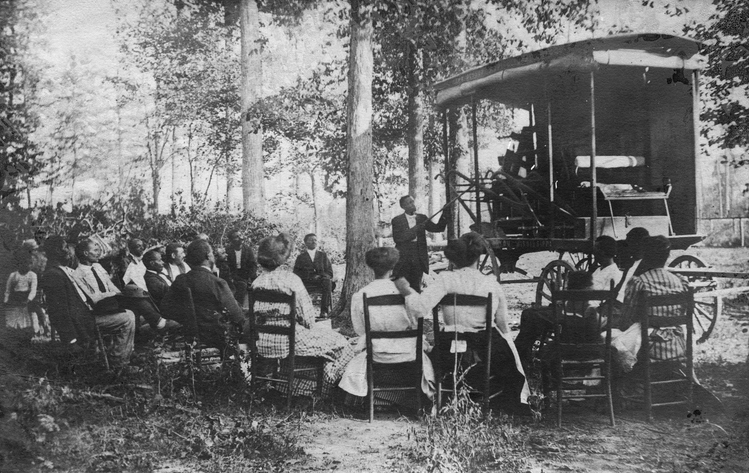

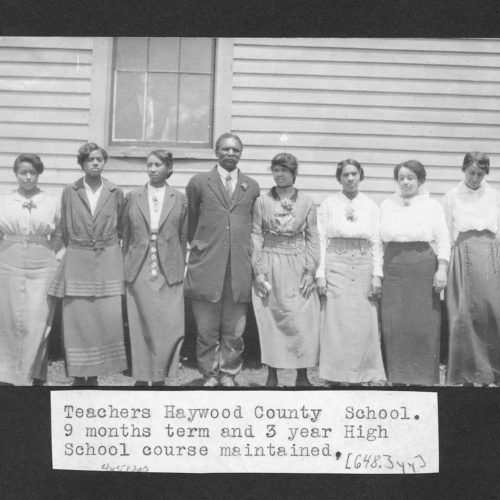

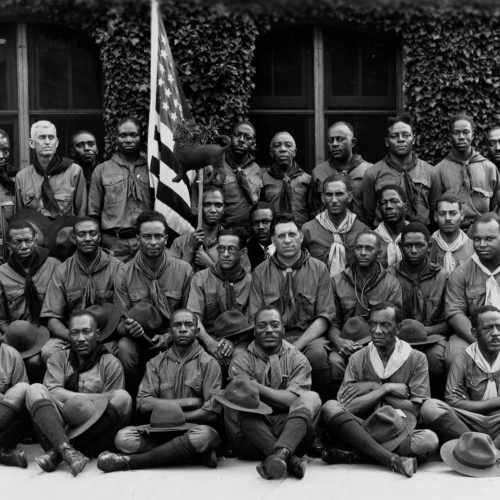

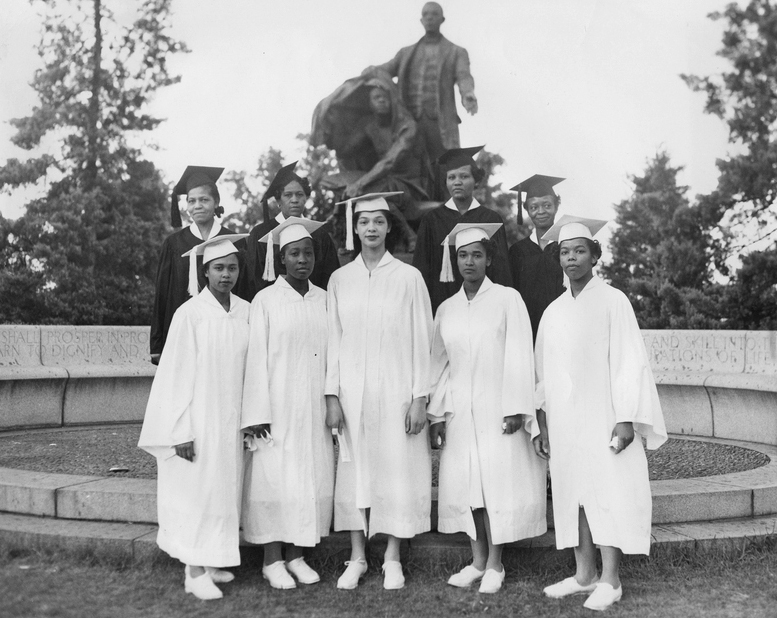

The birth of large-scale, organized philanthropy, on the heels of the American Civil War, was infused from the beginning with an awareness of racial inequality. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, wealthy individuals such as mill owner John F. Slater, philanthropist Anna T. Jeanes, department store mogul Julius Rosenwald, beauty product entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker, and oil baron John D. Rockefeller concerned themselves with Black education and economic opportunity.

The philanthropic entities these individuals established would continue to grapple with the same issues over the following decades of the mid-twentieth century.

Identifying “Access” as the Problem

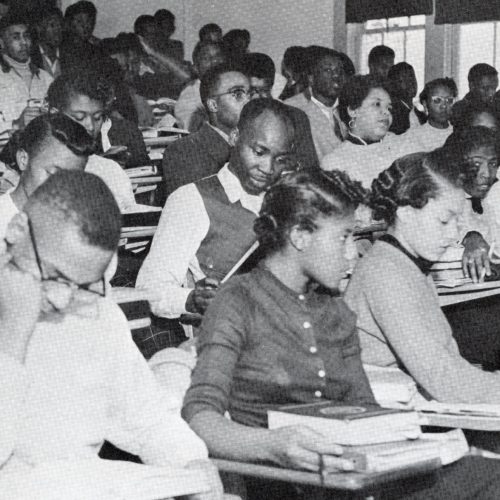

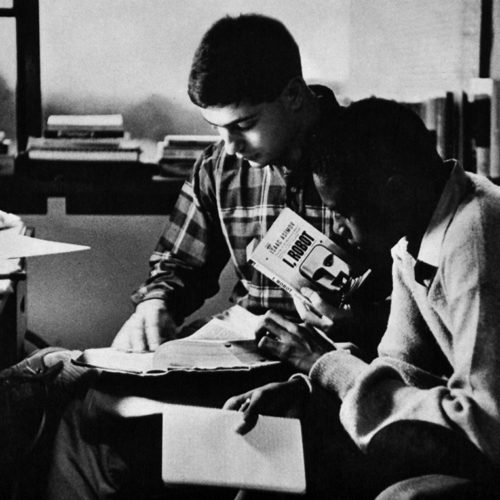

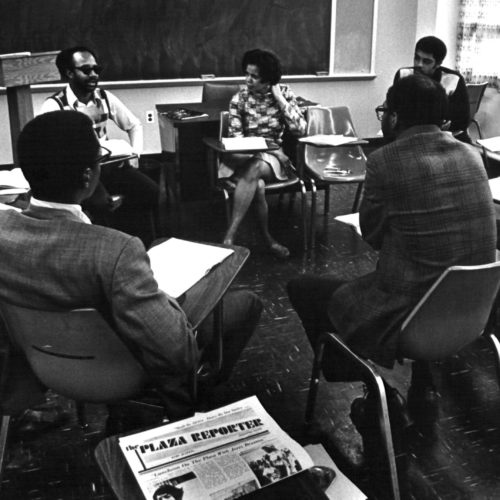

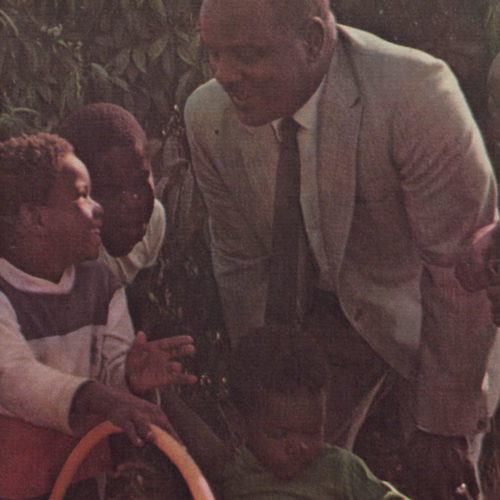

New strategies developed to target what professional foundation staff came to identify as the root cause of inequality: access.

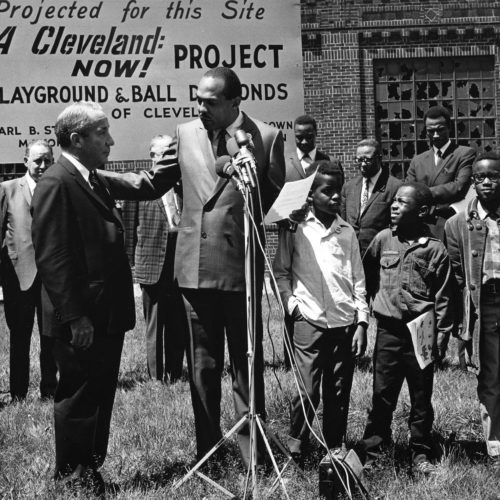

Foundations began to work in policy research and litigation, and to tackle access on a variety of levels: access to the systems and protections of the law; to education through school improvement programs and scholarships; to cultural and artistic validation through fellowships; to economic equality through investments in minority enterprise.

Replicating Power Structures

While perhaps working with good intentions, organized philanthropy’s approach to race and race relations was often plagued with problems.

Philanthropic programs undertaken within the constraints of segregation also worked to sustain the existing, unjust system. And programs aimed at reducing inequality often betrayed biases and prejudices held by foundation staff members themselves, not to mention reinforcing top-down structures of power.

Organized philanthropy’s attention to race and inequality from the start evidences, at the very least, its acknowledgment of systemic racism as perhaps the nation’s most persistent and deeply embedded problem. How to identify its causes and solutions, however, remains a challenge.

This timeline features selected episodes in a century of philanthropic engagement with race and racism, from the Reconstruction period to the Civil Rights era.