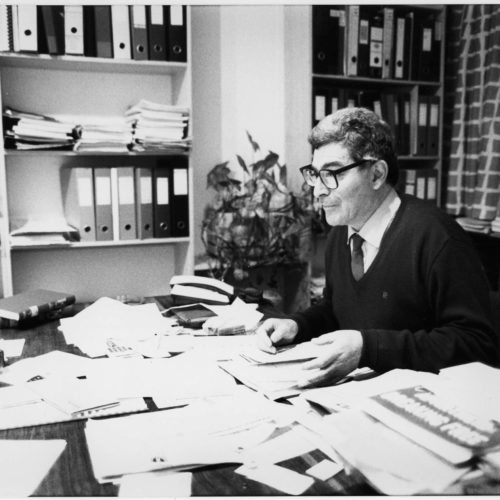

In 1910 the Carnegie Foundation issued a landmark report on medical education. Abraham Flexner authored the report, titled Medical Education in the United States and Canada, or Bulletin No. 4, analyzing the educational programs of 155 medical schools throughout Canada and the United States. His research concluded that medical education in North America was woefully inadequate in every aspect, including its lack of laboratory facilities, disorganized administrative practices and lack of teaching and curriculum standards. Flexner’s recommendations profoundly influenced the leading philanthropists of the age, including John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (JDR Sr.), and led to the transformation of medical education in the United States and the world.

Leading the Charge

Spurred by Flexner’s report, the General Education Board (GEB) and later, the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) called for a transformation of, and investment in, medical education in the US. Medical education, as Flexner described it, was mostly a for-profit enterprise undertaken by small schools staffed by a few, part-time doctors. In many cases medical education involved no laboratory work or practical training. Students were often admitted without a high school education, and curricula varied widely from school to school.

General Education Board and Rockefeller Foundation officials well understood that the success of their program might shutter some of the worst medical schools, while the best, with their help, would compete with the finest schools in Europe. The RF mandated a relationship between hospitals and any medical school that the Foundation funded. The RF also required teaching staff to be under university control and devoted solely to teaching rather than balancing their duties with private, for-profit practice.

The GEB took the lead in the improvement of medical education in the United States. Directing the medical education program was Flexner, who became Secretary of the GEB in 1913. Under his advisement the first grants towards the improvement of medical education went to Johns Hopkins University in 1913. Hopkins received an annual grant to develop its clinical programs, including medicine, surgery and pediatrics. The success realized at Hopkins inspired further grants, including significant sums for the medical programs at Yale and Vanderbilt Universities. It also motivated JDR Sr. to earmark a further $45,000,000 for the GEB’s program in medical education.

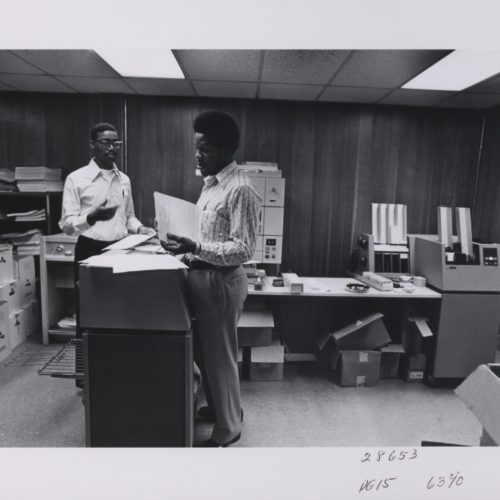

Bridging the Gap

The GEB also supported medical schools at Historically Black Colleges. The biggest recipient of this support was Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. Support for Meharry began in 1916, and over thirty years the GEB contributed approximately $8 million, helping to create a first-class center for African-American education in medicine, nursing and dentistry. Beginning in 1947 the RF made contributions to the school in order to off-set the increasing costs of operation. Upon announcing this additional support a GEB staffer noted,

In the training of Negro doctors Meharry Medical College easily occupies first place. More than half the country’s Negro practitioners are its graduates, and the College’s present enrollment is greater than the total of Negro medical students in all other American medical schools.

General Education Board, 1947June 13, 1947, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 1.1, Series 200A, Box 98, Folder 1182.

In 1919, the Division of Medial Education was established within the RF and administered by the International Health Division (IHD). The division became responsible for the improvement of medical education outside of the U.S. The earliest years of the program focused on surveying the state of medical education worldwide and funding targeted institutions for improvements.

A New Focus

Rockefeller Foundation officials recognized early that to complement their programs in hookworm, malaria and yellow fever eradication they needed a cadre of well-trained public health officials. As noted in the 1923 RF Annual Report:

… medical education plays an essential part in the leadership and success of public health work. The Rockefeller Foundation is concerned, therefore, in aiding influential medical schools in many parts of the world to improve their facilities, to strengthen their teaching staffs, to perfect their methods, to maintain high standards, and gradually, in the words of a distinguished British medical authority, to ‘permeate the curriculum with the preventative idea.’[2]

1923 Annual ReportThe Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report 1923 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 1923) 39-40. (Link to PDF on Rockefeller Foundation Website)

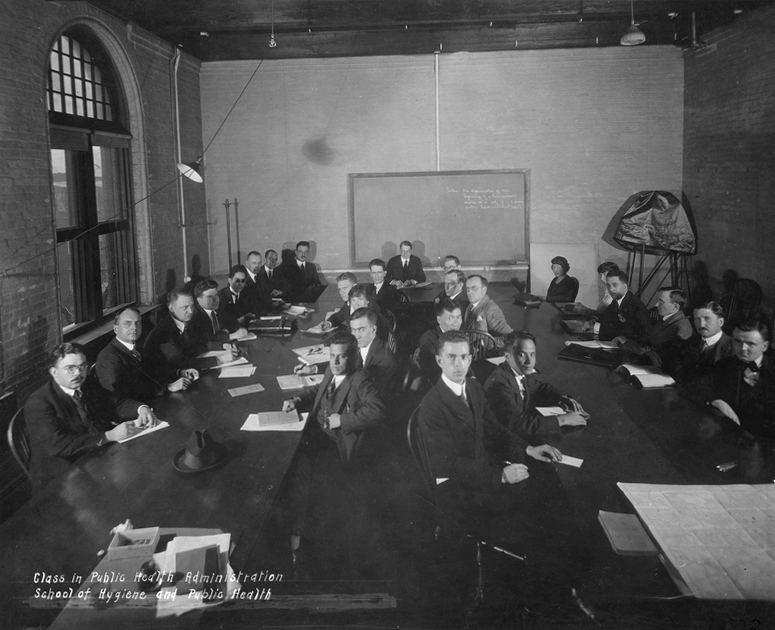

The first university to benefit significantly from the investment in schools of public health was Johns Hopkins University. Through extensive funding beginning in 1916, the RF created the School of Hygiene and Public Health at Johns Hopkins, and the school quickly became a model of public health education.

Internationally, the two biggest recipients of RF funding were the University of Toronto and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Writing to Sir Alfred Mond, the British Minister of Health, of the RF’s $2 million appropriation, Wickliffe Rose noted,

The object of the Trustees is the advancement of world health in the widest sense, and they are the more glad that they can make the offer at a moment when the outlook seems a little brighter for the close drawing together of the nations in the bonds of mutual understanding and of common effort for human welfare.

Wickliffe Rose, 1922Letter from Wickliffe Rose, IHD to Sir Alfred Mond, Minister of Health, February 8, 1922, RAC, RG 1.1, Series 401, Box 2, Folder 11.

By 1929 the GEB and the RF shifted their focus from institutional development in medical education to research initiatives. In less than two decades the GEB had transformed American medical education into one of the best systems in the world, while the RF had invested over $25 million to build institutes of public health across the globe.

Public Health at Johns Hopkins

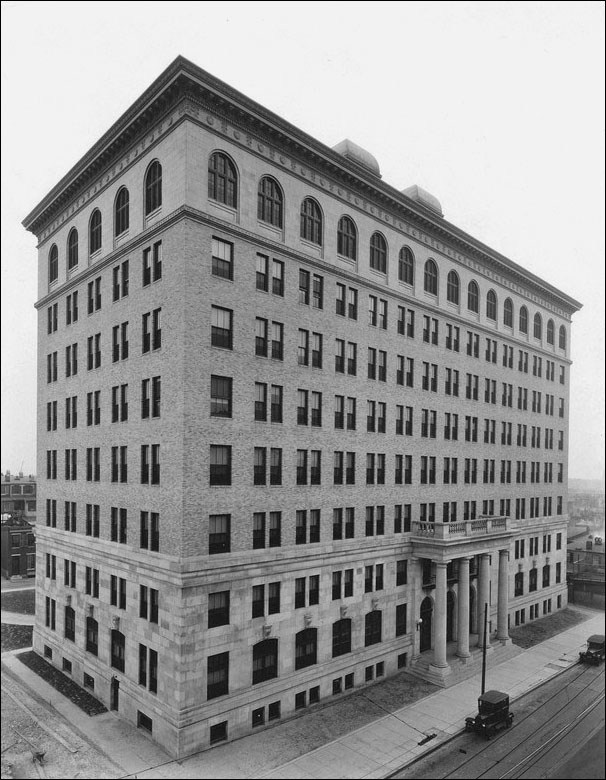

The School of Hygiene and Public Health at Johns Hopkins was founded in 1916 with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. The school was the first of its kind in the United States and became enormously influential in the field.

Preparing for Success

The RF’s decision to invest in public health education was a natural extension of its already established role in improving basic medical education and conducting global campaigns against targeted diseases. Prior to its investment in public health education, the RF had waged international health campaigns to eradicate hookworm, malaria and yellow fever. These campaigns demonstrated the need for appropriately educated health officers to organize and manage the campaigns and to emphasize the importance of prevention to local populations and governments. Success in these campaigns depended upon selecting and educating these officers.

The prospect of public health education was first explored in 1913 in a report prepared by Wickliffe Rose and William Welch, former Dean of Johns Hopkins Medical School and a General Education Board (GEB) Board Member. The report emphasized the need for the RF to become involved in public health education and outlined a plan for it to do so.

Choosing Johns Hopkins

The decision to establish the first public health institute at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University came after a survey conducted by Wickliffe Rose, Abraham Flexner and Jerome Greene on behalf of the GEB. These men visited and surveyed four institutions in competition for the RF funding, including Columbia University, Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) and Johns Hopkins University. The final report of this survey acknowledged that Columbia, Harvard and Penn possessed superior supporting university departments and were located in cities with strong health departments. Although Hopkins was described as “inferior” in certain areas, Hopkins was unanimously chosen based on the potential of its existing medical school, which was described as “…the University’s greatest asset.” The authors continued,

It is a genuine University department, on the clinical as well as the laboratory side. The faculty is a small body, and, since the introduction of the full-time scheme, entirely homogenous in character, animated by high ideals and very efficiently led.

General Education Board Report, 1916Institute of Public Health, Final Report of the General Education Board, January 26, 1916, Rockefeller Archive Center, RG 1.1, Series 200L, Box 185, Folder 2226.

The first administrative records of the program reflect a sense of optimism about the institution’s future. The school promised:

- To offer all kinds of public health training

- To work out standards of education

- To promote research

- To form connections with other training centers at home and abroad

- To offer public health fellowships on an international scale

- To co-operate with Government agencies

- To render valuable aid to the International Health BoardMinutes of the Rockefeller Foundation, December 5, 1917, Rockefeller Archive Center, RG 1.1, Series 200L, Box 185, Folder 2225.

The school at Johns Hopkins grew to be a model of public health education and was referred to by RF President George Vincent as the “West Point of public health.”Raymond B. Fosdick, The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation (New Brunswick, USA: Transaction Publishers, 1952) 42. Under the directorship of Welch, the school attracted the best faculty working in fields such as preventative medicine, sanitation and bacteriology. The curriculum was inter-disciplinary and offered students experience in public health research work, as well as the practical training to work in city and state health departments or as RF field staff.

From 1916 to 1947 the RF contributed $8 million in funding to the School of Hygiene and Public Health. Further funding was provided after 1948 for the emerging fields of mental health care and public health nursing.

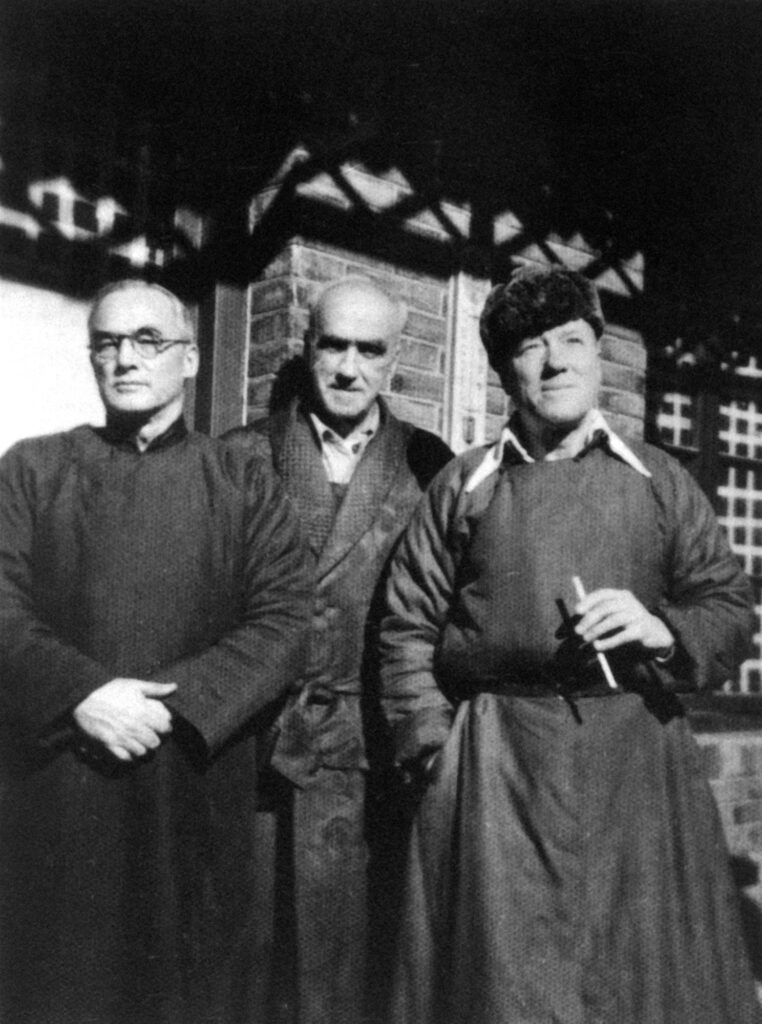

Western Medicine in China

From its earliest years, the Rockefeller Foundation took particular interest in China, a legacy of the Rockefeller family’s special interest. The China Medical Board (CMB) was created in 1914 as one of the first operating divisions of the Rockefeller Foundation (RF). Provided with a $12 million endowment and separately incorporated as CMB, Inc. when the Foundation was reorganized in 1928, the Board’s aim was to modernize medical education and to improve the practice of medicine in China.

Surveying China

China was a long-standing interest of both John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (JDR Sr.), and his son. For decades they and their fellow Baptists had supported missionary work in Asia. Beginning in the early 1900s, Frederick Gates encouraged them to devote even more attention to that region. In 1908, five years before the Foundation was created, the Rockefellers funded a commission headed by Edward D. Burton, a University of Chicago professor of theology. He and other educators traveled to China to explore the potential for philanthropic work there.

In its final report the Burton Commission argued that a Western-sponsored educational program in science and medicine for elite Chinese students could succeed, despite a difficult political climate. One of the first actions of the newly created RF was to organize a conference about China in New York in early 1914. The Foundation later dispatched two additional survey groups, the China Medical Commissions of 1914 and 1915, to gather more information about how such an educational program could operate.

Following the model established by Abraham Flexner’s survey of U.S. medical education, the 1914 Commission set out to appraise medical education in both missionary and Chinese schools. It found appallingly low standards throughout the country. The report concluded that “the country is so vast, and the resources available for dealing with the problem are so limited as yet, that the need of outside assistance is still very great.”Internal Memorandum, The Rockefeller Foundation, March 7, 1915, Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), RG 2, Family Records, Series O, Box 11, Folder 92. The CMB was formed to meet those challenges, and Wallace Buttrick was named its first director.

The Foundation’s approach to Chinese medical education would inevitably follow the general patterns for reforming U.S. medical education advocated in the 1910 Flexner report and most fully embodied in the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Medical education in China would be scientifically rigorous and adhere to Western standards. And, in a decision with long-term consequences, instruction would occur in English. Consequently, the school could reach only a small, elite percentage of the population. Yet in a country of 400 million people then served by fewer than 500 well-trained doctors, such an approach stood to be criticized. Nevertheless, the CMB set out to build a medical school in China that it hoped to make the equal of Johns Hopkins.

[T]he country is so vast, and the resources available for dealing with the problem are so limited as yet, that the need of outside assistance is still very great.

Rockefeller Foundation Memorandum, 1915

Building for the Future of Healthcare in China

The RF entered China with an ambitious goal: to build modern medical schools in both Peking and Shanghai. By purchasing the Union Medical College from the London Missionary Society in 1915, the Foundation took its first steps toward that goal. Over the next six years the Foundation assembled a faculty of fifty professors and upgraded and enlarged the facilities of what was soon called the Peking Union Medical College (PUMC). Particular attention was paid to the school’s architecture and campus plan. According to the RF’s 1917 Annual Report,

While the buildings will embody all the approved features of a modern medical center, the external forms have been planned in harmony with the best tradition of Chinese architecture. Thus they symbolize the purpose to make the College not something foreign to China’s best ideals and aspirations, but an organism which will become part of a developing Chinese civilization.

Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1917The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report 1917 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 1917) 224.

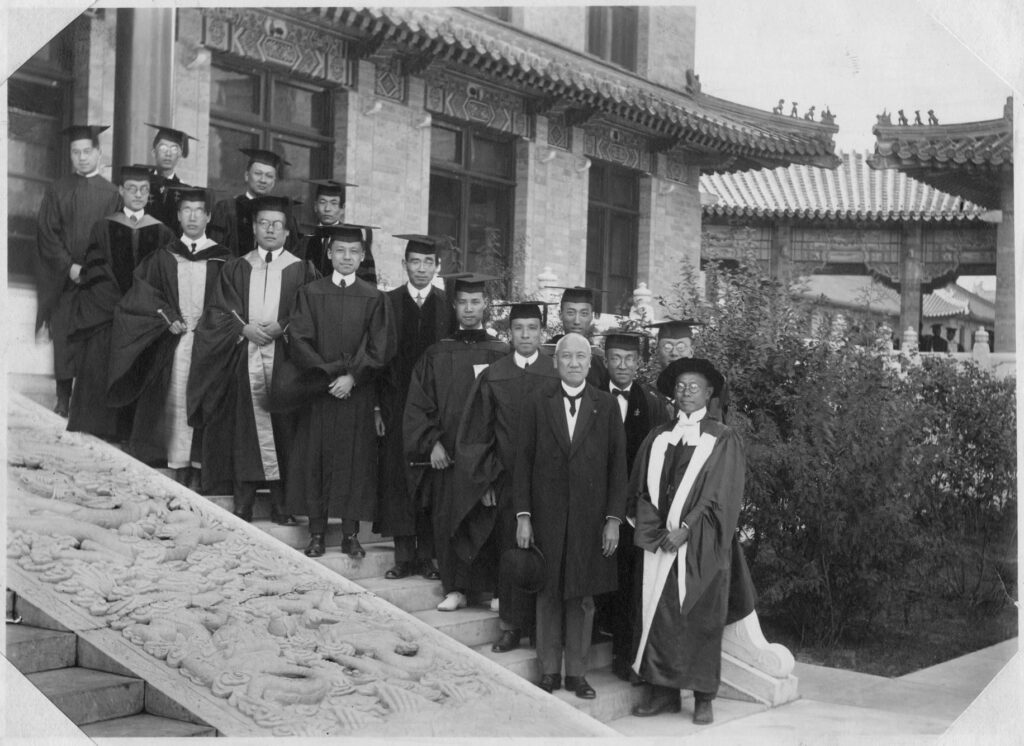

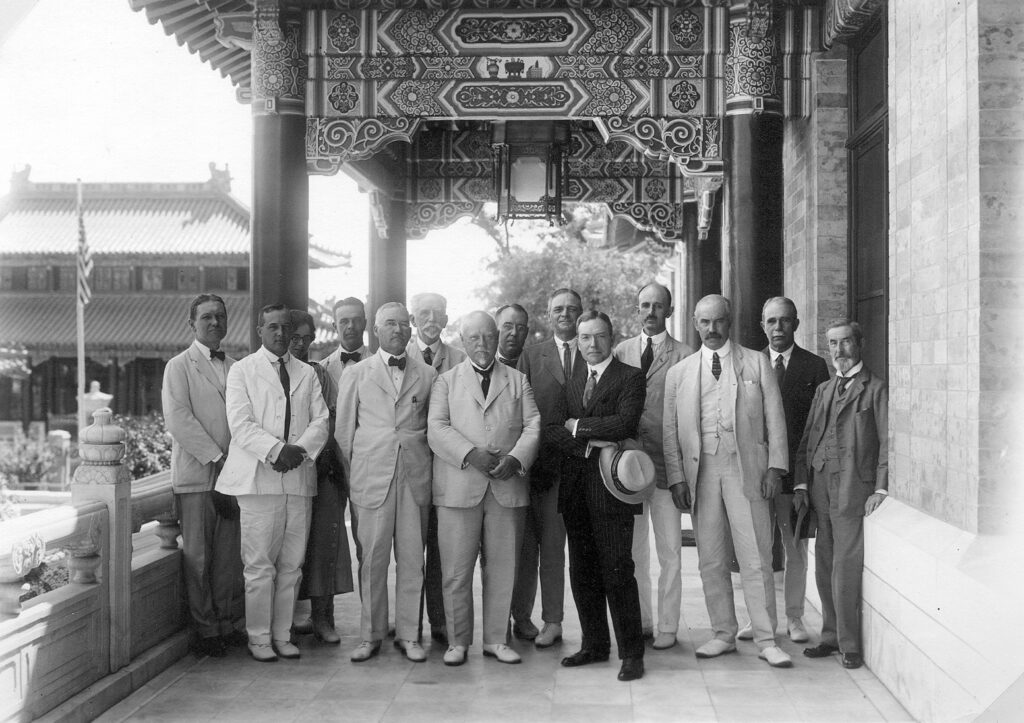

PUMC opened its doors in 1919, under the de facto directorship of Roger S. Greene, resident director of CMB. The 70-acre campus would ultimately encompass more than 50 buildings, including a hospital, classrooms, laboratories, and residences. But in New York Rockefeller officials grew concerned about the mounting costs of PUMC and were soon forced to scrap their plans for Shanghai. From an initial construction estimate of $1 million in 1915, expenses ballooned to $8 million in capital expenditures by 1921. The operating budget more than doubled between its first year of operation and 1921. Nevertheless, the medical school and its new campus were deemed worth celebrating. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (JDR Jr.) led an impressive delegation to China for the 1921 dedication ceremonies.

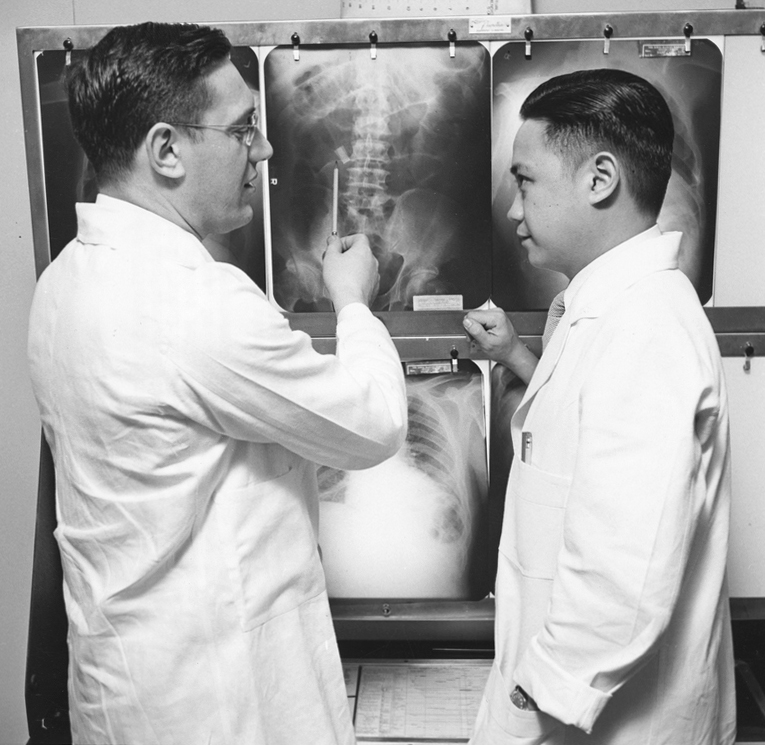

PUMC’s initial contributions toward the improvement of medicine in China, though consequential, were inevitably limited in scale. Its graduating classes were small, in part because its standards remained high and its curriculum at the outset was exclusively in English. Between 1924 and 1943, PUMC produced only 313 doctors, more than half of whom would continue their studies abroad through CMB fellowships. Upon their return many of these doctors ultimately became leaders in medical administration, teaching and scientific research both before and after the Chinese Revolution.

PUMC also transformed the nursing profession in China. When PUMC opened, there were fewer than 300 trained nurses in the country, many of them affiliated with various missionary organizations and most of them male. Because the Chinese had never considered nursing to be an appropriate profession for women, the task of PUMC was both to train qualified women nurses and to elevate the status of the profession. Those responsibilities fell to a twenty-eight-year-old nurse from Johns Hopkins, Anna D. Wolf. She arrived in 1919 to create a training program for nurses and to organize the hospital’s nursing staff. Recruiting her initial faculty from the best U.S. nursing schools, she devised pre-nursing and nursing curricula. Within five years she established a school capable of meeting U.S. accrediting standards.Mary Brown Bullock, The Oil Prince’s Legacy (California: Stanford University Press, 2011) 58-59.

The RF’s Annual Report had been clear from the beginning about the CMB’s ambitions for PUMC: “It is the purpose and hope of the China Medical Board to co-operate with the various existing agencies in the gradual and orderly development of a system of scientific medicine in China.”The Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report 1919 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 1919) 260. (Link to PDF on Rockefeller Foundation Website) But some staff members at PUMC believed the school’s primary task was the more urgent health needs of the Chinese people.

John Grant, a professor of public health at PUMC from 1921 to 1934, sought to offer medical services beyond the campus walls. He collaborated with the city’s police in 1925 to create a public health station serving the 100,000 people living in Peking’s first ward, the neighborhood surrounding PUMC. As Grant knew, the station also provided learning opportunities for students at the university. He persuaded his faculty colleagues that PUMC students should spend a four-week rotation there.

Grant’s interest in pursuing broader public health work in rural areas found responsive allies in New York. Selskar Gunn, who had worked with the International Health Division in Eastern Europe before joining RF’s Division of the Social Sciences, traveled to China in 1931 to assess the Foundation’s work. While there he met Yan Yangchu (known to his American associates as Jimmy Yen), a pioneer in mass education and leader of the Rural Reconstruction Movement, with which Grant was already working. After several trips to China, Gunn produced a report that envisioned a coordinated program of basic education, health, and economic development.

Gunn was critical of PUMC and of RF’s and CMB’s disproportionate investment in it. By 1933 almost $37 million had been spent on an institution that would never solve China’s most pressing health problem: the severe shortage of trained medical personnel. A 1931 League of Nations Health Organization survey had concluded that China would need 50,000 physicians in order to have just one doctor per 8,000 people.

Few as they were, the cadre of professionals produced by PUMC would play important roles in shaping China’s health system. In 1946 an observer wrote to Raymond Fosdick, commenting on the small number of PUMC graduates. “Both doctors and nurses are in positions of leadership and many of them are effective in leadership…we found plenty of evidence that this small group had had an influence quite out of proportion to its size.”Letter from C. Sidney Burwell to Raymond B. Fosdick, September 4, 1946, RAC, RG1, Series 601, Box 2, Folder 15.

But many in China had expected more. A Chinese Ministry of Education assessment of PUMC in the mid-1930s urged not only that enrollment be increased but also that more classroom instruction be in Chinese. Other recommendations soon followed: increase the courses in public health, parasitology, and bacteriology; teach Chinese medical terminology; and publish papers in both Chinese and English so that they would reach a larger audience.

Henry Houghton, who had directed PUMC during its formative years in the 1920s, returned in 1934 to address these criticisms. But by the mid-1930s relations with some departments of the Chinese government had soured. Tensions between the New York office and PUMC had led to the firing of Roger Greene, and there were continuing difficulties in transforming PUMC into a more fully Chinese institution. By 1937 Houghton and his colleagues were making substantial moves toward bilingual instruction, reducing the numbers of Western faculty, and placing Chinese professors in positions of departmental leadership. Plans for a graduate medical school were also under discussion with the Ministry of Education, but the Japanese invasion in 1937 interrupted this work.

Surviving War and Revolution in China

A 1938 memorandum summarized the devastating impact of the war on medical training.

The effect of the war on Medical Education is almost incomprehensible. Only 5 of the 33 medical, pharmacy and dental colleges existing before the war continue unaffected. The remainder have either been suspended destroyed or forced to remove, in instances thousands of miles. This is an almost complete national disruption.

John Grant, 1938Memorandum from John B. Grant to Selskar Gunn, November 11, 1938, RAC, RG 1, Series 601, Box 3, Folder 26

At PUMC limited teaching continued for a time even though some prominent faculty and staff fled in 1937 to southwest China to assist with war-related training and rural health programs. The school closed completely only after the U.S. declaration of war on Japan in December 1941. The Japanese occupied the grounds of PUMC, imprisoning Houghton for the war’s duration. Heroically, the nurses moved their school in its entirety to Chengdu and reopened there in 1942.

PUMC resumed limited operations in 1947, but RF staff debated the Foundation’s role as nationalist and Communists factions fought for supremacy. Could they stay above the fray and continue their work? What was the Foundation’s role likely to be as a new political order took shape? Alan Gregg saw that Communism, which in the U.S. represented a challenge to capitalism, meant something else to the Chinese. Communism in China battled a feudal order. He concluded that this “puts American aid in combating Chinese Communism into some odd attitudes and curious commitments.”Letter from Alan Gregg to Raymond Fosdick, July 2, 1946, RAC, RG1, Series 601, Box 2, Folder 15.

In 1947, amid the uncertainty about PUMC’s future, the Foundation made a terminal grant of $10 million to the CMB. But in 1951 the People’s Republic of China nationalized PUMC and severed ties with the RF and CMB, Inc.

Between 1915 and 1951, the Rockefeller Foundation and China Medical Board, Inc. spent well over $50 million on medical initiatives in China, nearly $45 million of it to establish PUMC. Other missionary hospitals benefited from smaller Foundation contributions. Fellowships helped doctors and nurses to travel abroad for advanced training. Medical texts were translated, and medical libraries were built. PUMC is still regarded in China as an elite medical research institution. PUMC’s buildings, dedicated in 1921, still stand in the center of Beijing.

While the Rockefeller Foundation’s Division of Medical Education no longer exists, the Foundation has in recent decades supported efforts in medical education through its Transforming Health Systems program, grants for curriculum development at universities in Vietnam, Ghana, Thailand, Bangladesh and Rwanda, and a focus on programs in e-health, health informatics and health economics. Other work has aimed to increase access to equal and universal health coverage.

This post was updated in October 2020.

Further Reading

- Cheng Zhen, “A Historical Review of George Y. Char, the Pioneer of Urology in Modern China (1887-1951).” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2026.

- Howard Chiang, “The Impact of Japanese Occupation on the Peking Union Medical College.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2025.

Research This Topic in the Archives

Explore this topic by viewing records, many of which are digitized, through our online archival discovery system.

- “London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine,” 1919-1957. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, England, Series 400, General (No Program), Subseries 401.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Meharry Medical College – General Support,” 1943-1954. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, United States, Series 200, Medical Sciences, Subseries 200.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Institutes of Hygiene – Reports – Welch-Rose Report, ‘School of Public Health’,” 1915. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, United States, Series 200, Public Health Education, Subseries 200.L, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “China Medical Board – Incorporation, By-Laws,” 1915. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “China Medical Board – China Commission,” 1914. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “China Medical Board – Annual Reports,” 1917. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “China Medical Board – Peking Union Medical College – Correspondence,” 1933-1935. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “China Medical Board – Peking Union Medical College – Correspondence,” 1936-1945. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “General Education Board – General,” 1912-1921. Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller records, Rockefeller Boards, Series O, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “China Medical Board – Dissolution,” 1925-1959. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, China, Series 601, General (No Program), Subseries 601.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “China Medical Commission,” 1946-1947. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, China, Series 601, General (No Program), Subseries 601.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “China Medical Commission – Report,” 1946. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, China, Series 601, General (No Program), Subseries 601.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Commission on Medical Education,” 1935-1936. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, China, Series 601,General (No Program), Subseries 601.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Johns Hopkins University – School of Hygiene and Public Health – Minutes,” 1913-1936. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, United States, Series 200, Public Health Education, Subseries 200.L, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Johns Hopkins University – School of Hygiene and Public Health – RF DR 65, 74, 125,” 1915. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, United States, Series 200, Public Health Education, Subseries 200.L, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Institutes of Hygiene – Reports – Welch-Rose Report, ‘School of Public Health’,” 1935-1936. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, China, Series 601,General (No Program), Subseries 601.GEN, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Meharry Medical College – General Support,” 1943-1954. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects (Grants), Record Group 1, Subgroup 1.1, United States, Series 200, Medical Sciences, Subseries 200.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Peking and Its Environs [clip],” 1920. Rockefeller Foundation records, China Medical Board Records, Record Group 4, China Medical Board Audiovisual Materials, Series 4, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Johns Hopkins University – School of Medicine,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, United States, Series 200, Medical Sciences, Subseries 200.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Johns Hopkins University,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Maryland, Series 223, Public Health Education, Subseries 223.L, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Meharry Medical College – General Support,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, United States, Series 200, Medical Sciences, Subseries 200.A, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Cities/Provinces A,” circa 1905-1980. Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, China (including Manchuria, Mongolia, Tibet), Series 601, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Peking Union Medical College 1 – Album,” 1918-1950. China Medical Board records, Record Group 1, photographs, Series 1048, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Peking Union Medical College 1 – Album – Dedication Activities,” 1921 September. China Medical Board records, Record Group 1, photographs, Series 1048, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Peking Union Medical College 2 – Exteriors -Construction,” 1920. China Medical Board records, Record Group 1, photographs, Series 1048, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- “Peking Union Medical College 12 – Individuals – Staff – Hahn/Huang,” 1918-1950. China Medical Board records, Record Group 1, photographs, Series 1048, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The Rockefeller Archive Center originally published this content in 2013 as part of an online exhibit called 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (later retitled The Rockefeller Foundation. A Digital History). It was migrated to its current home on RE:source in 2022.