Yellowstone in 1924 and again in 1926 had another impact. Guided by Horace Albright, the park superintendent, the family saw roadside conditions that sullied the pristine views. Roads had been built but there was no Park Service money to clear brush and debris from the sides of the roads. Returning to New York after the 1924 trip, JDR, Jr. asked Albright how he could help improve park aesthetics. He soon sent checks (first for $12,000 and then for $50,000) to help with road clearing.“Organizations and Parks – Yellowstone National Park,” 1924-1927. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Cultural Interests, Series E, Organizations and Parks, Rockefeller Archive Center.Once again, the government took a Rockefeller initiative to scale, when Congress subsequently allocated money to clear and maintain the roads.

In the summer of 1926, when Junior and Abby returned with the younger boys to spend twelve days in Yellowstone, they again met up with Horace Albright.“Travel Records, United States – Western Trip (June-July 1926),” John D. Rockefeller, Jr. papers, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Personal papers, Series Z, Subseries 2, Rockefeller Archive Center. He guided them through the Tetons for two days, always finding the very best spots for photos.

On their way to Yellowstone, Albright took the family along a bluff overlooking the Snake River and told them about the struggle to save Jackson Hole from shanty town developments, billboards, bars, and other touristic structures. They viewed burnt-out gas stations and abandoned shacks, a dance hall, and a place called the Last Chance Hotel. Most of these structures were on privately owned land.

Albright told the Rockefellers about his vision, shared with a few like-minded others, for expanding the park beyond Yellowstone.

An “Ideal Project”

Albright then came to New York in November 1926, equipped with maps and plans. JDR, Jr. had asked for the maps specifically, so that he could determine the costs of acquiring properties that would expand Yellowstone. Albright proposed purchasing some 14,000 acres on the west side of the Snake River.

But JDR, Jr. sought a “more ideal” project, one that would accomplish more, and thus wanted to add land in upper Jackson Hole, Wyoming. In the end, he committed to the purchase of more than 30,000 acres at a cost of $2 million. Rockefeller planned to give the land to the US government, thereby preventing the spread of the kind of ramshackle commercial development he had observed on his last trip out West.

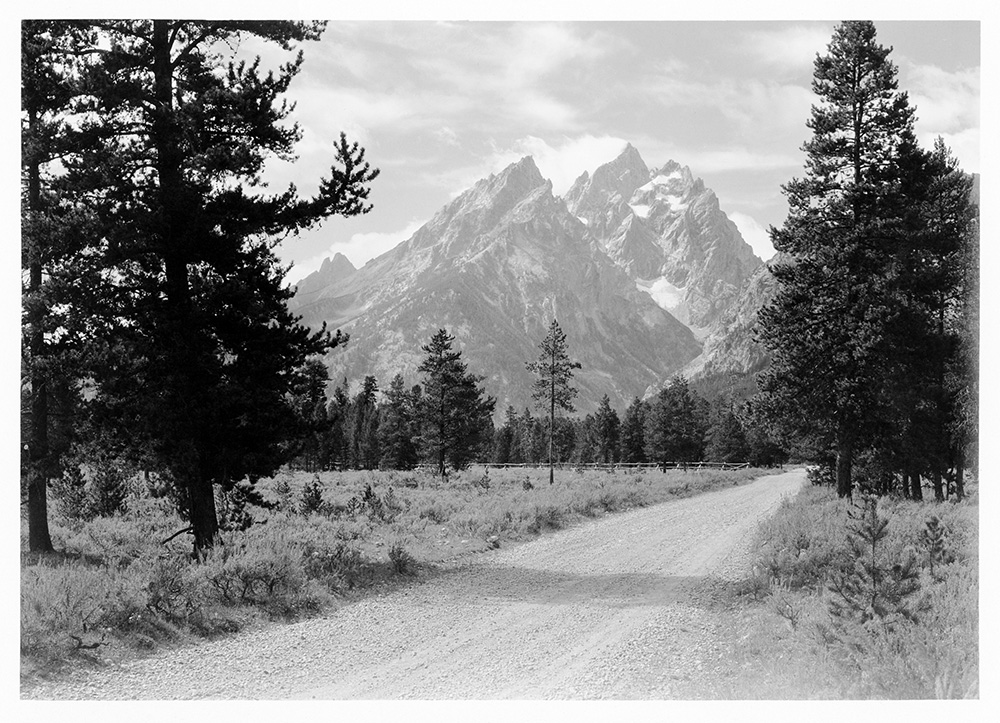

He explained his reasons for the purchases some years later: “The two reasons which have moved me to consider this project are: first, the marvelous scenic beauty of the Teton Mountains and the Lakes at their feet, which are seen at their best from the Jackson Hole Valley; and second, The fact that this Valley is the natural and necessary sanctuary and feeding place for the game which inhabits Yellowstone Park and the surrounding region. I am told that only through the preservation as a sanctuary of the Jackson Hole country can the buffalo, elk, moose and other animals be permanently maintained and preserved from extinction in the West.”Raymond B. Fosdick, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.: A Portrait. Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1956, p.312.

Grand Teton became a national park in 1929, but it was not until 1950 that the larger portions of the Jackson Hole Basin were incorporated into the park, despite the fact that FDR had declared the Basin a national monument in 1943. Rockefeller’s Jackson Hole purchases, which ultimately totaled $17.5 million, were controversial. Opposition from ranchers, loggers, the Forest Service, and other locals stalled the park plans. Senate investigations that began in 1932 delayed the federal acquisition of the land.

Rockefeller continued to visit the Tetons throughout his life. In 1952, he made another purchase, giving $6 million (and, ultimately, $13 million through the funding vehicle, Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc.) for Jenny Lake and Colter Bay, to build a hotel and cottages at Jackson Lake. Although his initial purchases had aimed to prevent unsightly commercial development, nevertheless this hotel venture raised increasingly important questions as US tourism ballooned during the prosperous postwar years. The tension between pure conservation and responsible use would later become a major focus of JDR, Jr.’s middle son, Laurance.

Related

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Creates a National Park

Who defines the public good? The showdown caused when a wealthy philanthropist bought land and tried to give it to the American people.

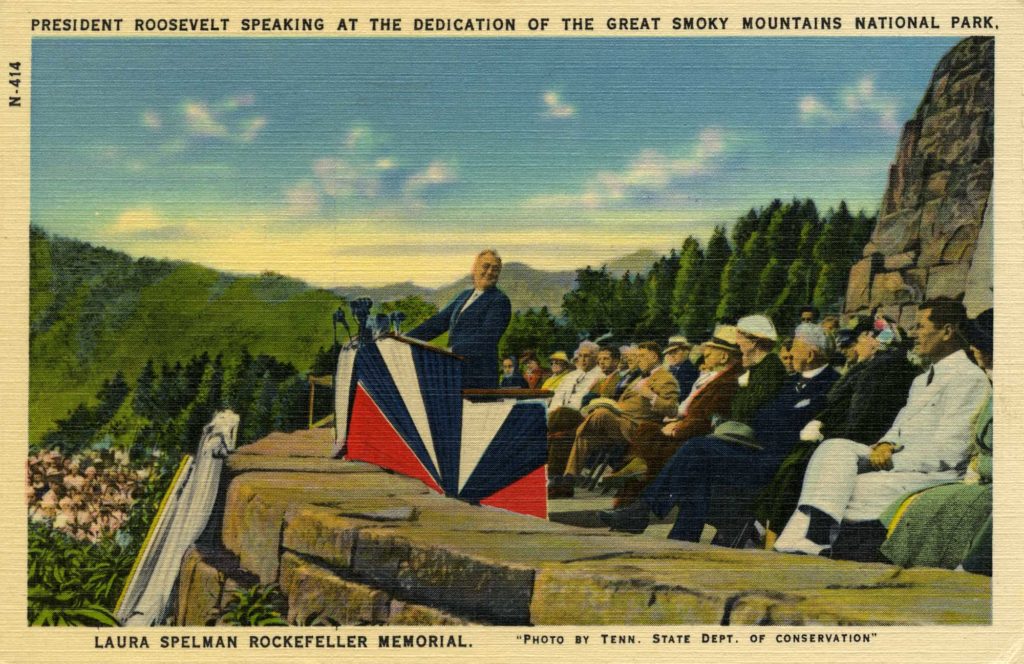

The Great Smoky Mountains and Shenandoah

Although drawn to the West, JDR, Jr. made many contributions to parks in the East. In 1924, he provided funding for a study to create a park in the southern Appalachian Mountains. Two great national parks in the southeastern United States were enabled by this study. The Shenandoah and Great Smoky National Parks are linked physically by the Blue Ridge Parkway. They also share a history.

Both began as initiatives of private citizens and both were approved by acts of Congress in 1926, approval contingent on raising enough private money to buy the land. In Virginia, where 60 gently rolling peaks of the Blue Ridge Mountains shape the Shenandoah National Park, private donors contributed $1.2 million to purchase land; it was then deeded to the federal government.

In North Carolina and Tennessee, the fund-raising challenges proved greater as they sought to purchase over 500,000 acres in 6,600 separate parcels. Citizens of the two states had donated about $5 million for land acquisition by 1928, but were still millions short of the total amount needed. JDR, Jr. suggested that the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial might contribute $5 million — explicitly, he said, to honor the spirit of his mother, for whom the Memorial was named. A plaque along the parkway still honors her today.

The Most Popular Park in the US

The rationale for these parks and parkways linked regional economic development with natural conservation. The parks and highways would preserve the landscape and natural resources from heedless development by opening the area to recreational tourism. This was one of the animating park ideas of the 1920s and 1930s.

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is today the most visited park in the US, with some 9.5 million visitors annually. With peaks rising to over 5,000 feet and vegetation so varied that more than 1,400 species of flowering shrubs and trees have been counted, it is also the most accessible of the nation’s parks, thanks to its parkways, which Congress funded in 1933 as part of its New Deal programs.

Third Generation Rockefellers and the Parks

JDR, Jr.’s six children each pursued their own conservation interests. David Rockefeller was most devoted to Acadia, laying some of its trails by hand; Winthrop worked in his adopted home state of Arkansas (where he became governor in 1966), concentrating on the Ozarks and on the Buffalo River; and Nelson (often collaborating with Laurance) was committed to preserving and expanding parkland throughout New York State. In 1968, their only sister, Abby “Babs” Rockefeller Mauzé, founded and became president of the still-extant Greenacre Foundation, which she created to maintain and operate New York City parks for the benefit of the public. Through the Greenacre Foundation, in 1971 Babs established a lush, verdant “pocket park” oasis, complete with waterfall, in New York City’s midtown.

The youthful western trips had a lasting impact on all the brothers, but especially on Laurance, who would spend his honeymoon with Mary French Rockefeller at Colter Bay near Jackson Hole, where he eventually built a home and constructed his first hotel. Though all of his siblings were devoted in their own ways to nature and preservation, Laurance was the one most enthralled by natural conservation, and the most engaged with national conservation initiatives, preservation, and outdoor recreation. As time went on, the “pleasure and satisfaction” Laurance described getting from his visits to Jackson Hole became a driving force in how he raised his own family. As he wrote in a 1950 letter, he treasured this location for the “constructive influence it has on the children.”

In 2008, Laurance donated the family’s JY Ranch property in Wyoming, originally purchased by JDR, Jr. in 1932, to the National Park Service. In June 2008, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Preserve Center was dedicated in Grand Teton National Park and a series of public trails was created on the former JY Ranch property.

…the pleasure and satisfaction of our visits to Jackson Hole… the constructive influence it has on the children…

Laurance S. Rockefeller, 1950Laurance S. Rockefeller, correspondence about the preservation of Menors Ferry and the Snake River crossing at Jackson Hole Preserve. Full text available online. Menors Ferry, Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Cultural Interests, Series E, Organizations and Parks, Rockefeller Archive Center.

Tourism Plus Environmentalism

The Virgin Islands National Park, on the tiny island of St. John, has steep mountains, tranquil bays and inlets, and an exceptionally mild climate. Inhabited over the centuries by Caribs, Spaniards, Danes, and enslaved Africans, the island came into American possession in 1917. By the late 1930s, the federal government was thinking about creating a national park on the island, but despite surveys for a park, the government took no immediate steps to establish one.

Soon after acquiring the nearby Caneel Bay Estate in the early 1950s, Laurance S. Rockefeller took up the pursuit of a national park on the island. With the help of his father and the Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc., he acquired nearly 5,000 acres. Congress passed legislation to create the Virgin Islands National Park in 1956. The Rockefeller Brothers Fund also contributed to the park’s establishment.

The park offered an opportunity for Laurance to develop his growing eco-tourism ideas and his hopes of balancing economic uses with conservation goals. He pursued similar agendas in his properties at Mauna Kea in Hawaii and the Dorado Beach Hotel in Puerto Rico, though only Caneel Bay was appended to a national park. These initiatives led Laurance to establish the business he called RockResorts. The Caneel Bay resort opened in 1956 when the national park was dedicated, but sadly has been closed since 2017 after sustaining catastrophic damage from Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller

Some parks tell stories about the preservation of pristine natural places. Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historic Park, on the other hand, is a working landscape restored. It also bears a connection to Laurance Rockefeller, and it tells the story of three families and their stewardship of the land.

George Perkins Marsh, author of the classic Man and Nature, published in 1864, was born in Woodstock, VT. As a boy, he wandered up Mount Tom and through Woodstock’s hills and fields. Those who know of him today might regard him primarily as the father of the American conservation movement. But he was also a historian, linguist, politician, and diplomat who spent the last two decades of his life in Italy.

The hills he explored in his youth were, in contrast to how we think of Vermont today, barren — almost completely denuded by logging. Marsh saw how rain and melting snow washed soil down the mountainsides. He observed how this erosion affected both vegetation and animal life. He began to view nature as a complex system, concerned early on about the ecological consequences of deforestation. Wherever man “plants his foot,” he wrote, “the harmonies of nature are turned to discord.”George Perkins Marsh, Man and Nature. Charles Scribner, 1864, 35-36.

Changing the Model: from Conservation to Ecology

While conservation is often motivated by a sense of loss, from bison killed on the Great Plains to California redwoods lost to loggers, ecological environmentalism thinks more profoundly about the interconnected relationships of the human and natural environments. At its core, this kind of environmentalism poses scientific questions. Marsh now seems prescient, anticipating questions that are commonplace today about the interdependence of humankind and the natural world as he pondered soil conservation and the protection of watersheds. His was a viewpoint that Laurance S. Rockefeller would later adopt.

The Marsh home site was acquired by Frederick Billings, a native of Vermont who had moved to San Francisco and become a successful lawyer and investor. While in the West, Billings was inspired by the beauty of Lake Tahoe and Yosemite and worked to preserve them in the 1850s and 1860s. He returned to Vermont in 1864, the year Marsh published Man and Nature (and the year that Lincoln granted Yosemite to California).

After buying the Marsh property, Billings built a larger house on it and took Marsh’s writings to heart. Seeing the stripped Vermont hills in need of reforestation, he asked how to restore what had been lost. He looked at farming and dairy operations and asked how to use science and technology to prevent depleting the land.

Sustainability and Working Landscapes in Vermont

Mary French Rockefeller, wife of Laurance and granddaughter of Frederick Billings, inherited the house. Her husband added surrounding forests and farmlands to the property, amassing some 500 acres in all. The house, largely because of George Perkins Marsh’s writings and Billings’ support for reforestation, was named a National Historic Landmark in 1967, a first step toward becoming a national park.

Laurance and Mary Rockefeller donated the property to the nation, and it was designated the Marsh-Billings National Historical Park by an act of Congress in 1992. The Rockefeller name was added later, after Mary’s death in 1997.

The theme of this unusual national park is stewardship. It is an idea that links the conservation of natural resources to the historic preservation of landscapes and buildings. Designating this theme made concrete the responsibility that one generation has to the next, and demonstrates that the restoration of natural environments is possible.

Laurance’s stewardship, which continued until his own death in 2004, was acknowledged with the Theodore Roosevelt National Park Medal of Honor and the Congressional Gold Medal, given for his contributions to natural conservation and historic preservation.

The legacy of the Rockefellers in conservation and ecology has continued to the present, with family members’ involvements ranging from the Audubon Society to the National Resources Defense Council. What many people don’t know, however, is how wide the family’s reach has been for more than 100 years in securing, preserving, and shaping some of the nation’s most storied and treasured natural locations.

This piece is an expansion of a talk by James Allen Smith entitled “An Eye for Nature,” given at the Pocantico Center of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund.

Further Reading

- Thomas A. Krianz, “Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020 Observations on John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s and the Rockefeller Foundation’s Involvement with Colorado’s Work-Relief Program.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2020.

- Elizabeth Engle, “Cultural Resources in a “Natural” Park: Early Preservation Efforts at Menor’s Ferry in Grand Teton National Park.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2013.

- Elizabeth Engle, “Colter Bay Village: Understanding the Historic Significance of the Recent Past in Grand Teton National Park,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2010.

- David Stradling, “The Hudson River and the Boundaries of Environmentalism.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2008.